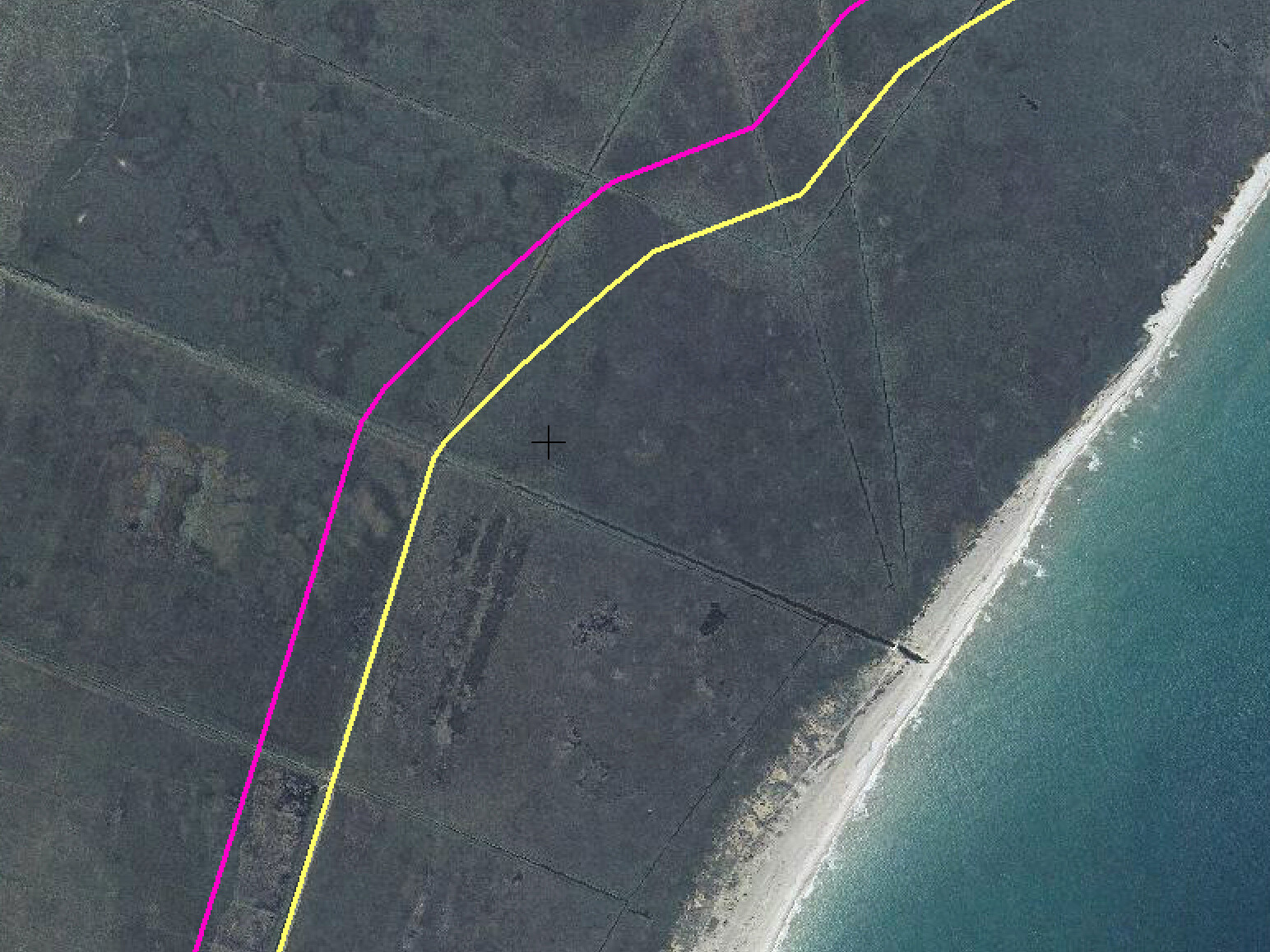

In early March 2020, the Turkish government found itself stuck in a military conflict with Russia in Idlib, a border city in northwest Syria. The conflict caused a large number of Syrians to flee to the north, into Turkey’s southernmost province. In an attempt to force the EU and NATO to support Turkey’s military operation in Syria, the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan opened his country’s northwestern borders to Greece and encouraged tens of thousands of migrants and refugees to cross into Europe. On the other side, Greek border guards used brutal methods to push back border transgressors. Both types of border operations—crossing one (invading Syria) and opening another (to Europe)—worked to reinforce Turkish nationalism.

At the same time, Jimmie Åkesson, leader of Sweden Democrats—the second largest political party in Sweden that has roots in Swedish Nazi movements and runs on a radical anti-migrant platform—travelled to the Greece-Turkey border and handed out flyers to migrants and refugees with the message: “Sweden is full. Do not come to us… Sorry about this message.” While he was doing this on the ground, thousands of kilometers away from Sweden, colleagues from his party campaigned on social media with the message “hold the border” (Håll gränsen), which with the proliferation and escalation of racism throughout Europe, serves to increase the party’s popularity and votes. Both opening and crossing borders (Turkey), as well as holding them closed (Sweden) can serve to reinforce nationalism and national identities.

In his seminal work on the national imaginary, Benedict Anderson writes about the magical function of nationalism in turning “chance into destiny.”1 The geographical “accident” of being born on one side of a border or another can determine one’s access to or lack of rights, security, and resources. The Swedish politician’s attempt to “hold the border” against migrants was an attempt to guard this magical function. Magic changes our perceptions of the real: something turns into something else. Like magic, borders engender new perceptions. Borders turn neighbors into enemies. A short distance suddenly becomes farther. The skin of people on the other side becomes darker. Nomadic tribes become illegal border crossers. Cousins from the next village become illegal transgressors. Traders become smugglers. The value of commodities increases and decreases.2

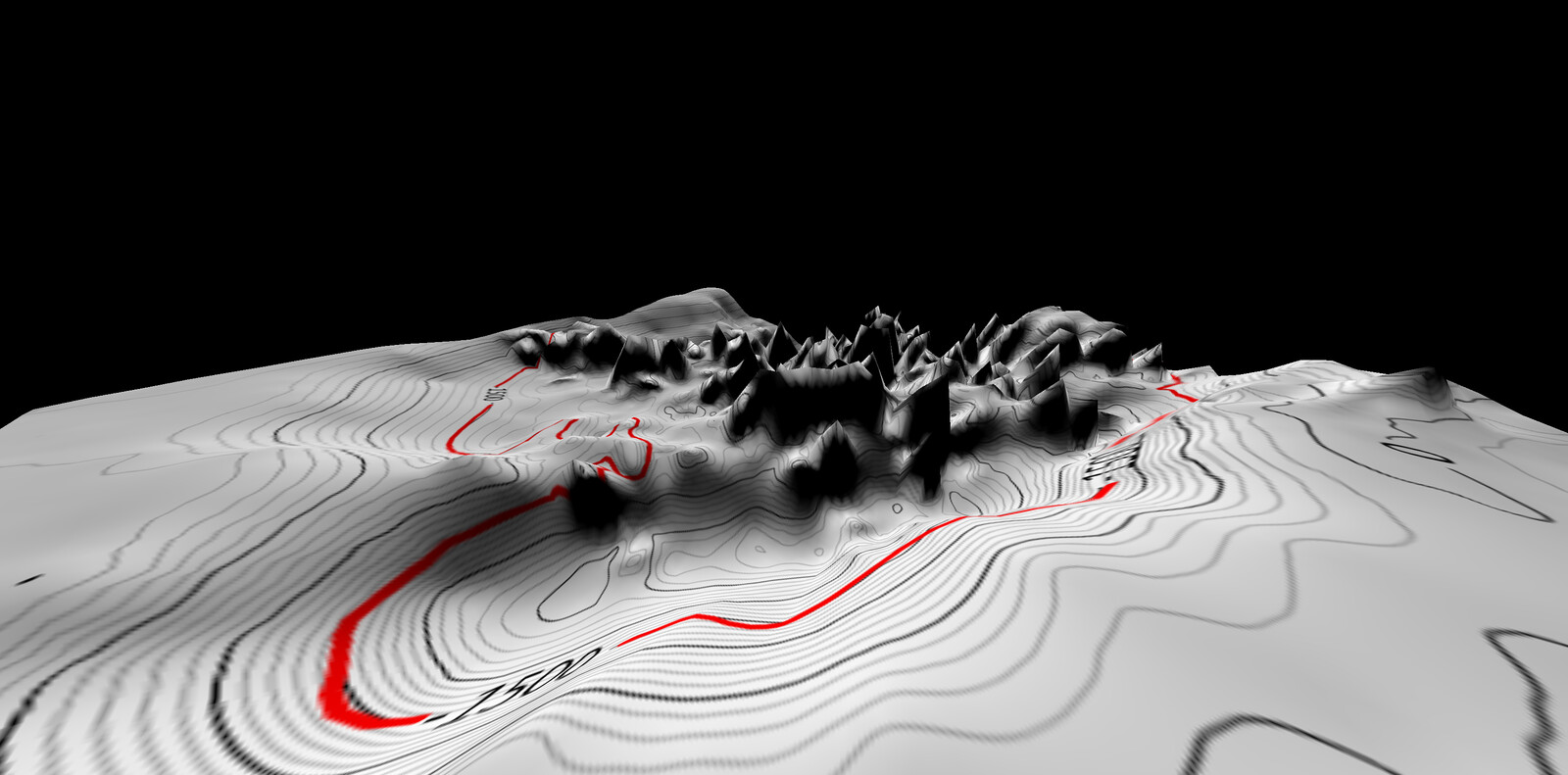

Magic works by controlling what a spectator sees. In 2019, a Russian man was arrested for building a fake border post in the forest near the Russia-Finland border and taking money from migrants who believed they would be crossing into Finland, when in fact, on the other side, they would still be in Russia. What the con artist did here was nothing exceptional. He did what usually states do: he drew a line that did not exist before, set up a checkpoint, and persuaded people on the move to believe that the line drawn was real. Like with magic, being able to control the position from which one encounters a border often places it out of reach. When you think you have realized or reached the border, it is somewhere or something else. The border is always ahead of you. Its form and shape constantly shift. Its place stretches; its time expands. It moves across city life, the countryside; it cuts through schools, public squares, and hospitals.

Similarly, the magic of the border can turn anyone into a border guard: an employer, a landowner, a teacher. Regardless of their officiality, border guards claim to have legitimate reasons to stop and interrogate those whose bodies do not match the image of legalized mobile bodies. Borders appear wherever and whenever deemed necessary: as a security measure, as a sign of greatness, or not least as a caring arrangement. Borders today are said to be built out of love, not hate. The far-right Swedish Democrats party, for instance, has achieved electoral success with the slogan of love (to Swedes) rather than of hate (towards non-Swedes). Trump justifies his new wall as a sign of love and care; “to save lives.”

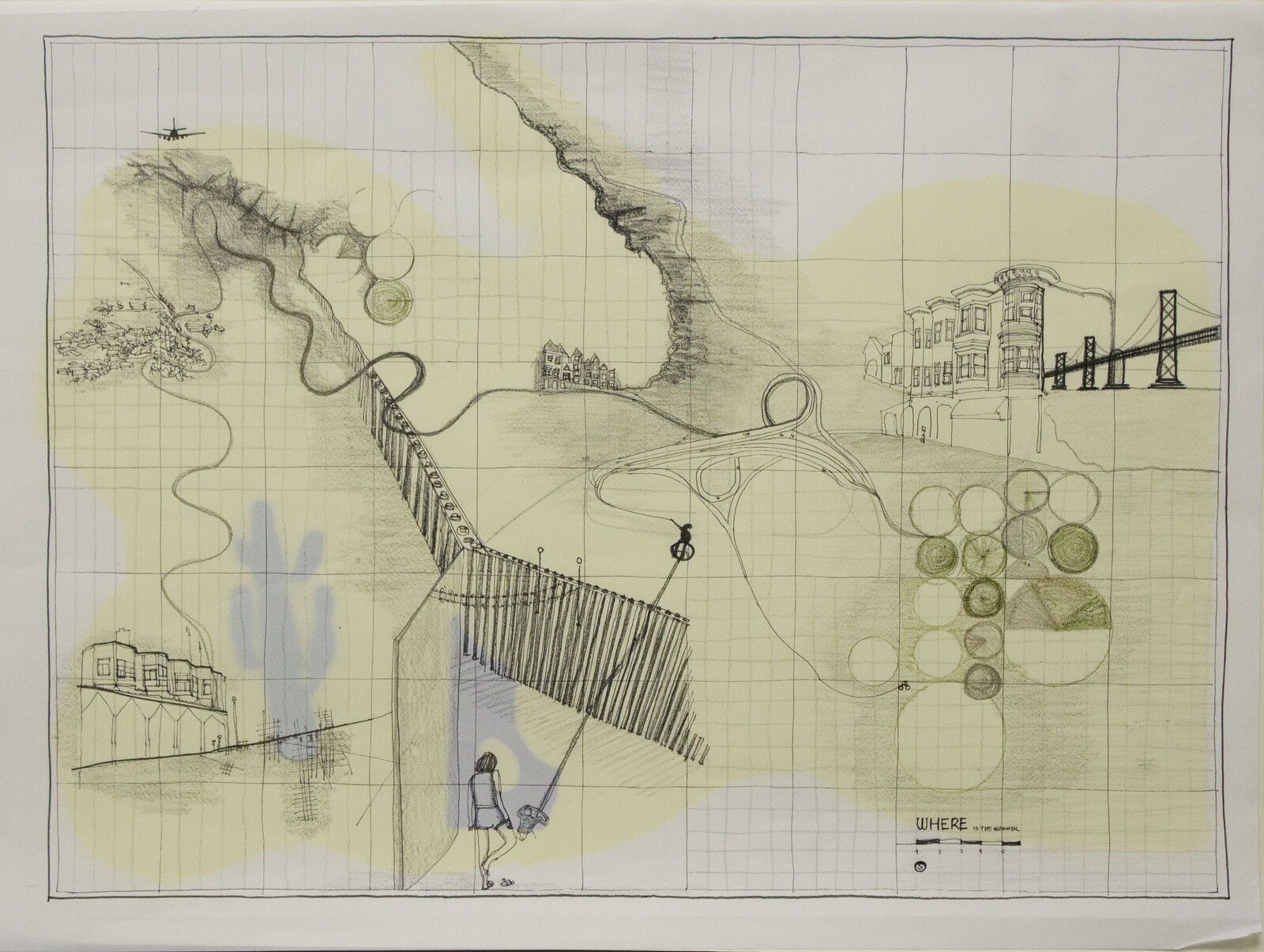

The magic of borders makes us see hate and believe it is love. This power is best seen when borders are designed. Miami-based DOMO Architecture + Design’s project of “Beautifying the Border,” for example, which was formulated in response to Trump’s call for “a beautiful wall,” sought to “[manipulate] all manmade fences or walls that create an aggressive division between both countries by means of design… By removing the idea of a wall or a fence, we remove the negative social, cultural and physical connotations associated with visual and physical barriers.”3 With about 750,000 unused shipping containers, the designers want to make the violence embedded in the border invisible while maintaining existing power relations. While the “ugliness” of the border barrier is concealed, its brutality is still in place.

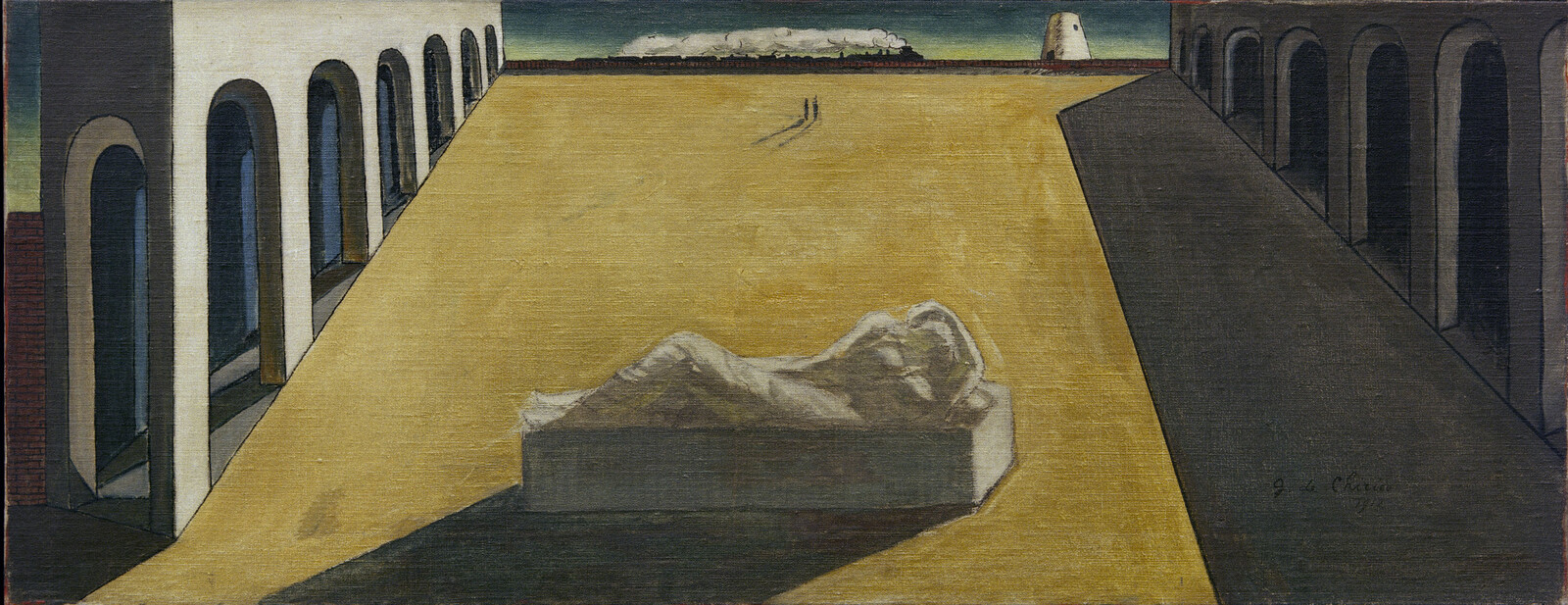

Beautifying the violence of the border is nothing new. Indeed, has long been part and parcel of nationalist projects. Take Terezín, for example. This transit concentration camp organized by Nazis in the occupied Czechoslovakia during World War II was a temporary hub for keeping deportees before distributing them to other concentration camps across occupied eastern Europe. In June 1944, the International Red Cross was allowed into the camp. Before the visit, however, the Nazis intensified deportations to empty the overcrowded camp, and changed street signs from numbers to names. During the visit, a full week of activities was staged: a Jewish cultural week with theater and music, urban gardening, sports matches, competitions, and so on. Terezín performed the magic of what Nazis called “the beautification of the camp” (Verschönerung). It was meant to assure the international community that it was not a concentration camp or a ghetto, but a town for productive life and labor. They even claimed that it gave elderly Jews the opportunity of a “safe retirement in a spa town.”

Film still of the 1944 propaganda film “Terezin: A Documentary Film from the Jewish Settlement Area,” showing what was narrated as inmates active on the farm, producing food for themselves.

By assembling materials, images, discourses, and resources into forms that do not exist before, borders appear as naturalized and timeless. By rendering the histories and politics behind them invisible, borders even emerge as beautiful and normal. What materialization does here, be it through fortification, visa procedures, military operations, propaganda, or humanitarian engagements, is to configure a single space and time for some as one of control, and for others as one of care. With its active production of binaries, this demarcation is part of classificatory practices of western modernity, in which people, places, and times are “defined by [their] diametrically opposed difference from the other.”4

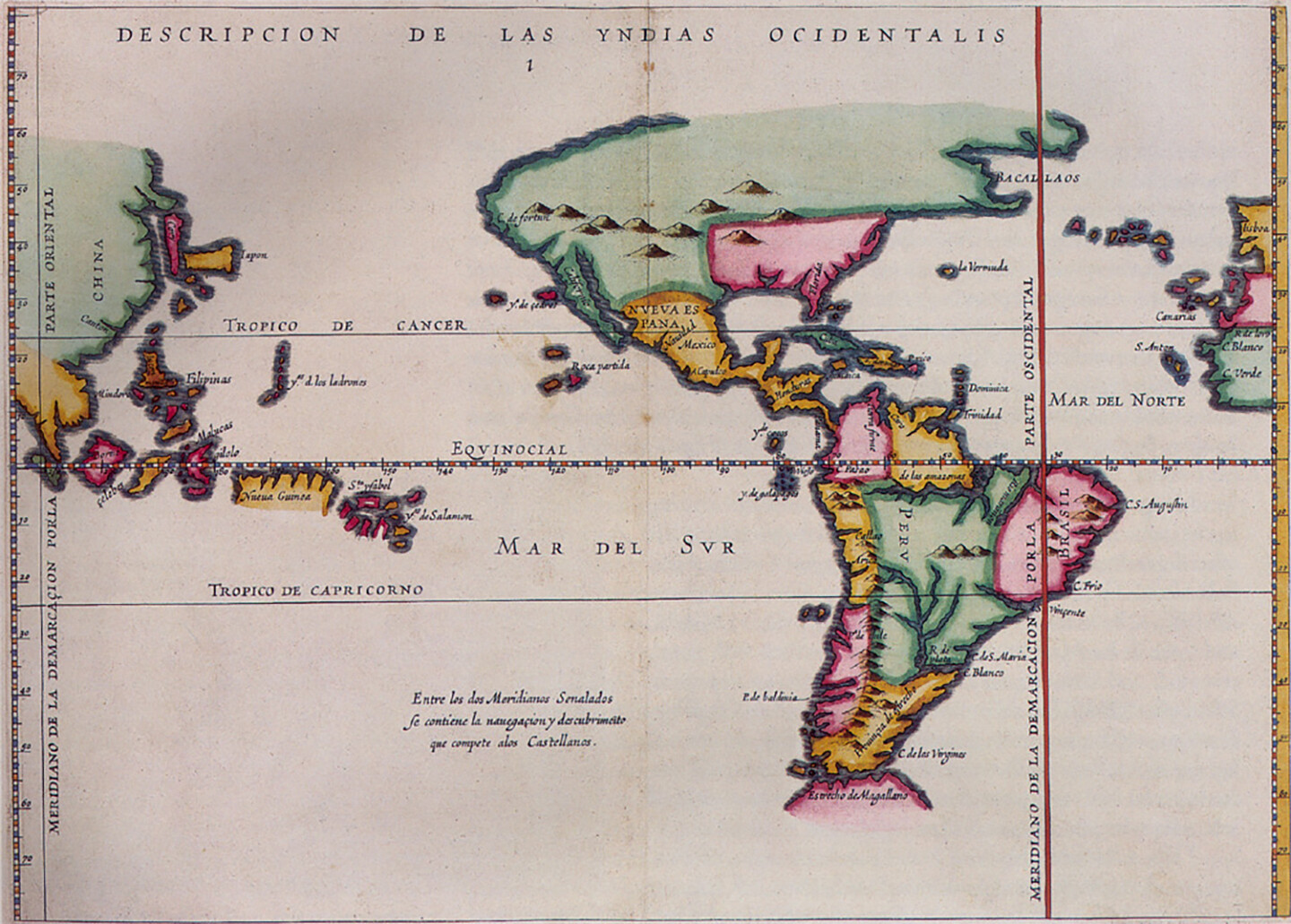

This Westphalian magic born in Europe was used to colonize the world, in places where boundaries never had such clear meanings, locations, or functions. Prior to colonization, for instance, there were multiple words in the Arabic language that could be used to describe the blurry zone between one dynasty and another. People and things moved freely, and words such as atraf that described the areas within which movement took place, mostly “meant a swathe of land, a more or less broad zone, separating two political entities where people could and did switch their allegiance back and forth between political powers.”5 Atraf was negotiated every time someone moved and by the different individuals or communities that were moving. The conception of borders as a barrier, as an instrument of spatial enclosure and distinction between people linked to nationality and defined by states, was absent from the collective imagination.6

Colonialism could not operate without restricting the mobility of the colonized while facilitating it for the colonizers. This gave birth to the current technological, bureaucratic, and administrative identification practices that determine who can and cannot cross the border. Those who make and maintain borders believe in this Westphalian magic: in linking the right to mobility to identity; in turning chance into destiny; in exercising power over the seemingly uncontrollable movement of people, viruses, and escalating environmental catastrophes. Nonetheless, while borders shapeshift and are displaced from one location to another, turning and changing our perception of people and things, borders never work as they are supposed to. No border can stop all that which moves. Against the magic of the border, there is counter-magic.

Smugglers, for instance, work by changing the perceptions of border guards: they make an Iranian be seen as a Greek; an Afghan as a Korean. Smuggling consists of different levels of materialities and a range of technics, from creating and forging specific papers, passports, and supporting documents, to using and repurposing vehicles, nodes, and infrastructures of travel. Smugglers teach us that what might be seen as magic of the border is actually a series of technics and tactics that can be countered with the same means. To see like a smuggler is to shift the attention from the spectacle of walls and fences to details, techniques, operation and performance of borders.7

In prosecution documents from a 2006 Swedish court case against Amir Heidari—a well-known migration facilitator, or in official language, human smuggler—several pages detail Photoshop files of forged passports that were found stored on a computer in his apartment. In an earlier police investigation of Heidari, officers referred to Photoshop as a forgery program. To see Photoshop as a forgery program is not wrong, for forgery, like its counter-part works by composing different elements into a single, new, flattened image. For instance, the first page of an official passport can consist of more than thirty placeholders, layers, and elements that, when composited together in the right way, magically produce a national identity. What the forger does, then, is recognize these layers and rework them to configure and secure this identity to a specific body, one that it was not associated with before. The magic produced by this association is something both states and forgers share in their practice of passport making.

Harsher border controls and the increasingly uneven access to safer means of mobility are evident in the development of smuggling technics in recent decades. Migrant smuggling to Europe in the 1980s involved actors such as airport staff, airplanes, and forged passports. Once these methods were clamped down on by authorities, other technics were adopted, such as hiding in trucks and lorries amongst cargo. As a result of subsequent security methods for checking these vehicles, maritime routes and unseaworthy boats became the most accessible technics for crossing. Smuggling techniques tactically respond to the border being crossed and what is being smuggled.8 But these shifts are not simply responses to the border system. Rather, they form the very foundation of how borders operate. This means that any border, regardless of its magical effects and technological components, will be reworked by those who touch or are touched by it.

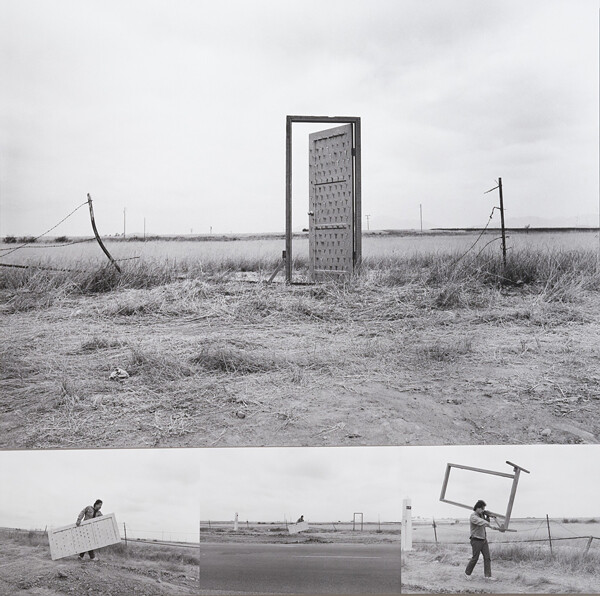

Richard Lou, “Border Door,” 1988. Source: Jim Elliott / Vincent Price Art Museum.

We should not forget, however, that more than anything else, the intense spotlights of magic and counter-magic dazzle our eyes, spellbind us, and make our gaze fixed only on borders. The obsession with the actual borders stops us from seeing histories, economies, and politics around and behind borders. To counter this, we may need other means to understand the injustices and inequalities shaped by borders. In his novel Exit West, Mohsin Hamid uses magical doors for border crossing, while in Atlantics, Mati Diop uses the metaphor of ghosts for those who cross the sea to Europe.9 We need ghosts and supernatural means to understand the current border regime between rich states and poor nations. How else can we understand the very basic logic of the border: the magical power to turn chance into destiny?

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983).

Customs and smuggling only exist because borders change the exchange value of commodities that cross them.

“Beautifying the border proposal replaces US-Mexico fence with landscaping” Dezeen, December 20, 2016, ➝.

Sarah Green, “A Sense of Border.” In Thomas M. Wilson and Hastings Donnan eds., A Companion to Border Studies (Sussex: Blackwell Publishing, 2012), 575.

Fatima Ben Slimane, “Between Empire and Nation-State: The Problem of Borders in the Maghreb.” In Dimitar Bechev and Kalypso Nicolaidis eds., Mediterranean Frontiers: Borders, Conflict and Memory in a Transnational World, (London: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 39.

For example in the Maghreb region, such unclear or uncoherent definitions existed until French colonial forces introduced Westphalian border logics, which could not tolerate the absence of control over mobile bodies and goods.

Mahmoud Keshavarz and Shahram Khosravi, eds., Seeing Like a Smuggler: Borders from Below (London: Pluto Press, forthcoming).

While smuggling by air is concerned with hiding the identity rather than the body within a legalized mobile crowd, smuggling by land, which involves using crypts and compartments, or hiding in trucks and containers, is concerned with hiding both identity and body within a legalized vehicle or cargo. Smuggling by sea, meanwhile, is concerned with hiding both identity and body via an irregular vessel.

Mohsin Hamid, Exit West (Penguin Books, 2017); Mati Diop, Atlantics (2019).

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.