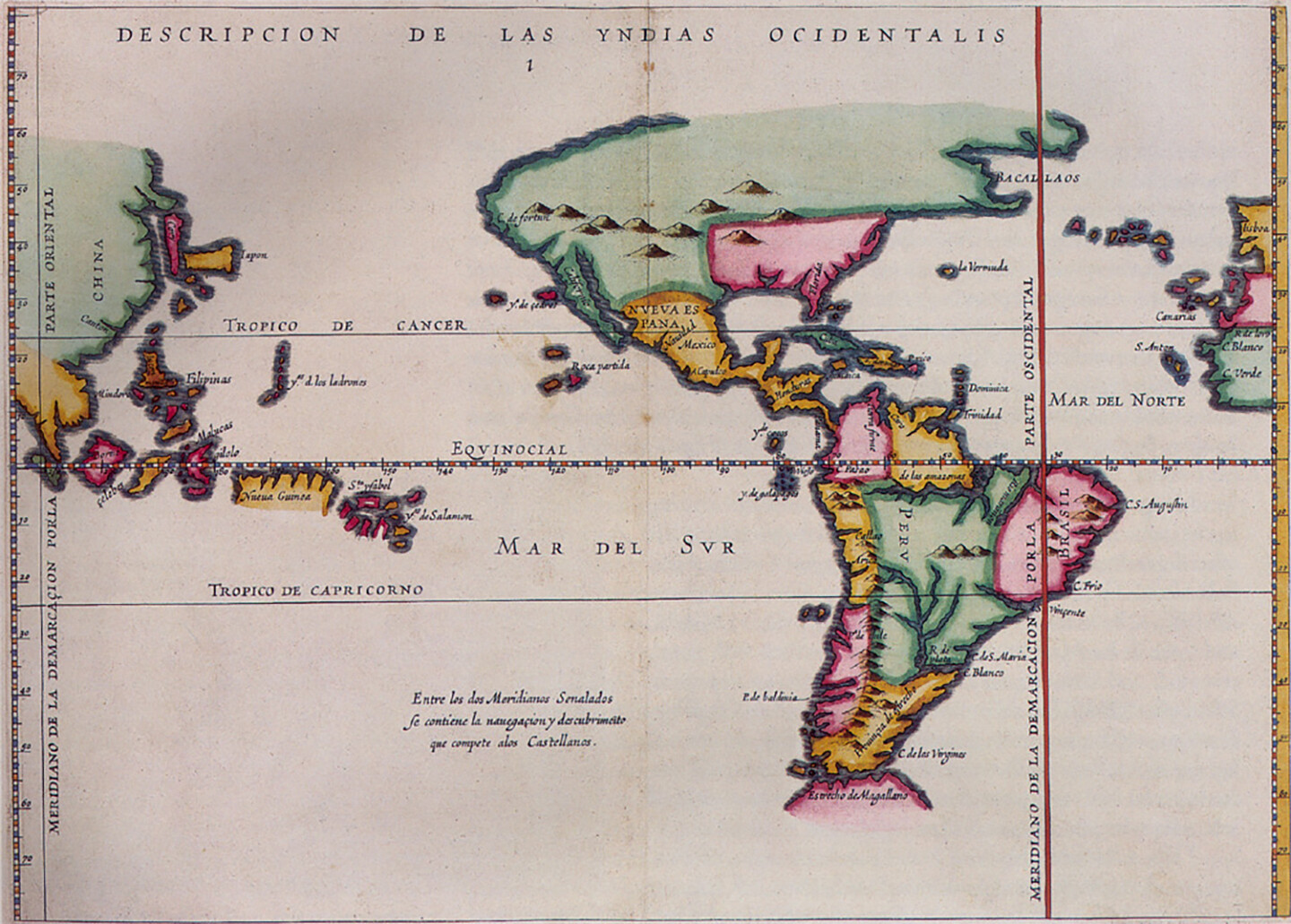

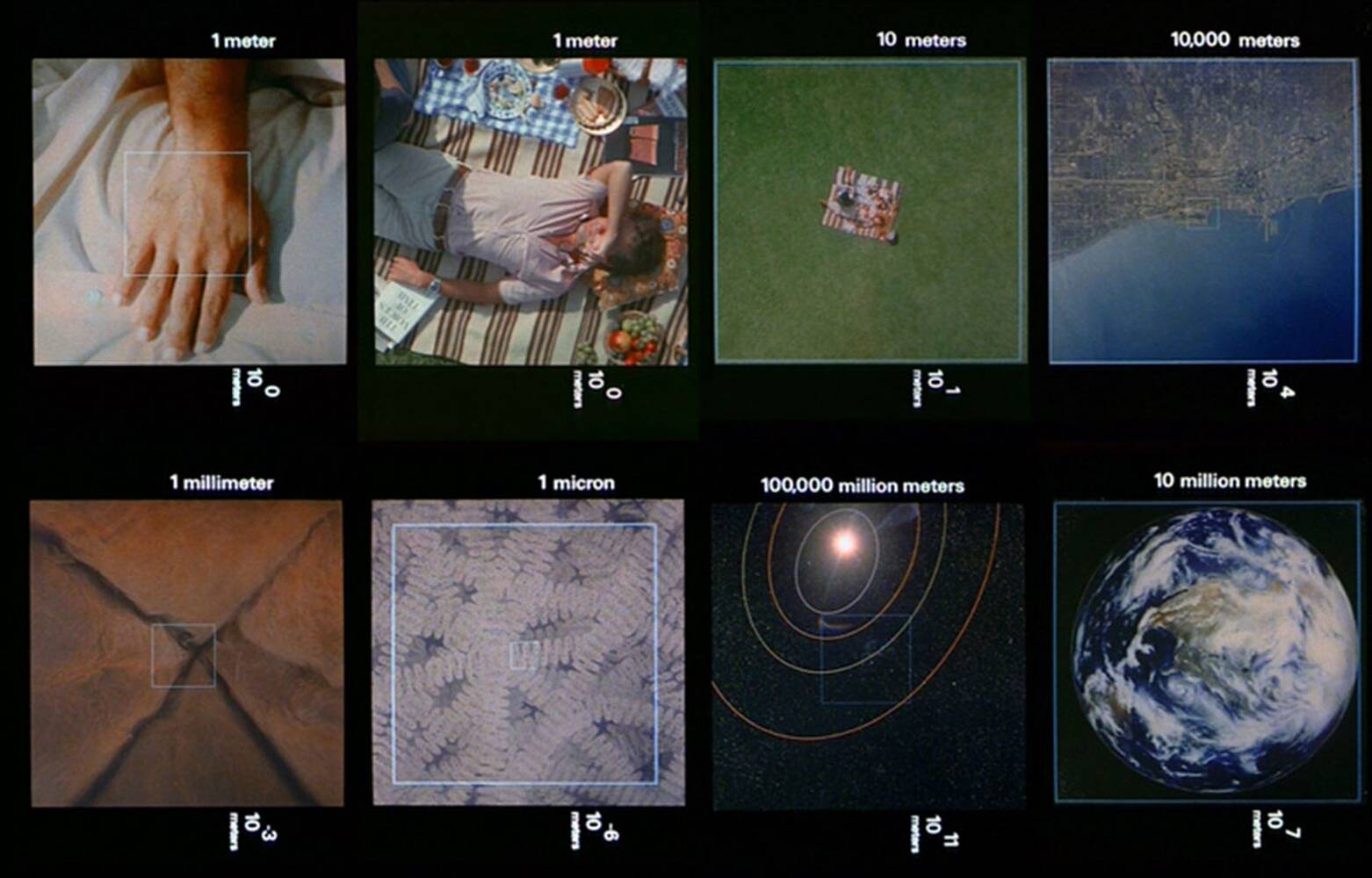

Borders are indispensable to capital’s formatting of the world. As social institutions, borders not only mediate relations of capital and state but also establish boundaries, limits, interfaces, and zones that register the profound transformations effected by capital’s operations across and beyond existing territorial demarcations.1 The town of Tseung Kwan O in the New Territories of the Hong Kong Special Autonomous Region (SAR) is a site that bundles and multiplies these changes and variations. This restless spatial reorganization is most evident in the borders that separate its data center cluster, waste dump, and the nearby LOHAS Park real estate development.

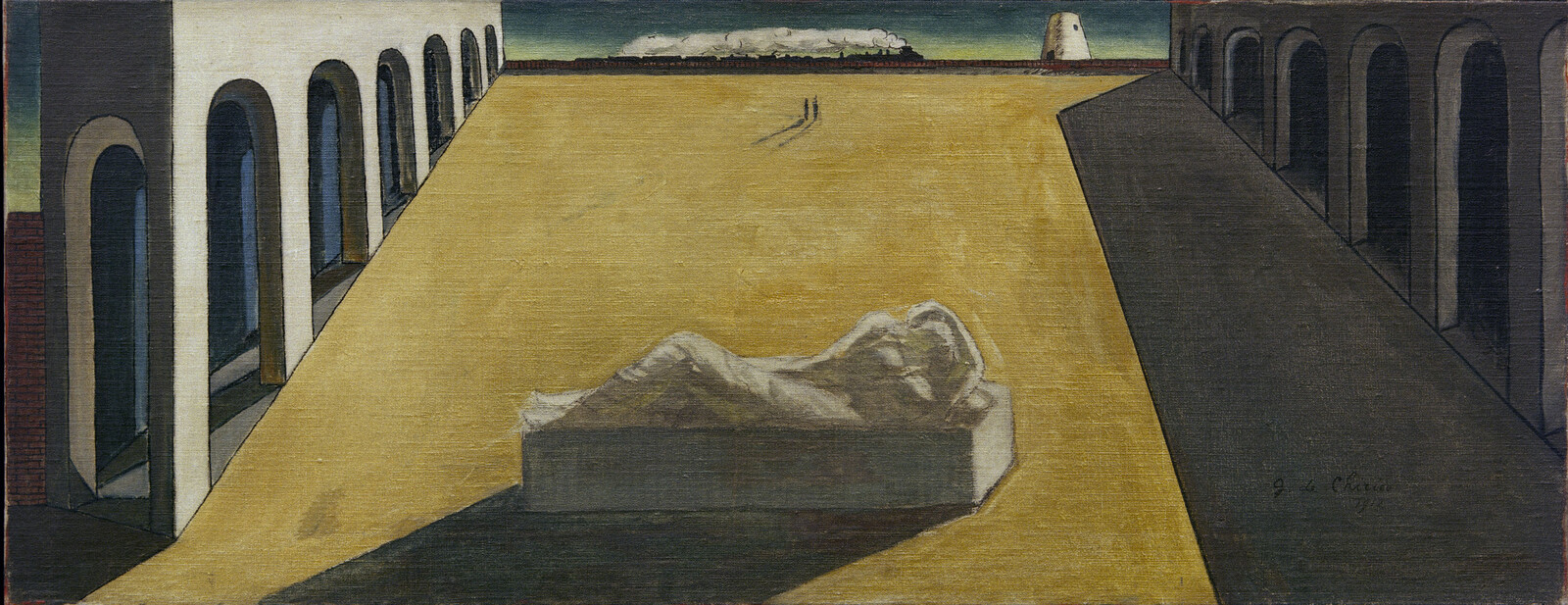

Tseung Kwan O hosts one of the largest commercial data center clusters in the world. Located on reclaimed land close to undersea cable landings and linked to digital infrastructures that support financial trading on the opposite shores of Hong Kong Island, the site is a crucial gateway and switch-point between the mainland Chinese and global data environments. Tseung Kwan O is also the site of one of Hong Kong’s main waste dumps, the South East New Territories (SENT) Landfill. Close to capacity and under pressure from population density and land prices, the dump abuts the data center cluster in the Tseung Kwan O Industrial Estate. This complex of spatial and infrastructural relations creates a series of borders that both crisscross the area and extend beyond it. To conceive of Tseung Kwan O as a borderland is to probe divisions between East and West, liberalism and state capitalism, data and waste. Far from the vision of a border as a line separating distinct territories, investigating space, technology, and waste at Tseung Kwan O illustrates how borders not only proliferate across political and physical landscapes but also interact with each other to produce worlds.

In accordance with logics or operations that make capitalism as a system function, specific executables, spatial arrangements, and protocols articulate Tseung Kwan O’s bordering dynamics. Facilities such as data centers and waste dumps are not just local infrastructural manifestations of changing global patterns of supply, demand, and logistical connection. These installations emerge as both control centers and sites of spillage that capital requires and works through to continue its relentless process of shaping and terraforming the planet. Tracing the crystallizations of data and waste production, distribution, and valuation at Tseung Kwan O thus contributes to a larger project that attends to the operations that encode capital’s encounters with its multiple outsides, and the possibilities for resistance or disruption that follow from these interactions.

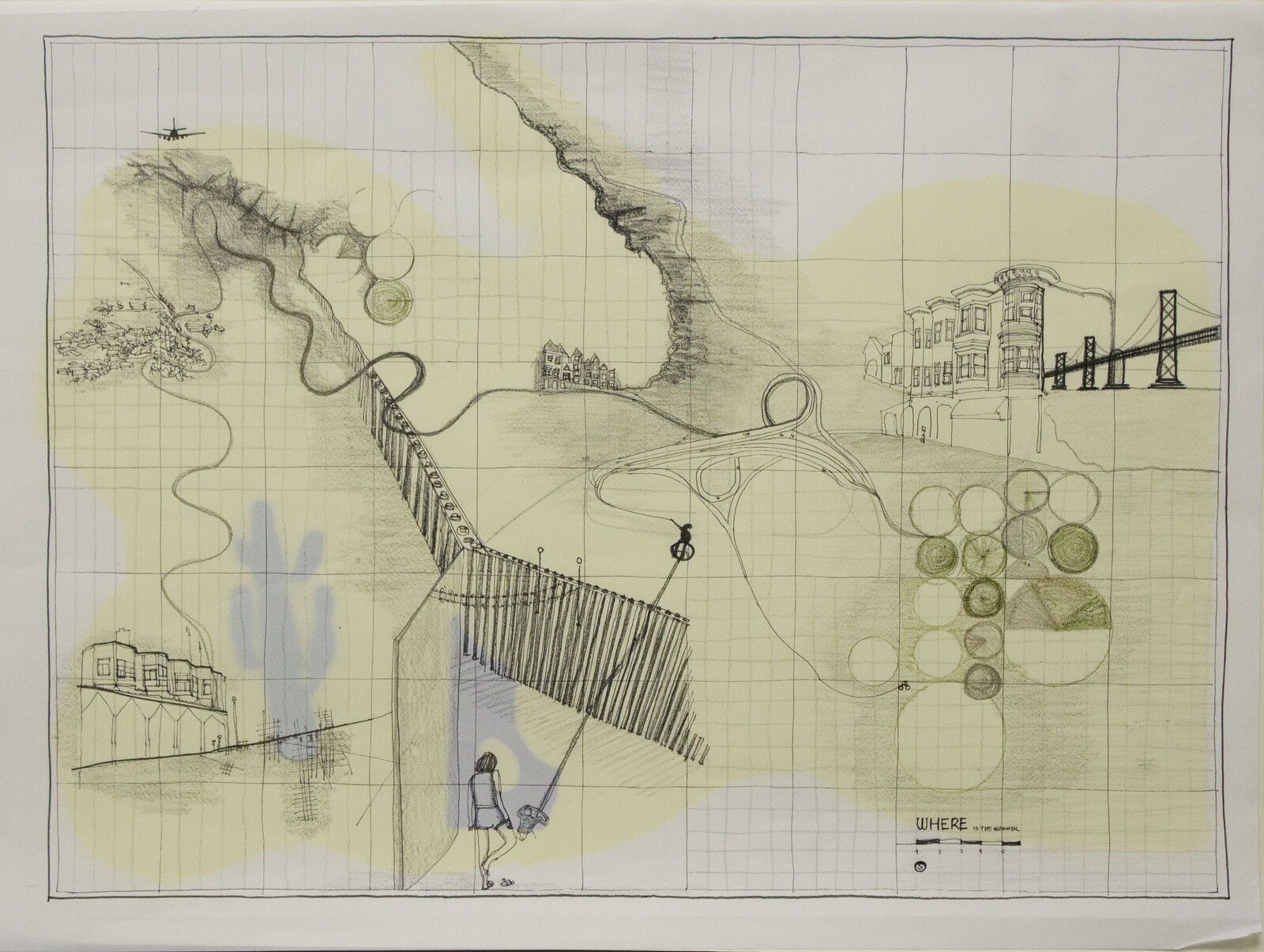

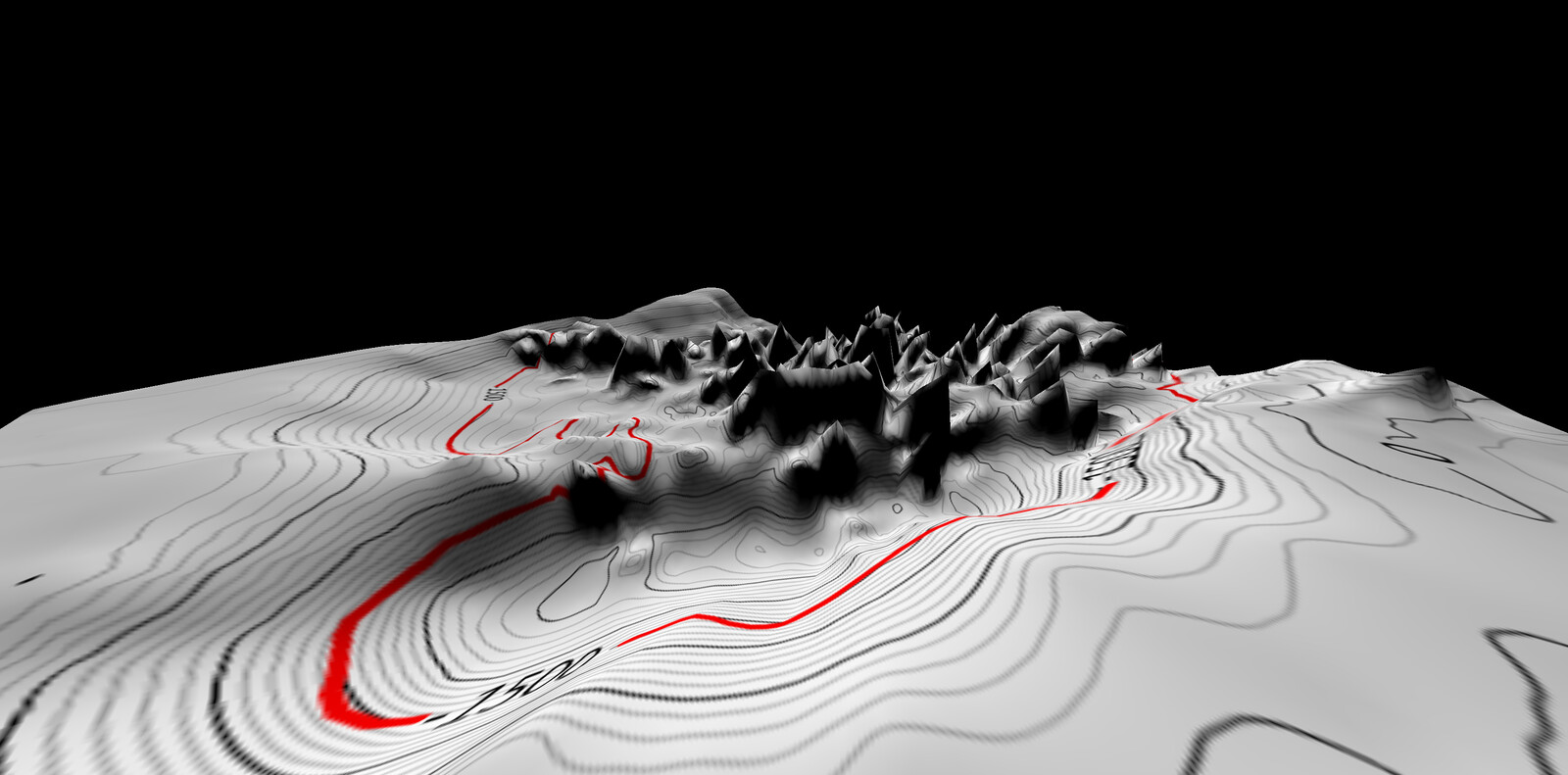

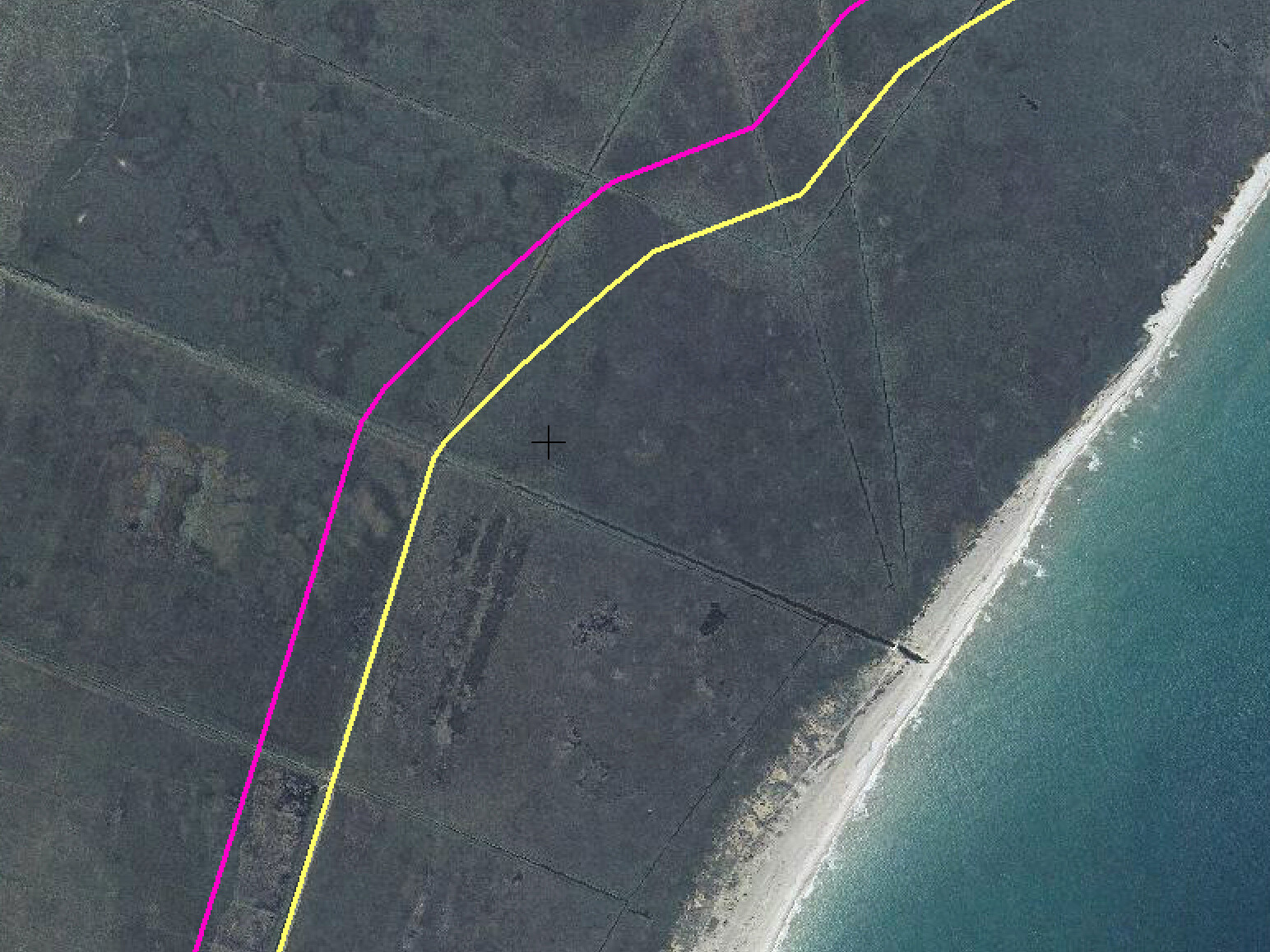

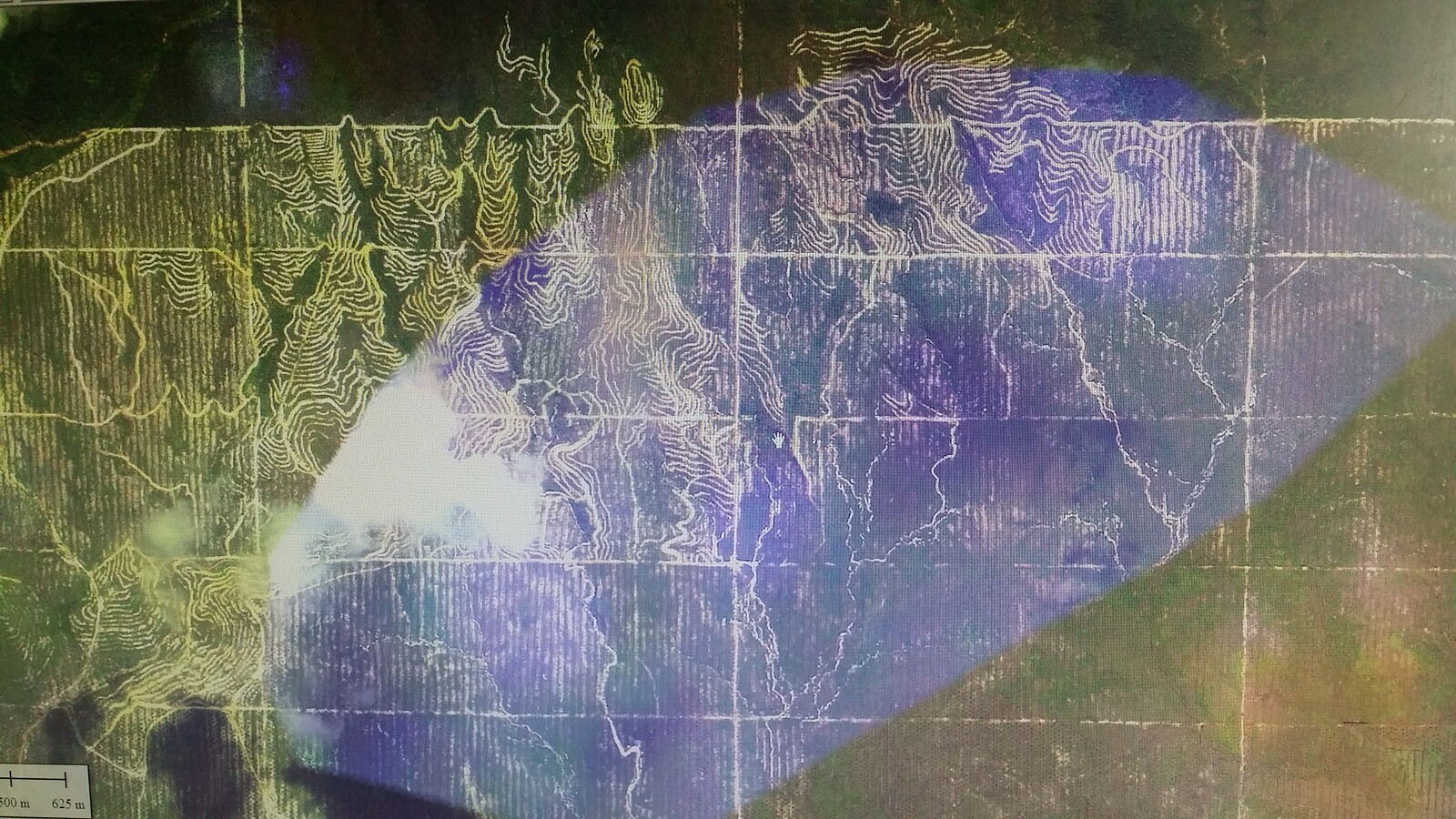

Plan of South East New Territories Landfill Extension. Source: Environmental Protection Department, Government of the Hong Kong Special Adminstrative Region.

Tseung Kwan O is also a borderland because it hosts facilities that draw in materials from wider geographical vistas, creating opportunities for aggregation, treatment, and analysis. In the case of the SENT Landfill, these materials are designated as waste, and although their origins are encrypted in tangled webs of supply, they are most immediately sourced from across Hong Kong’s dense urban fabric. By contrast, data centers assemble electronic information, which is stored, processed, and transmitted in binary form through complexly arrayed networks of digital switches. Connected to the wider world by undersea cables, Tseung Kwan O’s data centers serve clients across a potentially global expanse, but derive their locational advantage primarily from their proximity to China’s mainland data industries and markets.

Insofar as their operations catalyze and unsettle the production of borders, data centers index the emergence of capital as a direct political actor. Due to the role of data in transforming economies and social relations, these facilities function not only as technical infrastructures but also as de facto political institutions that inscribe, challenge, and defend established monopolies of jurisdiction and sovereignty. Their capacity to generate topologies of power that exceed state borders crosses their material location within existing political territories and subjection to patterns of regulation and oversight that abide by geopolitical relations of national division and regional competition. Nowhere is this clearer than in Hong Kong, which, as a Special Autonomous Region of China, enjoys proximity to the mainland while maintaining a distinct economic and administrative system.

The world’s shortest submarine fiber optic cable—only 2.76 kilometers-long—connects Tseung Kwan O and Chai Wan.

The slogan “one county, two internets” is popular among digital activists who seek to preserve a free and open internet in Hong Kong. However, the conditions described by this phrase also give rise to Hong Kong’s emergence as a data center hub. As data center consultant Jabez Tan explains:

It’s a gateway in the sense that digital business flows through it both ways: international companies use it to get into China, and Chinese companies, from search engine and cloud giants to online gaming and mobile app developers, set up shop in Hong Kong before they branch out into Southeast Asia, Europe, or North America.2

The figure of the gateway features widely in discussions of Hong Kong’s relation to the mainland, particularly regarding operations of capital and finance. Even if many of the mainland’s first-tier cities now eclipse Hong Kong in terms of contribution to gross domestic product, the unique territorial situation of the SAR makes it amenable to data center development. The gateway is a figure of the border: a device of entry and exit capable of opening and closing. Yet it is not a switch with only two settings, on and off. As figure, it invokes the possibility of filtering, speeding up or slowing down, letting some through and shutting others out, including differentially as well as excluding. The ground against which this figure emerges is the contested terrain of Tseung Kwan O. This ground is not only physically contingent, given that it is reclaimed from the sea and susceptible to leachate leakage from the landfill, but also contingent in a social and political sense, subject as it is to urban conflicts and design protocols that privilege vertical relations of circulation and habitation above grounded practices of sociality.

Recent studies of digital infrastructures focus on their capacity to act as media of polity by establishing technical territories that complicate geopolitical relations as comprehended through representational frames of international relations and civilizational divide.3 Placing emphasis on borders draws attention to how digital infrastructures introduce patterns of connectivity that articulate capital’s operations to logics of circulation, separation, and filtering. If we understand data centers not only as infrastructures but also as political institutions, these logics acquire a force that permeates the storage, processing, and transmission of data as it extends into social worlds.

At stake are not primarily questions of access to digital media or the bias built into algorithms, although these problems surely raise issues of bordering. Neither are the uses of digital technologies in securitizing borders and tracking the movement of people and things. Rather, the workings and physical setting of data centers at Tseung Kwan O bring to the fore the ways in which borders mediate relations among economy and geopolitics, at least insofar as these domains are subject to transformations driven by data’s centrality to contemporary life.

The presence of the waste dump at Tseung Kwan O adds a layer of complexity to these relations. Although its adjacency to the data center cluster is a matter of urban planning that seems fortuitous with respect to data center operations, the proximity of the landfill creates a spectacle that beckons analysis. China’s great firewall has been crucial to its data sovereignty concerns and has guided the choice of many international companies to establish data centers in the less restrictive Hong Kong. In the field of waste management, the National Sword policy, which restricted the import of recyclable waste to China in 2018, has placed pressure on Hong Kong’s landfills, reshaping their operations and physical form. The border between Hong Kong and mainland China thus insinuates itself into the data center cluster and the waste facility alike. Without considering the massive amount of energy expended in data centers, the efficiency of their operations, or the conceptual and material borders between data and waste, it is possible to see that these relations play themselves out in ways inseparable from capital’s geopolitical and extractive dynamics.

The Hong Kong-China land border is a porous barrier with an expiration date. Despite the presence of walls and a closed frontier area, population movements as well as the construction of bridges, tunnels, artificial islands, and a high-speed rail link have tested this border as something fixed in time. Given the liberal precepts governing social and economic life in Hong Kong and the contrasting political styles of the mainland party-state, the Hong Kong-China border has become, for many, a symbol of a supposed civilizational split between East and West. In a sense, the Hong Kong protest movements of 2019–2020 can be read as a struggle for the strengthening of this border, at least insofar as they opposed a bill that allowed for extradition of criminal suspects to the mainland.

Clearly, the reasons for the social unrest do not reduce to a single trigger and relate more widely to pressing issues of political rights, democracy, and social repression. Nonetheless, the stance of “localism” and the claim that “Hong Kong is not China” imply a logic of bordering. Likewise, the reaction in Hong Kong to the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was a strong social demand for closure of the border, although three crossing points remained open. In the longer run, however, the opening of this border is a process underway and likely to be complete well before 2047, when the current arrangement governing Hong Kong’s relation with the mainland ends. At the same time, as evident at Tseung Kwan O, the border articulates itself far from its physical infrastructure on the ground.

As cross-border movements of capital, labor, and other commodities become increasingly reliant upon digital technologies, the role of data centers as important hubs of storage, processing and transmission comes to the fore. Etienne Balibar’s observation that “the border is no longer at the border” acquires new salience at Tseung Kwan O.4 Reading the Hong Kong-China border back into this site means coming to terms with the shifting relations between the former British colony and the mainland. Today, borders provide a powerful entry point for investigating the articulation of global capitalist processes, such as valorization, accumulation, and extraction, and power assemblages, such as sovereignty, law, and governmentality. Hong Kong’s unique positioning tests the assumption that national boundaries and capitalist systems are coterminous. In the wake of China’s opening to the global market since 1978, the contrast between a planned economy on the mainland and free market capitalism in Hong Kong can no longer stand. There is a need to understand the co-evolution and deep interconnections between these economies and their role in shaping geopolitical relations.5

The circumstance surrounding the construction and operation of Tseung Kwan O’s largest data center is a case in point. Opened in 2017, the project resulted from a partnership between the UK-based firm Global Switch, China Telecom, and Daily Tech (a mainland data center operator). Similarly, the TGT Hong Kong 2 Data Center, which opened in 2014, is a collaboration between Alibaba Cloud, Huawei (which supplied the hardware), and Towngas Telecom (a wholly owned subsidiary of one of Hong Kong’s oldest listed companies). In Tseung Kwan O, lines of national affiliation twist. The site is renowned for Google’s withdrawal of its plans to build a data center in 2013, and has been used as a launch pad by Chinese firms such as the state-owned China Unicom that seek to extend their international footprints. However, despite a gradual shift from housing the servers of US operators to supporting the expansion of China’s digital enterprise, the infrastructural and institutional arrangements that animate Tseung Kwan O’s data centers attest to a heavy admixture of mainland and international interests, state subsidies, private and public investments, and collaborations between firms with distinct technological capabilities.6

Plan of Tseung Kwan O Industrial Estate. Source: Hong Kong Science & Technology Parks Corporation.

Hong Kong’s government has deliberately encouraged the data center industry, setting up a Data Center Facilitation Unit in 2011 to offer advice on matters such as statutory processes and compliance requirements. Bolstered by such efforts, the emergence of the Tseung Kwan O cluster lies in earlier governmental initiatives. Ngai-Ling Sum and Bob Jessop detail two reports received by the Hong Kong government in the 1990s: The Hong Kong Advantage, prepared by Harvard University, and Made by Hong Kong, prepared by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.7 The former recommended that Hong Kong should focus on financial services, and the latter suggested intense capital investment in advanced technological and manufacturing facilities. While the first path has definitely shaped the path of financial capitalism in Hong Kong, the latter did not completely disappear in terms of policy. In 2002, the government established the Hong Kong Science and Technology Parks Corporation, which runs the Tseung Kwan O Industrial Estate.

The emergence of the industrial estate links to land reclamation and development plans initiated in the early 1980s to build Tseung Kwan O as one of Hong Kong’s nine new towns. The reclamation that allowed the development of the estate finished in 1997. The adjacent SENT Landfill opened in 1994, itself partially occupying reclaimed land and run by Green Valley Landfill Limited, a subsidiary of Veolia. The story of relations between the data center cluster and the landfill often takes on secondary importance to a narrative that describes how the waste dump affects quality of life and housing prices in nearby housing estate developments, which were also part of the new town plan. Tseung Kwan O is now home to over 400,000 residents. The data center cluster provides a border that separates the landfill from large housing estates, such as LOHAS Park to the north. A dense development of residential towers, some up to seventy-six stories high, LOHAS (which stands for Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability) Park consists of several complexes with names like The Capitol, Le Prestige, and Malibu. Writing of life in these towers, Frank Chen observes:

Interconnected footbridges link all blocks, channeling residents to a few pre-designed routes via the malls to train stations or their respective estates. If you look for a detour you will find that there’s none; if you descend the footbridges or walkways, you will reach the ground level of nothingness: streets have no names, no shops, no pedestrians, just highways and wire fences that keep you away from an otherwise walkable waterfront area. Parents even warn kids not to go to the ground level as there’s no one down there and it probably isn’t safe.8

Affirming the vision of Hong Kong as a city “without ground,” this residential arrangement packs volumetric urbanism into a tight compact of three-dimensional circulation networks that join shopping malls, transport interchanges, and apartment buildings.9 The verticality of LOHAS Park also provides a kind of olfactory wall that absorbs stench from the SENT landfill. Although the dump receives only building waste since early 2016, the question of how fumes emanating from it interact with nearby housing occupies local activism. Protests against a proposed extension to the landfill, approved in 2014, led to tumultuous events in Hong Kong’s Legislative Council, including the unfurling of a Nazi flag by a councilor. There is even a big data analysis of the landfill’s impact on LOHAS Park that correlates resident complaints with rising real estate prices to conclude that publicity associated with protest draws buyers who discover that only part of the estate experiences odor.10 It is credible to imagine that the datasets analyzed by this study are stored in data centers in Tseung Kwan O Industrial Estate, which now houses over ten large-scale facilities run by Chinese and international companies. However, the question of how spatial proximity between data and waste informs the more general relation between the two is complex and contested.

Speculative development in and around Tseung Kwan O, aiming to reduce the damage caused by typhoons and reclaim more land for housing. Source: Farrells, 2018.

The topographical border between the data center cluster and the landfill cannot simply double for the conceptual border between data and waste. There is a need to ask how the operations that govern the movement, collection, and treatment of data and waste respectively redouble on the physical border between the facilities in Tseung Kwan O. Celia Lury, Luciana Parisi, and Tiziana Terranova discuss how new topologies of power emerge through the production of relational spaces such as those established by digital networks.11 They distinguish between kinds of continuity that operate extensively (in terms of distance and nearness) and those that operate intensively, through circulatory practices of ordering, coding, representing, and regulating difference.

Data centers establish such complex relations of continuity and difference, connecting servers, clients, users, and firms. In industry parlance, “north-south” traffic establishes extensive links between data centers and external clients, while the heavier “east-west” traffic funnels information intensively between servers in the same facility, mediated by network topologies with names like Clos, Fat-Tree, PortLand, and Hydera. A single external query can generate a massive amount of internal traffic, as servers in a facility share and extract data before coordinating and returning a response.12 Waste circuits also configure a two-way relation between extensive relations that bring distant objects and sites into proximity and intensive practices of collecting, sorting, dismantling, recycling, and so on. Changes of intensive formatting, such as the restriction of the SENT landfill to construction and demolition waste, radiate out. But variations from afar can also effect local practices, as became evident in Hong Kong when the mainland introduced the National Sword policy, leaving the city to cope with a deluge of refuse that otherwise would have moved across the border.

Given the propensity of both data and waste circuits to support fungible schemes, we can ask how the topography of geographical location crosses the topology of network variations in the generation of economic value resulting from these circuits as well as from their intersections. Such a style of analysis means not only probing how the production of space inflects the circuit of capital. It also implies investigating how capital’s operations tangle with each other to produce variegations of capitalism such as those that straddle the Hong Kong-China border while also sculpting distinct contours of extraction, exploitation, and accumulation in different material locations.13 Beyond notions of the network society, which oppose segmented places to an ahistorical space of flows, the approach signaled here highlights the role of borders in enabling, regulating, and impeding connections across global difference.

In considering the relations among data and waste, a focus on bordering takes us beyond casual parallelisms: cataloguing the useless information stored in data centers, tracing the role of data analytics in waste management, quantifying the energy burnt keeping backup diesel generators idling over in data centers, understanding spam economies, and so on. These are all worthwhile empirical projects, but lest they merely affirm visions of waste as rubbish, trash, or excess, we need to inquire how the economies they support operate in the nexus of intensive and extensive spatial relations. In this way, we can begin to discern how digital infrastructures articulate operations of capital to changing geopolitical formations.

Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).

Yvgeniy Sverdilk, “Hong Kong, China’s Data Center Gateway to the World,” Data Center Knowledge, February 1, 2016, ➝.

Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (New York: Verso, 2014).

Étienne Balibar, Politics and the Other Scene (London: Verso, 2002).

Jamie Peck, “Hong Kong at the Edge,” June 18, 2018, ➝.

Luke Munn, Red Territory: Forging Infrastructural Power, Unpublished manuscript (2020).

Bob Jessop and Ngai-Ling Sum, “An Entrepreneurial City in Action: Hong Kong’s Emerging Strategies in and for (Inter)Urban Competition,” Urban Studies 37, no. 12 (2000): 2287–2313.

Frank Chen, “Tseung Kwan O: When Urban Planning Goes Wrong,” Ejinsight, September 28, 2016, ➝.

Adam Frampton, Jonathan D. Solomon, and Clara Wang, Cities without Ground: A Hong Kong Guidebook (San Francisco: ORO Editions, 2012).

Rita Yi Man Li and Herru Ching Yu Li, “Have Housing Prices Gone Down with the Smelly Wind? Big Data Analysis on Landfill in Hong Kong,” Sustainability 10 (2018), ➝.

Celia Lury, Luciana Parisi, and Tiziana Terranova “The Becoming Topological of Culture,” Theory, Culture & Society 29, no. 4/5 (2012): 3–35.

Brett Neilson and Tanya Notley, “How Data Centres Produce New Topologies of Data and Labour,” Data Farms: Circuits, Territory, Labour (2019), ➝.

Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, The Politics of Operations: Excavating Contemporary Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.