Many contemporary videogames are inherently architectural, dealing with the depiction of constructed space and actions that take place within it. Beyond often-referenced titles like Minecraft (2009), SimCity (1989), or Cities: Skylines (2015), architectural space regularly operates as both backdrop and protagonist. One of the most recent gaming phenomena, Fortnite (2017)—ostensibly a “last player standing” shooter game—has players recycling building materials with a giant pickaxe and rapidly fabricating structures in the landscape to hide themselves or access new areas while holding architectural blueprints in their hands. Players become commandos-cum-architects where the rapid and precise building of enclosure is as potent a weapon as the crosshairs of the virtual gun. No Man’s Sky (2016) has pushed the boundaries of “procedural” systems, where unique game worlds and the architecture that resides within it are assembled through an algorithm. The generative meets the narrative and symbolic in Dead Cells (2017), with themed areas (biomes), the constituent spaces of which are assembled randomly each playthrough.

Despite this architectural potential, games as entertainment media have no prerogative to solve spatial or social issues. This can produce deviant, unprecedented, and explosive ways of structuring space. While having been adopted as a tool for architectural and social engagement, Minecraft’s popularity grew based on a gravity-free, near-infinite environment with its own complex fictional material economy. Videogames foreground fantastical environments because they are entertainment media that are designed to draw players into imagined and novel systems. Yet in doing so, they reestablish the importance of utopian, synthetic world-building practices that first revolutionized the architectural discipline in the 1960s and 70s. Games remind us of the historical moments when utopic architecture held a mirror up to society. But crucially, as a medium they also provide the platform for architects to extend such practices into the future.

Modern game engines can import geometry from most architectural 3D modelling packages, yet currently they are mainly used by architects to depict built works in virtual reality, placing clients within a building before its completion. While this is a development in architectural image-making, it does not take full advantage of the conceptual and structural possibilities the videogame offers.

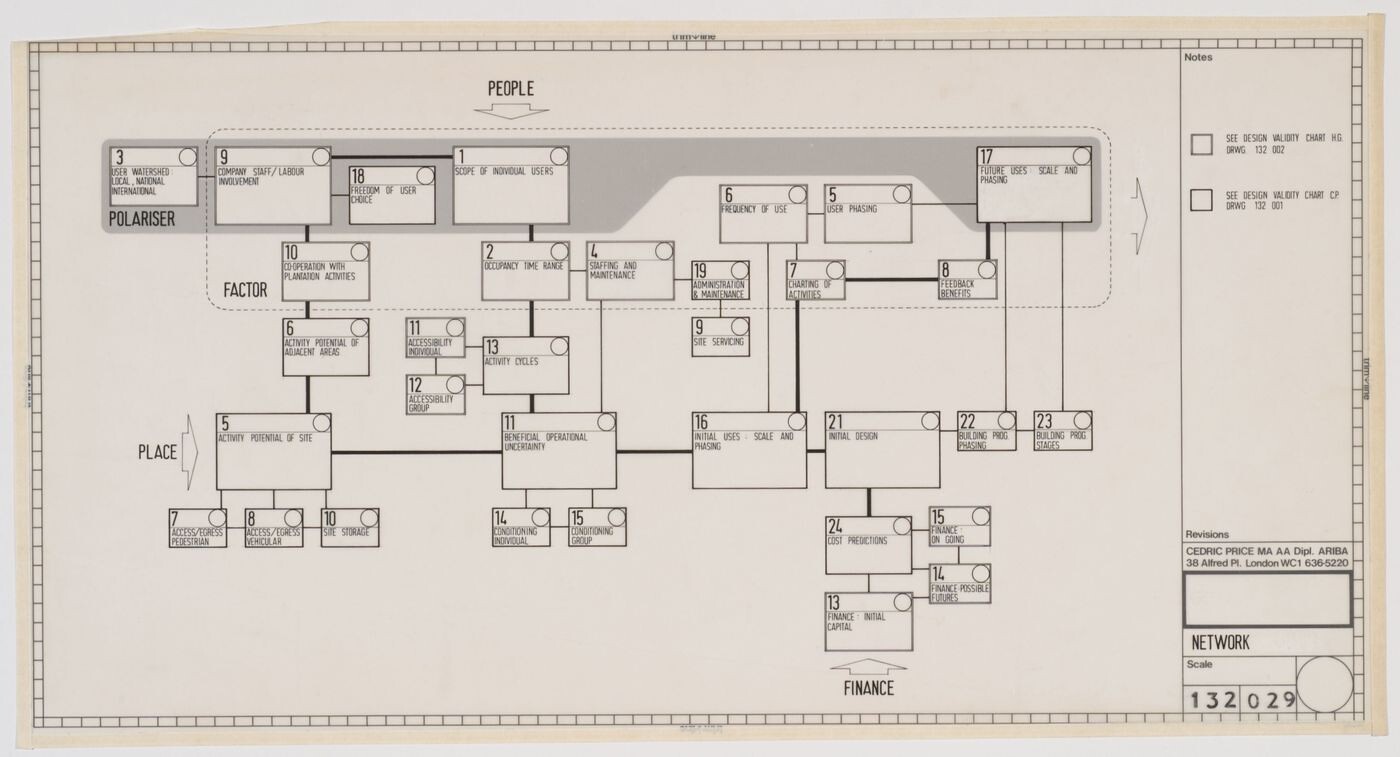

Cedric Price, Generator project, White Oak Plantation, Yulee Florida: initial design network showing three starting points, 1976–1979. Black ink and masking tape on paper with xerographic copy and pieces of self-adhesive plastic film on verso. Source: Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal © CCA.

%20Architecture.jpg,1600)

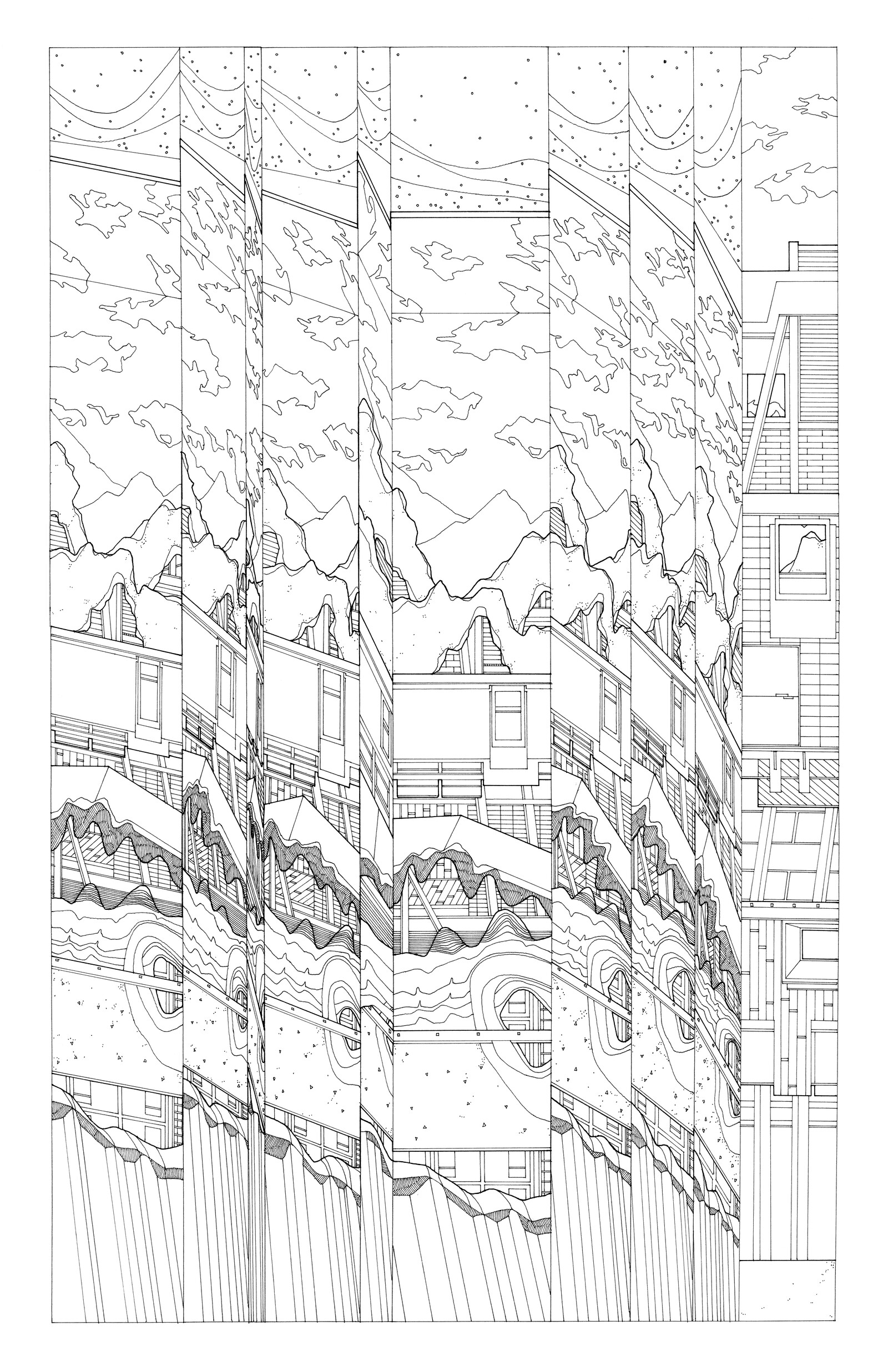

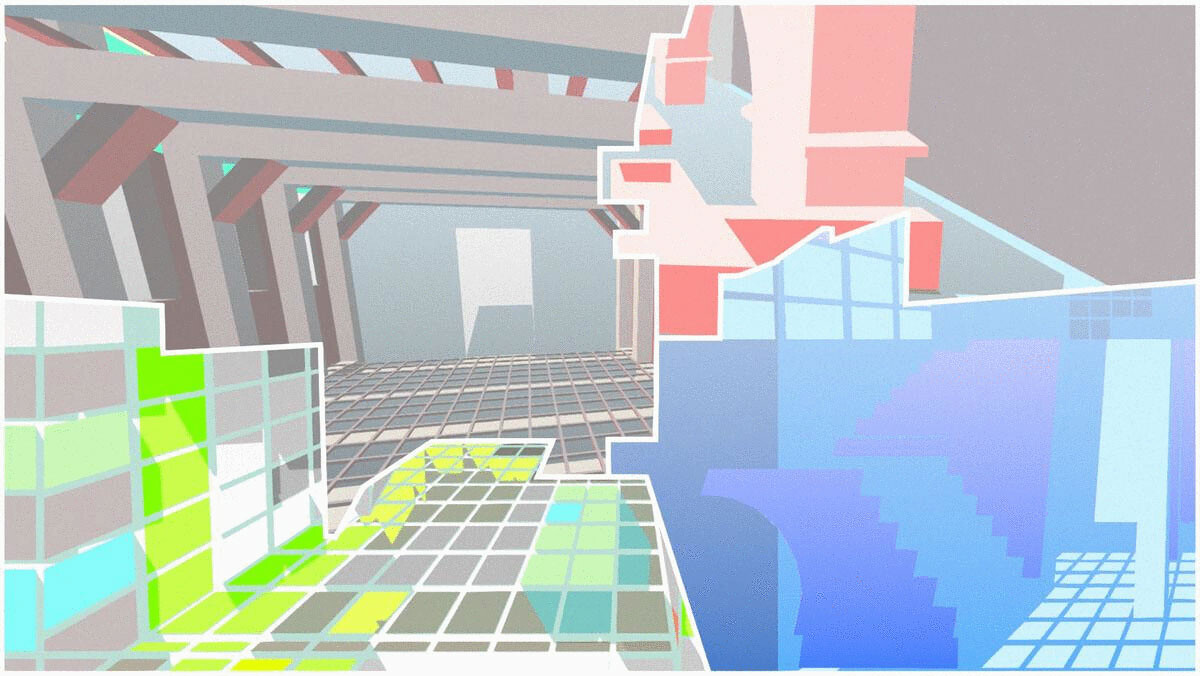

In Arkane Studios’ Dishonored (2012), moral decisions by the player (called Chaos) affect the formal properties of the virtual city of Dunwall. Luke Caspar Pearson, Advertisements for (Game) Architecture, digital collage, 2017.

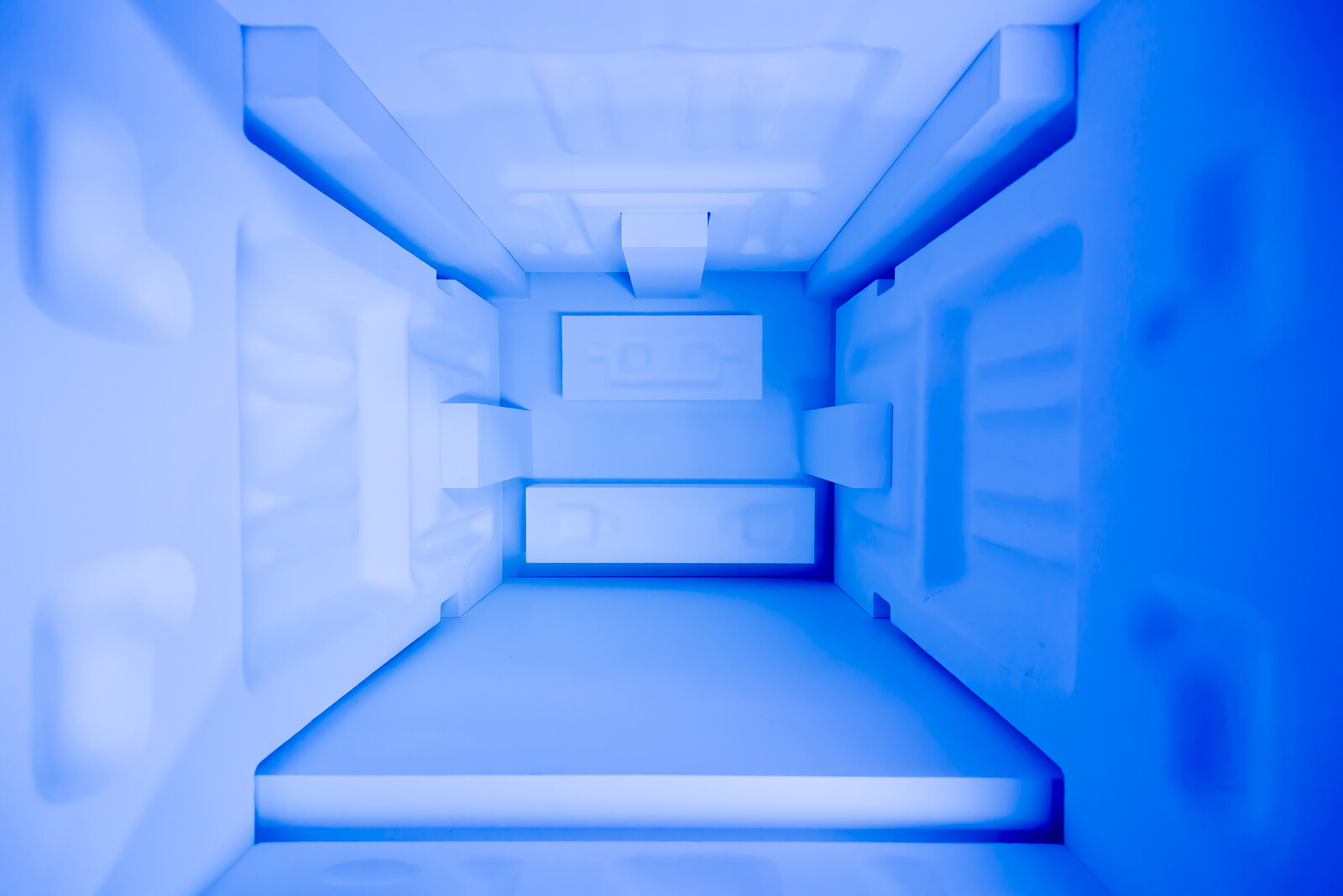

Taken from a series of screenshots made using cheat codes, Noclip World: Hall of Mirrors (2013) exposes the contingencies of game worlds once the player breaks their boundaries.

Cedric Price, Generator project, White Oak Plantation, Yulee Florida: initial design network showing three starting points, 1976–1979. Black ink and masking tape on paper with xerographic copy and pieces of self-adhesive plastic film on verso. Source: Cedric Price fonds, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal © CCA.

Worlds for Action

One definition of this structure is McKenzie Wark’s argument that games provide “worlds as if they were not just for you to look at but for you to act upon in a way that is given,” suggesting that action and its design must be incorporated into realizing architecture through videogames.1 Such a situation recalls Bernard Tschumi’s declaration that “there is no architecture without action, no architecture without events.”2 In a game world, everything is defined by actions—a wall or rock must be encoded such that the player may bounce off them. Materiality is constituted through the event. If Cedric Price’s Generator Project (1976–1980) proposed an architecture incorporated with intelligent computerized systems that would respond to the actions of users, then a virtual city like Dishonored’s Dunwall (2012) takes this to a global scale. Depending on the player’s actions, Dunwall’s weather systems, routes through levels, and social interactions change, producing an objectively different environment responding to one’s subjective actions within it.

Price explored the integration of dynamic systems into architecture through organizational diagrams. However, videogames add a thick and disorientating crust of symbolism and pop-culture on top of the systems regulating space. Michael Nitsche describes game space as a layered condition, running from coded workings of the machine through to the social space in which games are played.3 The design of architectural worlds through layers of representation, rules, and events resonates most clearly with the generation of architects preceding Tschumi’s event-architecture and working at a similar time to Price. Their work explored architecture as a project through multiple concurrent strands and tackled the rise of consumerist technoculture, of which games have become a flagship medium. By their nature game spaces involve sequences of user-instigated events and systemic reactions taking place in synthetic worlds, yet such relations already concerned of many of the twentieth century’s most experimental architects.

One crucial similarity between our current, highly-gamified society and avant-garde architectural projects of the past was an emphasis on civic playfulness and leisure. Price, Yona Friedman, and Archigram all proposed giant mobile infrastructures that could accommodate the mores of users. In The Planet as Festival (1972–1973), Ettore Sottsass developed a trippy collection of drawings for a post-work society exploring the depths of human pleasure. The Italian radicals such as Superstudio and Archizoom designed mobile systems, reconfigurable cities, and ran nightclubs. At Expo 70, Arata Isozaki designed several anthropomorphic robots that operated as characters under Kenzo Tange’s space frame. Nowhere was such a desire to enmesh the logics of play and architecture together so clear as in Constant’s New Babylon (1956–1974). Constant named the citizen of his new city as “homo ludens” (man at play), not coincidentally the title of Johan Huizinga’s seminal text on games and game playing. New Babylon represented an architecture where “there is only the playful drifting through an infinite and endlessly manipulable interior space.”4

Constant foresaw developments in construction technologies as being key to the realization of New Babylon, arguing “technologies have developed to such an extent that construction methods represent virtually no further obstacle at all to the realization of very free forms, involving an absolutely original conception of space.”5 If this prophecy was not realized in physical form, the development of game engine software has provided an alternative, virtual, means for this type of spatial expression. In this sense, it follows closely to Marie-Ange Brayer’s argument that “New Babylon is therefore a ‘dynamic labyrinth’ … the forerunner of our globalized and dematerialized society, a purely informational system.”6 Through projects examining the encapsulated nature of game space, from the work of artists such as Harun Farocki (Parallel I–IV, 2012–2014), JODI (Max Payne CHEATS ONLY, 2006), and in my own Noclip World drawing research (2013–2014), we can see that many game worlds have this cultivated “interiority” that places the player within a virtual world set by manipulable systems that are similar to Constant’s predictions, just by other means.

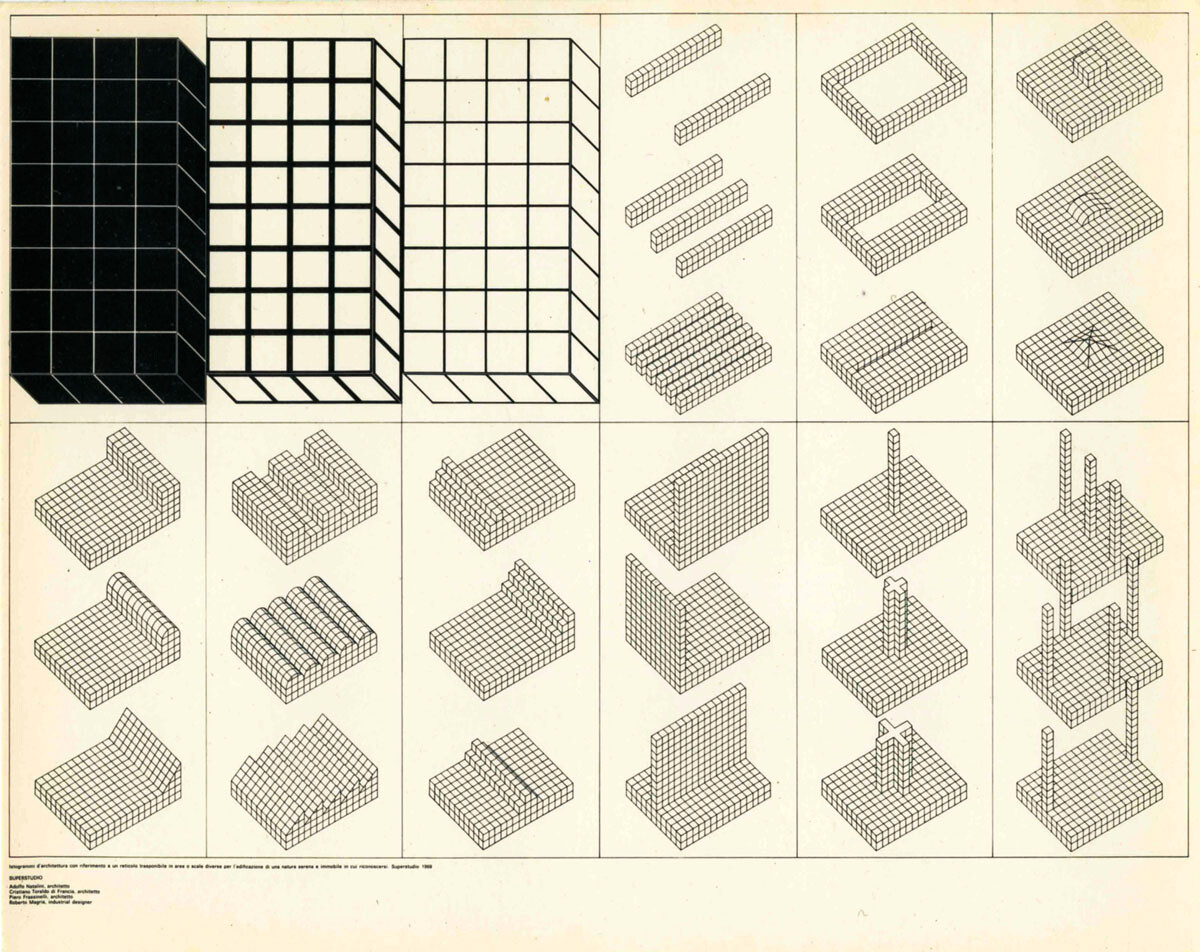

Superstudio, Catalogo degli Istogrammi d’Architettura, 1969. Source: BMIAA © Fondo Superstudio.

Archizoom, No-Stop City, Parcheggio residenziale Sistema Universale, paesaggi interni, 1969-1972. Parma, CSAC, Universita di Parma. Source: Detail Online.

The arcade game cabinet of Midway’s 1972 Dune Buggy uses a Pepper’s Ghost visual technique to combine reflected landscapes with physical mechanisms, in a strikingly similar way to Archizoom’s model cabinets.

Superstudio, Catalogo degli Istogrammi d’Architettura, 1969. Source: BMIAA © Fondo Superstudio.

Playing with Utopia

The above noted radical architects, particularly the Italian avant-garde, foregrounded the relationship between cutting-edge technology and leisure which games continue forward. Digital discourse in architecture is increasingly focused on the “utility” of computation in fabrication, machine learning, or blockchain technologies, but games re-energize conversations on play and leisure in society. As such, to see games as “follies” or simply entertainment is not necessarily a deficit of the medium. In their playful utopic nature, videogames are echoes of historical architecture projects that moved beyond buildings into conceptual fields, redefining what we could consider to be architecture. Such projects combined experiments in representation, utopic world-building, and countercultural thinking to create seminal works which still resonate today. As Pino Brugellis and Manuel Orazi argue:

Some of the same authors defined their works as “negative utopias” in so far as they staged urban palimpsests aimed at monitoring and warning of the impending alienation of man, consumerization, the normalization of thinking, a world that was entirely equal and repeatable, cold, smooth, without emotion. The strength of those works lies precisely in their unabashed staging of the contradictions of those years, which are unfortunately the conflicts and contradictions of the present time and perhaps of the near future.7

Beneath the (negative) utopian surfaces of the representations produced by Superstudio and Archizoom sat intellectual and organizational systems that bound each group’s work together. Superstudio’s project, for example, ran from subversive perspective drawings, to furniture pieces, narrative-driven utopic stories (Twelve Cautionary Tales for Christmas, 1971), and their histogram system of compositional objects. Their “negative utopias,” which held a mirror up to architecture and society, were derived from work that enmeshed “high” and “low” culture into a new form of spatial practice. While most famous for their perspectival collages (such as The Continuous Monument, 1969 and Supersurface, 1972), we can argue that Superstudio’s most notable work was that underlying structure from which all these projects emerged: a diverse set of studies and experiments that tied together in the process of redefining an architectural practice.

This is perhaps even more overt in Archizoom’s work. Their No-Stop City (1969) models in mirrored boxes (techniques used in arcade games of the time such as Dune Buggy, 1972 by Midway), instantiate a form of virtual space unfolding when viewed from the correct angle. We can see this as a prescient prediction of virtual worlds to come, when, as Francesca Balena Arista argues: “for Archizoom, the height of their technology would instead be invisible technology, that is, electronics.”8 In their negative utopia, the lateral spread of the world would become a condition whereby, in Archizoom’s Andrea Branzi’s words, “the city no longer ‘represents’ the system, but becomes the system itself, programmed and isotropic.”9 Given that projects like No-Stop City and The Continuous Monument were literally isotropic—visually and ontologically expanding in all directions through the grid—we might question how closely the often chaotic and confusing worlds of games bear to these idealized systems and abstract grids. However, the power of games emerges from the grid and organization system being utterly intrinsic yet not so obviously foregrounded. Game code should feel naturalistic and retreat from view while simultaneously regulating everything in the world. New forms of spatial arrangement emerge that are particular to games and offer new possibilities for radical architecture to engage with the isotropic. Take even an infinite runner game—commonly played on mobile devices—where the player moves ever-forward through a repeating world, usually seen in one-point perspective. Here the isotropic grid defines points that literally allow architecture to rebuild itself forever along a singular trajectory.

Invisible Isotropics

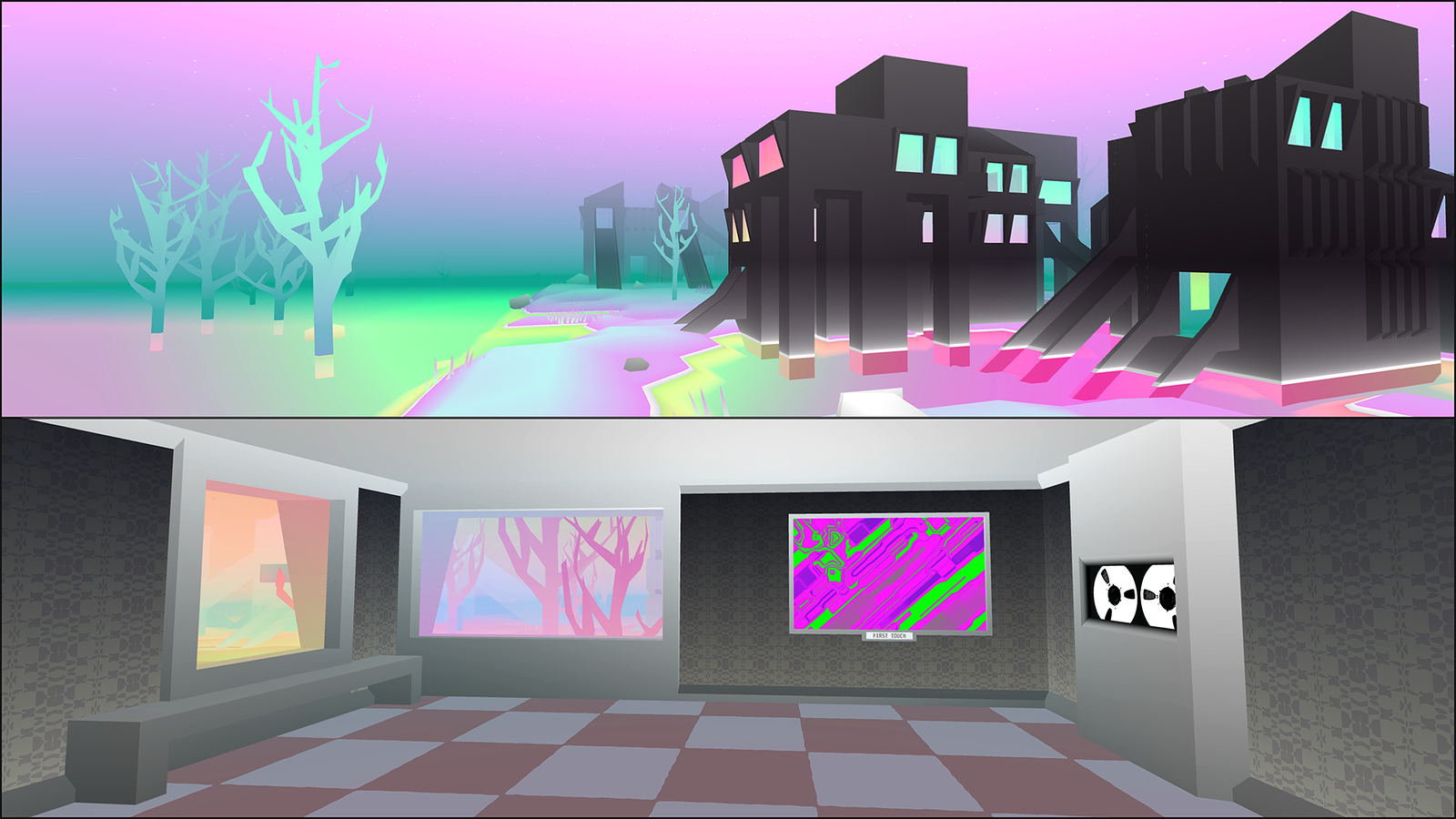

An isotropic system is also clearly present in the voxel-based volumetric grid of Minecraft. Yet looking beyond the surface of most other games and into their engines, every object within their worlds are typically defined in relation to a (near-infinite) Cartesian grid. Movement, gravity, and momentum are all numerically defined in relation to the isotropic. Even the rendering of materials and light simulation are calculated in such a way. What Archizoom’s work ultimately foreshadowed was virtual zones of unprecedented visual and protocological complexity that are held together through these organizational systems. These systems are often beneath the surface, holding the world together, but with patterns to be intuited by the player. However, the ability to position and calculate anything within the isotropic world also lends itself to systems that use the real-time computation of the game engine to synthesize architectural space through algorithms. Here again we see the protocological come to the fore. This is particularly relevant to procedural world building, such as the work of anonymous developer Strangethink. In their game Secret Habitat (2014), a series of procedurally generated art galleries are inhabited by artworks which have also been generated by a coded system. Secret Habitat’s world becomes a utopic manifestation of radical shifts in the production, dissemination, and communication of imagery caused by digital technologies, an architecture where the institution and the artwork are derived from the same algorithm. Such generative systems are also used in plan—like Archizoom—in the tactics game Frozen Synapse 2 (2018) where procedural generation is used to generate building floorplans in a citywide network of spaces given over to tracking, movement vectors, and sightlines.

The game world of Mode 7’s Frozen Synapse 2 (2018) is comprised of buildings, the floor plans of which are procedurally generated to vary with each playthrough.

What is placed into these isotropically regulated fields is, in fact, the type of three-dimensional geometry that architects regularly produce with digital tools. As Lev Manovich argues, new media build upon prior media forms, and extend them through technology.10 For Manovich, navigable virtual spaces were a medium utterly impossible before computation, but they connect visual arts culture and computer science into one spatial system.11 Games are not tied to one prior medium but instead combine many. Superficially they can present worlds through protocols of architectural drawing or camera optics—the ubiquitous isometric or first-person viewpoints. But prior media are more deeply entrenched. Games are synthesized using 3D modelling software, 2D graphics, written narratives, and various levels of coding—from material behavior to control systems, physics, and artificial intelligence protocols. Once built, game spaces become closed, utopic systems—a separated space manifest as and when the user runs the program.

From the Utopian to the Atopian

One of Louis Marin’s structural descriptions of utopia bears a close resemblance to the formal composition of game spaces: “Utopia is thus the product of a process by which a specific system complete with spatial and temporal coordinates is changed into another system with its own coordinates, structures, and grammatical rules.”12 Such a systemic transferal recalls Ian Bogost’s exploration of games as “the rule‐based representation of a source system” and, taken to its extension, a “caricature” of real systems.13 Such a structure reinforces the links between videogame space and conceptual architectural projects. It is both literally and metaphorically Branzi’s isotropic system. This is not to say that we can consider every videogame to be a work of conceptual architecture, but that their formal properties lend themselves towards exploratory architectural practice.

For Wark however, game spaces should not be considered utopian but atopian. Wark argues that “if Utopia thrives as an architecture of qualitative description, and brackets off quantitative relation, atopia renders all descriptions arbitrary. All that matters is the quantitative relations.”14 By way of example he discusses Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (2002), arguing that a game superficially about transgressive behavior is actually about the player engaging with a set of rules. Playing GTA supports this view, given that systems for traversing the world trivialize certain actions (one button press to steal, enter, or exit a car), turning every vehicle into a resource for mobility within that world. For Wark, games function as the world’s “atopian shadow, in a parallel to the way that the very positivity of a utopia acts as a negation of the world outside its bounds.”15 However, we can see that such worlds had already been predicted by architects. Branzi had already foreseen these atopian realms when he argued “nowadays the only possible utopia is quantitative,” which suggests he saw the imaginary, conceptual city as bearing close to the logics of electronic systems.16

In GTA’s case the player is involved within these atopic systems while also witnessing a representational space on the screen that ties itself close to reality. Cars and the city look real, even if the actions that support free movement are highly systematic, suggesting an extension of Archizoom’s quantitative utopia. Of course, Grand Theft Auto represents the type of hyper-commercialized juggernaut that Archizoom would have surely stood in opposition to. Yet the agency of the videogame world could surely be applied towards Branzi’s key motives for the group’s work: “that of understanding the objective laws which control the shaping of the urban-architectural phenomenon, demystifying the complex ideology which surrounds the discussion and conditions the form it takes.”17 If Reyner Banham’s writings were instrumental in bringing Los Angeles to attention as an automobile-structured architectural landscape worthy of interest, Rockstar, the makers of GTA, encode the very nature of a utopian city of movement and transgression into systems which emphasize this through being within the world. As the tools for architects to realize game spaces are widely available, the possibility to co-opt these structures for our own means becomes increasingly clear.

By instantiating hermetic worlds, manipulated through controller, screen, and coded protocol, videogame worlds resonate with the idea of architectural utopia. Wark argues that “if in utopia everything is subordinated to a rigorous description, a marking of space with signs, in atopia nothing matters but the transitive relations between variables.”18 Yet within game worlds this seems somewhere in-between. While a videogame environment is ultimately algorithmic, many designers go to great pains to produce “rigorous descriptions,” and videogame aesthetics certainly privilege the presence of signs in terms of delineating their worlds and meanings. The qualities of these environments as synthetic places, with attendant stories and “history” (commonly known as “lore”), is part of what brings people to these worlds.

Zhibei Li, Shenghan Wu, and Meiwen Zhang (Videogame Urbanism Studio, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL), Playable Planning Notice, 2017, gameplay footage. This game exploits the looseness of language used in British planning notices, allowing players to prototype alternative structures that would also satisfy the vague language used to communicate to the public.

In You+Pea’s 2018 videogame Projectives, four players work together to recreate on of Vredeman de Vries’ perspective studies through multiple viewpoints.

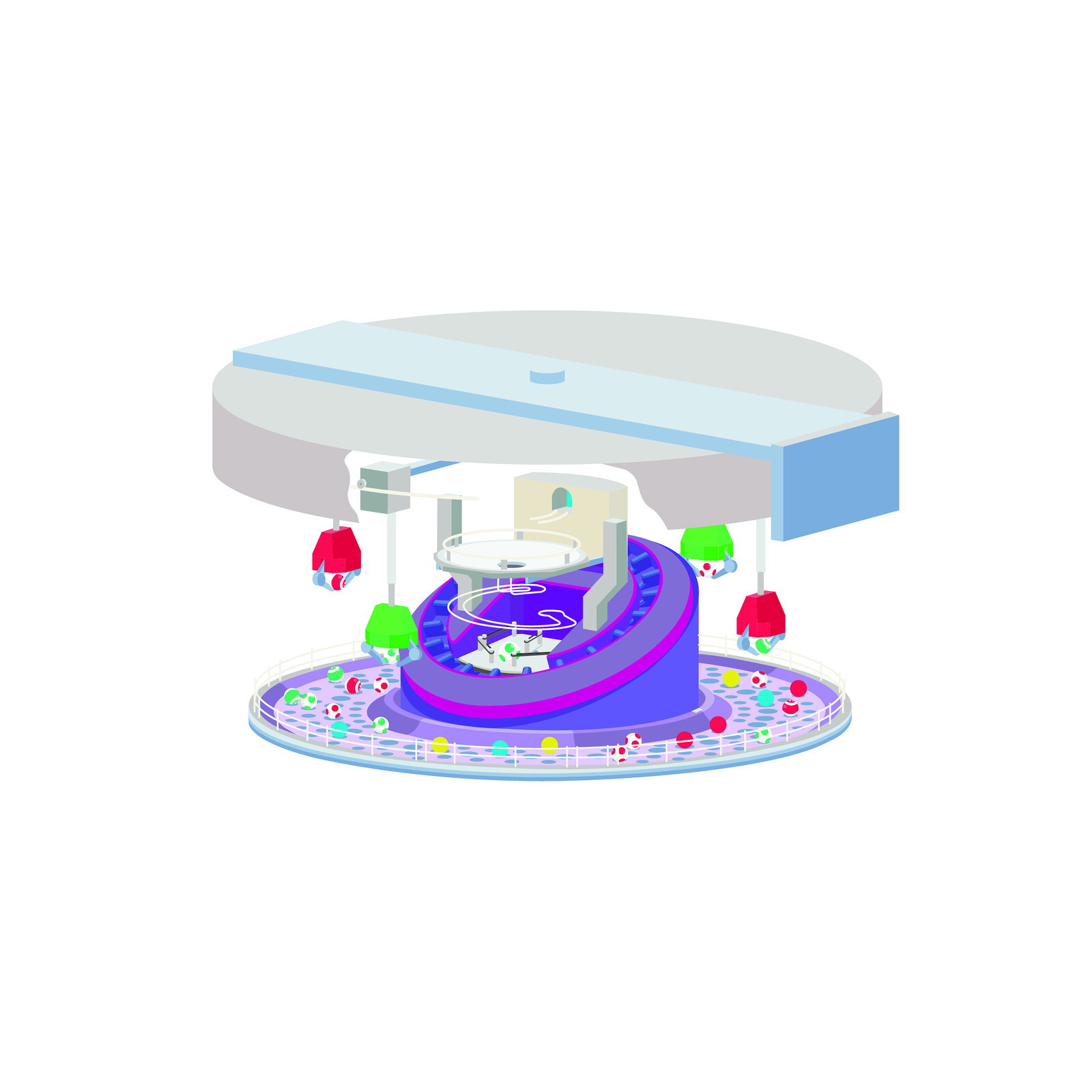

Photo of Kazaaan!!, a medal game by Sega, photograph by author, 2016.

Luke Caspar Pearson, Super Mario Party medal game, 2016. As part of a longer research project into medal games, this study drawing shows the complex and layered mechanisms at work in the cabinet.

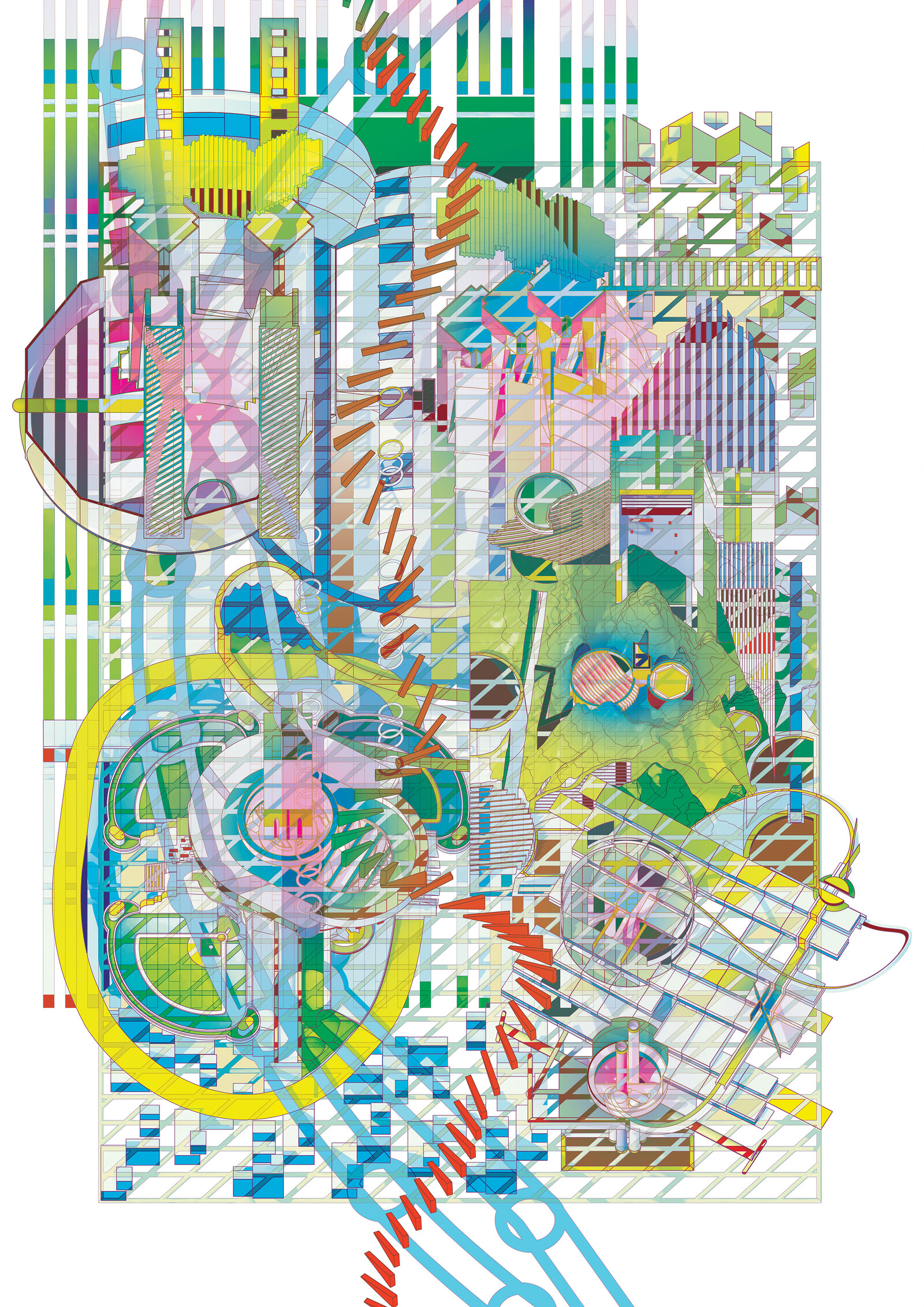

You+Pea, Tokyo Backup City, digital drawing, 2016. The aesthetics of the medal game are translated to an urban scale with drawing used to explore the intensity of such an architecture.

Zhibei Li, Shenghan Wu, and Meiwen Zhang (Videogame Urbanism Studio, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL), Playable Planning Notice, 2017, gameplay footage. This game exploits the looseness of language used in British planning notices, allowing players to prototype alternative structures that would also satisfy the vague language used to communicate to the public.

Towards a Videogame Architecture and Urbanism

Given that videogames combine utopic worlds that are virtually inhabited with complex rule systems for users to engage with, we might suggest videogames are the medium the radical architects of the 1960s and 70s were waiting for—a medium capable of producing playful, quantitative, yet also qualitative utopias that can speak about the real world. Likewise, the work of these architectural visionaries, who splayed ideas across multiple layers, challenges the often solipsistic and isolated nature of game worlds by offering a template for how such imaginary worlds can establish a critical dialogue with reality. If avant-garde architects of the past reflected their society through their conceptual work, we can see games as the media embodiment of computation and communication technologies. As Alexander Galloway argues (like Brayer on Constant): “games are allegories for our contemporary life under the protocological network of continuous informatic control.”19 While this can have negative connotations, games allow us to expose and draw new voices into the often-opaque processes of architecture and urbanism. Games can offer alternatives to traditional systems of governance and regulation. Playable Planning Notice (2017), for instance, is a game interrogating how planning decisions in London are communicated to the population, allowing players to build their own interpretations of information commonly delivered from council to citizen by a laminated A4 document hanging sadly from a lamppost.

Games can also lead us back into re-examining architectural history through virtual spaces. For example, Projectives (2018) explores the Renaissance perspective drawing-spaces of Hans Vredeman de Vries, with players combining different viewpoints together to assemble an architectural perspective in the isotropic. A game space is used to examine the relationship between architectural drawing and form. But there is a further depth to this, given the perspective camera and isotropic grid are encoded within the software used to build the game. As Robin Evans argues: “what else can be drawn in perspective except … things already defined and made according to the regulative lines and planes of classical geometry?”20 In this synthetic world, conventions of architectural representation are exploited to assemble and disassemble space around the players on the fly.

If architecturally trained designers are heading into game design (such as Jose Sanchez’s Block’Hood, 2015 or Greg Kythreotis’ Sable, 2018–) then Tokyo Backup City provides an example of where such practice might be heading in an experimental architectural context. Inspired by a real-world proposal by a Japanese politician for a fallback seat of government located in Osaka that would be built around American-style gambling resorts, the project uses the logics of arcade lottery machines unique to Japan (called “medal games”) to propose a new gamified urban realm. These machines legalize gambling through the transaction of money into game tokens, using elaborate physical and digital mechanism to attract players. Applying their logic at an urban scale would integrate the particularities of Japanese gaming law with smart city technologies to create supersized physical games as economic generators. Developed through drawing, modelling, screenshot generation and game design, the project straddles various media, each carrying different sets of architectural messages. Multiple different versions of the city are encoded within the project, allowing engagement with questions of being within architecture and of the symbolic meaning of architecture through virtual worlds that are never designed to be physically realized.

These various versions of a city are designed to oscillate between utopia and atopia. But of course, this is not so different from multi-layered architectural projects being produced some fifty years ago. What the projects of Archizoom, Superstudio, and others taught us was that the discipline of architecture could be challenged and extended to envelop new media and technologies in a way that was subversive and playful. And in turn, what many of the game worlds here demonstrate is that our conception of space and the actions contained therein can be non-normative and experimental, even in virtual worlds that appear to be recreations of reality. It is important to understand this potential given that games will surely continue to operate as a dominant force in popular culture. Such a context presents an opportunity for a new digital discourse in architecture that leverages the properties of game environments to keep experimental, imaginary, and utopian ideas at the forefront of architectural thought to come. We can now stage new forms of negative utopia and invite people in—not as remote viewers of a world, but as participants in spatial systems that can be reshaped frame-by-frame. By adopting the outlook of Superstudio and the systems of Super Mario, we can challenge the contradictions of today by designing spaces where interface meets ideology, rules meet representation, and the computational meets the conceptual.

McKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory (Cambridge MA, London: Harvard University Press, 2007), Note 199.

Bernard Tschumi, Architecture and Disjunction (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 1996), 122.

Michael Nitsche, Video Game Spaces: Image, Play, and Structure in 3D Worlds (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2008).

Mark Wigley, Constant’s New Babylon: The Hyper-Architecture of Desire, (Rotterdam: Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art/010 Publishers, 1998), 13.

Constant, “Demain la poesie logera la vie” (manuscript, 1956). Reprinted in Berreby, Documents relatifs, 595-596. Cited in Wigley, Constant’s New Babylon, 26.

Marie-Ange Brayer, “Work and Play in Experimental Architecture, 1960-70,” PCA-Stream (2012), ➝.

Pino Brugellis and Manuel Orazi, “Radicals Forever,” Radical Utopias, eds. Brugellis, Gianni Pettena, and Alberto Salvadori (Rome: Quodlibet Habitat, 2017), 38.

Francesca Balena Arista, “Archizoom Associati,” Radical Utopias, 102.

Andrea Branzi, No-Stop City Archizoom Associati (Orleans: HYX, 2006), 176–179.

Lev Manovich, Software Takes Command (New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2003), 44.

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2001), 9.

Louis Marin, Utopics: The Semiological Play of Textual Spaces (Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press, 1984), 242.

Ian Bogost, Persuasive Games (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2007), Kindle edition for iPad, Loc. 4005. See also: Ian Bogost, “The Cathedral of Computation,” The Atlantic (January 15, 2015), ➝.

McKenzie Wark, Gamer Theory (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 2007), Note 119.

Wark, Gamer Theory, Note 118.

Branzi, No-Stop City, 176–179.

Ibid.

Wark, Gamer Theory, Note 119.

Alexander R. Galloway, “Playing the code: Allegories of control in Civilization,” Radical Philosophy 128 (November/December 2004), ➝.

Robin Evans, The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2000), 133.

Becoming Digital is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Ellie Abrons, McLain Clutter, and Adam Fure of the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning.

.jpg,1600)