The first people I fell in love with were terrorists. The German fear of the communist Red Army Fraction (RAF) peaked in 1977, when I turned eight years old. Since then, every time I accompanied my mother to the post office, I went straight to the wanted poster next to the door and checked it for new faces. The terrorists could be anywhere, and surely we wouldn’t notice them as, of course, they would appear very different by now. But I knew they wouldn’t attack me or my parents since we weren’t rich or powerful.

The first TV news I remember were about the RAF kidnapping of Hanns Martin Schleyer, president of the Federation of German Industries and former member of the SS. I saw Schleyer with his sad puppy-dog eyes and counted the days of his kidnapping, spellbound. It was the terrorists who had made that ruthless capitalist and antisemite so heartily helpless. I didn’t want him to ever be free again. It would undo his softness and turn him again into a grim, loud man.

At school, physical violence was a thing among boys, but in the RAF, the proportion of men and women was pretty equal. These women with long straight hair and men with beards and big glasses appeared to me as perfect teachers. Their composed, waiting gazes met me from another world, and at any time they could cross mine. I dreamt of being allowed to stay with them—just me. The war on terror was the new Cowboys and Indians, and I wanted to be with the outnumbered, fearless Indians and their noble cause. Big letters at the bottom of the poster warned “Watch out, firearms!” But I knew they wouldn’t harm me, and the police couldn’t harm me either. I was too young. I counted as innocent, no matter what I would do.

Back then I had no idea that the founding members of the RAF had met during their common engagement against authoritarian suppression in juvenile shelters, part of an effort to activate fringe groups as the new revolutionary subject. Soon, in 1980, Iraq would start a war against Iran. Iran would hold against Iraq’s military supremacy with thousands of pupils sacrificing themselves as human waves which cleared minefields or drew the enemy’s fire. Mohammad Hossein Fahmideh rose to particular fame, who at age 13, in a desperate military situation, with all his comrades injured or dead, had supposedly wrapped himself in a grenade belt, pulled the pins out, and jumped underneath an Iraqi tank, killing himself, disabling the tank, and scaring off an Iraqi advance. In the Lebanese civil war, the Hezbollah, financed by Iran, revamped the suicide attack with the car bomb to attack the US embassy and the Marine Corps and make the US back out the country.

In the 1970s terrorism had been at the forefront of globalization. United by socialism, various terrorist organizations had built international networks. Bank robberies and the Cold War catered them with lots of money. They lived in multiple luxurious flats and drove faster cars than the police. The romantic illegalism of early twentieth century anarchism had evolved into a James-Bond-like parallel jet set. Your life was risky but there seemed to be a reasonable chance to stay undetected for several years and then retire undercover in a supportive socialist country. Rapidly progressing computer-based surveillance, DNA profiling, and the fall of the Wall put an end to these golden years. From then on, terrorists were best for a single strike. Trying to escape became an unnecessary waste. The suicide attack was terrorism’s desperate optimization, and children were its ideal practicians; their conception of death isn’t fully developed and they are rather easy to manipulate.

Only few terrorist suicide attacks have actually been executed by children. Using them with such cruelty has been too much of a taboo. Instead, fundamentalists have propagated suicide attacks as an act of radical manhood and orchestrated them—hyper dramatically up to the irreal—like action movies with super villains happily anticipating paradise. For leftist terrorism, the suicide attack has been less appealing, as the left can’t promise paradise. In addition, leftists have to resent the obvious divide between surviving leaders and self-sacrificing assassins. But numerous children around the world have felt inspired to commit their own suicide attacks, usually taking revenge at their most hated personal environment: their school. Diaries left behind explain their motives.

And again, these children became a main inspiration for the latest evolution of political terrorism: the lone wolf. With computer-based surveillance further evolving, even just the collective planning of a terrorist attack is likely to be detected. A successful attack has to happen out of a seemingly instant radicalization. Lone wolfs have only limited technical and logistical means. Often, they spontaneously decide about their concrete target. To compensate for their moderate immediate impact, they often publish manifestos right before the attack that are meant to inspire others to follow their example. These manifestos resemble diaries of frustrated teenagers.

The distinction between spree killers and terrorists becomes more and more delicate and politically charged. Does the terrorist agenda primarily work as a moral justification for an impulsive revenge against the next best? As transformation of a suicide into an act of martyrdom? As the PR stunt of a desperate narcissist to be finally heard?

All these interpretations don’t take the terrorist agenda seriously. They regard terrorists as mentally deranged or infantile. Terrorist threats have time and again been used by governments to declare belligerency and suspend certain civil rights. Now the anti-terrorist agenda is not only meant to protect innocent people, but also to protect potential terrorists from themselves.

While capitalism is what liberalizes autocratic regimes (at least on an economic level), anti-terrorism is what makes liberal regimes autocratic. Declaring terrorism the greatest threat to their population, well-established democracies have used the fight against it to break essential human rights like privacy, presumption of innocence, freedom of speech, and freedom of movement. Hundreds of thousands of people have been detained without trial, tortured, or killed. Governments have been secretly igniting terrorism against themselves to legitimatize further anti-terrorist measures.

With the danger of lonely wolfs, governments don’t need actual terrorism to legitimize draconic anti-terrorist measures. As soon as someone develops the intention of becoming a terrorist, it’s already too late. Anti-terrorism has to kill off the root of the problem: people’s attraction to terrorism. To imagine what this means we can look at the fight against pedophilia; an urge that is commonly condemned to the very core. Measures against terrorism might include the AI-based scanning of all digital—and eventually also non-digital—communication for dubious remarks and patterns, prophylactic medication of the jeopardized, and the ban of any media and communication that could be interpreted as a glorification of terror.

The term terrorism was originally coined to denounce governmental massacres and executions during the French Revolution. In the 1970s, the term got appropriated to denounce attacks that were meant to fight terrorist governments. Still, the use of the term seemed justified insofar as these attacks didn’t aim at an immediate coup. Rather, they were meant to frighten the government and the ruling classes to a point where they would either give up by themselves or react with draconic measures that would then provoke a proper civil war. Lone wolfs today spread terror without any specific plan. The limited impact of their attacks shows an inverse ratio to their global ambition. They would be foremost ridiculous, if anti-terrorism would have not developed a similar inverse ratio between increasing measures and further successes.

But could anti-terrorism finally become so effective that terrorism stops altogether? Or could it become far too obvious that all that keeps terrorism going is the outrageous anti-terror response? To evaluate these scenarios, we have to consider how terrorism and the definition of terrorism might evolve in the future.

Cyber Terror

The common history of terrorism starts with the Sicarii (“dragger wielder”), a splinter group of the Zealots who were fighting against the Roman occupation of Judea by attacking and kidnapping Romans and their collaborators with small daggers, concealed in their cloth. But around the same time, the first century BC, another group of terrorists was worrying the Roman empire: pirates. Marcus Tullius Cicero defined them as “communis hostis omnium” (“the common enemy of all”), which later, in the middle ages, transformed into “hostis humani generis” (“enemies of the human race”), for they are neither national criminals nor soldiers acting according the rules of a lawful battle. Disenchanted sailors, they sought revenge against the world. Samuel Bellamy (1689–1717), “Prince of the Pirates,” likened himself to Robin Hood and allegedly boasted: “I am a free prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea and an army of 100,000 men in the field.”1

Similar to terrorists in the twentieth and twenty-first century, pirates found clandestine support from regular states to complement their official politics. It was only when these states realized that they had created an uncontrollable force that most European nations would sign the Declaration of Paris (1856), which abolished privateering.

Today, it’s even more difficult to hide on the sea and its myriad shoals and islands than on land. Ships can be observed via satellite, and it’s still not possible to stay permanently under water. While at sea every nation has the right to act upon pirates, on land terrorists can find protection in a favorable state.

Cyber space promised to be the new extraterrestrial. Young, often minor hackers were the first to explore how crypto technology and self-replicating malware allows one to act anonymously, secretly, and remotely. Anonymous, the most famous cyber activist group, has for years been attacking numerous states and companies to oppose censorship and discrimination. The more AI evolves and the more the physical and the digital world entangle, the less cyberterrorism is reduced to disrupting online services and leaking information. Cyberattacks can manipulate elections or the operation of highly risky ventures like nuclear reactors, chemical plants, or airports.

Advancing robot technology (cars, drones, personal assistants, nanobots) and microchip implants might make cyber assassinations more likely than they are today, but so far, cyber terrorism hasn’t resulted in immediate murder. The most severe cyberattacks have likely been executed by nation states. How could that be changed? In 1997, crypto anarchist Jim Bell proposed an “assassination market,” where people could donate anonymously to a fund that will be given to whoever predicts the correct date of a certain person’s death—inside information that an assassinator could profit from. Alternatively, a cryptocurrency could be launched whose mined profits go to a terrorist organization. Sympathizers could offer their goods and services in exchange for this terror coin. But still, the killing has to be performed by hand.

Sea Terror

For being successful in the long run, terrorists have to please the law of the mob—attacking persons who large parts of the population detest and want to be punished. Terrorism is not just a means to a far-fetched end, but a satisfying act of revenge in itself. Sympathies are particularly huge for attacks against occupiers—as performed by the Sicarii. Contemporary terrorist organizations that assassinate common people follow a rhetoric of decolonization. Islamists attack random Westerners as imperialistic spreaders of blasphemy and consumerism; racists attack random Jews as conspiratorial rulers or random migrants as ancestors of a creeping occupation. Leftist terrorists have a more challenging agenda, as their ideology forbids them to differentiate between the value of certain lives and to kill out of revenge. This nobleness is why I, as a child, intuitively fell for the RAF.

In retrospect, however, RAF terrorists don’t appear that noble either. In need of self-defense (not of their lives, but against ending up in prison), the actions of the RAF became desperate. Still, they continued to make the rich and the powerful feel vulnerable—to the benefit of social justice. Back then, Germany’s Gini coefficient—a number measuring the degree of inequality—was one of the lowest in the Western world.

Today the ultra-wealthy more fear their own AI creations going berserk than other humans taking revenge on them for paying puny wages, bribing politicians, evading taxes, serving dictatorships, and damaging the environment. Bulletproof cars, defensive architecture, and ubiquitous surveillance have made it far more difficult to attack the rich. All the while, those who feel inclined to terrorism got lazy. Since the suicide attack frees one from the effort to escape and hide, a minimalist approach prevails: just hire a van and ram it against some strangers, or shoot around at a public square and gain a lot of attention anyhow.

Like the Russian nihilist group Narodnaya Volya that used the then-recently invented dynamite to build bombs and throw them at Tsar Alexander II in 1881, for a new wave of well targeted, awe-inspiring attacks, terrorism would have to adapt latest technology. From 1911 to 1912, the French anarchist Bande à Bonnot operated with cars and repeating rifles, which were not yet available to the French Police. Al Qaeda staged what must have been the most impressive terrorist attack so far, 9/11, by transforming jumbo jets into bombs.

After the discovery of genetic engineering in the 1970s, bioterrorism appeared as a likely new threat. Microbes and viruses could be theoretically be manipulated in ways to attack only certain parts of the population, and with the ability to self-replicate, causing millions of casualties from a single attack. Ecoterrorists could threaten to relieve nature by minimizing the human overpopulation.

But so far, there have been only few significant bioterrorist attacks—with natural agents like salmonella or anthrax and fatalities falling short of expectations. Most famously, in 1995 the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo sprayed sarin in five Tokyo subway lines. Thousands of people got injured, but only around ten died. Bioweapons are rather difficult to manufacture or acquire and difficult to target. In the future, CRISPR might make it easy to design pathogens that kill people of a certain gender or race. This is appealing to racists and sexists, but not to leftists. What could they do to spread again terror among the bigwigs, like the RAF?

The place where the ultra-wealthy make themselves most vulnerable is at sea. Superyachts allow them to travel to the most remote places without leaving a personally fitted comfort zone. Even more, some ultra-wealthy have a juvenile background in cyber privacy and dream of moving completely offshore to meet their libertarian ideals with their real lives just as with their financial assets. Still, while it’s rather easy to hide the identity of your personal devices on the internet, an Automatic Identification System (AIS) is mandatory for international voyaging passenger ships of all size. The AIS makes is easy to follow the precise paths of superyachts. They can be protected with potent non-lethal arms like sonic beams, laser beams, pain beams, security smoke, barbed wire, flare guns, and water cannons, but the moment passengers leave the vessel to swim, dive, surf or jet ski, they become easy targets. Besides, any yacht would be defenseless against a rocket attack or a limpet mine attached by a diver.

Assassinating the ultra-wealthy outside the confines of state legislation would beat them at their own game. Just as the ultra-wealthy profit from small island states that serve as tax havens, terrorists could operate from impoverished island states that allow for the uncontrolled private accumulation of weapons and explosives. To protect their arsenal from air raids, terrorists could hide it undersea. To approach the superyachts without arousing suspicion, they could disguise as indigenous fishers or artisans. The most villainous could bring children as human shields or distraction.

Stochastic Terror

Another promising terrorist strategy is to overcome the ambition of immediate killings. The success of the international operations of Al-Qaeda and ISIS was based on the interaction of a charismatic leadership and autonomous local cells. The direct communication between masterminds and executive force can also be completely cut. Rather than instructing actual terrorists, the masterminds can incite them with propaganda and instructions that are so vague that its prosecution demands a wide-ranging censorship, like how former US president Donald Trump kept his encouragements for violent uproars allegorical enough to avoid impeachment and prosecution.

More concrete incitements can be formulated anonymously and hidden in games. The author of the popular conspiracy myth QAnon stayed unknown for several years.2 Shock sites with horror stories and memes (Creepypasta) are particularly appealing to children. In 2014, two twelve-year-old American girls stabbed another twelve-year-old classmate nineteen times to become proxies of the fictional meme character Slender Man. Recent neo-Nazi networks like Atomwaffen Division or The Base propagate their cause with memes and their known followers are often minors.

Challenges that evolve over several levels and take from several weeks to several years can guide people towards gradual radicalization. Think of the lure of level cults like Scientology or Alcoholics Anonymous. In 2016, the Blue Whale online challenge made headlines—a series of fifty tasks, the last one supposedly being suicide. Alternatively, such a challenge could lead to a terror attack. To make this “riddle terror” utterly unpredictable, the challenge could automatically generate a personalized attack scenario for each participant. Or maybe only some of the participants get chosen to attack—randomly (Russian terror roulette) or according to their merits. Nobody aside from its developers would know about the parameters, just as nobody would know how many people are participating in the challenge. If you are chosen, clues could lead to logistical guidance and technical support, like weapons or explosives.

Deathbed Terror

People who commit suicide can’t be punished, but ending your own life can be hard. You can avoid this obstacle by waiting to attack until you have to die anyway. You can start your attack literally from the deathbed: your flatline ignites the bomb. As the bomb has to be installed some time ahead, it’s most secure to place it on your own property. The damage can still be significant, if your home is situated in a dense urban area or huge apartment block.

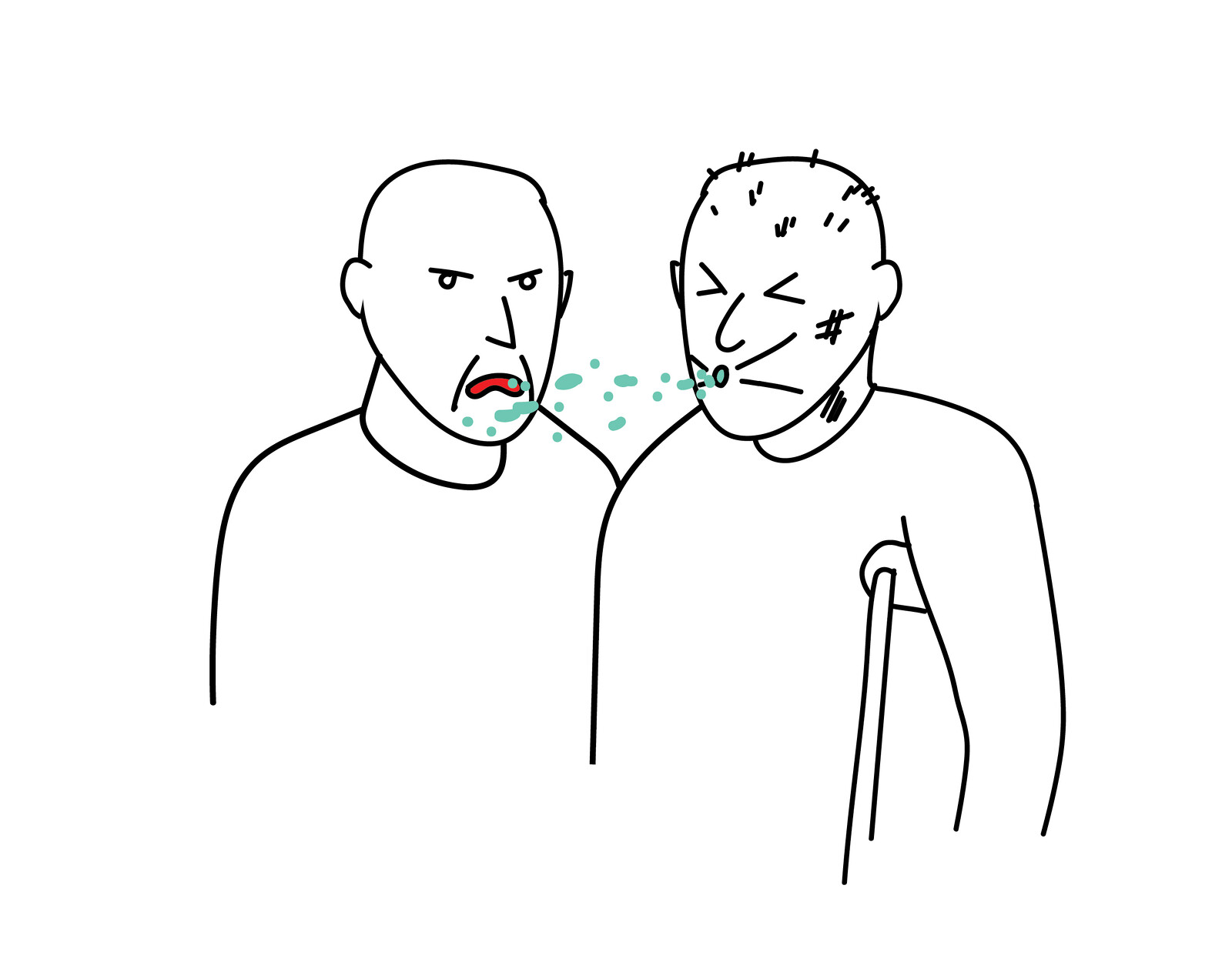

More boldly, you could start your attack some days before your supposed death. Imagine a president whose days alive are counted and who uses the state’s nuclear arsenal as a tool for extortion. Or in case you have a deadly, infectious disease, you can turn it into a slow-motion suicide attack by infecting as many people as possible, only revealing your route of terror posthumously.

If you are old and deathly-sick, most people will condemn deathbed terrorism as particularly inglorious. But if you are a child with fatal leukemia and you detonate yourself at the headquarters of the company whose pollution might be responsible for your sickness, it will break people’s hearts.

Speculative Terror

Terrorism works as its own amplifier. The deed is so outrageous that the attention it draws is far greater than its immediate harm. It is as if it happens multiple times: once in the actual physical world, but a myriad of times in the minds of the people. Terrorism is the brute prototype of mass media. Mass media copies the efficacy of terrorism without necessarily doing harm. The disruptive force of mass media is a sublimated form of terrorism (I, for one, lost my enthusiasm for terrorism and became a writer). But a terrorist attack is also the perfect feed for mass media. Mass media multiplies its force.

In 1991, Don DeLillo’s novel Mao II juxtaposed the insignificance of a secluded, alcoholic novelist and the momentousness of a Maoist terror organization. As the novelist was an elderly white male alcoholic, while the terrorists were young, vital Arabs, the book anticipated Samuel Huntington’s 1993 essay “Clash of Civilizations?” and became quite a success.

DeLillo and his readers didn’t know that since 1978, the year after the peak of the RAF, an American man had already been combining secluded writing and terrorism: the Unabomber. Ted Kaczynski lived a primitive life in the forest and sent out a total of sixteen mail bombs, killing three and injuring twenty-three, to oppose technical progress. Then, in 1995, already in his fifties, Kaczynski extorted established US newspapers to publish a book-long rant against the modern world in exchange for ending his attacks.

Kaczynski was unaware that a recent technological invention was about to make his deal unnecessary. He could have easily communicated to the whole world via the internet, and every further bombing would have added testimonial power. Children, traditionally completely excluded from publishing, understood this—leading to a steep increase in school shootings in the late 1990s.

Then came the rise of social media and a decrease in mass school shootings committed by their pupils. Adolescents didn’t need to spread terror to be heard; they could turn into bloggers, vloggers, influencers, and memers with millions of followers. In the past, it needed closed communities like tribes, churches, sects, or families to terrorize humans just with phantasms and ideas. Children were particularly subject to this indoctrination. But with social media becoming more and more immersive (live streams, HD, 3D), they themselves can turn into manipulators—subjecting other children and inspiring grown-ups.

A common terror among children is bullying: you menace and defame, also openly in front of others, to mark your superior position. Adults usually bully more discreetly to avoid retaliation. On the internet this isn’t necessary, as you can troll people who don’t know or won’t recognize you. Online rating systems enable one-click-bullying.

Even more, children can utterly enjoy teaming up against someone. When adults team up against someone, their individualism and moralism tends to blame it as unfair and scapegoating, unless that someone acted as an obvious tyrant. On the internet, however, everybody can spontaneously or systematically gang up on particular subjects without merging into a mob: sign a petition, boycott someone or something, or bet against them. It doesn’t take too much of a personal investment to bankrupt a company or even a state, install a new currency or shame a person to death.

As children are good at instantly making up stories or delving from one topic into another, their synchronizations can be highly unpredictable. On the internet, the algorithms that guide our use of search engines and social media are programmed to keep us on the consumerist track. But sudden or steered events can lead to collective actions that run out of control.

Such actions could spread terror with an explicitly anti-terrorist agenda, like going against people with certain common traits that are supposed to identify them as terrorists, warning of energy vampires that act from a distance and leave no traces, outer space terrorists who intend to kidnap our whole planet, superior beings who will punish us in or out of the future, or identifying accidents or natural disasters as clandestine terror attacks.

To contain decentralized synchronizations of agency, governments can either openly operate autocratically—through censorship and the banning of group formations and assemblies both offline and online—or gently paternalistically—making curiosity and lust for adventure unappealing unless they follow pre-designed, risk-free tracks. In the latter case, the state’s monopoly on the use of physical force is superseded by a monopoly of mental force.

Many science fictions, from Aldous Huxley’s novel Brave New World (1932) to Marco Brambilla’s film Demolition Man (1993) have given an outlook onto the shift from physical force to mental force. Usually it’s understood as new technological possibilities being abused by a powerful elite to lull the masses. But paradoxically, the post-liberal condition of today is consolidated by an expanding understanding of freedom: the more affluent, educated societies condemn as discriminating and abusive, the more unpleasant opinion and information can’t just be blamed as stirring terror, but as terror in themselves.

Stratified societies condemn unwanted remarks as blasphemy or disgrace, while post-liberal societies condemn them to protect the weak. One is about not besmirching the victors, the other about de-stigmatizing the victims. In a post-liberal world, children are the only humans who are still somewhat tolerated to go wild against others; in particular against grown-ups, as it’s they who generally dominate children.

As a child I loved the RAF terrorists exactly for not acting childish. I loved them for their sense of reality and justice, for their numerical inferiority and their cold-blooded efficiency. They didn’t make up stories or rage against the weak. In contrast, the future of terrorism is utterly childish. Whoever exerts terror will be degraded as not really grown up.

Confined Terror

Even a radically pacified human society exceeds a tremendous amount of terror, in particular against non-human beings. When it comes to nature, we are all terrorists—in the narrow sense of exerting lethal, intimidating violence. And nature is mirroring this terror back on us as global warming, storms, droughts, contaminations, plagues…

This makes any fight against human terrorism that generally suspends personal freedoms highly disproportional and anthropocentric. If we regard terrorism as childish, the obvious solution is to treat terrorists like dangerous children—not fully responsible for their actions. If they can’t be appeased with drugs, therapy, or sublimation, they can be locked up, either temporarily on their own or together with others of their kind; not to punish them but to prevent them from doing harm.

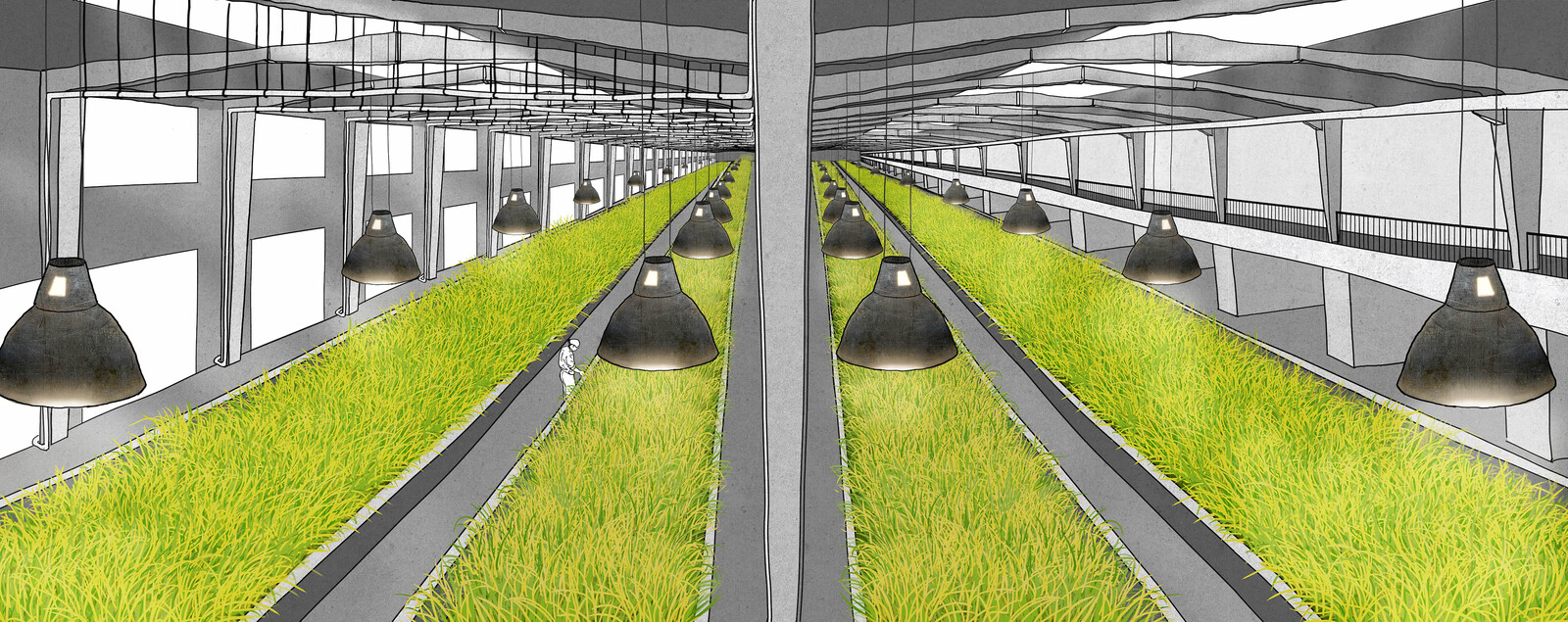

We experience this already today online, though in a privatized, erratic way: mainstream social media is cleaned up of what is considered to be hate speech, overexposure of violence or sexual obscenity, while fringe social media allows for more. This separation could be implemented with transparent and steady criteria, both online and offline. Whoever feels like speaking or acting more aggressively or having more aggressive experiences would just need to move to special zones of terror. Their harshness ranges from unlimited freedom of speech to certain forms of violence. Leaving them is possible at any time, but once you leave, you are put on probation and under special observation for a period that depends on the harshness of the zone.

Terror zones replace safe spaces. With safety being the norm, terror becomes the protected exception. Terror zones are the civilizational equivalent to wildlife reserves, protecting both: the wild life inside and the tame life outside. If animals, plants, and terrorists all count as minors, a truly diverse and inclusive society has to protect all of them as its victims and offer them an adequate habitat.

Captain Bellamy, quoted in Captain Charles Johnson, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates (London: Rivington, Lacy, and Stone, 1724).

Tom Cleary, “Paul Furber: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know,” Heavy, August 14, 2018, ➝.

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.