I have to write a story I am not entitled to tell. A parallel botanical story of myself. A story that I was made to tell.

Once upon a time, I was with a plethora of very well-known scholars and they were stepping on me. I was probably considered too young, a novice. Undergrowth. Now, I take the opportunity to tell my own story. In all honesty, I feel no pleasure in doing it. I would have loved to avoid this need. By nature, I am shy and humble. Yet, I am compelled to say the truth about myself. I repeat, I would not do it but I risk creating more embarrassment and being perceived as haughty if I do not. So, here we are. This is my story. To be precise, it is our story.

What is our story exactly? Who is this “we” in this understory? There is stem tissue, a minuscule insect, little leaves, fungi, and a myriad of tiny creatures that the human eye cannot entirely grasp. I have to admit, I am full of friends. They are that kind of diverse crew that you want to hang out with. We are messy, funny, shady, but light-hearted. I would like to think of us as a brothel.

Our brothel is an authentic one, a little sweet home; a wooden shack in the forest. Not a vulgar one, as people might describe it today, but a welcoming place, open to relationships. As much as a word might change meaning, ours is the oldest. Indeed, words travel, and in some cases, they go towards unthinkable directions, such as this one that describes us as a melting pot, an astonishing chaos of little beautiful living things.

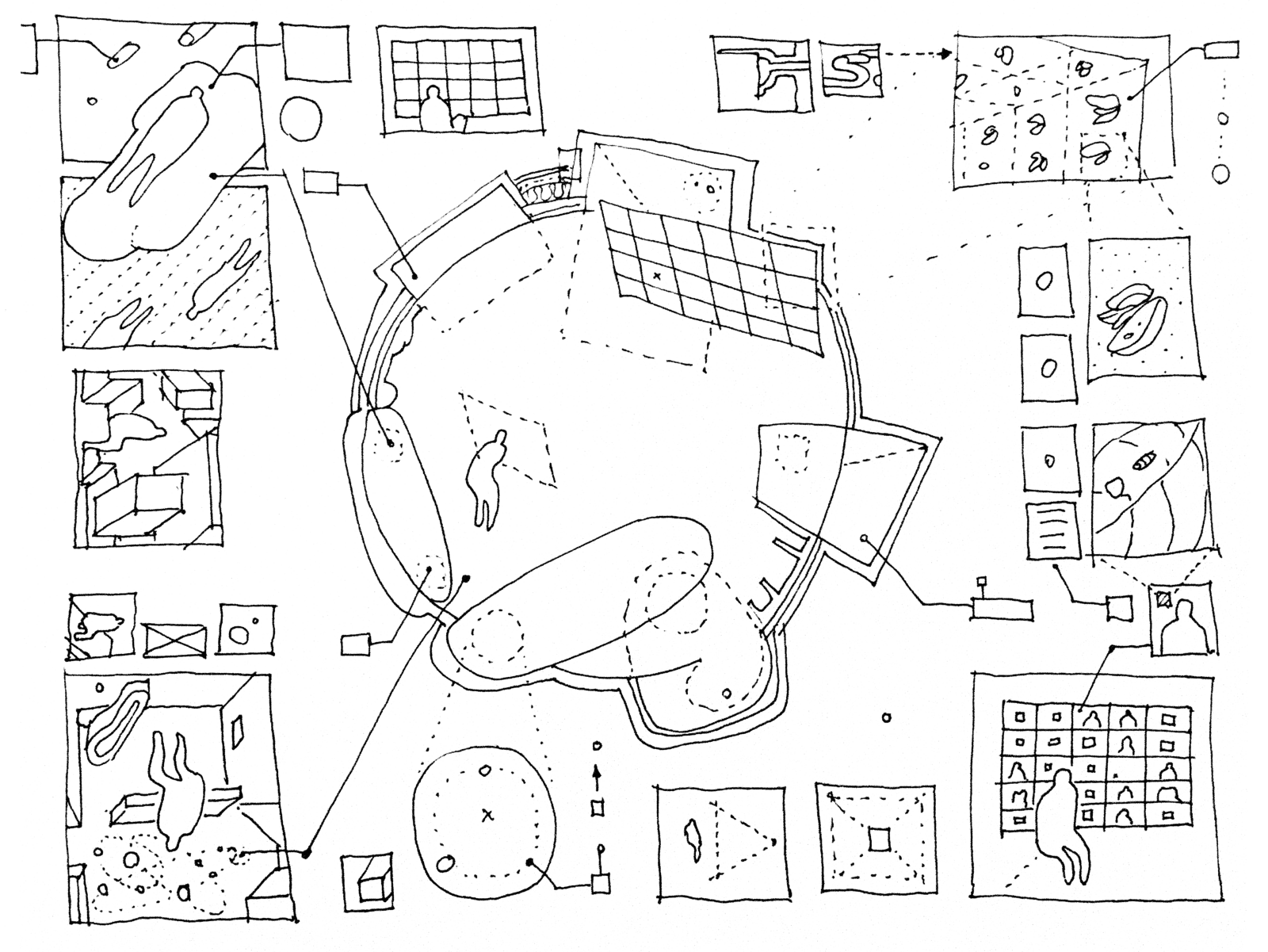

We live at the feet of our forest. If you want to consider us as a home, you can, but we are an open and variable one. We are homey as much as metamorphic. We have our own story, but beware: we are moody, changeable, and bizarre, so please do not expect a logical and consistent plot. We might be coherent, but only as a whole. We are relational, and kind of holistic; a complex complex.

Despite its vulgarization, something valuable remains in the concept of the brothel. It comes from us. It has something to do with sex and our fellows, the flowers. As one friendly scholar has written:

Flowers are very much part of our daily life: they adorn our laden tables, the living rooms of houses…They are the most welcome gifts; they are part of the most attractive wedding ceremonies. You can also find them nestled among the pages of a much-loved book, preserved, dry, almost unrecognizable. Where there is a house there is a garden, more or less large, and from the garden one expects, in the propitious season, the joyful merry bursting of the flower buds. But if the flower is nothing but a sexual organ, doesn’t all this have the appearance of an unconscious adoration, by tradition or by instinct, of sex?1

Among the little flowers are our best and sometimes precocious friends: violets, bells, primroses, periwinkle, snowdrops, anemones, columbine and goldenrod, yellow digitalis, lily of the valley, and fragrant rennet. They all grow in our shade, which we offer as a protection from winter frost.

Our behavior is more unpredictable than people may think. We are an open-ended assemblage—as they define us nowadays—that is possibly impossible to fully grasp. Our increased density, the density of the undergrowth, is now considered an indicator of forest change. But it is not sufficient to say so.

Our story reflects the overstory, the canopy, the story of our shadowy sky. It also works the other way around. Do you know how resilient we can be, the togetherness of our sky and us beneath it, the undergrowth? We continuously dance an impermanent dance. When the foliage is light and not very shady, we little ones are brighter and richer, and we have fun blooming beautifully in late spring or early summer. We are only a little bit shyer when our roof, the canopy, is thick and without gaps. But we breathe together in any case; sometimes we are more silent, and maybe a little less passionate and blooming, but we always resist. We buddy up.

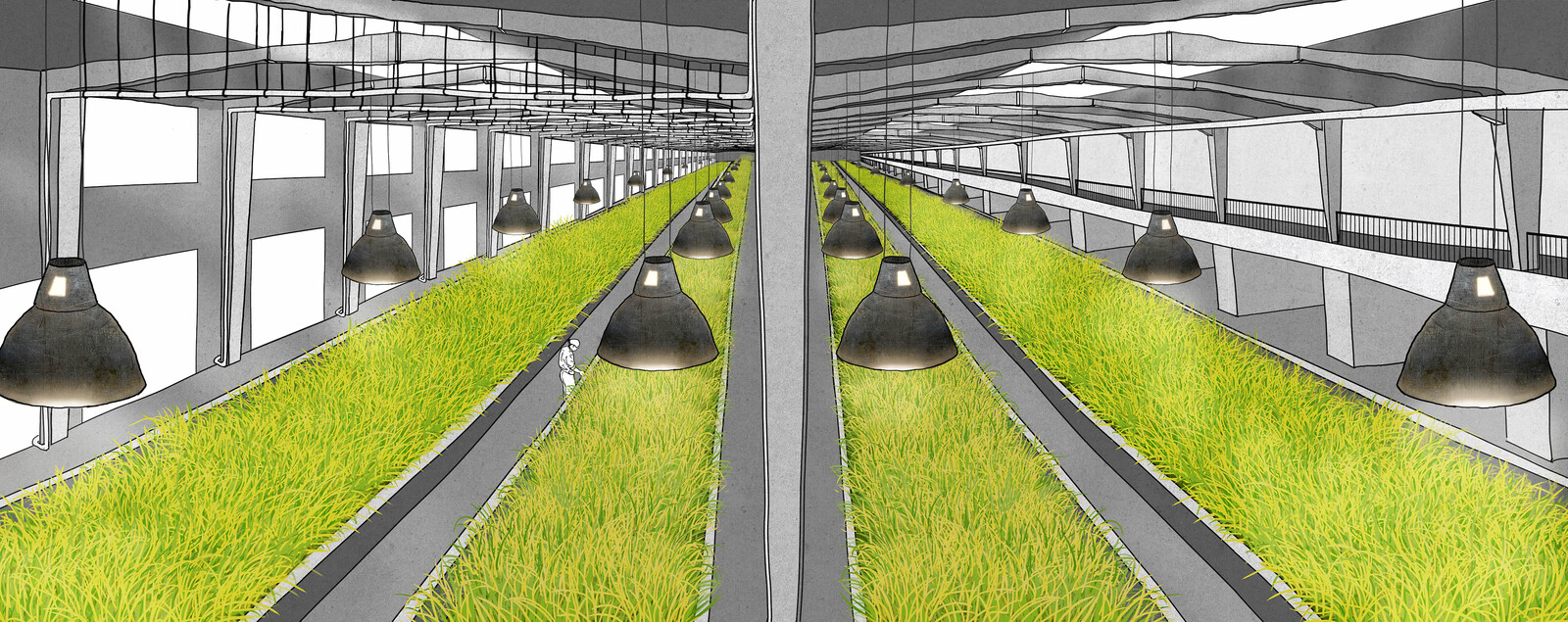

Scientists—that multitude of well-known scholars who used to step on us—come to visit us from time to time. Recently they realized that our composition and spatial organization, the diversity of undergrowth species, are quintessential indicators of the degree of naturalness of our forests. But sometimes it is much, much worse; sometimes we are simply eliminated—all of us, even the trees, our entire brothel—only to be replaced by grasslands and shrubs or agricultural crops.

This story is as old as the history of the planet, and we have seen it all. The great Julius Caesar deforested the entire Po valley brothel. Wood was one of the most essential commodities back then. It was the primary raw material for private and public buildings throughout the Roman Empire. Heating was done by wood; wood was burned to fire the bricks used in building aqueducts. Grazing by goats, sheep, cows, and pigs required deforestation too. Eventually, deforestation became a tool in warfare. Thousands of acres were cleared by Caesar to avoid the possibility of some humans running away and escaping into the forest.2

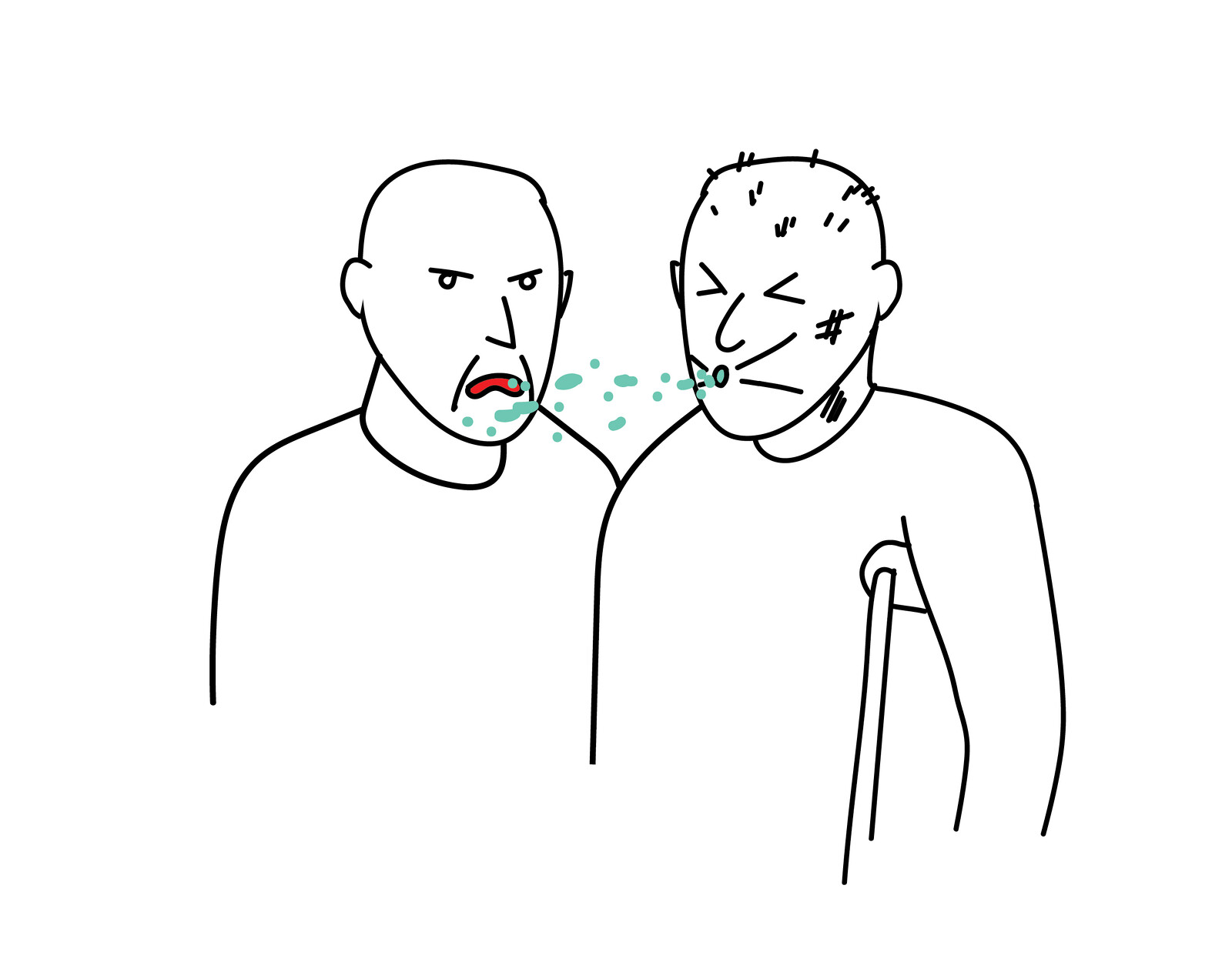

Timber is still fundamental. There is no society that does not need it. And we are happy to contribute as we can. Life is a shared breath. We know that. Human beings need us, bacteria need us too. Both may be very destructive. Living beings are not always as good and beautiful as some believe. We are not beautiful or good, nor ugly nor bad. We all hurt ourselves.

We don’t see living beings as culpable. But, of course, we all are, since the very beginning of our appearance in the world. Look at what our invisible friend, the virus, can do. Some time ago some fellow bacteria began to decimate our olive trees in many parts of the globe. Humans wanted olives and extra-virgin olive oil, but bacteria wanted a bit of their lifeblood. We are all full of desires. Sometimes we make a mess. We just find it a bit annoying when people downplay our contribution.

We limit ourselves to telling only one of our stories; a beautiful story of life and death in the undergrowth. We do it just to satisfy your desire—and ours too, we must admit—to see things for what they are: multiple, confused, contradictory, and unsolved. As we said, we prefer to stay in the shadows. But it is worthwhile for us to talk about ourselves for once, even if we are shy and a little gloomy. Then, you can understand what we are and how to walk pleasantly on us, leaving what is to be left and taking what is to be taken.

A short story of Death and Life

A tree grows indefinitely.3 A tree grows in length and thickness throughout its life. Our beloved Ficus macrophylla grows and branches out in all directions: upwards with its caulinary apexes; laterally with its branch ends; downwards with its adventitious roots, its tabular roots on the surface and its geotropically negative roots and in the soil. It is a moving sight for us little ones, to see how its enormous roots make their way between us, while its shadow grows and attracts new plants and animals.

After many years, its growth can be stopped. By “many” we mean two thousand years, five thousand years, even more. In the United States, a giant Populus tremuloides occupies an area of forty-three hectares and crosses different systems with 47,000 stems and an estimated age of over 11,000 years.

A tree seems immortal. We, the undergrowth, live and die much faster. However, we are not alone in this pluriverse. Wind, lightning, worms, bacteria, and so many other things can take out even our tallest friends. The story, however, is always much longer and more branched than one might believe. Before dying, there is life. A forest, a tree is born from tiny little things—from us.

A forest first arises from substrates with no organic matter; alluvial deposits, volcanic lavas, retreating glaciers, the accumulation of unconsolidated debris, waste of a thousand types. In the beginning there are cryptogamic species such as Bacteria, Algae, Lichens, and Bryophytes, which are then associated with herbs and shrubs.

Life comes from below. But what is below always has the sky above. For any understory there is an overstory. In the areas left by glaciers, the birth of the forest depends on blue algae, lichens, and liverworts. After ten years, vascular plants appear that are reproduced via spores with neither seeds nor flowers: our beautiful fellows, the ferns. After forty years, we are host to the flowering plants known as Dryas drummondii and the Salix. After seventy-five years, our soil becomes quite acidic. It’s not so bad, but thankfully it’s just a transition phase. And finally, after two-hundred years, a forest is born.

A forest is a patchwork, a mosaic of units in dynamic balance, in continuous movement and metamorphosis. When a forest is formed, there is no growth anymore; there are only constant changes, an incessant fluctuation. Nothing lasts forever. At some point the largest trees may fall to the ground and favor the spread of groups of young trees. Regeneration then starts, and culminates in a new spatial patchiness. In the relentless and discontinuous movement of life, young trees acquire maturity, and after maturity life goes towards death. In fact, our forest ages too.

When this process of fluctuation takes place, we see the complete cycle of the wood—from the seed germination to the development of the seedling and the tree, up to its death and demolition by all manner of plants and animals. Forests are rich in dead wood.

The multiplicity of things here becomes portentous. There may be old trees alive with parts of dead wood and cavities at the base of its trunk. There is also dead wood that stands, such as in senescent or recently dead trees. Dead wood often falls to the ground and goes through various stages of decomposition. Finally, wood can be found in the soil.

We, the undergrowth, are one with our trees. Not to mention how much we love wood. When it falls on us, it’s a feast. Think of it like the music that plays when our human companions celebrate. We all feel a part of the same life story, and a new cycle begins. And I’m sure you wouldn’t like it either if they cut your music off while you’re having a lot of fun. Please do not deprive us of our dead wood. It gives us joy, life!

Recycling dead wood is the, let’s say, “mortal” phase of forest dynamics. Here, we in the brothel are one with the trees, and vegetal and fungal diversity is just as important as it is when the forest is growing. Not to mention the role that our little friends from the animal kingdom have in this phase. A whole ensemble of rodents, bryophytes, bats, birds, and insects; stag beetles, oak beetles, hermit beetles, collared flycatchers, three-toed woodpeckers, noctules. Deadwood stores a huge energetic mass and nutrients, initiating new segments of the food chain, including scavenging micro-organisms.

As in an endless cycle, our cooperative work returns to the tree, regenerating it. Life, death, new life. We are food for each other. And we regenerate. Even the least treated waste can sometimes be surprising. When we heard that our comrades from Costa Rica were reborn from tons of oranges thrown there on the ground, we burst into tears of joy.4 They had lost all hope. They felt more and more alone, but at a certain point, with a few decades of patience, all their friends returned, the party started again.

It is not even known how this could have happened. But all those who were found guilty of polluting this area became, counter-intuitively, regenerators of the tropical forest. Life is strange. Let’s think about the present and invent queer projects for the future. The past is always rotten.

***

Our story ends here, and we can only tell you what we see. But what we feel is even deeper, penetrating the bowels of the earth. We are rich in mushrooms. Everyone knows this; mushrooms are very famous. But they are proof of the fact that everything contains multiplicity; some are delicious, others are poisonous. Mushrooms are the visible form of a very long history, but you would not think that if you were to see how quickly they sprout following a good rain.

We think the forest should simply be called wood. We have heard botanists, for example, say that a forest is only a virgin, uncontaminated one; in short, one that does not exist. We have always been contaminated, but we exist, we cooperate, we create. We dance at the edge of the world. If there is a nature, one deserving of this name, it should be whatever manages to live despite capitalism.

Call us nature. Call us life, or call us living beings. The tree of life is a patchwork. Are viruses living beings or not? Are they parasites? Are they sufficiently dangerous to reach a place in the tree of life? We don’t know. We contaminate ourselves. We collaborate. We are also in conflict.

History always moves in circles. We say things that others before us have said. Because we collaborate, we think together. Above us we recognize only the trees. They are old and have seen it all. They survive for millennia and almost do not know death. And if they know it, now we can say it loudly, how much more life they can create. What humans call God we call trees.

Elio Baldacci, Vita privata delle piante (Milan: Bompiani, 1944), 12–13. Author’s translation.

See “The Role of Deforestation in the Fall of Rome,” The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: Earth Edition, March 23, 2004, ➝.

The story is inspired by Francesco Pedrotti, “Lectio magistralis,” Università di Palermo, November 28, 2006; and Daniel Vallauri, “Dead wood, a gap in French managed forests,” Dead wood: A key to biodiversity, May 29–31, 2003, Mantova, ➝.

Jonathan J. Choi et al., “Organic Wastes and Tropical Forest Restoration,” Tropical Conservation Science 11 (2018): 1–5, ➝.

Cascades is a collaboration between MAAT - Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology and e-flux Architecture.