1. The Beetle and the Seagrass Against the Port

If property depends on clearly defined boundaries … then coastal/marine property is complex and problematic indeed. A fundamental notion in managing the commons is that one needs clear, agreed-upon, defensible and socially and ecologically sensible boundaries… However, littoral boundaries are liminal; they are complex, contextually contingent, and changing, challenging those who want solid and easily defined property rights or management jurisdictions.

—Bonnie McCay1

In July 2010, a specimen of Pimelia canariensis, a beetle endemic to the Canary Islands, had been spotted in the area allocated for the construction of the Granadilla port in Tenerife. Citizens’ pressure to save the beetle obliged the local authority—as part of their environmental responsibility towards society—to ensure that the construction activity of the port was not distressing any endangered species in the area. The construction of the port had already been heavily criticized as a speculative real estate development scheme to the benefit of local politicians. While it is not clear whether the beetles had been released by environmental activists next to the development area as a tactic to delay construction, after the first endangered beetle was spotted in the area (and by the media), its presence managed to stop the entire construction project.

The European Union had ambiguously ruled four years before that Pimelia canariensis were endangered and should be saved. However, as the port was an exceptional opportunity for “the common good,” the EU eventually sentenced the endangered beetles to be kept “in place” by displacing them. In order to make this oxymoronic operation succeed, Brussels obliged Granadilla de Abona’s local government to set up the Environmental Observatory of Granadilla (OAG) as an “independent” institution to ensure that the port’s development operated within European “green” guidelines and collaborate with local environmentalists to carry out the task. As an immediate response, the independent environmentalist movement of the island released an open letter where they voiced a number of concerns. Firstly, no local environmentalist association had approved the foundation of the OAG. If they were, they might have objected to the fact that, far from being an independent organization to watch over environmental regulations, the OAG was directed by a former member of the government, who was supportive of the port.2

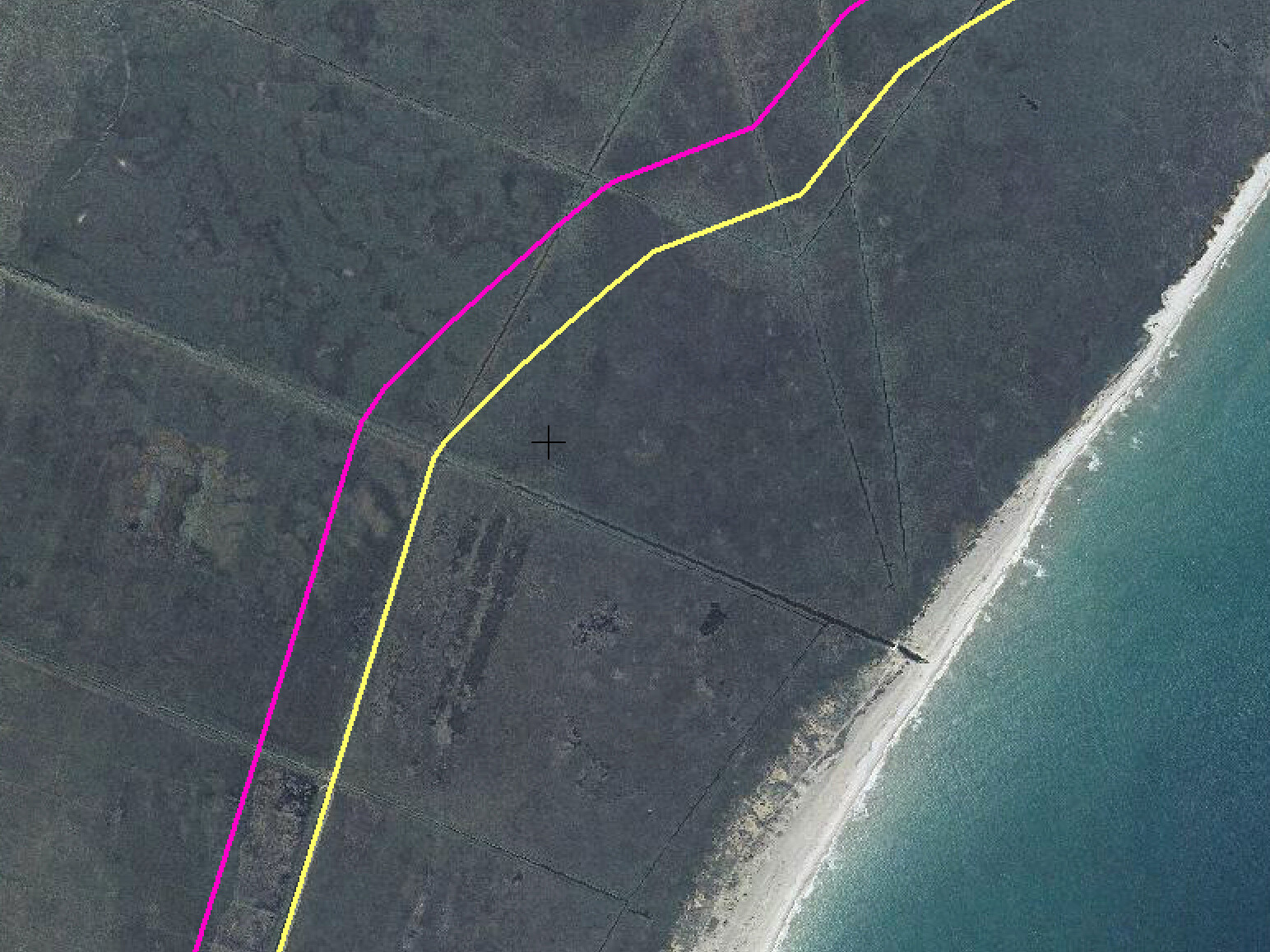

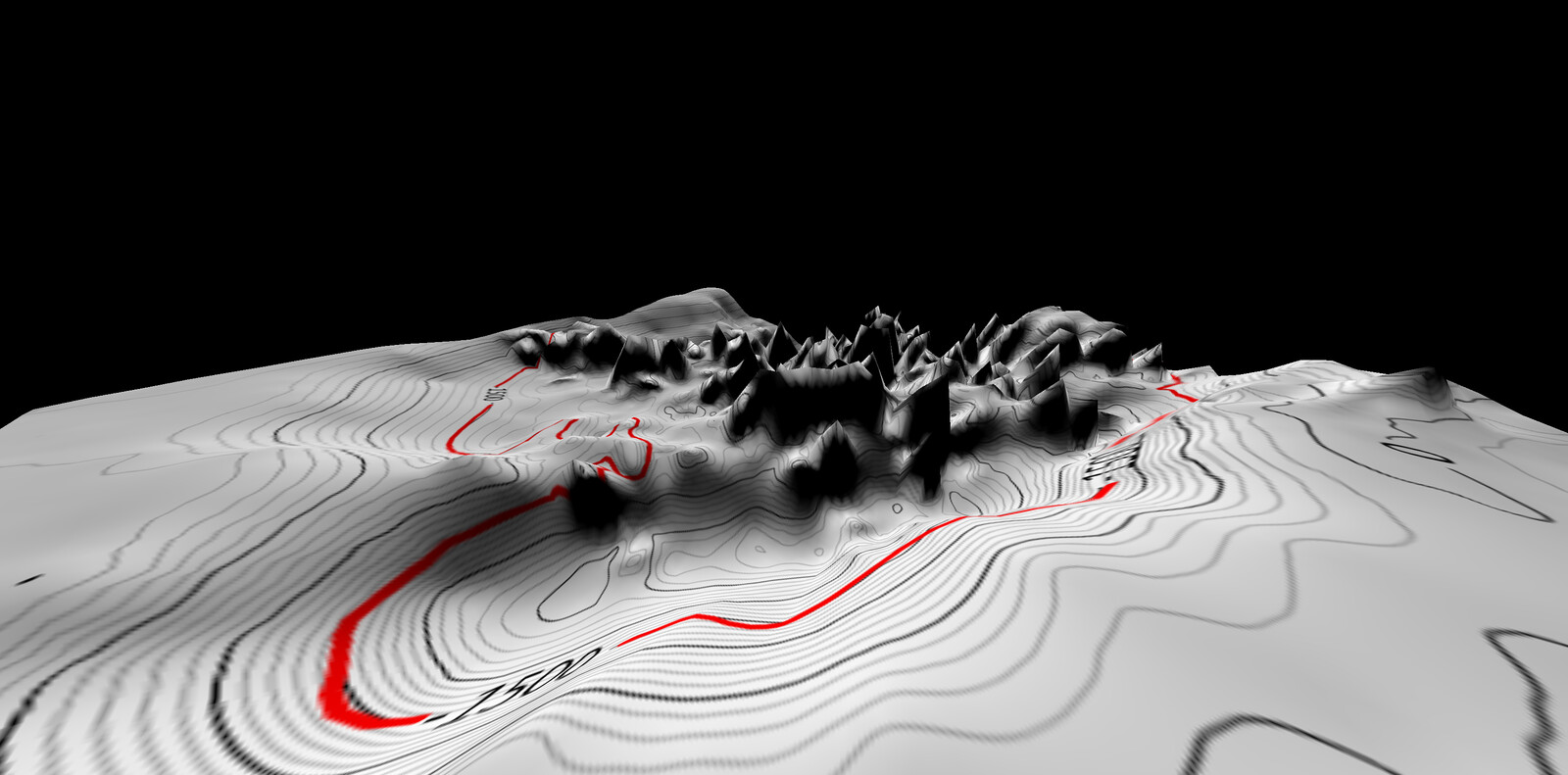

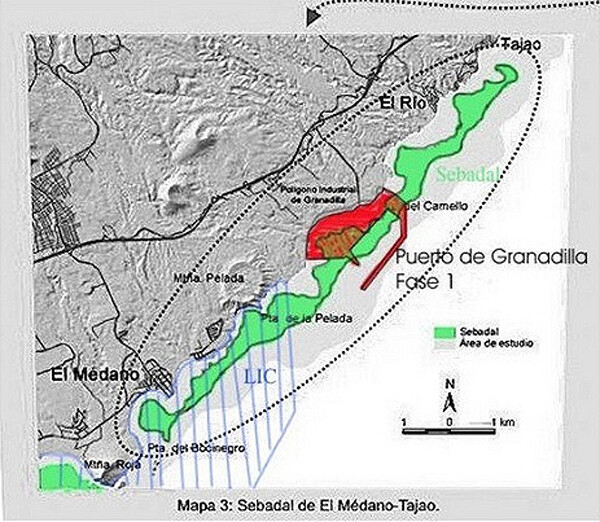

Secondly, previous to the beetle episode, the local government had excluded an endangered species of slender seagrass (Cymodocea nodosa) from the list of protected species on the island right before the announcement of the construction of the port.3 Following environmentalists complaints about the whole operation, Brussels realized the government’s failure to protect the seagrass, so the EU obliged the OAG not only to take care of the beetles, but also to properly define the extent of the endangered species of seagrass. Instead of doing this, however, the OAG adjusted the boundary of the seagrass habitat to outside the development area of the port, in contradiction to the actual extent of the seagrass. In the maps included in the environmentalists’ report to denounce the situation in Brussels, there are two conflicting geometries: the green zone—which corresponds to the actual extent of the seagrass—and the marine protected area (zoned as “Site of Community Importance” (SCI) in EU law)—whose boundary is right at the edge of the mega-port site.

The protected area for the slender seagrass (LIC, blue stripes) does not correspond to its spatial extent (green solid hatch). The port (solid red hatch) is clearly situated on top of the underwater fields of seagrass, but the protected area ends right before the site of the port. Source: El Oikos.

After EU pressure for an honest procedure that avoids dubious demarcations, the OAG produced a scientific report to explain their methodology in spotting all possible beetles, and detail how to displace them. On December 20, 2010, a group of OAG environmental technicians scouted the surroundings of the site chosen for the construction of Granadilla’s port.4 As the official report noted, they first demarcated three working sites on the coast where the beetles were believed to be most likely living. Once traps were scattered around the three sites, they were fenced off and the search began. The team combed the terrain from 10am to 12:30pm trying to find as many beetles as they could. Yet the team found that no more beetles than had been trapped during those two-and-a-half hours, and concluded that there were only eighteen specimens, one dead. It had been raining for days, so the report argued that they did not find any larvae, and thus discarded the possibility of their existence in the area.

OAG technicians later carefully released the collected specimens in a demarcated zone further inland, which was distant enough to not interfere with the new port. In the same way that they had determined the lines within which the insects could possibly be living—and not beyond—they also defined the lines within which the beetles would live from then on. Among its many contradictions, the report meticulously explained how to displace an endangered species to a “safe zone” in order to secure its habitat and the environmental and economic sustainability of the surrounding landscape (for humans). The methodology used by the OAG is problematic not only in terms of fieldwork duration, but also in the way it uses zoning and displacement as a tool to preserve space “as it is.” It not only exposes the irrelevance of their environmental care operations and the protection of coastal landscapes in the face of public scrutiny, but also the speculative profit-driven approach to territorial planning. This model, replicated across Spain from the 1960s and exponentially since the 1990s, significantly contributed to its 2008 housing crisis.

Demarcated areas of intervention with the exact location of beetle traps, scattered around three different sites. Source: OAG report, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, December 27, 2010.

In the port versus the beetle (or the seagrass), greenwashing real estate operations used environmental protection as a form of environmental destruction. The contested construction of a port in Granadilla is a paradigmatic case to dive into the struggle around the pandemic production of profit margins through building infrastructure. A coastal mega-project, Granadilla’s port has undergone constant tensions between business interests and environmentalist concerns that expose how local politicians have the agency to manufacture and govern the spatial extent of their dominions. Determining how land and sea are used is a political process that epitomizes how the architecture of boundaries is complicit with neoliberal powers in the governance of space. Ecology serves urbanization. Analogously, architecture in neoliberal governance has become a set of relations for valuing space: adapting boundaries to a conglomerate of political, economic, and environmental interests. In this sense, space is built just as much as the environment is.

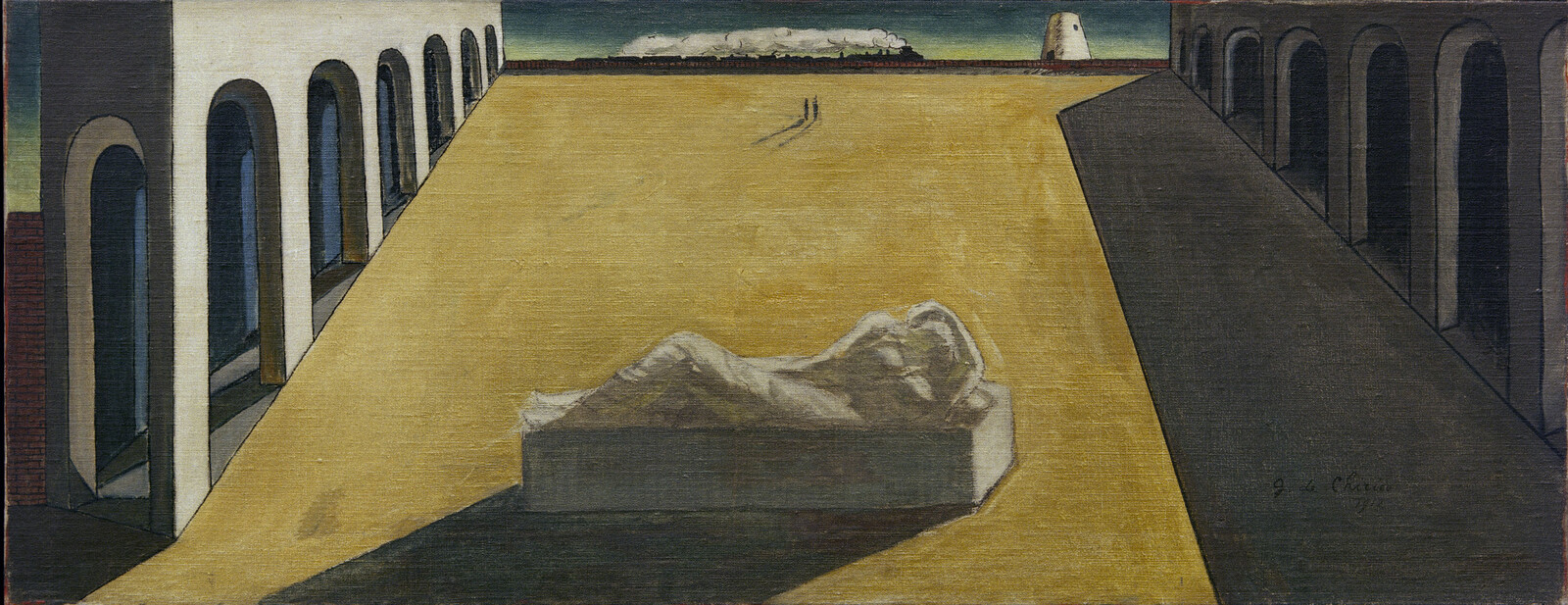

Like the conflict surrounding the seventeen endangered beetles, the 2007–2008 financial and housing crisis emerged at the frontier of ownership, between the end of the sea—the coastal commons—and the beginning of buildable, developable land. The demarcation of the shoreline is able to unveil processes of democratic erosion by real estate and other speculative forces that are based on two-dimensional understandings of “margins”—edge lines that enclose space and limit its value. Development patterns that led to the housing bubble ignored the fact that the shore is not a fixed and measurable object, but a dynamic set of relations. The sea never stops moving, and even amid the discord of the global political economy, it is a space of contradictions and alternatives, of images and laws, of labor and dreams.5 It is a grey zone, where profit and margins are constantly negotiated.

2. The Failure of the Section: Salinity Reports as Factories of Truth

Est autem litus maris, quatenus hibernus fluctus maximus excurrit.

(The shore of the sea extends to the point attained by the highest tide in winter.)

—Justinian I6

In theory, the Spanish seashore legally extends to the point reached by the highest tide in history.7 Since the Spanish Coastal Law was passed in 1988, aerial photographs and satellite imagery have been used to demarcate this line. However, the pressure of real estate development is such that consultants can be challenged to bias technical evidence. Photographs from above, whatever their resolution, can only capture a precise moment. They cannot prove whether somewhere had ever been part of the sea (perhaps at the highest tide in history). Therefore, litigation around the precise demarcation of the shore and the historical presence of the sea has led scientific researchers to work at the scale of salinity to arbitrate urban planning conflicts. Grains of sea salt have been brought to court to prove or dismantle the millenary geology of the beach and its material history.

The case of Las Teresitas Beach in Tenerife is a paradigmatic planning conflict, whereby soil samples from its margins were included in a 2008 report. They aimed to discern whether the sample site belonged to buildable land or the coastal commons. If the beach had sea salt, it would be a “natural” beach, meaning part of the coastal commons, and therefore not buildable. But if there was any way to prove that the beach did not have sea salt, or that the sea salt was not originally from the beach (“unnatural”), the area would not belong to the sea, and instead, it could be argued as buildable. As part of the legal process to demarcate the Maritime-Terrestrial Public Domain in Las Teresitas, the DL-210-TF report was produced by the public company Tragsatec. Their fifty-two-page report used photography, topography, salinity analyses, and marine archaeology to construct environmental ambiguity.

A. Aerial Photography

A series of images from 1973, 1981, 1989, and 2002 are visually compared to analyze the forces modifying the beach over time. The four photographs conclude that nearby urbanization indicates a clear anthropogenic influence, making the beach no longer “natural.”

B. Topography

Slope variations in the coastal contours were studied by cutting the cliff of the beach into four cross-sections to prove their angle, which determines whether it can be buildable land or not. The threshold of 60°—above which the slope belongs to the sea—nonetheless has to be calculated as an average for a whole beach. The analysis concluded that the average slope was between 36.02° and 44.82°. Regardless of the fact that there could have been places at more than 60°, the report argued that the site was clearly not a coastal “cliff” by definition, but a medium-slope on average.

C. Salinity

Through the study of beach sediments, the report reminds its reader that the beach is manmade. Las Teresitas Beach is the first engineered beach in Europe, dating back to the Francoist late-1960s. Its golden sands were shipped from the Moroccan Sahara Desert, as the original black volcanic sands were unappealing to northern European snowbirds seeking the “tropical” southern latitudes during cold winters.8 Samples taken for the report consisted of three deep test pits and two samples from the surface. The standard method of determining the salinity of sand consists of circulating electricity through it. The more saline, the more conductive it is. As stated in the report, despite the fact that there are various “arbitrary” salinity thresholds, Tragsatec chose to use the US salinity laboratory as a reference in this case, which determines four deciSiemens/meter (dS/m) as a threshold for salinity.9 Given that the samples from Tenerife were under one dS/m, it concluded that the site was not saline, but “normal,” i.e. buildable soil.

D. Marine Archaeology

While the Saharan sand tested from Las Teresitas did not have any particles of sea salt, the analysis revealed that there were nonetheless sea fossils present in the soil samples. However, the report claimed that the presence of sea fossils was not understood to be because of any seawater impact, but because of the wind; at some point in history, the shells had been blown to rather than washed up on the shore. It also clarified that other possibilities for their presence include sea level rise 11,000 years ago during the interglacial period, when hotter temperatures increased the sea level two or three meters over the current level, but discarded this option as “not very probable.” It even argued that because of the artificial breakwater that protects the beach from winter waves, the beach is “dead” in ecological terms: no influence by tides, waves, or saltwater could be considered. As they have not come to the surface due to tidal movements, the report concluded that the presence of fossil sediments is “unnatural.”10

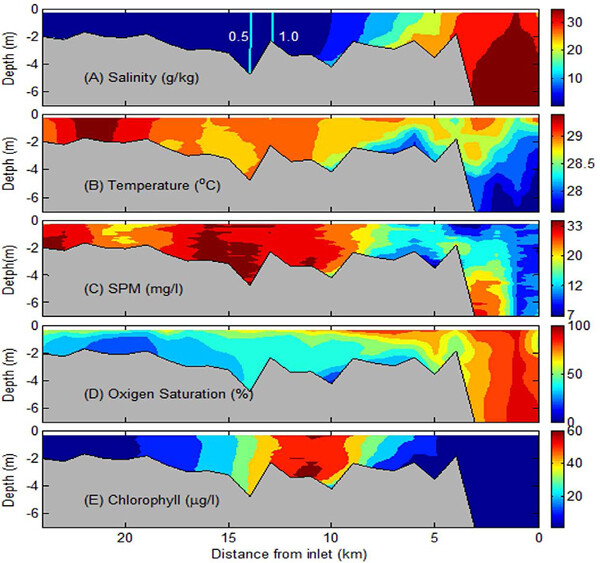

Field distributions of (a) salinity (g/kg), (b) temperature (ºC), (c) suspended particulate matter (SPM, mg/l), (d) dissolved oxygen saturation (%), and (e) chlorophyll (µg/l) along the Capibaribe Estuary in Brazil on October 11th, 2013. Source: Brazilian Journal of Oceanography, 2016.

Tragsatec’s scientific report concluded that the sector it sampled did not belong to the sea and could be urbanized based on the scientific narrative to reduce the width of the shoreline. It constructed their version of the shoreline based on factishes; with the same evidence, they could have just as easily argued the exact opposite. Ambiguity in the interpretation of what a line means is inherent to the way in which that line is visually represented.

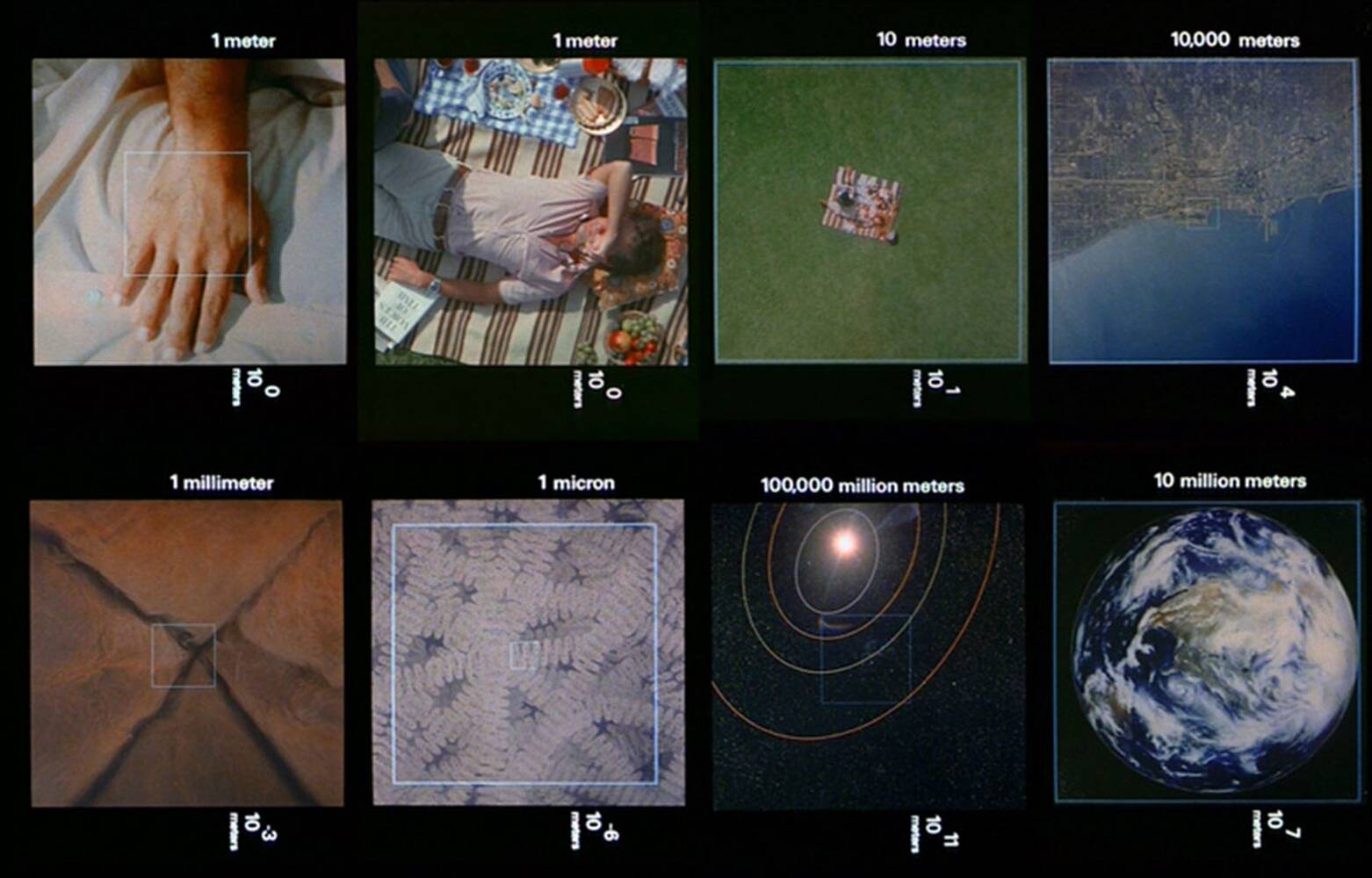

Government-drawn sections of the littoral are rather an average abstraction of what a shoreline is supposed to administratively look like in order to be easily measured. Drawing the littoral as a one-dimensional line ignores dynamic processes and multi-scalar gradients.11 Neither thermodynamic nor salinity variation are considered in current practices of graphic representation.12 Current visualizations of the shoreline are therefore obsolete. The diagrammatic sections of the littoral released by the Spanish Ministry of the Environment are not even true to the Coastal Law in their depiction of the highest tide in history and the way salt levels fluctuate. They cut through stereotypical coastal landscapes that represent any condition and none at the same time. “Typical” or “average” sections never slice through underground streams, swamps, gradients of salinity, irrigated fields with leaking drainage pipes, or nomadic dunes. Otherwise they would need to consider more complicated forms of four-dimensional representation for these ambiguous landscapes, which despite being included as part of the coast according to law, would not be possible to visualize in the same way. Contrary to the graphic legend of their schemes, water is not blue and land is not green; the littoral is murky, muddy, and rather brown.

3. Resolution of the Ruler

Calculated ambiguity [is] the ability to give diametrically opposed but legally valid answers to the same question from different quarters. Thus offshore allows individuals and firms to enjoy simultaneous ownership and non-ownership, to be high profit and loss-making, heavily indebted but also debt-free, and for investment to be foreign and domestic.

—Jason Sharman13

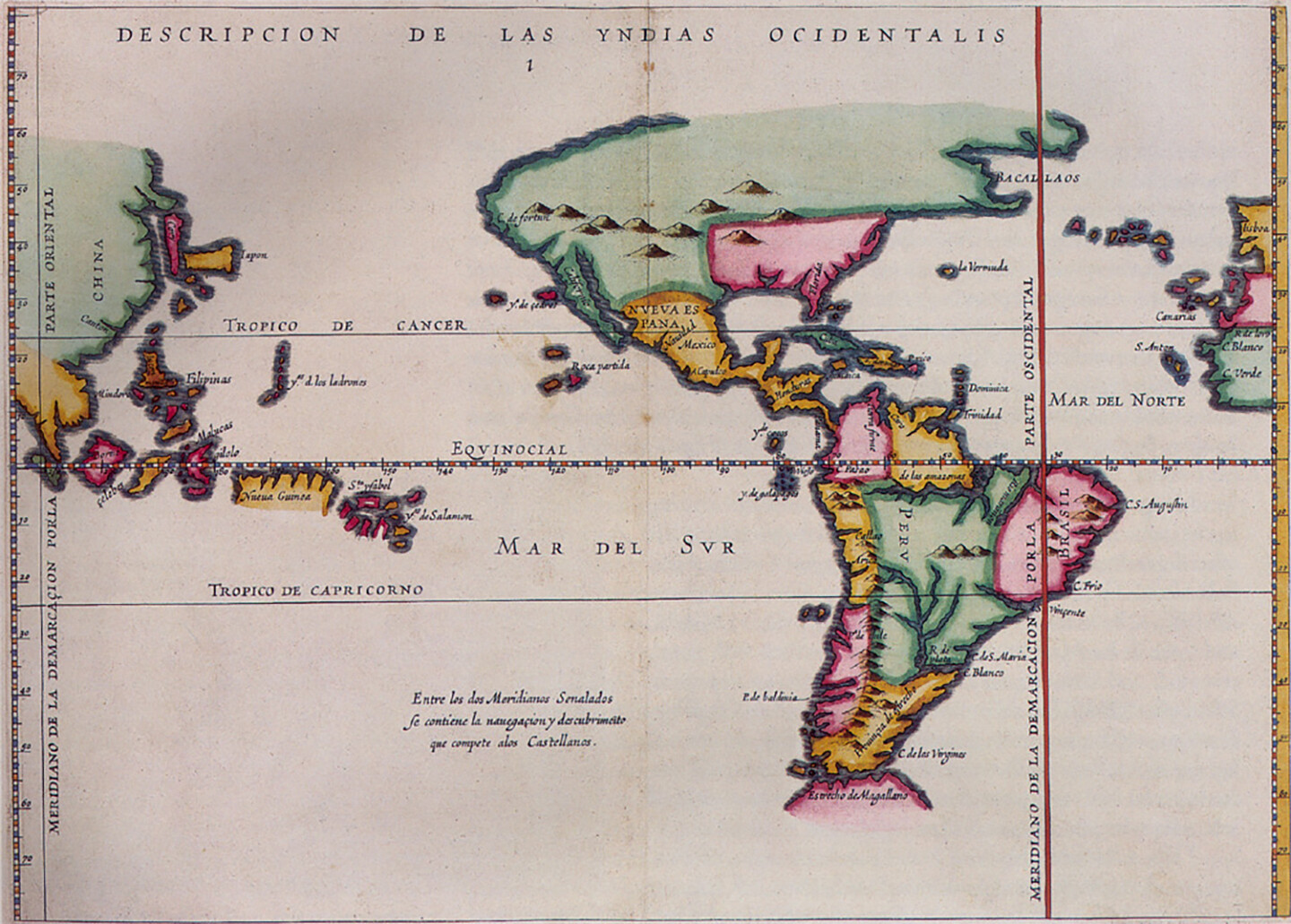

When the Coastal Law was passed in Spain on July 28, 1988, for the first time in the country’s history, a law explicitly identified the shoreline as a juridical entity in order to protect it.14 (The previous law in 1969 was merely administrative, and in any case was hardly enforced). The 1988 law opens by defining the coast according to its length: 7,880 kilometers. With this measurement, the boundary between land and sea becomes subject to political, ecological, architectural, and economic pressures.

Colliding with this legal definition, there are a series of contradictory measurements that describe the length of the Spanish coast differently: 8,000 kilometers, according to the History of Coastal Engineering in Spain by Miguel Ángel Losada et al.; 7,879 kilometers, according to the Spanish National Geographic Institute (IGN); 7,268 kilometers, according to the World Resources Institute; and 4,964 kilometers, according to the CIA-authored World Factbook.15 Mismatching dimensions referring to the same territorial boundary expose different methods of quantifying the space of the littoral and the complexity of forces negotiating between land and sea. They all straighten up the rugged coastline through disparate approximations and orders of magnitude. With every coastal twist generating concave and convex land formations, state geographers have to estimate the shortest distance between landmark headlands.

With contemporary technology, however, the governmental ruler approximating the littoral in meters or kilometers of length has been superseded by pixel resolution. Satellite imagery can potentially increase the accuracy of the line, yet in most cases, it is the microscopic materiality of sand that brings the demarcation into question: not the view from above, but from below, from the nature of the ground itself. The shoreline is not the “easily-measured” high water mark during spring tides, but rather the particles of sea salt that have to prove their presence or absence.

With his “coastline paradox,” mathematician and early weather forecaster Lewis Fry Richardson claimed that the length of a shoreline relies on the ruler with which it is measured.16 In the Spanish context, the figure of the ruler is both a subject and object: it is the authority who defines a measurement, the tool used, and the accuracy of the measurement (when a coastline is measured in kilometers, increments less than one kilometer in length are ignored). Consequently, the resolution of the ruler is what eventually designs the measured object.

By 2005, the Spanish shoreline was mapped by the IGN only along 70% of its (7,880-kilometer) length. In 2012, the shoreline was still recorded at only 95.85% of its extent, and as of 2020, the line was still not fully traced.17 Despite acknowledging its total as a round figure, the government simultaneously states the precise distances that have not yet been measured. Thirty-two years after the Coastal Law was passed, and even after further amendments in 2013 and 2014, there exists no official map with the complete shoreline of the entire country. Around 1–3% of the unmeasured length is still shown as under litigation, pending to be approved. How did the state find itself in such a situation?

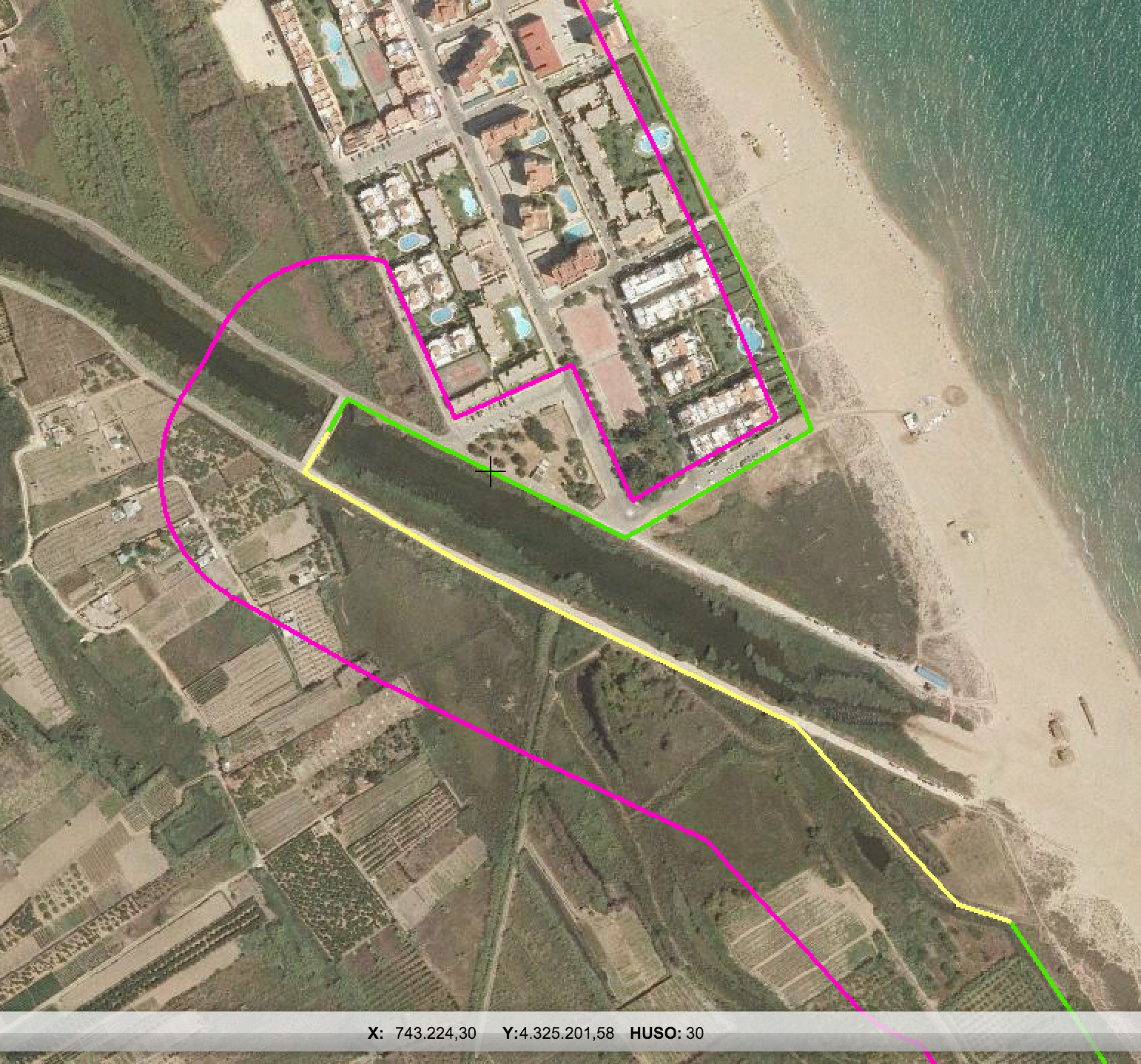

Río Vaca, Valencia. Like in wetlands, the mouth of a torrential seasonal stream (rambla) is demarcated according to the salinity degree of its waters and floodplains. However, the effects of brackish tidal waters appear and disappear almost every season depending on the strength of the storm. In this case still under litigation, the midline of the river is the boundary between two municipalities (Xeraco to the north and Gandía to the south), so the inclusion or exclusion of its banks in either the realm of the land or the sea has an impact on the territorial demarcation of the two municipalities. On the one hand, the north side claims that the Southern flood plain should be considered as part of the river, so that it could annex 600m of prime location beach from the southern side. On the other hand, the south side claims that the river should end in a straight line without considering the banks as part of the public domain, so that their beach does not shrink. The yellow line for the moment cuts across a compromised version. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Nules and Borriana, Castellón. Because of the different local authorities involved in the shoreline’s demarcation, the exact same landscape can be framed under different offset widths in adjoining municipalities. However similar the landscape is on both sides, one may be more conservative than the other in terms of their environmental protection buffer zone. Together, they create a discontinuity in the understanding of the coastal environment. In this particular case, the municipality on the north side of the line mismatch reduced the public beach and the easement of protection to the minimum (characteristic of “urban artificial areas”); whereas on the south side, the buffer zone is extended to the maximum (characteristic of “rural natural areas”). Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Puçol, Valencia. When an area is considered to be anthropized or substantially transformed by humans, the corresponding authorities can determine that is already “urban enough” to belong to “nature.” Hence, the bare minimum offset from the coastal baseline can apply, and instead of having a buffer of 100m wide, only 20m is enough. Declaring scarcely inhabited areas as consolidated urbanization is a recurrent instrument to allow buildings to stay in place or to expropriate as little as possible. In this case, the old small historic buildings are “invading” the coast, but the large resorts right behind them (that are disturbing the streams and orchard landscape) are saved from demolition. When the new resorts follow the geometry of the orchard grid plots (narrow front and deep sides), the resulting building typically have balconies oriented in an angle to have sea views sideways. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Marina Alcossebre, Castellón. These three blocks are surrounded by water, but have been legally exempted as buildable land. Despite being exclusive enclaves, they are allowed to be part of the coastal buffer. Marinas are particularly contested building typologies, as they exist in land that previously did not exist. Demolishing them to restore the “site” would imply to also restore the dredged sea bed, which is an even more expensive operation. In the case of inland upscale marinas, like Catalan Ampuriabrava, it is not less complicated, as restoration would imply not only to demolish the structures to bring the coastal wetland back, but also to dismantle the banked canals.

Moncofa, Castellón. Adaptation of the shoreline to the shape of the new development of an urbanización. It is important to note how the seasonal stream that runs through the middle of the unfinished development and the surrounding coastal dunes are demarcated with arbitrary offset lines to the end of the sea. The contested yellow line, which should theoretically indicate the end of the beach, does not even match the satellite image that shows part of the beach beyond the end of it (top). The municipality of Moncofa, with a population of 7,000, planned 31,500 new apartments to house an unprecedented migration of 120,000 dwellers that never arrived. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Río Vaca, Valencia. Like in wetlands, the mouth of a torrential seasonal stream (rambla) is demarcated according to the salinity degree of its waters and floodplains. However, the effects of brackish tidal waters appear and disappear almost every season depending on the strength of the storm. In this case still under litigation, the midline of the river is the boundary between two municipalities (Xeraco to the north and Gandía to the south), so the inclusion or exclusion of its banks in either the realm of the land or the sea has an impact on the territorial demarcation of the two municipalities. On the one hand, the north side claims that the Southern flood plain should be considered as part of the river, so that it could annex 600m of prime location beach from the southern side. On the other hand, the south side claims that the river should end in a straight line without considering the banks as part of the public domain, so that their beach does not shrink. The yellow line for the moment cuts across a compromised version. Source: Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

To understand the controversy along the length of the littoral, it is crucial to pinpoint a parallel controversy around the actual depth of the shoreline. In principle, lines do not have width, and yet, coastal land use depends on the buffer zone along the shore. The actual thickness of the littoral depends on setbacks and offset buffers between the inner end of the water and the outermost beginning of buildable land. At a European scale, for example, the shoreline is a variable strip, about ten kilometers deep.18 But in Spain, in order to calculate the population of coastal zones, the 1988 Coastal Law defined the thickness of the shore as only five kilometers wide. Even with this reduced dimension, 35% of the country’s population at the time was concentrated in an area that constituted only 7% of the national territory.19 Hence, the shoreline is a line that does not exist; it is a thick, liminal zone, and this thickness is defined differently in different contexts.

The shoreline is a considerably wide, politically-constructed zone ranging up to 500 meters from the water according to local urban planning codes and up to five kilometers according to taxonomies of human geography. The shoreline-zone allows for multiple loopholes in the definition of physical features, such as dunes, lagoons, meadows, or wetlands. Since 1988, hundreds of legal cases have challenged the definition of the shores by taking advantage of these ambiguities. For instance, if a “natural” dune is stabilized and fixed (proving that it no longer moves), it can be automatically excluded from the realm of the coast and turned into holiday homes on the seafront.20

In practical terms, littorals can be regarded as financial objects that allow for volatile markets to speculate with land value, land use, and buildable potential. The geographic calculations behind these land margins are carefully constructed through business plans, as political agents adapt the boundary between building land and the coastal commons to their own interests. The power to quantify and reclassify buildable space is at the core of an architectural struggle: evictions and eminent domain have trapped the littoral commons in court. Every twist of the shoreline reveals not where tides are active, but rather where landscape margins are entangled with real estate profit margins.

Bonnie McCay, “The Littoral and the Liminal: or Why it is Hard and Critical to Answer the Question ‘Who Owns the Coast?’,” Marine Anthropological Studies 17 (2009): 8–9.

Ben Magec, Evaluación de la Utilidad y Cumplimientos del Observatorio Ambiental de Granadilla (Tenerife: Ecologistas en Acción Canarias, 2013).

Europa Press. “Greenpeace Echa en Falta a la Posidonia del Listado de Protección,” September 13, 2010, ➝.

Pilar Bello Bello, “Traslocación de Ejemplares de Pimelia canariensis desde la Zona de Obras del Puerto de Granadilla a la RNE de Montaña Roja,” Santa Cruz de Tenerife, December 27, 2010.

Philip E. Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 210.

Justinian in George M. Cole and Donald A. Wilson, Land Tenure, Boundary Surveys, and Cadastral Systems (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2017); Lal Mohan Doss, The Law of Riparian Rights, Alluvion and Fishery (Bombay, London, and Madras: W. Thacker & Co, 1891), 34.

“Ley Orgánica 22/1988, de 28 de julio, de Costas,” Boletín Oficial del Estado, July 29, 1988.

The golden beach is now so ingrained in even the local imagination that residents have fought for the beach to keep its “natural” condition and not be built up. José Manuel de Cózar Escalante and Juan Sánchez García, “Planeamiento urbanístico y procesos sociales deliberativos: La playa de Las Teresitas en Santa Cruz de Tenerife,” in Toma de Decisiones Colectivas y Política del Suelo, ed. Juan Sánchez García (Teguise: Fundación César Manrique, 2004), 33–45.

TRAGSATEC, Estudio Técnico para la Justificación del DPM-T en la Playa de las Teresitas DL-210-TF (Santa Cruz de Tenerife, 2009), 48.

Ibid, conclusion.

Carlos Augusto França Schettini et al., “Observation of an Estuarine Turbidity in the Highly Impacted Capibaribe Estuary, Brazil,” Brazilian Journal of Oceanography 64 (2016); “Salinity,” Australian Online Coastal Information, ➝.

Climate changes will increase and accelerate transformations of these variables.

Jason C. Sharman, “Offshore and the New International Political Economy,” Review of International Political Economy 17 (2010): 1.

“Ley Orgánica 22/1988.”

Miguel Ángel Losada et al., “History of Coastal Engineering in Spain,” in History and Heritage of Coastal Engineering, ed. Nicholas C. Kraus (New York: ASCE, 1996), 465–466; “Longitud de la Línea de Costa Española por Provincias,” Instituto Geográfico Nacional, ➝; “National Coastal Length,” GEO-3 Data Compendium, ➝; “The World Factbook,” Central Intelligence Agency, ➝.

Lewis Fry Richardson, “The Problem of Contiguity: An Appendix of Statistics of Deadly Quarrels,” General Systems Yearbook 6 (1961), 139–187.

“Costas y Medio Marino,” Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, ➝.

European Union, “Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2002 Concerning the Implementation of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Europe,” Official Journal L148, June 6, 2002: 24–27.

“Ley Orgánica 22/1988.”

Sentence A.N. 04-06-03. Recurso nº 0627/1999 (DL-42-Baleares).

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.