¶

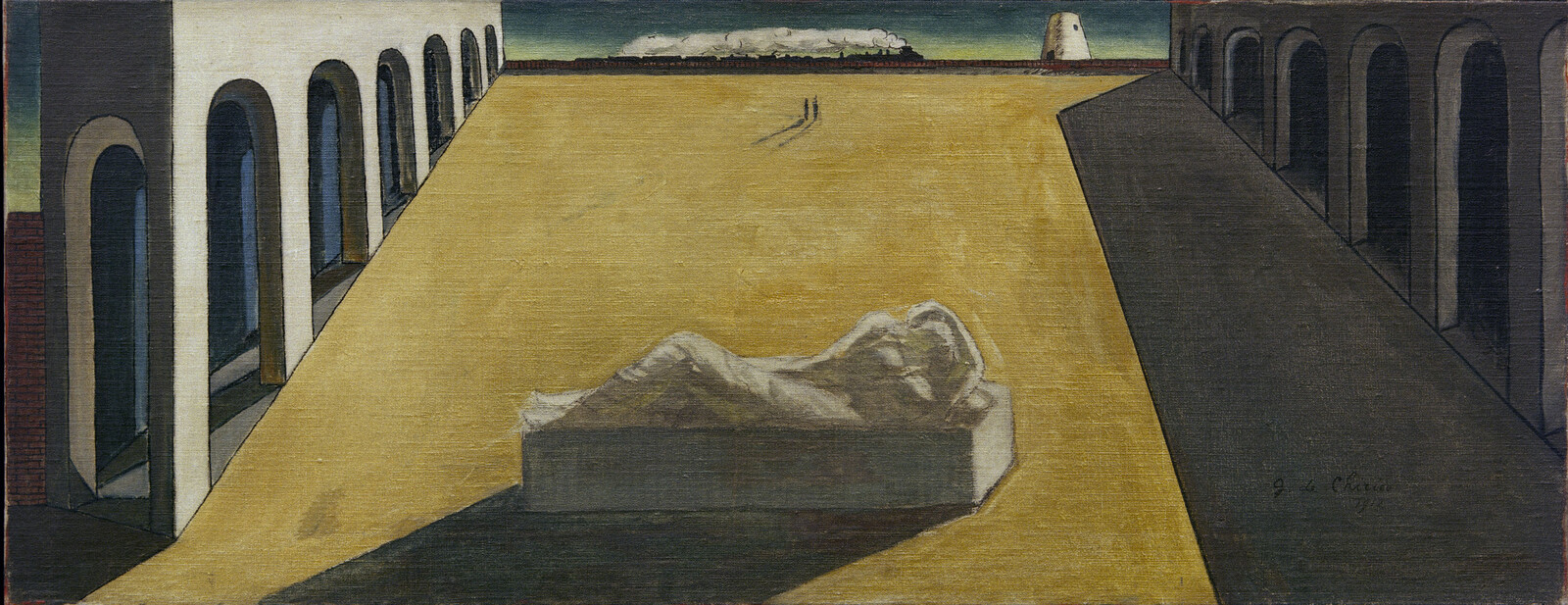

I imagine limbo as an extraterritoriality without walls, without corners, windows, entrances or exits. I can also cast it as ocean and desert wilderness. Or a blind-black void that has swallowed all light and matter and threatens a sublime death. “’Tis a strange place, this Limbo!” Samuel Taylor Coleridge imagines “Time and weary Space / Fettered from flight, with nightmare sense of fleeing / Strive for their last crepuscular half-being.” (As Ridley Scott’s Alien warned audiences: “In space no one can hear you scream.”) Limbo might bring to mind a zone of white nothingness. A space of minimalist perfection that looks like a giant infinity curve or the interior of a contemporary art museum. In his essay “Inside the White Cube,” the artist and critic Brian O’Doherty describes the effects of the “unshadowed, white, clean, artificial” spaces of the art gallery, in which art “exists in a kind of eternity of display, and though there is lots of “period” (late modern), there is no time. This eternity gives the gallery a limbo-like status: one has to have died already to be there.” Limbo is at the apex of visual sophistication: an extra-dimensional loft done out in luxury-plain Jil Sander grey. Empty and placid, with not even a reproduction Eames chair to interrupt the anodyne tastefulness. No mess, no color, no life. No hint of recidivist ornament—Adolf Loos would have loved limbo. In Harold Pinter’s words, a “No man’s land, which never moves, which never changes, which never grows older, which remains forever icy and silent.” (And full of dread: “Nomaneslond” was the fourteenth-century name for execution sites to the north of London’s city walls.) No day, no night, no seasons. “Lank space,” Coleridge called it. Or is it? By definition it stands for an in-between space. Limbo appears at the edge of daybreak and at dusk. It’s a cusp word used for conversations held in the golden hour.

Limbo; that corporeal first consonant, the symbolic, annular nothing at the end of its second, the deliciously dumb sound that both sing together. How do you define a secular nothing into which you can drop anything? This green zone’s permutations are many. For comics fans, Comic Book Limbo is where old or unwanted characters are dumped by their publisher, DC: Animal Man, Merryman, Ace the Bat-Hound, The Gay Ghost. In the final instalment of The Wachowski Sisters’ Matrix trilogy, limbo is anagrammatized into Mobil Avenue subway station, and in Christopher Nolan’s action flick Inception, it’s the name of an “unreconstructed dreamspace” into which a pair of lovers retreat. The titular free spirit in Andre Breton’s 1928 surrealist novel, Nadja, announces: “I am the soul in limbo.” When she is committed to the Vaucluse sanitorium, the narrator observes: “The essential thing is that I do not suppose there can be much difference for Nadja between the inside of a sanitarium and the outside.” The Man From Limbo is a novel written in 1930 by Hollywood screenwriter Guy Endore, later blacklisted as a Communist; limbo is the poverty from which the book’s hero tries to escape, and where Endore later found his career had slipped. The Man From Limbo is also the title of a 1950s noir detective story by John D. MacDonald in which a damaged army veteran on his uppers, coerced by his shrink to become a salesman, gets caught up in a political corruption scandal—limbo is where the anti-hero’s war trauma has consigned his dignity.

For the Danish game developers Playdead, Limbo is a quiet, puzzle-solving videogame about loss. In Hirokazu Kore-eda’s 1998 film After Life, a drab administrative center-cum-film studio processes dead souls on their way to heaven. Here, social workers help the souls identify their happiest memory. The dead wait patiently in limbo as this memory is recreated for them to experience for the rest of eternity. The subtitle to John Wallace Spencer’s Limbo of the Lost, written in 1969, promises “Actual Stories of Sea Mysteries.” Limbo District was the name of a short-lived but influential band in Athens, Georgia, during the 1990s. I am told that in Marseille there is a neighborhood bar with a sign in the window which declares: “Bienvenue dans les limbes.” For the Long Trail Brewing Company in the US state of Vermont, Limbo is the name of an India pale ale. On the bottle’s label a skeleton sits beneath a blood-red tree, bringing to mind the one about the skeleton who walks into a bar and orders a pint of lager and a mop.

¶

One technical issue with being “in limbo” is that they abolished it in 2007. Said they were doing so for the sake of the kids. As “they” were the Catholic Church, the kids could tell you this was no guarantee of anything. Limbo had been struck from the Catholic catechism in 1997, but the concept had not been officially dismantled. Following a three-year consultation authorized in 2004 by Pope Benedict XVI the church finally nailed up the shutters and boards with a 41-page report from the Vatican’s International Theological Commission, snappy title: “The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptized.”

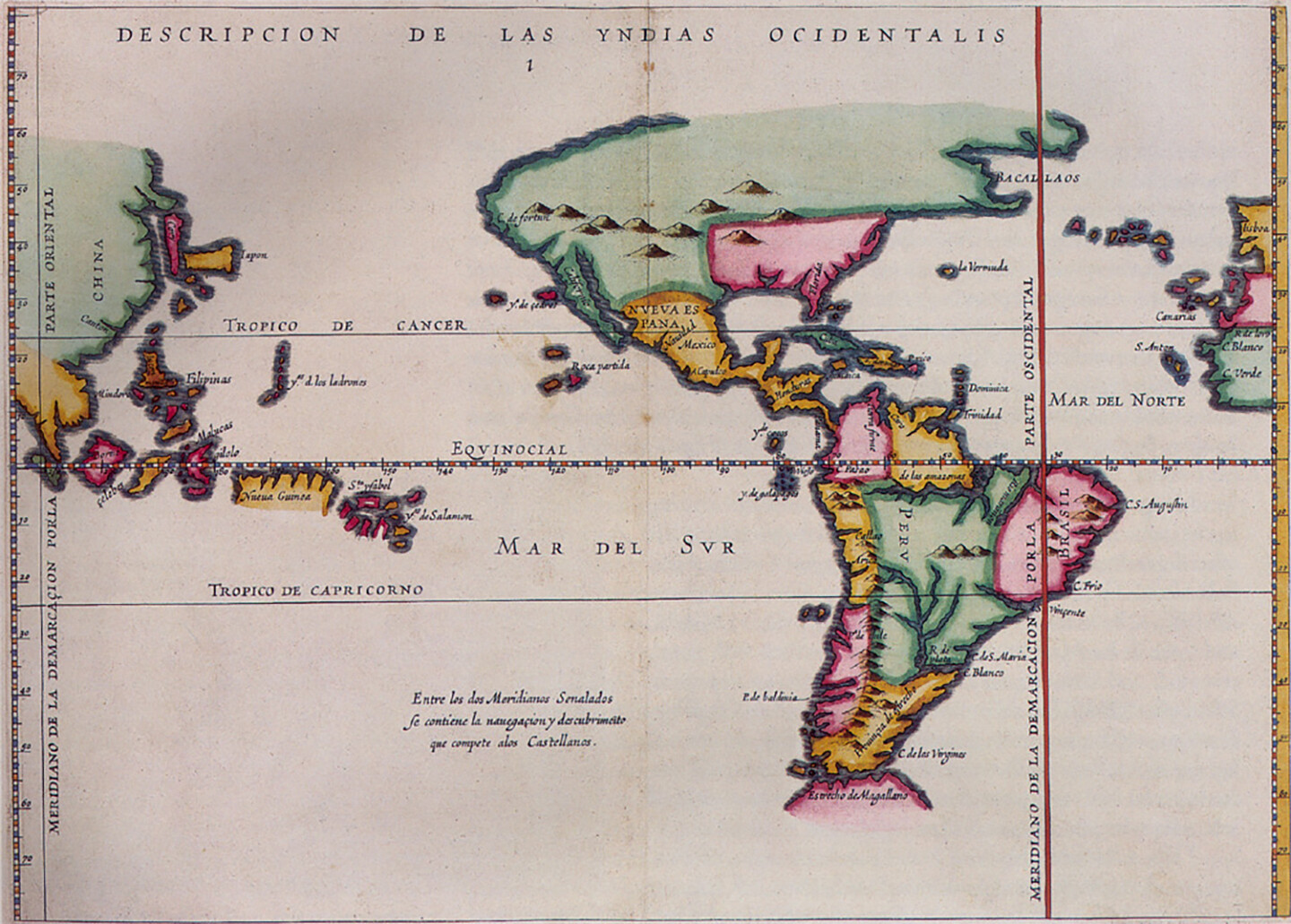

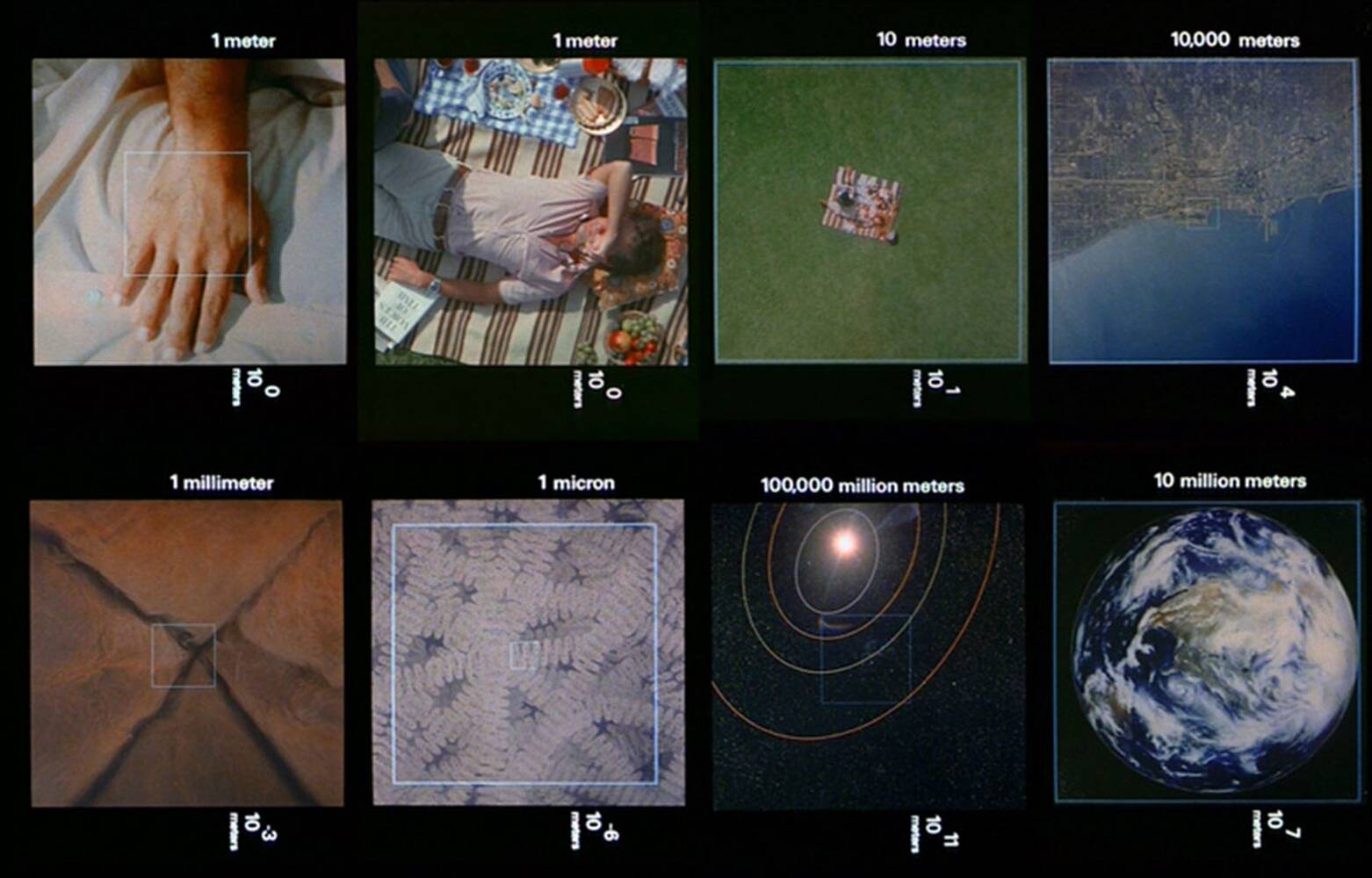

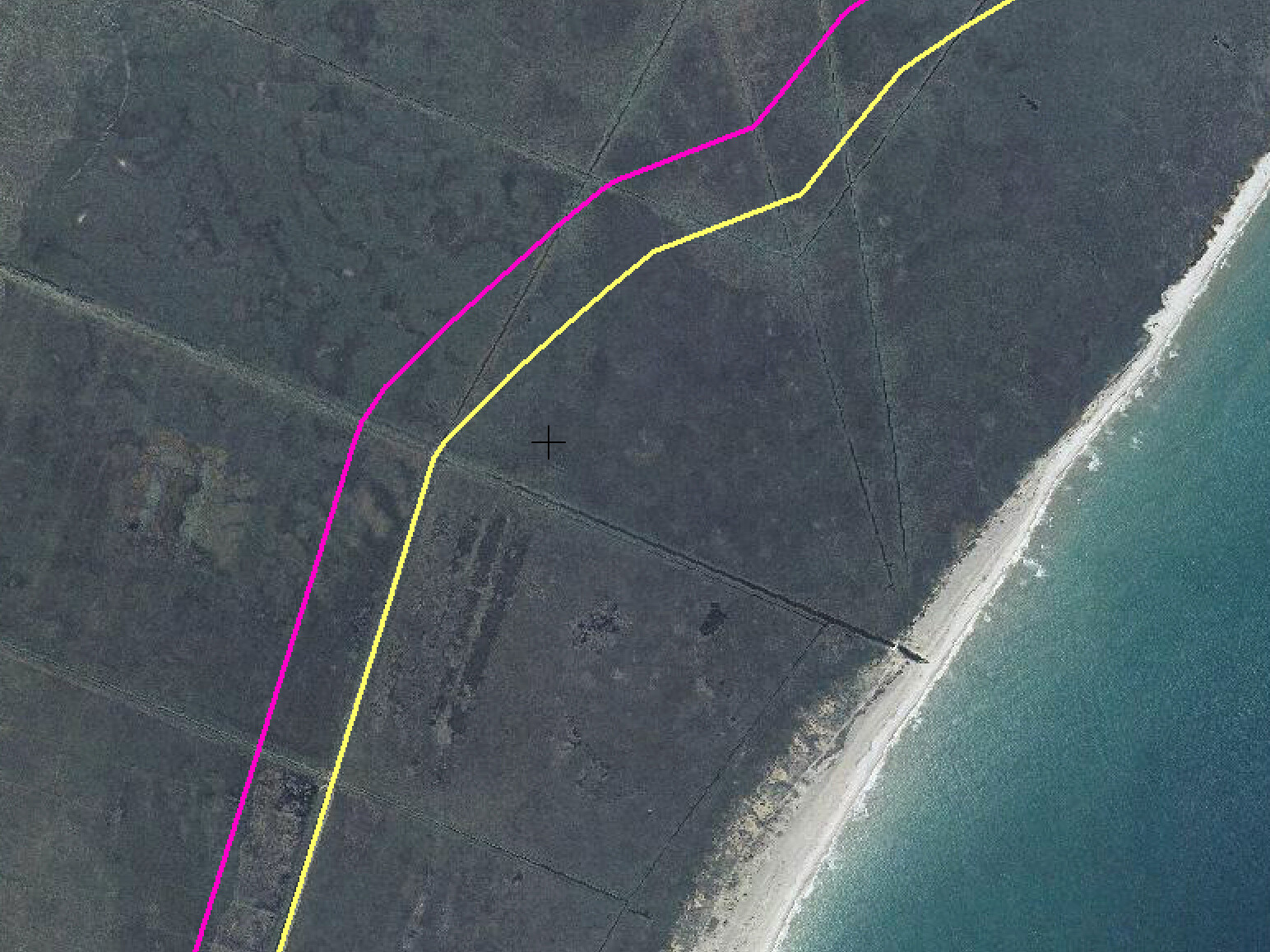

Like any religion, the Roman church likes to think of itself as eternity’s One True Department of Planning. But theirs are not the afterlife’s only theological zoning laws. Zoroastrians teach the existence of hamistagan, a holding pen for souls whose good and bad deeds are of equal weight, and Tibetan Buddhists believe in the bardo, a transitional state between death and reincarnation. In Islam, there is barzakh (from the Persian for “barrier,” or “partition’), an interstitial period spent between death and Bihar al-Anwar, the Day of Judgement. According to the scholar Meir Lubetski, the word “lmn,” in its earliest usages in the Mediterranean cultures of the Bronze Age, meant a point where land and sea met, or a harbor. In Latin the word limbus, meaning “hem” or “border,” first described the edges of the Roman Empire. The word evolved to mean spaces of transition and in-betweenness. In today’s secular usage, it refers most commonly to an interstitial period of uncertainty awaiting a decision. In that sense another way to describe mystery. Blind-spot geographies: The Bermuda Triangle, Area 51. Limbo can be the paralysis brought about by seeing life’s antagonisms from multiple perspectives. It is also a way station for the exile. Worse, a state of abandonment. The word stretches from existential captivity to real states of incarceration. Limbo is border country in which to wait in uncertainty for something, or rot in certainty for nothing.

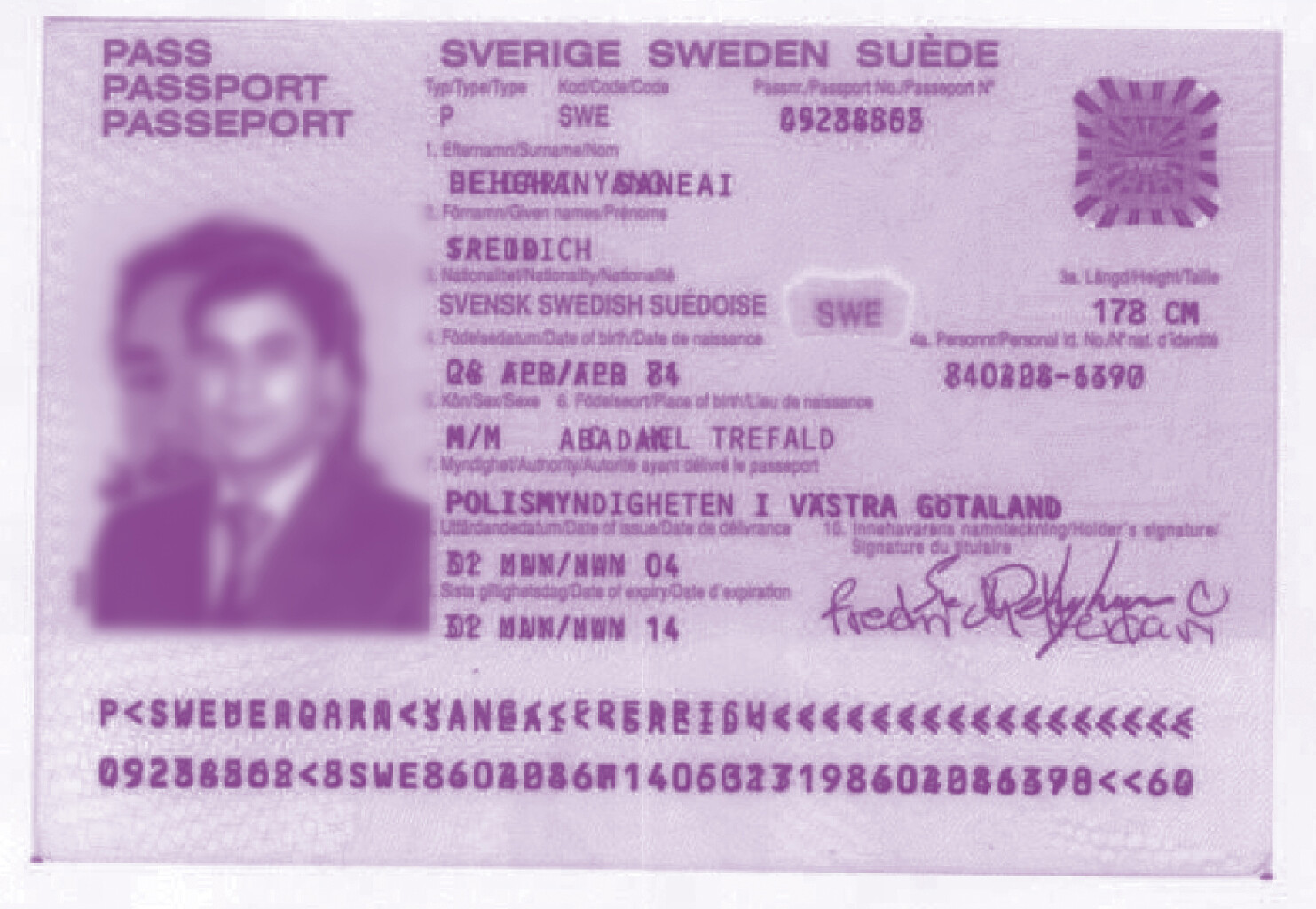

The closure of limbo’s R.C.C. branch made no discernible changes to earthly affairs. Pope Benedict’s removal of limbo from the pan-dimensional hereafter in 2007 did not result in long queues at the Post Office melting away, or an end to hours delayed in airports trying to find comfort on seats designed by people who understood “ergonomics” to be spelled “p-u-r-g-a-t-or-y.” To this day, buses still do not turn up on time when the weather is bad and you’re late for work. The automated message “We are currently experiencing a high volume of calls” continues to cast us as heroes in our own personal Franz Kafka adventure. (I wonder what hold music they played in limbo? A lone, unchanging drone. A perpetual bridge that never reaches its chorus. A lock-groove loop of Windmills of Your Mind: “Round like a circle in a spiral, like a wheel within a wheel / Never ending or beginning on an ever spinning reel…’) Decisions pending about relationships, job applications, school exams, plebiscites, credit card applications, overdraft extensions, medical tests, government inquiries, insurance claims, buying a house, coming out, having children, getting married, getting divorced, gender reassignments, court hearings, parole hearings, euthanasia cases, autopsies and death sentences all still pend. When Pope Benedict’s Catholic theologians began grappling with their faith and metaphysics, Mehran Karimi Nasseri was entering his fifteenth consecutive year living in Terminal 1, Charles de Gaulle airport, trapped without papers and no way of entering France nor returning to Iran, his country of origin. (He was finally admitted to an uncertain future in Paris in 2007, just months after limbo’s abolition. Perhaps the Vatican was onto something.) In 2013, the intelligence whistleblower Edward Snowden spent forty days waiting at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport whilst on the run from US authorities. The disappearance of limbo did not enable Constantin Reliu to escape from legal abeyance either. The 63-year-old returned home to Romania after 20 years living in Turkey to find he had been officially declared dead, despite turning up to a court hearing to dispute his own death certificate in March 2018.

Millions of asylum seekers, refugees, immigrants and stateless people remain stuck without countries to provide them with membership of a political community—the citizenship and passport that would afford them what Hannah Arendt called “the right to have rights.” Refugee boats roam the Mediterranean, refused harbor in port after port. Families are torn apart at the US frontier, and the children are put in cages then lost into social services facilities across the country. They continue to wonder if they will ever be reunited. Limbo, weaponized.

“Cultural identity is not fixed, it is a moving feast,” said Stuart Hall, who saw history and origin as an “unfinished conversation,” but try inviting the strong-arm nativist to that meal. The aggressive and aggrieved who try to push the world to the political right blame many problems on those who cross national borders in search of a different life. Populists fixate on fixing borders because they provide ways to control the bodies they fear (due to ethnicity, sex, gender, class) and the bodies they crave (those similar to their own, or most easily exploitable for political gain). No matter how far across the world you move, the one place from which you can never escape is your own flesh and blood. Knees that crack, feet that ache, a belly that needs feeding, a mouth and tongue trained to form words in a certain way, speech patterns that give away your origins, sicknesses that warn you of a toxifying world. Your brain is always housed in that same place, regardless of where your online presence may be broadcast. Limbs and organs can move from continent to continent, accompanied by whatever phone, laptop or other internet portal made from plastic and metal keeps you logged into your digital life, but those body parts can never take a holiday from each other. (Even an arm or a leg that has been lost can still persist in the cognitive wheelhouse of the amputee as a functioning part of the body—a phantom limb.) Many bodies cannot travel without abuse, hassles, refusals, restrictions nor the assumption that all bodies can walk up stairs and have the strength to push open doors and the eyesight to read signs.

Common phrases used to describe belonging, to signify some form of home, are spatial: “fitting in,” say, or “being in a good place” emotionally. Few would say they enjoy “being a round peg in a square hole.” We might correlate these ideas with musical images of being “in unison,” “in harmony,” “in accord,” “attuned”—that is, living and working with people who are of similar mind. It’s language rooted in having bodies that need physical places to comfortably inhabit, amongst neighbors who will include rather than exclude us. The liminal area of one thing, by definition, has to meet the edge of something else even if that’s thin air. Limbo suspends bodies and minds in-between. Such as Stephanie, who, as The Velvet Underground sang, was stuck “between worlds,” and wanted to know “why it is though she’s the door, she can’t be the room.”

Lines that traditionally demarcate gender and sexuality wobble, break and reconstitute themselves in new forms. In the arts, to “break boundaries” is virtuous to the point of cliché. Some rejoice at this whilst others entrench in fear. New, stronger partitions are called for by those scared of change and what they do not wish to understand. Paradoxically, similar entrenchments play out amongst those who would ostensibly wish for all borderlands to disappear. “Oppositional politics are often shaped by the very thing they oppose,” writes Paul Clinton. “Accusations flung at “cis white men” reinforce the kinds of essentialism that those who believe in gender fluidity would seek to escape.”

Power to define the center is power to define the edges. Groups who do not find acceptance in the middle are pushed out on a limb. Mistrust dogs those who dare to go “too far,” who are seen to violate inner boundaries in pursuit of spiritual or therapeutic self-knowledge (with, for instance, mind-altering drugs), or outer ones in the name of science—think of Dr. Frankenstein’s tragic Promethean experiment. Yet for some, a life at the margins is a matter of principle. Those who live dangerously, taunting death by courting misadventure through drugs or the adrenaline highs of extreme sports. The post-war figure of the artist whose integrity hinges on a refusal to sell out to the mainstream. But in hinterland new centers are built: the adoptive family or radical commune, say, who have rejected conventional structures of community in search of different models of kinship. Given time, the center will expand and eventually swallow the edgelands. What to one generation’s eyes seems too extreme—too fringe or avant-garde—will with slow, tectonic inevitability, become accepted into the canon, forming mainstream attitude, or even paragon conservatism. Carefully performed attitudinal indifference—hanging back from the center, playing it cool at the edge of the room—can congeal into inertia and cynicism. In the most extreme cases it can stop a person from doing anything for fear of losing their cool—stasis anxiety. Now the value of “cool” is monetized and recoded, used by the wealthy and privileged to police social boundaries between themselves and those they consider beneath them. And so we find ourselves back in an extra-dimensional loft done out in lifeless luxury-minimal Jil Sander grey.

¶

For medieval Catholic theologians, limbo—often conflated with purgatory, an overheated waiting room processing souls with checkered pasts—was a place for the church to dump bodies that did not carry the correct paperwork. (In a letter written to his fictional friend Malcolm, C. S. Lewis described purgatory as an astringent mouthwash to be drunk after “the tooth of life is drawn and I am ‘coming round.’”) The name applied to two zones: limbus patrum (Limbo of the Fathers), and limbus infantum (Limbo of Infants). Limbo of the Fathers existed on the fringes of Hell and was a place reserved for men who had died before Jesus Christ lived. Where the old prophets waited in unfinished happiness was a restricted ward, but not a penal confinement. In his fifteenth-century painting Christ in Limbo Fra Angelico depicted limbo as a dark and cool cave. A simple, classical arch has been carved at its mouth, as if the entrance to a secret system of passages drilled deep inside a mountain. A century later, a follower of Hieronymus Bosch dumped limbo on the bank of the River Styx, beneath an acrid smoke-filled sky—souls huddled together beneath the entrance to a light-filled tunnel where Christ is to rescue them. In the fourth canto of his Inferno, Dante Alighieri—writing in exile from his home town of Florence—describes limbo as a twilight grove where those who were without sin but who had “lived before the Christian age” waited patiently until Christ descended to the underworld for the Harrowing of Hell, liberating them to enter Heaven. “Here in the dark (where only hearing told),” writes Dante, “there were no tears, no weeping, only sighs / that caused a trembling in the eternal air— / sighs drawn from sorrowing, although no pain.” Gustave Doré, illustrating The Divine Comedy in the 1860s, stayed close to Dante’s vision, depicting limbo as woodland frozen in crisp, monochrome moonlight. Dante’s guide, Virgil, points out Old Testament saints: Abel, Noah, Abraham, David, Rachel. Walking amongst the trees they see the pagans Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucan, amongst others. On a “verdant lawn” Dante and Virgil meet the Greeks—Socrates, Plato, Euclid, Hippocrates, Zeno—the Muslim philosophers Avicenna and Averroës, and a contemporary figure, the warrior-sultan Saladin, widely admired by the Crusader armies who fought him.

Limbus infantum offered no route out. Here were the souls of children who had died before receiving absolution from Original Sin through baptism but were considered too young to be capable of committing personal sins. (Provision in limbus infantum was also given to those suffering from mental illness.) St Augustine held that limbo would make these infants aware of their privation from God. Thomas Aquinas rejected Augustine’s assessment. Innocent, but with no knowledge of God’s grace nor the possibility of salvation, Aquinas argued that these children would look forward to an eternal state of joy in limbo, not a cosmic workhouse, for they could not miss what they did not know existed. Ignorance was bliss in The Great Big Creche in the Sky. When William Blake painted “Homer and the Ancient Poets,” he gathered the Greek delegation to limbus patrum under low-hanging boughs, quietly comparing verse as they wait for Christ to bring them to Heaven’s wicket. But threading the ice-blues and silver clouds above them are women clutching unbaptized children condemned to limbus infantum. The juxtaposition is pointed; Blake did not believe in eternal torments. Booming populations and the spread of secularism were pressing reasons for the twenty-first century Roman Catholic Church to close shop on limbo. “The number of non-baptized infants has grown considerably, and therefore the reflection on the possibility of salvation for these infants has become urgent,” stated the 2007 Vatican report. Limbo represented an “unduly restrictive view of salvation,” as “people find it increasingly difficult to accept that God is just and merciful if he excludes infants, who have no personal sins, from eternal happiness, whether they are Christian or non-Christian.” It was also hard not to read the decision as a backhanded way for the church to address its vile legacy of sexual abuse. Doctrinal pieties meaningless to the victims of predatory clergy. In all this handwringing echoed John Milton’s satire of bells-and-smells Catholicism in Book III of Paradise Lost, where papal favors and punishments are consigned to a limbo he calls “The Paradise of Fools’:

Cowles, Hoods and Habits with thir wearers tost

And flutterd into Raggs, then Reliques, Beads,

Indulgences, Dispenses, Pardons, Bulls,

The sport of Winds: all these upwhirld aloft

Fly o’re the backside of the World farr off

Into a Limbo large and broad, since calld

The Paradise of Fools.

When the Vatican published its report, Father Paul McPartlan, a British member of the commission, hedged his bets. “We cannot say we know with certainty what will happen to unbaptized children but we have good grounds to hope that God in his mercy and love looks after these children and brings them to salvation.” Limbo in limbo.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.

Category

Subject

Excerpted and adapted from Dan Fox, Limbo (Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2018).

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.