30 hours.

On Thursday, March 12th, the newspapers were on fire. Every four hours their headlines changed. We woke up to the news that the following week schools would close indefinitely. We had lunch with the announcement that they would be shut down tomorrow. We had breakfast with a state of emergency that brought the army onto our streets. As lockdown settled in, airports and borders closed. We all ran home, and here we remain, in our domestic space, for what seems a new dimension of forever.

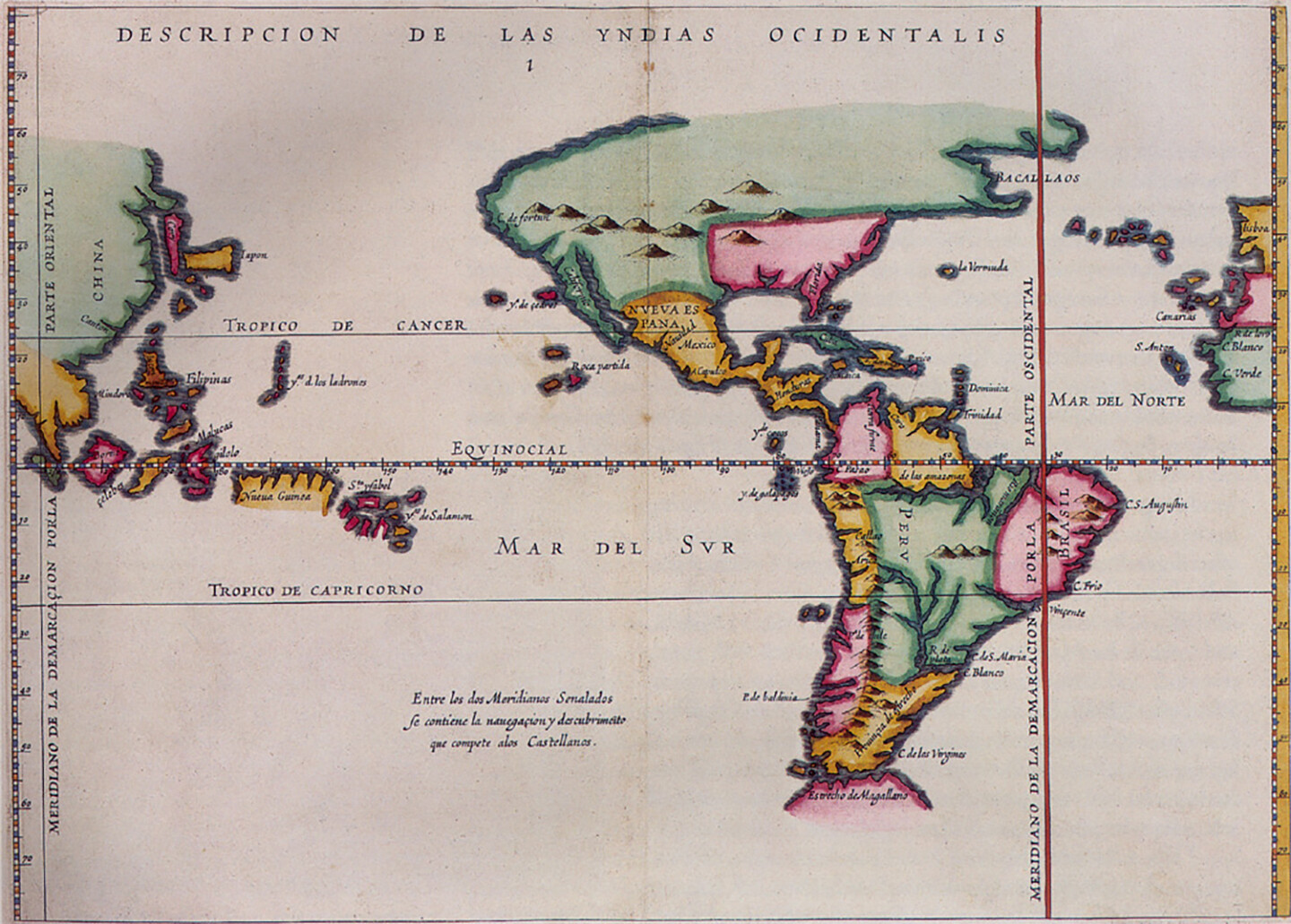

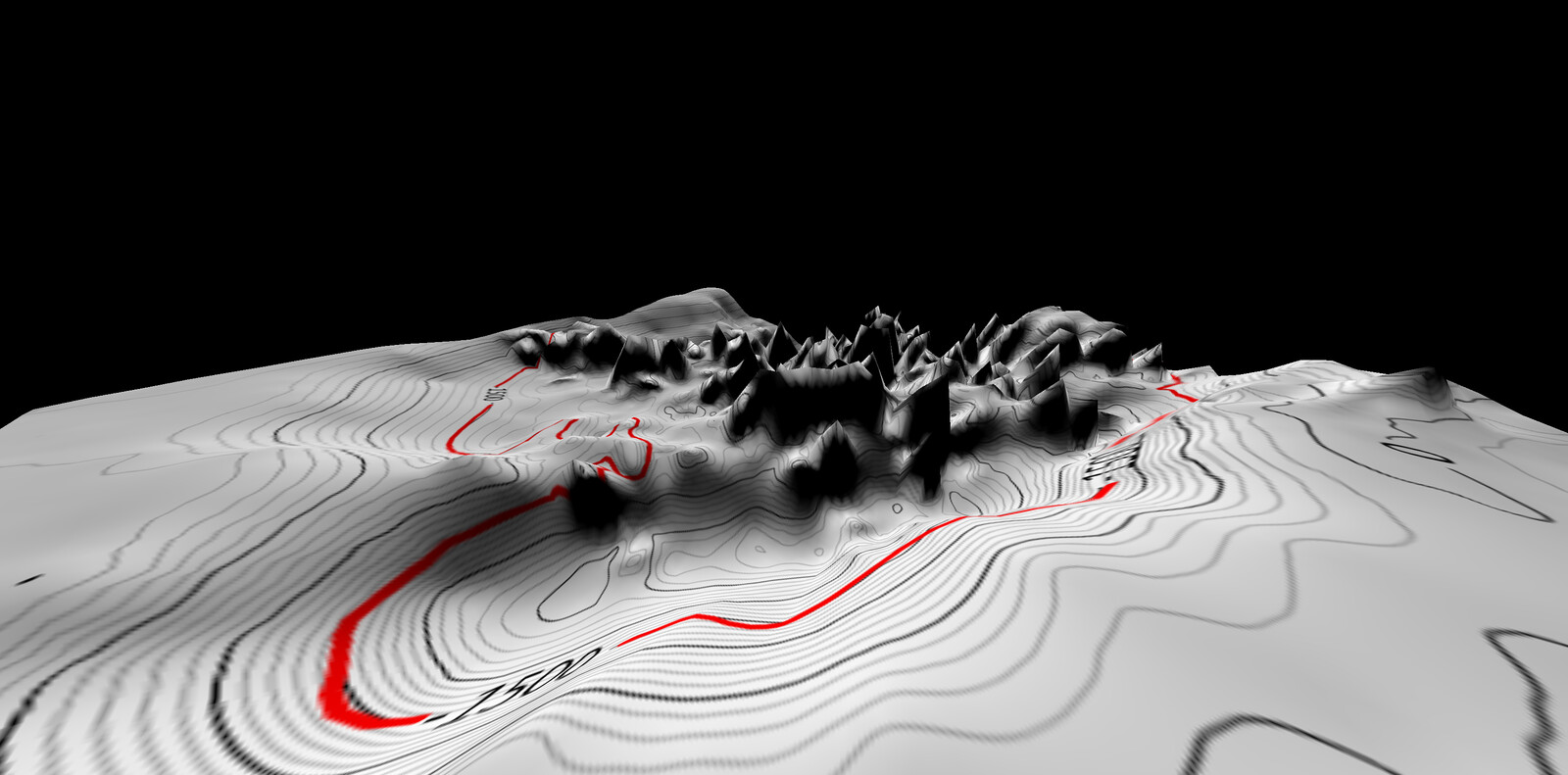

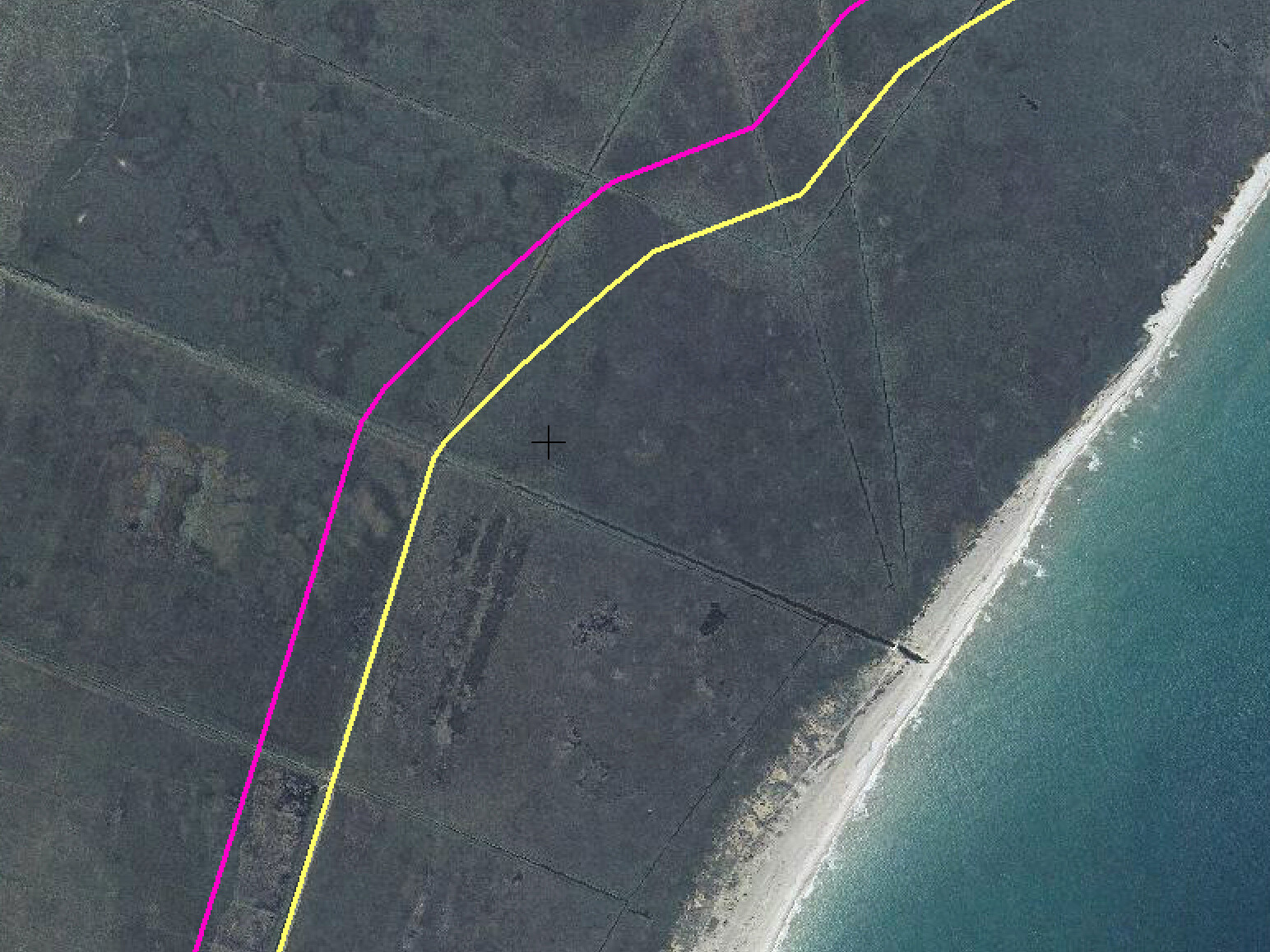

In the midst of latent danger, a battle rages against time. The border to conquer moves inward, reshaping desire in its wake.

1.

We locked the door behind us and looked inside. Time stopped. No one to see, nowhere to go, nothing to buy, no clear future, only rising death outside. A week passes by. A friend writes:

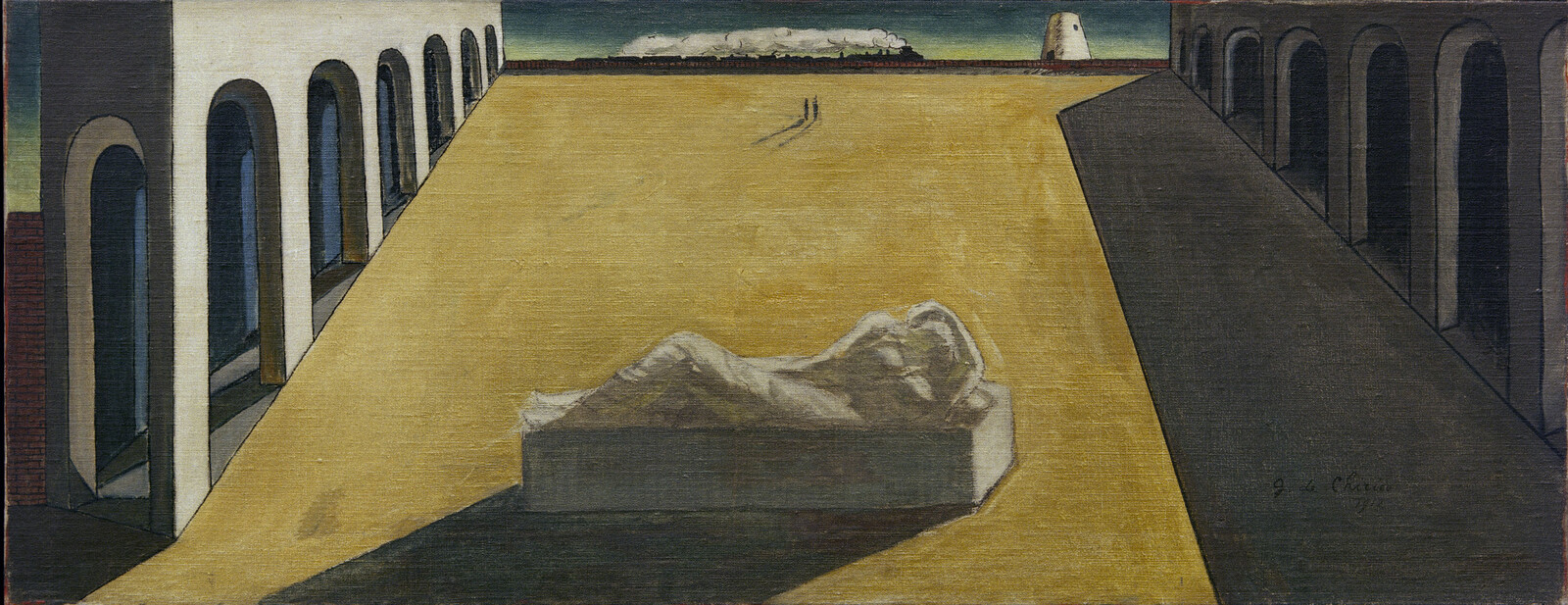

I once read as a child that African prisoners of some tribe, being locked up by British colonial forces because of petty crimes, fell into an unfathomable sadness and stopped eating. They couldn’t foresee an end to captivity because their experience of time didn’t include the future, so they projected that lack of free, limitless space, and died in sadness. Any given time was every time. I’m starting to think this experience, for us riders of passing time, always obsessed with what’s coming next, is a forceful and unexpected reminder of the unending potential of time present as an exploration of time past. Cabin fever versus cabin desire. I’m glad you’re all doing well.

Society is characterized by fear and desire. Desire relates to unattainable space, sex, love, objects. But numbing ourselves with consumption doesn’t work any longer, and we can’t touch anybody we don’t bio-trust or we might end up in a white room and a lonely grave. The absence of a future makes desire go through a deep transformation. The past flashes vividly and the present becomes an implicit truce of suppressed anger. We’ve come to believe that freedom is freedom of choice. But now, what we have is what we have in the circuit of our home, where freedom without the power of novelty has a different flavor. If we can choose to die standing, we can also reconsider everything once failed; an opportunity in the blink of disaster.

2.

A second week passes by. An awkward sense of freedom settles into our domestic kingdom.

Emerging from the train, I found it was fully night, the air excited by foreboding and something else, something like the feel of a childhood snow day when time was emancipated from institutions, when the snow seemed like a technology for defeating time, or like defeated time itself falling from the sky, each glittering ice particle and instant gifted back from the routine.

—Ben Lerner, 10:04

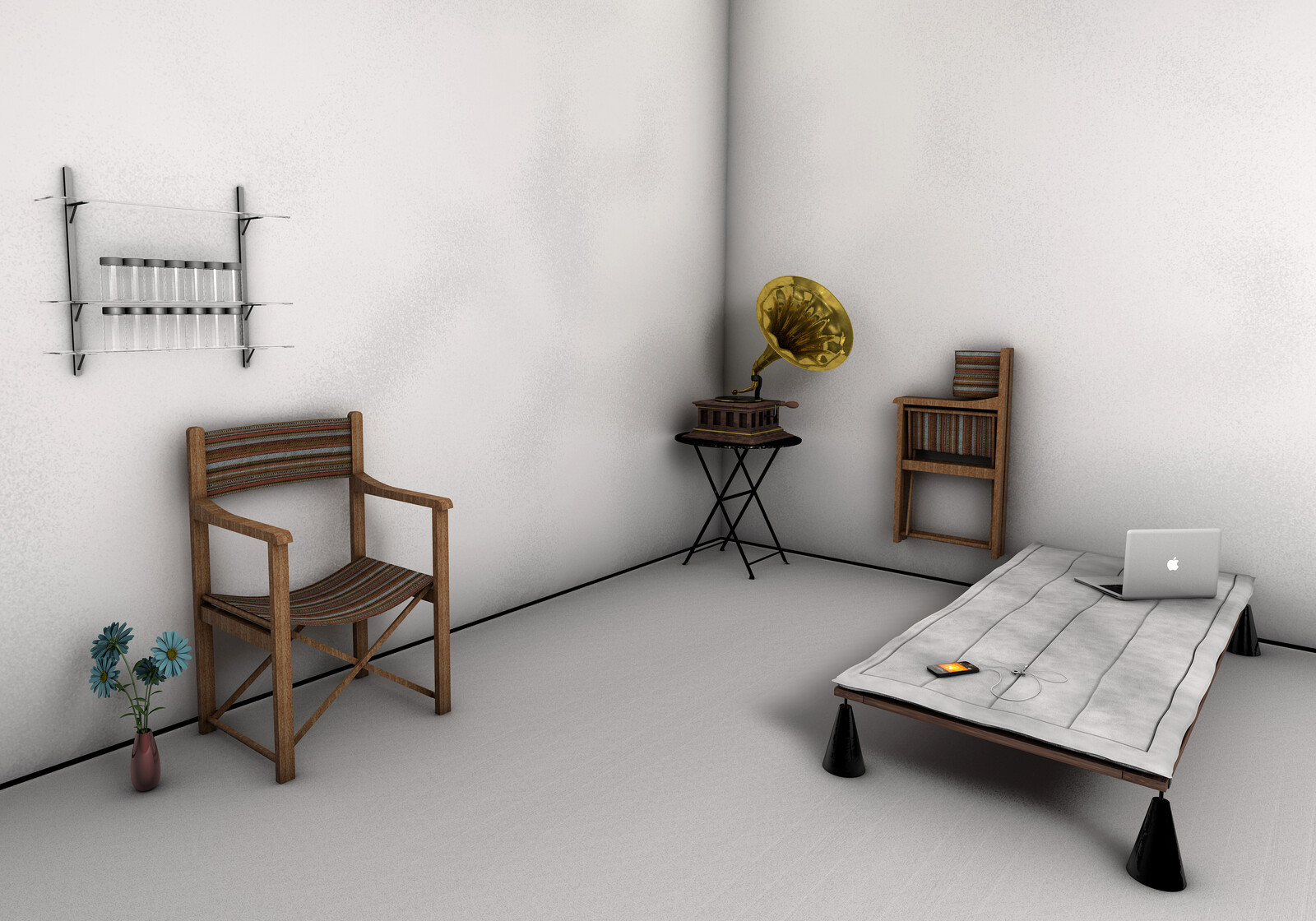

Freedom is no longer related to the future. It is not even related to what you do in the present. Two weeks in and freedom seems to define desire in the opposite direction than before. In the past, freedom meant being able to long for knowledge, beauty, a place, a body, a brain and to construct the conditions to approach the objects of our admiration; Freedom now is not the possibility of stepping into a city, listening to a master, escaping to a mirrored hotel with a lover. In these times, freedom has become the liberation from all desires instead: a continuous thread of containment; an exercise in self-sufficiency. Time outside of the institution. An infinitude of possibilities, all within the galaxy of our own home.

3.

After three weeks of confinement, desire leads to a ruthless sense of danger.

The government runs on the premise that one should NOT trust the people: The people should be loved, protected, taken care of, controlled… A strong state is needed in times of epidemics since large-scale measures like quarantine have to be performed with military discipline.

—Slavoj Žižek, Pandemic!

As lockdown measures become more extreme, a paradox renders visible: confinement has been imposed on us by the very same structure we have built our sense of freedom on. What if security is not the means of assuring freedom, but of losing it altogether? The government stopped foreclosures, but the army polices the streets to limit our movements. Could we be freer in our un-freedom? To enjoy is to trespass. If this situation lasts, we might need to develop an autoimmune system of pleasure to fight against control.

And yet, in its most basic form, the idea of the future is problematic now. A globalized culture of information reminds us every hour that we will be desperately unwell for long. A second roaring twenties await us, just as post-pandemic and recession-filled as the last, but only the chosen class will dance the night away. What our culture brought closer together through technology and education, confinement has brought apart: having a second residence of choice, a fixed salary, a sunny spot at home, a supporting family or none of the above; a pandemic lexicon in the making.

4.

After a month, our homes are fully-working heterotopias.

Fourth principle. Heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time—which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies. The heterotopia begins to function at full capacity when men arrive at a sort of absolute break with their traditional time. This situation shows us that the cemetery is indeed a highly heterotopic place since, for the individual, the cemetery begins with this strange heterochrony, the loss of life, and with this quasi-eternity in which her permanent lot is dissolution and disappearance.

—Michael Foucault, “Of Other Spaces”

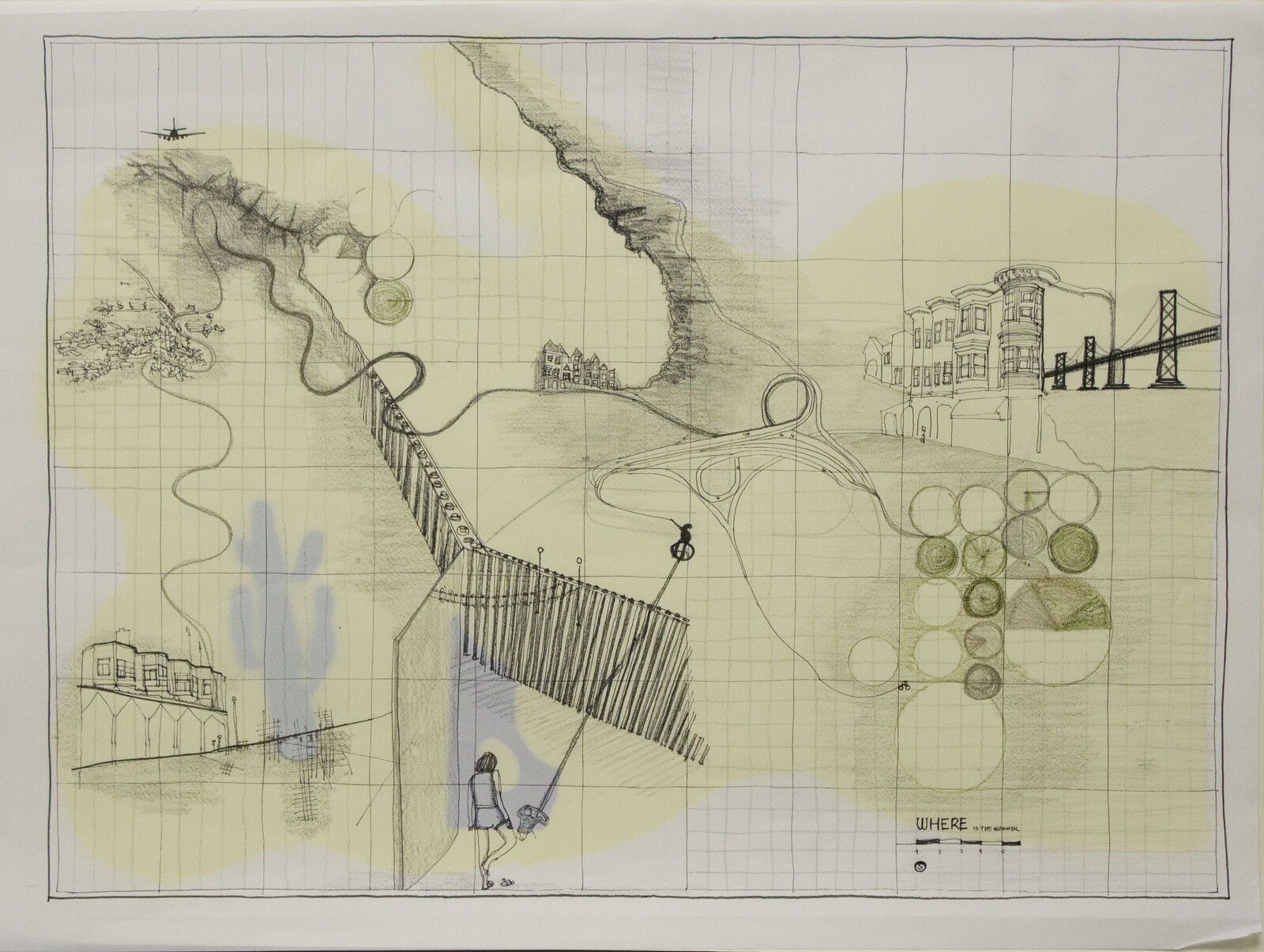

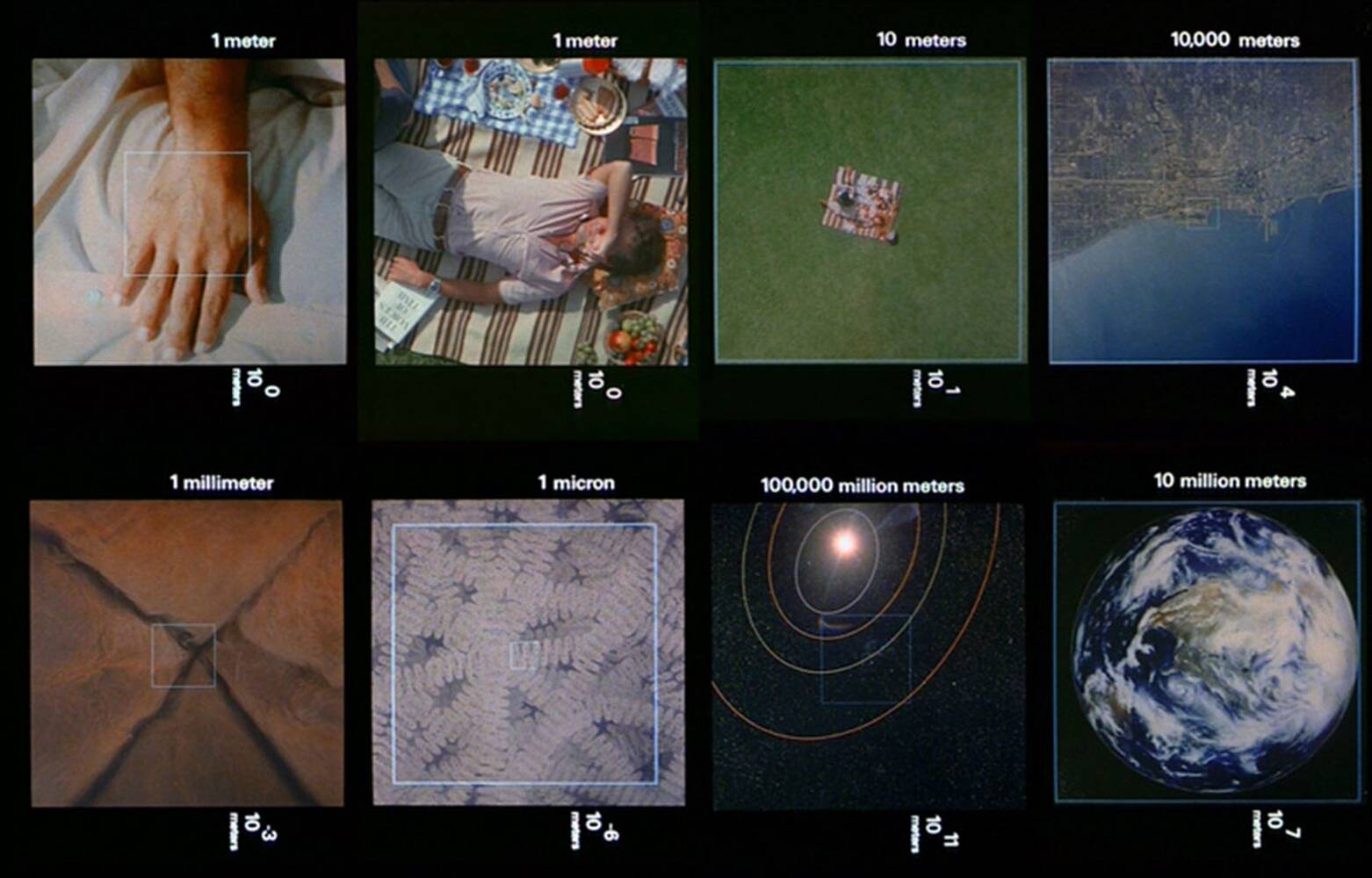

Michael Foucault defined heterotopias, as those spaces capable of juxtaposing sites that are seemingly incompatible. Some heterotopias accumulate time, such as museums or libraries, while for others, such as festivals, time is transitory. There are heterotopias where utopias are contested, and others which are spaces of difference, where individuals of deviant behavior are placed. In these pandemic times, all heterotopias have collapsed into a single space. We live at home, we work at home, we love and hate at home, many die at home too. Domestic space is the new school, the new jail, the new office, the new hospice. Seemingly incompatible activities are juxtaposed: online meetings next to children; divorced couples living together; abusers and the abused, the healthy and the sick, all cohabit under a same roof. Spaces of temporal relaxation, like cinemas and cafes, have become our living rooms and kitchens. Domestic space has been transformed into private towns, with ghettos, restaurants, playgrounds, and productive quarters. Every day we get same views towards the outside, but borders are ever-changing within.

5.

A fifth week ends. Time flies now.

Rather than pass the time, one must invite it in. To pass the time (to kill time, expel it): The gambler. Time spills from his every pore.—To store time as a battery stores energy: the flâneur: Finally, the third type: he who waits. He takes in the time and renders it up in an altered form—that of expectation.

—Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project

René Girard’s mimetic theory explains how desire is always triangular: we desire what our neighbor wants. But the walls of our confinement leave limited space for comparison. We can’t admire the wealth, wisdom, or beauty of anybody else up close. Mimetic desire now only seems to work at a national level, as countries compete for medical protection, a vaccine, or the ultimate promise of digitized disease control.

If desire, by definition, can only exist within a future tense, what happens when projection isn’t possible? With the present immersed in a breathless pause, if a carpe diem attitude doesn’t work, maybe our only hope is to impersonate Walter Benjamin’s flâneur and store time as a battery stores energy.

If we do, we might soon be living in Michael Ende’s novel Momo in reverse: our frozen hours will flourish from every cigarette puff, and the city will burn in a movable feast.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.

Special thanks to Albert Fuentes for inadvertently co-authoring this piece.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.