The South China Sea is a semi-enclosed sea. It is located south of China and Taiwan; east of Vietnam; and west and north of the archipelago composed by the Philippines, Malaysia, and Indonesia.1 The South China Sea encompasses an area of around 1.4 million square miles.2 Ten countries border the South China Sea, namely (clockwise from the west): Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia.3 Six of these states have overlapping claims on the South China Sea and its riches, namely: China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei.4

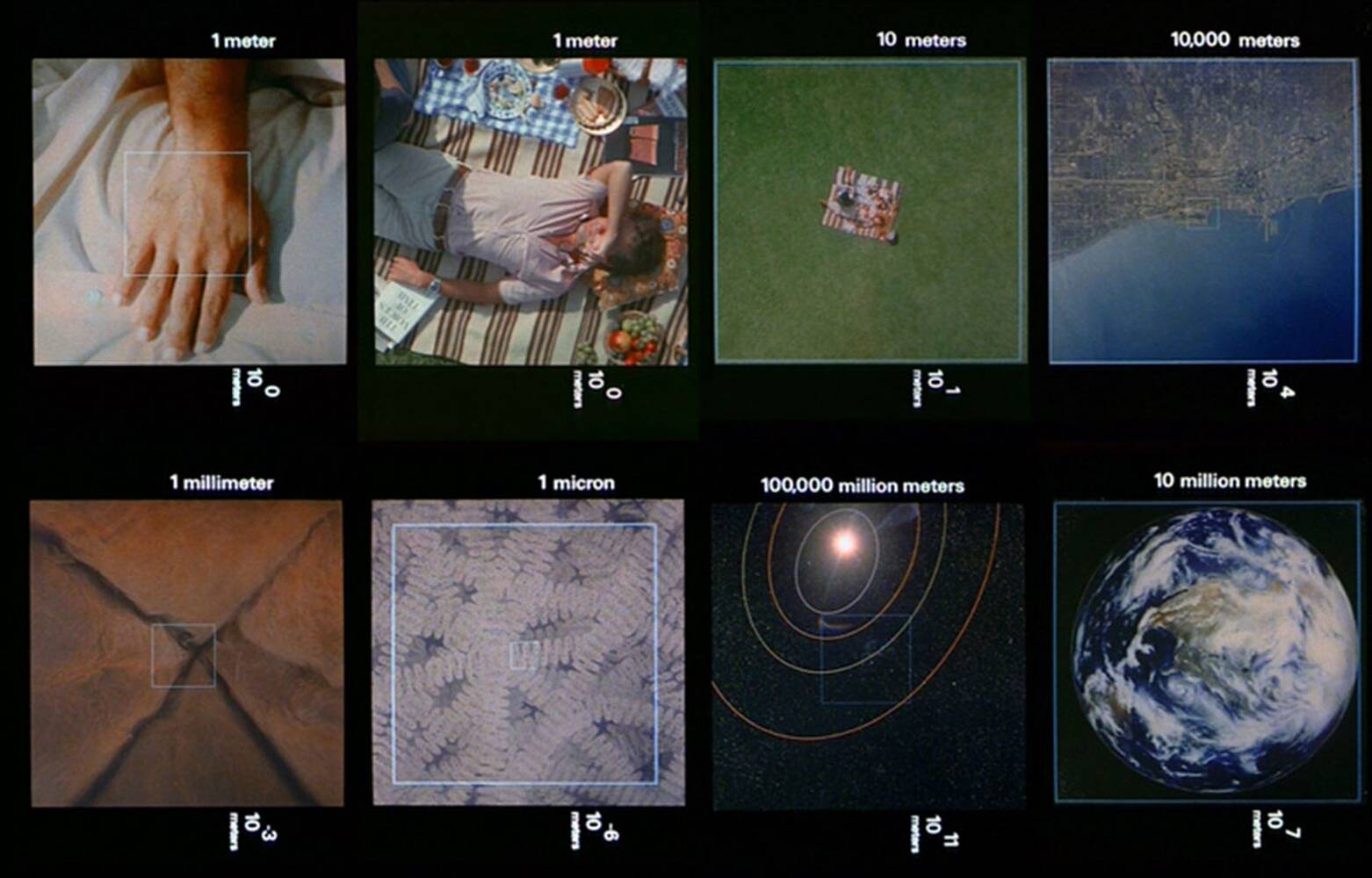

Although the controversial complex maritime claims and their geo-political dramas about sea trade, oil reserves, and fish stocks are often the primary focus of global attention with respect to the South China Sea, the South China Sea is suffering. In recognition of the environmental suffering of the South China Sea, the “South China Sea Monument” is a reclamation of the sea for the common good and for present and future generations.

The South China Sea is a semi-enclosed sea that is located along the path of the ancient Maritime Silk Road. It is presently the world’s busiest floating trade network. In recent years, it has been the site of episodic military disputes, particularly concerning the transformation of islands into permanent naval bases. Observing countries erecting new sea boundaries, instead of effectively managing and protecting maritime space, together with maritime lawyer Agnes Chong and geographer Eric Laflamme, we propose the establishment of a legal framework and a series of maps to define an extra-territorial marine protected area (MPA). This MPA would be managed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) for the protection of marine biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdictions.5

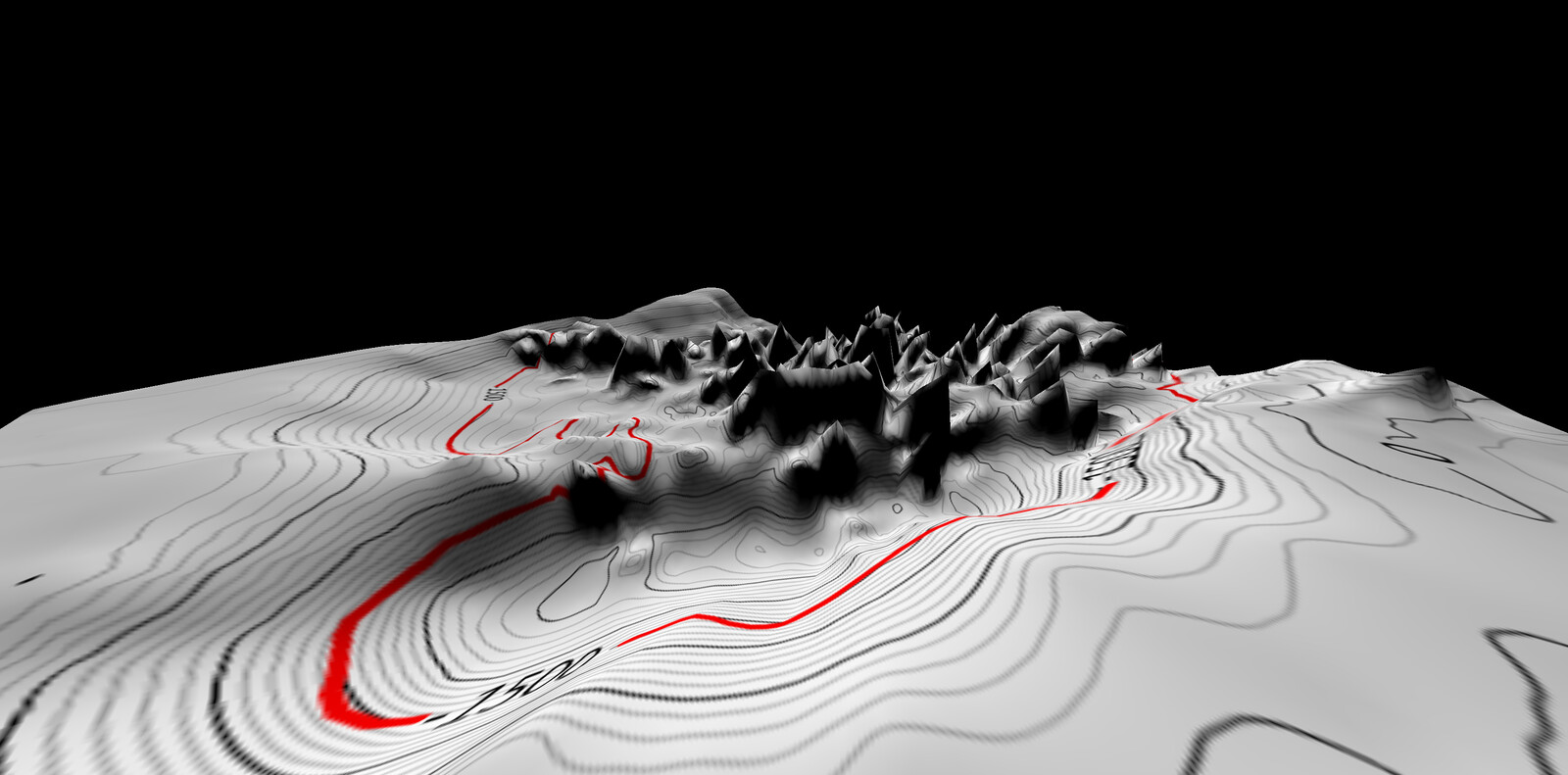

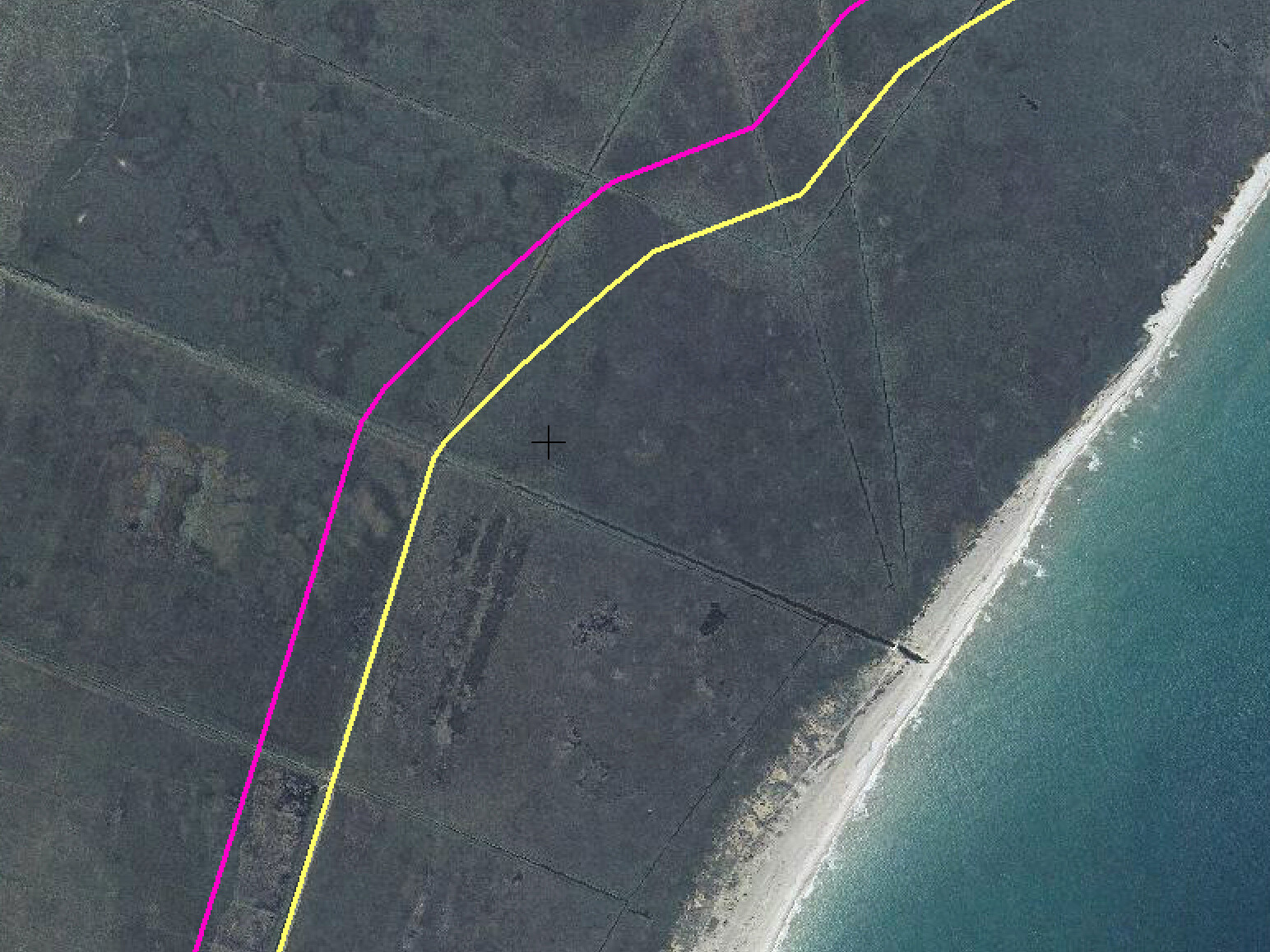

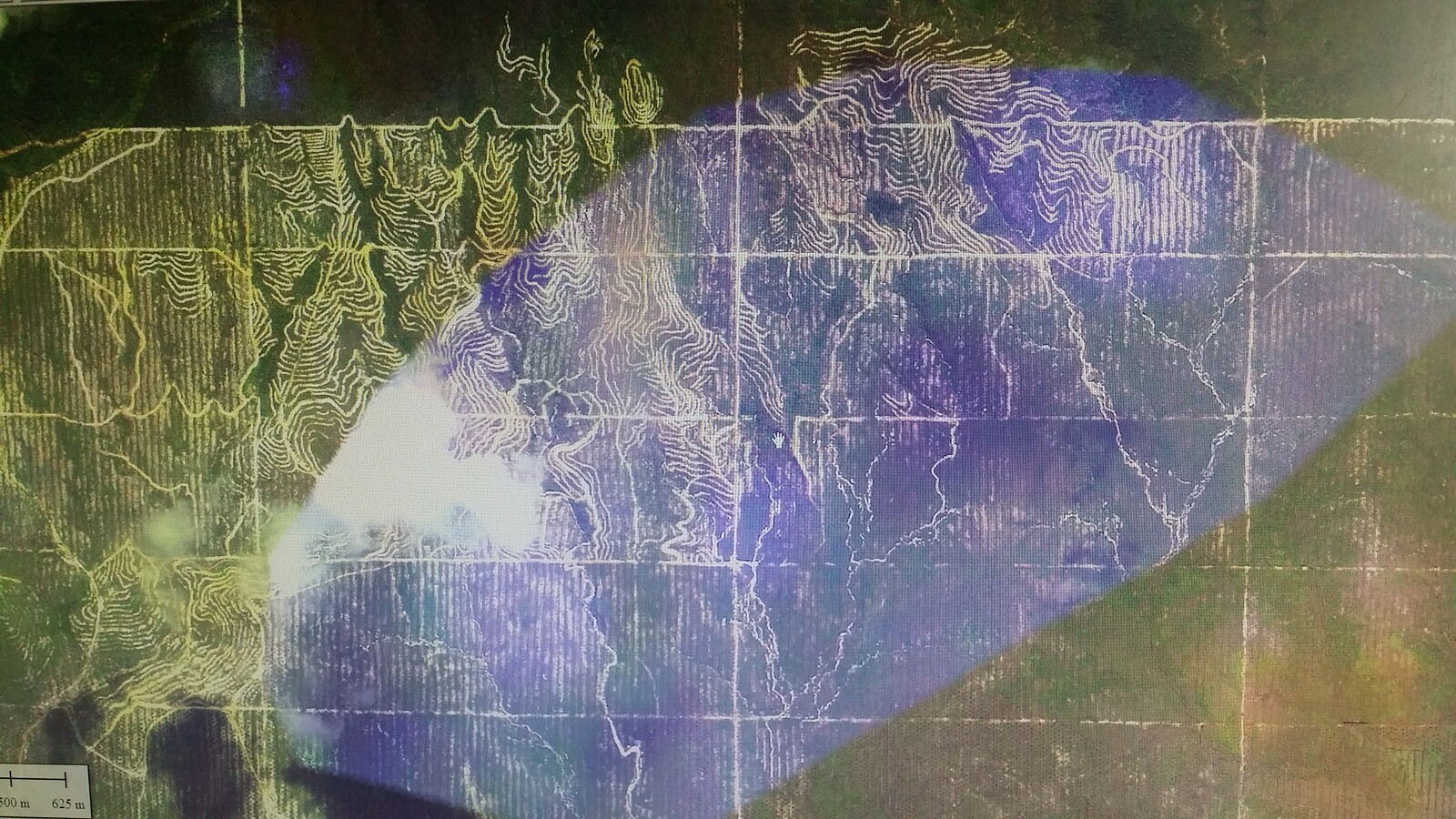

MAP Office, Liquid Land | Solid Sea, 2017.

1. The Sea (2D)

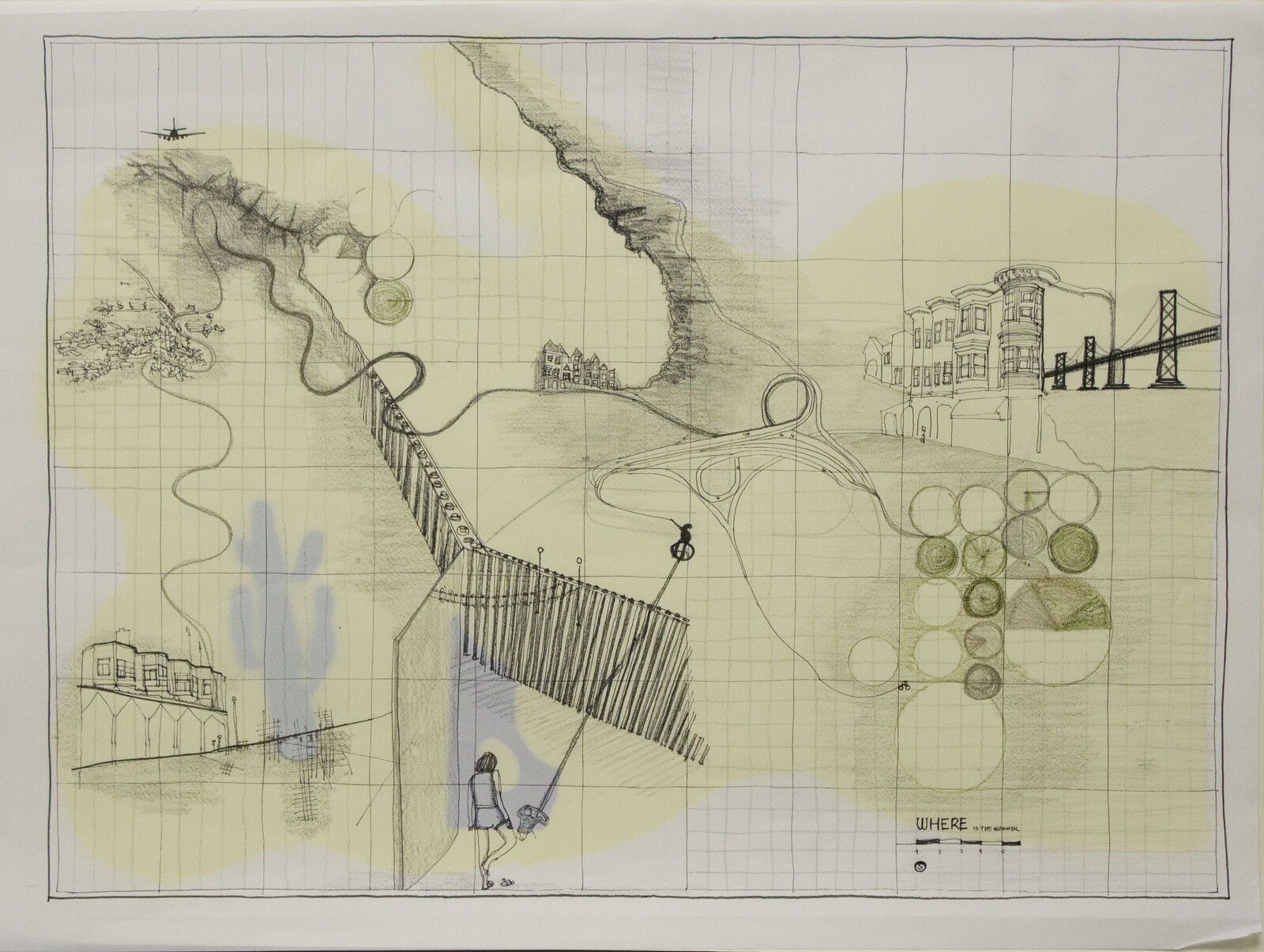

The “South China Sea Monument” is a collection of maps and drawings retracing the natural “islands, islets, rocks, reefs, low-tide elevations and submerged features.”6 The criteria by which these are selected is based on their geology/landform, climate/hydrology, and ecology/biogeography, as well as their interactive land/sea relationship. Also influencing the collection is the narrative of the oceans as a “global commons” within international law.

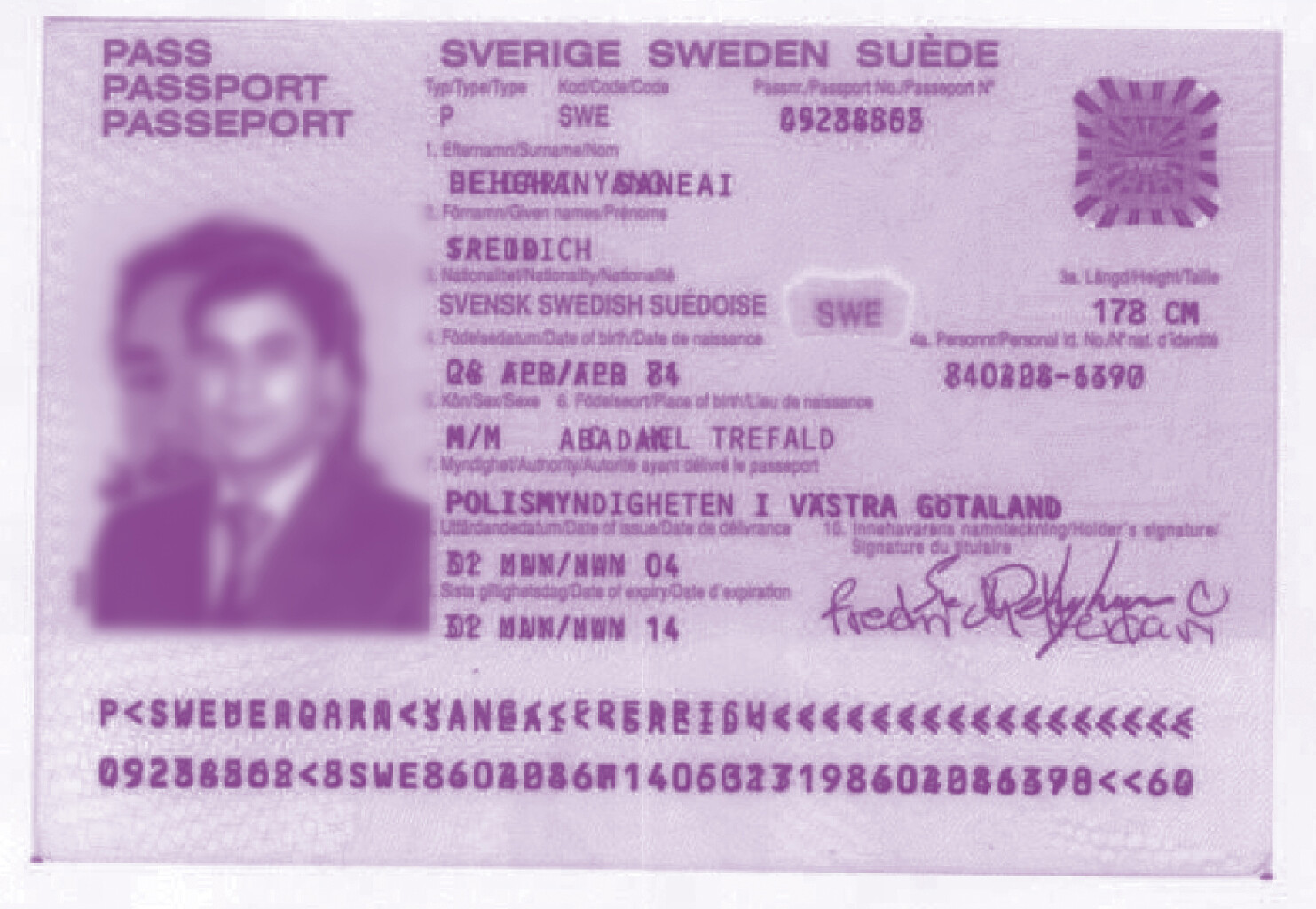

Maps, sovereign markers, and official names represent solid evidence of a territorial claim. However, the authority of such documents can be contested when they overlap with independent evidence from different countries and over centuries.

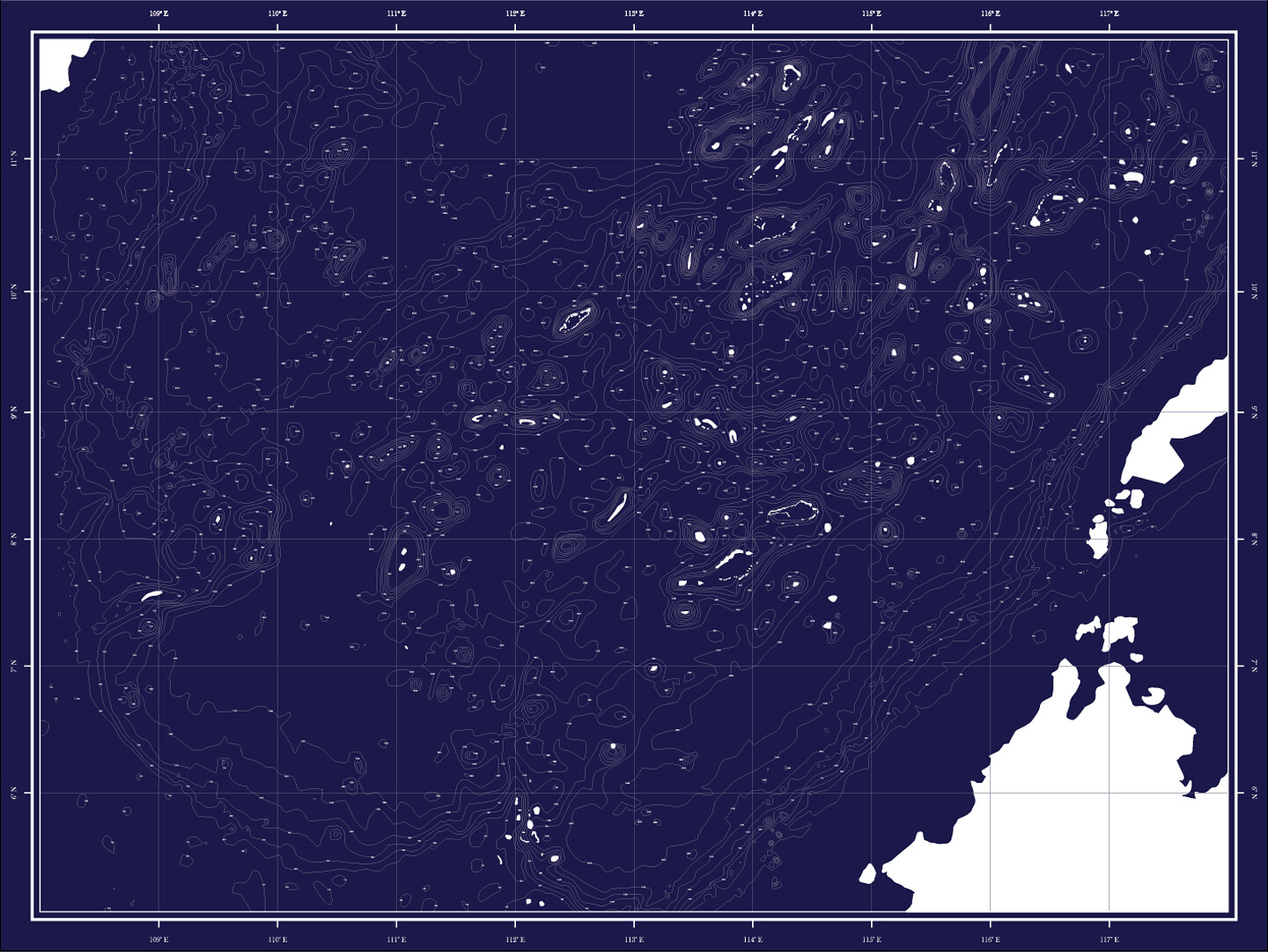

Mapping the South China Sea is not an easy task. Wikipedia claims that it “contains over 250 small islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs, and sandbars, most of which have no indigenous people, many of which are naturally under water at high tide, and some of which are permanently submerged.”7 We began by creating a database to organize the name and location of each atoll, island, shoal, bank, cay, reef, and rock above sea level. Using old maps from different sources and origins, as well as online open sea maps and charts that are updated daily, we were able to identify 166 features for the Spratly Islands, forty-two for the Paracel Islands, and three for the Scarborough Shoal.

Another challenge is that there are many different names given to the South China Sea’s features, which points to the region’s complex colonial past. The Board of Geographic Names (BGN) serves as evidence of widespread English usage, although most features have specific names in Chinese, English, Filipino, French, Malay, and Vietnamese, as well as names given by fisherman that describe the shape of the perimeter of the island. One example of this is Spratly Island (BGN), also named Storm Island in English, 南沙群岛 (Nan Sha Qun Dao) in Chinese, Dao Truong Sa in Vietnamese, Lagos in Malay, and Ilot de la Tempete in French. Place names are fluid and continue to be an issue in current disputes. In 2017, Indonesia became a seventh claimant of the South China Sea by naming the water north of Natuna Island the North Natuna Sea, and publishing a new map of the territory.8

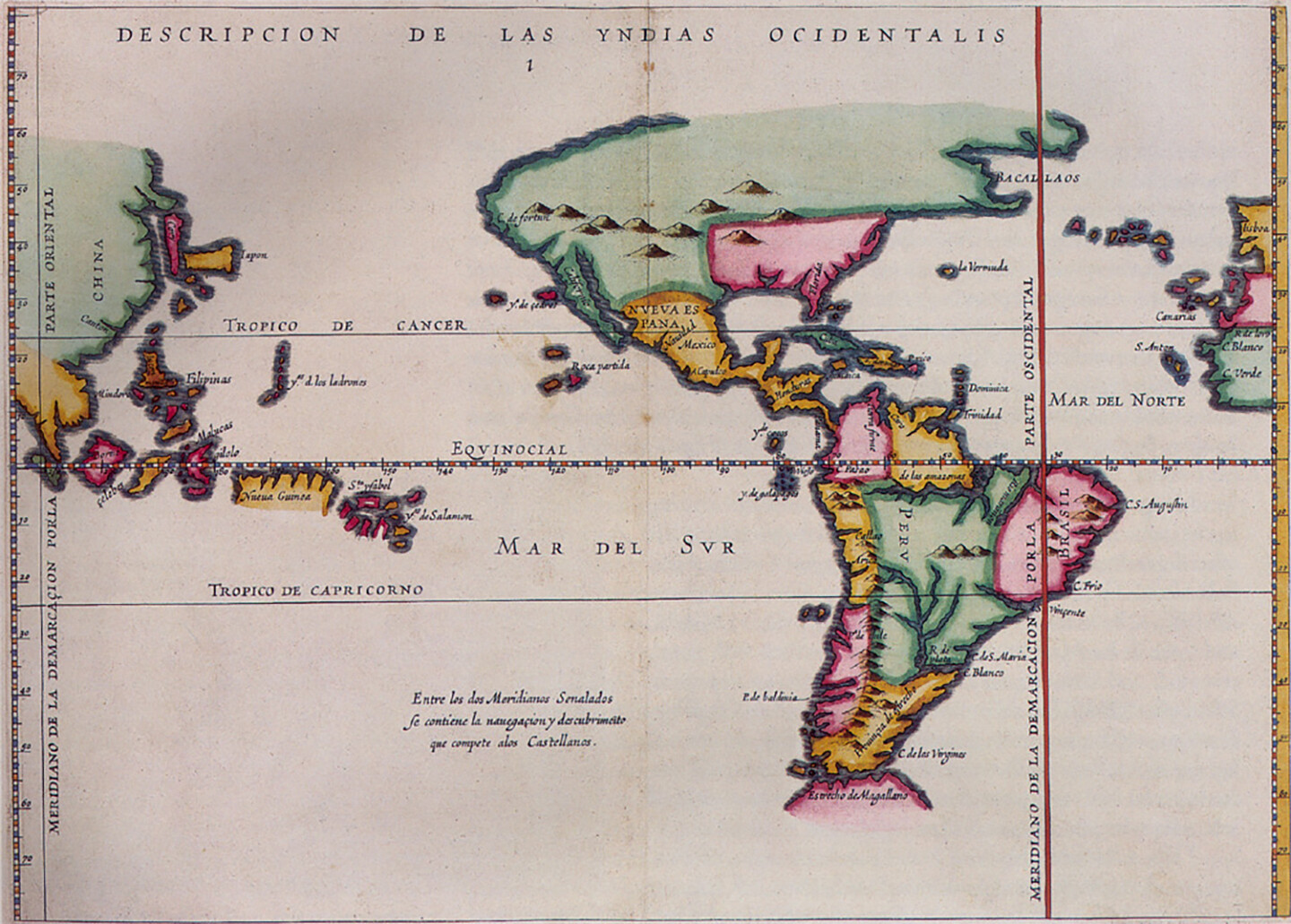

Territorial boundaries are contentious in international politics. Historical sovereignty and “the acquisition of territorial rights” in Europe was established in the sixteenth century by the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and France in their race with Spain and Portugal to become global superpowers. China accepted the principle of “historical title” with respect to the Paracel and the Spratly islands in 1876 to prove they were discovered in the second century BC by Chinese ships.9 China’s ambassador to England made the country’s first formal sovereignty claim in 1876. However, this claim did not stop British troops from destroying small camps on islands in the South China Sea and claiming a large part of this territory for themselves. France adopted this same practice in 1933, followed by Japan who began to station troops on some of these islands in 1939.

The superposition of territorial maps onto the South China Sea has continued to evolve since World War II and the incursion of the United States into the region. Since then, peace relies on “the absence of any clear grand strategic coherence or orderliness in the way South East Asians and extra regional powers manage the security of the region.”10 This explains the recurring maritime and airborne military tensions in the Sea between Beijing and Washington, which impacts the neighbouring littoral states as they struggle to keep their own interests safe. The region boasts one third of the world’s shipping traffic and twelve percent of the global fish catch. These industries are of vital importance to the economies of the claimant states and therefore, require protection.

The South China Sea boasts the world’s fourth largest annual marine production.11 However, the Sea is overfished, and unsustainable fishing practices have led to adult fish disappearing from the area. In addition, fishing methods destroy coral reef fish habitats.12 Furthermore, the busy shipping routes in the South China Sea have had detrimental effects on the native flora and fauna and cause environmental pollution.13 The construction of artificial islands in the Spratly and Paracel Islands has led to diseases in fish colonies and has affected other marine life, including fish, sea turtles, and sea mammals.14 In the Spratly Islands, aggressive fishing and giant clam harvesting has impacted the coral reef habitat, where it is estimated that it will take at a decade to get back to at least 60% coral cover.15 In turn, damaged coral reefs endanger fish stocks, putting approximately 270 million people at risk of food insecurity. Of these, more than 127 million live in rural areas and 38 million live in poverty.16

2. The Islands (2.5D)

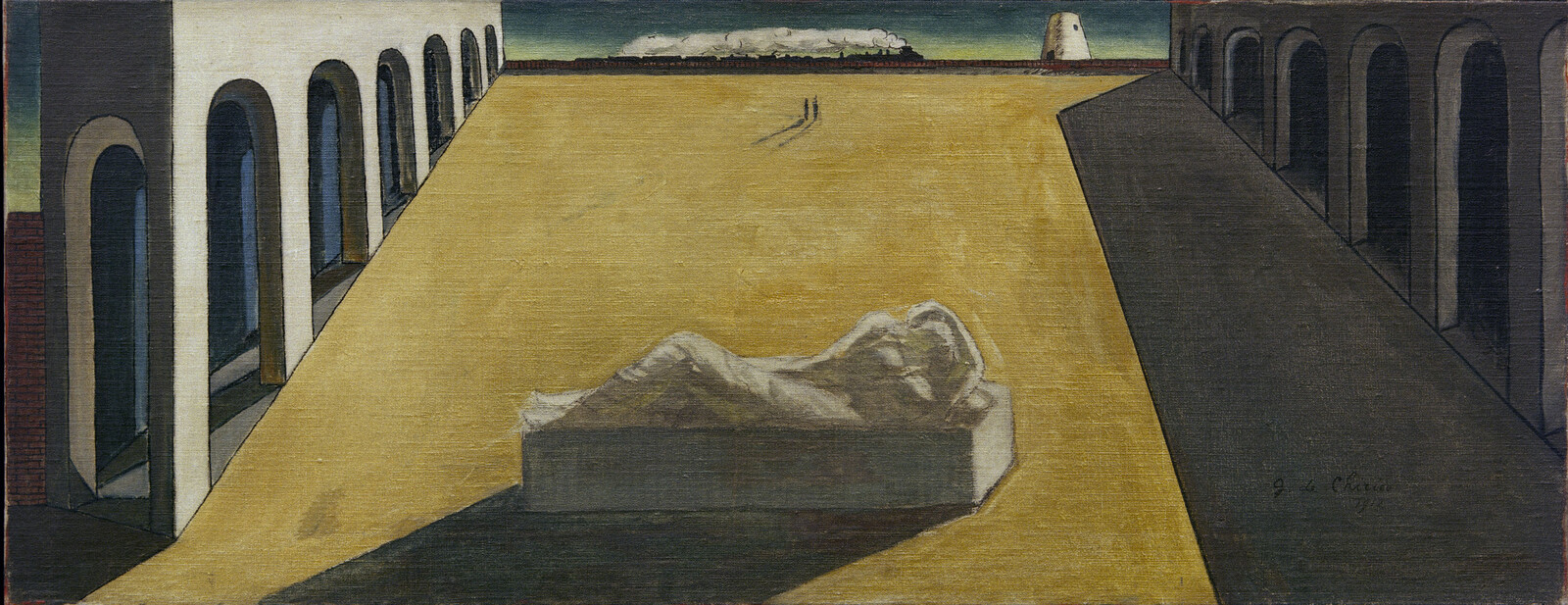

The South China Sea lies above a drowned continental shelf. This sub-marine shelf is compressed, forming a myriad of tectonic extrusions that oscillate between very shallow water to deep canyons and trenches. On the surface, necklaces of small islands, sand banks, and rocks outline the atolls. Their elevation depends on the tides and the storms that temporarily submerge the flat islands. Together, they form large archipelagic groups defined by what countries they are and are not claimed by.

Our attention is further grabbed by the contestation of this highly prized maritime space. The South China Sea is, and continues to be, an immensely contested maritime space, fought over by between the six states that surround it. Six states around whom the South China Sea encompasses. The three main archipelagos are the Pratas Islands, Paracel Islands, and Spratly Islands. In addition, the two large submerged features—Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Shoal—are contested.17 The archipelagos consist of “small islands, islets, rocks, reefs, low-tide elevations, and submerged features.”18 The Spratly Islands are contested by China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei.19 The Paracel Islands are disputed by China, Vietnam, and Taiwan.20 Scarborough Shoal is contested by China, Taiwan, and the Philippines.21 The Pratas Islands and the Macclesfield Bank are claimed by China and Taiwan.22

At low tide, reefs emerge one or two meters above water, and except for Ganqan and Pagasa Island, none of the islands have a fresh water supply or top soil. The question is therefore whether they should be considered by law as islands at all, or rather as something neither land nor sea.23 An international tribunal did state, after all, that artificial islands don’t have the same legal rights than those given to natural islands.24

Starting in the 1970s, tiny sand bars throughout the South China Sea were occupied by various countries with watchtowers and a few soldiers in rotation to create basic military outposts. Some were weak bamboo stilt structures, while others were solid octagonal concrete pillboxes of a few hundred square meters. The lagoons surrounding the sand bars provided fish as needed for a small group of military personnel to survive for a few months.

The Philippines was the first country to initiate a military occupation to back its territorial claim. Their marine guard operated from the US Navy World War II ship Sierra Madre. After more than twenty years of service, however, the ship was a grounded on the reef in 1999. It is still today used as a rust-eaten base for watching over the Second Thomas Shoal.25

In the meantime, the Vietnamese outpost directly anchored to an oil rig to mark their occupation. This was a pragmatic option, quickly deployable to create a network of surveillance stations around Vietnam’s maritime border. Up until 1987, the Spratly Islands were claimed by Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines.26

Malaysia made its first move on the South China Sea in 1983, when the Royal Malaysian Navy set up a base at Swallow Reef / Pulau Layang Layang. Beginning with a small encampment for eighteen Special Forces and a helipad, the island was developed into a tourist spot in 1989. To this date, it is the only military base accessible to the public. It is open six months a year to expert divers, during the hammerhead shark-mating season. The operation of the half-military base, half five-star resort is hazardous to the island and the tourists alike. On a research visit, the manager of the hotel informally suggested to us that the tourists protect the island from hostile foreign military forces.

Progress with respect to the Sea’s geo-strategic potential and increase in military occupation occurred in January 1988 with the construction of China’s first oceanic observation stations: three along the coast, one in the Paracels, and one in the Spratlies at the Fiery Cross shoal. This initiative responded to a request by UNESCO as part of a Global Sea Level Observing system.27 Historical footage from March 14, 1988 shows the first armed clash between China and Vietnam at the Johnson Reef. During the time of what was later called the “1988 Invasion,” China seized Subi Reef from the Philippines to erect the first military and radar structure in the area.

In last ten years, China has begun to reclaim massive amounts of land on Eldad reef. Along with other strategic features, they have gradually created state-of-the-art, military islands. This development has given visibility to a conflict that has been taking place for last thirty years. From then on, the South China Sea has frequented news headlines. From this deluge of information, we were able to put together an atlas, which contained identificatory information about each of the Sea’s 170 features, and extended historical data for its 65 occupied territories.

3. The Deep (3D)

The marginal basin is a subduction zone where tectonic plates meet. With an average depth of 1,200 meters, the undulating seabed bathymetry forms a complex ground that produces strong underwater currents and surface waves. Over the last twenty years, several international expeditions have conducted scientific drilling and seafloor observation. Performant deep submersible vehicles took samples of fauna, flora, water, and sediments at depths up to 7,000 meters. These deep-sea ecosystems are unique biological communities, the study of which contributes to a deeper understanding of global environmental changes.

So far, the South China Sea’s trenches and seabed have mainly been explored for scientific purposes. However, untapped oil and gas reserves are the source of escalating tensions, with drilling companies from the United States partnering with regional allies in joint projects.

South China Sea’s suffering is a story of exploiting the sea for its wealth while ignoring the harm caused to its marine biological diversity. Each year, US$5.3 trillion worth of goods are transported through the sea lanes of the South China Sea (of which the US trade accounts for US$1.2 trillion).28 There are proven reserves of 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, as well as undiscovered reserves that amount to (a minimum of) 12 billion barrels of oil and 160 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.29 And fisheries in the South China Sea comprise 12% of the total global catch, accounting for US$21.8 billion in 2012.30 This all does not even account for the effect of the US dollar on the economies in the region, as well as the value of the 16 trillion cubic feet of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) per annum that passes the South China Sea, which amount to half of the global LNG trade.31

Today’s territorial disagreement is not just over oil, gas, and fisheries, but sunken cultural heritage, mostly shipwrecks. Since 1980, illegal activities at sea have endangered or destroyed many sites and artefacts.

4. The Law (4D)

The South China Sea is a continuing challenge to international law and the arbitration of maritime legal questions. What has been labelled the “Asean Way” is an anti-legalist attitude with a propensity to avoid resolving conflict in the region.32 A recent confirmation of this was in 2016, when China refused to participate in discussions with the Philippines at the Permanent Court of Arbitration. With nations refusing to sit at the same table where issues of sovereignty are at stake, it is hard to believe that parties will abandon their claims.

Current threats in the Pacific require new forms of protection to preserve both lasting peace and the ocean.

There are currently insufficient efforts to preserve and protect the environment of the South China Sea. Oil exploration, land reclamation, large-scale fishing, and navigation activities have seriously damaged the environment of the South China Sea.33 Both coastal and non-coastal states have an obligation to preserve and protect the environment of the seas in the course of their use of the same seas.34 However, we know that states are failing in their environmental protection obligations.35 For example, to avoid the continuing damage to marine life in the South China Sea, land reclamation activities need to be preceded by environmental impact assessments.36 This protection would be best accomplished through collaboration between states, rather than through the responsibilities of individual states. Unilateral activities that are harmful to the South China Sea need to cease in order to allow the South China Sea to recover.37 The 2012 UN conference on sustainable development agreed that states need to carry out their environmental obligations to protect the global environment for the present and future generations.38 On this basis, there needs to be an environmental impact assessment of activities in the South China Sea and focus placed on the common good.39 In this regard, claims and claim-supporting activities need to be significantly curtailed. The South China Sea should be an international peace park in order to protect the marine life therein.40

Among the noise of these territorial conflicts, the sea is suffering.41 If the sea had a voice, what would it say? Judging by what we know about the extent of environmental damage to the South China Sea, we can only imagine. But we can look at the indicators by scientific professionals who warn us to reduce and find sustainable alternatives for our continued activity. Otherwise, we might reach a point where it is no longer possible to heal, and where our only fate is extinction.42

Clive Schofield, Understanding Competing Maritime Claims in the South China Sea in the South China Sea Dispute (ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2016), 22.

Hayley Roberts, “Current Legal Developments South China Sea, Responses to Sovereign Disputes in the South China Sea,” The International Journal of Marine and Coastal Law 30 (2015): 199–211, 199.

Schofield, Understanding Competing Maritime Claims, 22.

Shen Dingli, Elizabeth C. Economy, Richard Haass, Joshua Kurlantzick, Sheila A. Smith, and Simon Tay, “China’s Maritime Disputes,” Council on Foreign Relations, ➝.

Schofield, Understanding Competing Maritime Claims, 23.

“South China Sea,” Wikipedia, ➝.

Aaron L. Connelly, “Indonesia’s new North Natuna Sea: What’s in a name?,” The Interpreter, July 19, 2017, ➝.

Xuechan Ma, “Historic Title Over Land and Maritime Territory,” Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies 4, no. 1 (Winter/Spring 2017): 31–46, ➝.

Amitav Acharya and See Seng Tan, “Betwixt balance and community: America, ASEA, and the security of Coutheast Asia,” International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 6, no. 1 (2006): 40.

John W. McManus, Kwang-Tsao Shao, and Szu-Yin Lin “Toward Establishing a Spratly Islands International Marine Peace Park: Ecological Importance and Supportive Collaborative Activities with an Emphasis on the Role of Taiwan,” Ocean Development and International Law 41, no. 3 (July 2010): 273.

Ibid.

Ibid.

John W McManus, “Offshore Coral Reefs and High-Tide Features of the South China Sea: Origins Resources, Recent Damage and Potential Peace Parks,” in Murray Hiebert ed., In the Wake of the Arbitration: Papers from the Sixth Annual CSIS South China Sea Conference (CSIS Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2017), 137–139.

Ibid., 141–142.

Ibid., 124, 142.

Kun-Chin Lin and Andres Villar Gertner, Maritime Security in the Asia-Pacific, China and the Emerging Order in the East and South China Seas (Chatham House, The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2015), 6.

Schofield, Understanding Competing Maritime Claims, 23.

McManus, Shao, and Lin, “Toward Establishing a Spratly Islands International Marine Peace Park”: 271.

Lin and Villar Gertner, Maritime Security, 5.

Ibid.

Raul Pedrozo, “China Versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea,” CNA Occasional Paper, August 2014, 1.

This question is the key to the Philippines’ case against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague: Is Itu Aba an “island” or “rock” under Article 121(3) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)?

Christopher Mirasola, “What makes an Island? Land reclamation and the South China Sea arbitration,” Asia Maritime Transparence Initiative, July 15, 2015, ➝.

Brought to the United States Navy in 1970s, the Philippine military deliberately grounded the ship atop the reef in 1999. “Philippines repairs crumbling South China Sea ship outpost,” AFP, July 15, 2015, ➝.

Peter Kreuzer, “A Comparison of Malaysian and Philippine Responses to China in the South China Sea,” The Chinese Journal of International Politics 9, no. 3 (Autumn 2016): 239–276.

Lingqun Li, China’s Policy towards the South China Sea: When geopolitics meets the Law (New York: Routledge, 2018).

Lin and Villar Gertner, Maritime Security, 5.

Ibid.

Michael Fabinyi, “The Destruction Beneath the Waves of the South China Sea,” Asia & the Pacific Policy Society, July 30, 2016, ➝.

Ian Storey and Cheng-yi Lin eds., The South China Sea Dispute: Navigating Diplomatic and Strategic Tensions (ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2016), 4.

Nicole Jenne, “Managing Territorial Disputes in Southeast Asia,” Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs 36, no. 3: 35–61.

Nguyen Chu Hoi and Vu Hai Dang, “Environmental Issues in the South China Sea: Legal Obligation and Cooperation Drivers,” International Journal of Law and Public Administration 1, no. 1, June 2018.

Article 56 and 58 of United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

PCA, South China Sea Arbitration between the Philippines v China, Award, July 12, 2016; and Chloe Houdre, “Environmental Ramifications of the South China Sea Conflict: Vying for Regional Dominance at the Environment’s Expense,” Georgetown Environmental Law Review, July 12, 2018, ➝.

Abhijit Singh, “Why the South China Sea is on the Verge of an Environmental Disaster,” The National Interest, August 13, 2016, ➝.

United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, Rio+20, The Future We Want, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, June 20–22, 2012.

Ibid.

Ibid.

McManus, Shao, and Lin, “Toward Establishing a Spratly Islands International Marine Peace Park”: 146.

Marie Antonette Juinio-Meñez, “Biophysical and Genetic Connectivity Considerations in Marine Biodiversity Conservation and Management in the South China Sea,” Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy 18, no. 2 (2015): 110–119, 113.

Ibid.: 117–118.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.

Category

Subject

All extended quotes in this text are fragments of a legal text written in collaboration with maritime lawyer Agnes Chong.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.