1. Wall

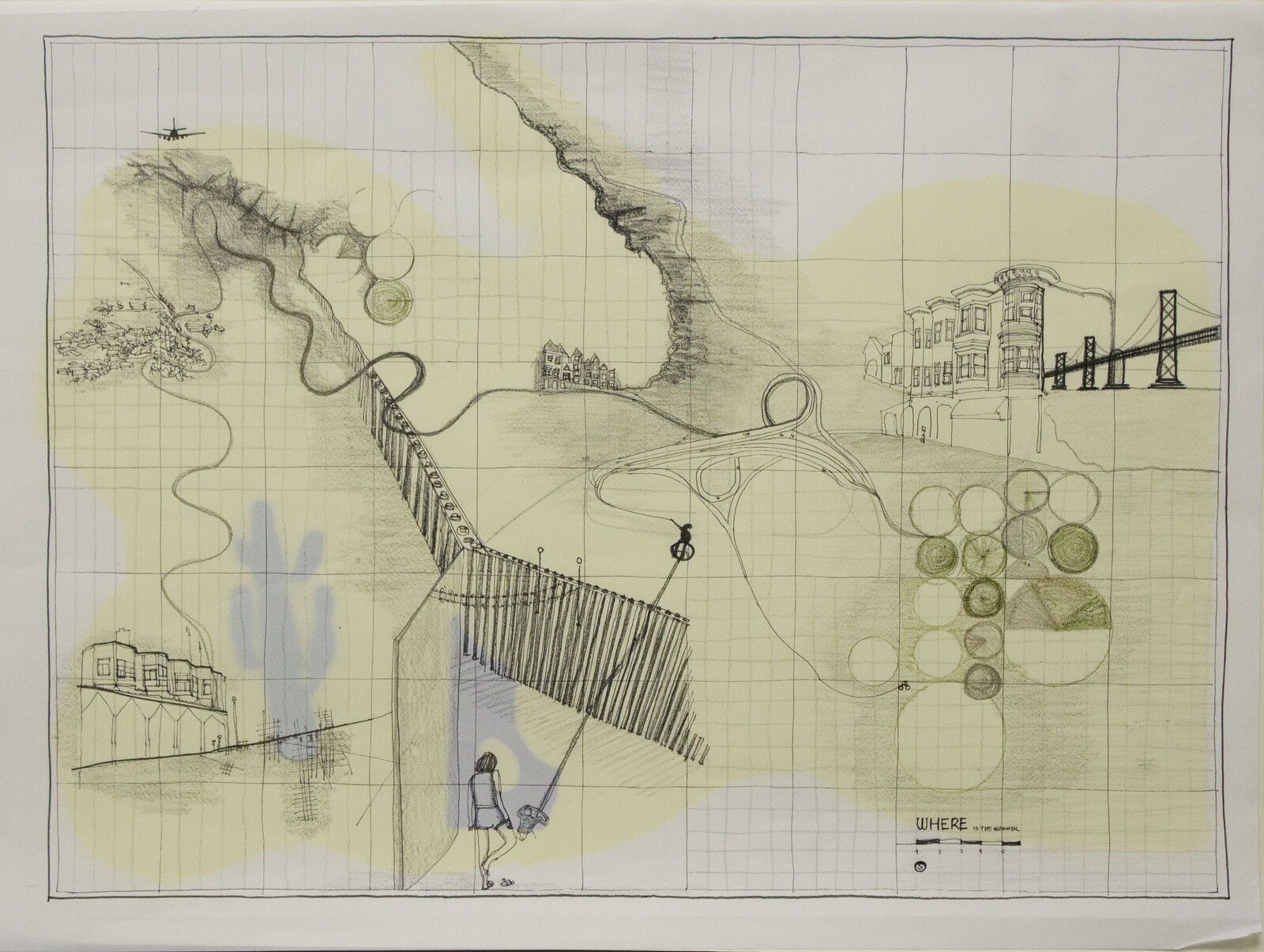

On February 27, 2020 Ned Norris, Chairman of the Tohono O’odham Nation, addressed the United States House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security concerning the destruction of sacred sites on traditional O’odham land. That same day, the US Army Corps of Engineers and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) blew up an O’odham burial site— Monument Hill—to make way for the border wall.1 This event—which took place in a national park, in a UNESCO biosphere reserve, on O’odham traditional land—is one particularly violent instance of dispossession and destruction in the name of “national security.” And it is, of course, no isolated incident. The border wall, the destruction it requires, and the suspension of law that it brings are part of a much broader and more networked infrastructure of militarization in the borderlands. This infrastructure, at once material, legal, and ideological, is the outcome of a recent border strategy that has pushed migrants from urban crossings into dangerous desert terrains and deployed an expansive suite of military technologies to control a perceived inhospitable territory.2 But it also arises out of a centuries-long pattern of federal incursion into indigenous territories. Seen in this light, the border wall is perhaps the most spectacular symbol of an ongoing settler colonial project to expropriate Indigenous land, undermine Indigenous sovereignty, and dictate what that land means and how it is used.

Like all infrastructure, the border wall is networked across time and space, connecting to many other, less visible instruments of securitization. This moment of simultaneity—in which Ned Norris denounced to congress the damage the wall has wrought to “religious, cultural, and environmental resources on which [Tohono O’odham] members rely and which make our ancestral land sacred to our people,” and in which Customs and Border Protection convened a press conference to witness the destruction of that very ancestral land—linked state epistemic violence to violence on land and on bodies. As a burial site, Monument Hill is a place profoundly connected in the O’odham traditional landscape and cosmography. Yet it is now also a site connected to an existing landscape of surveillance on O’odham land.

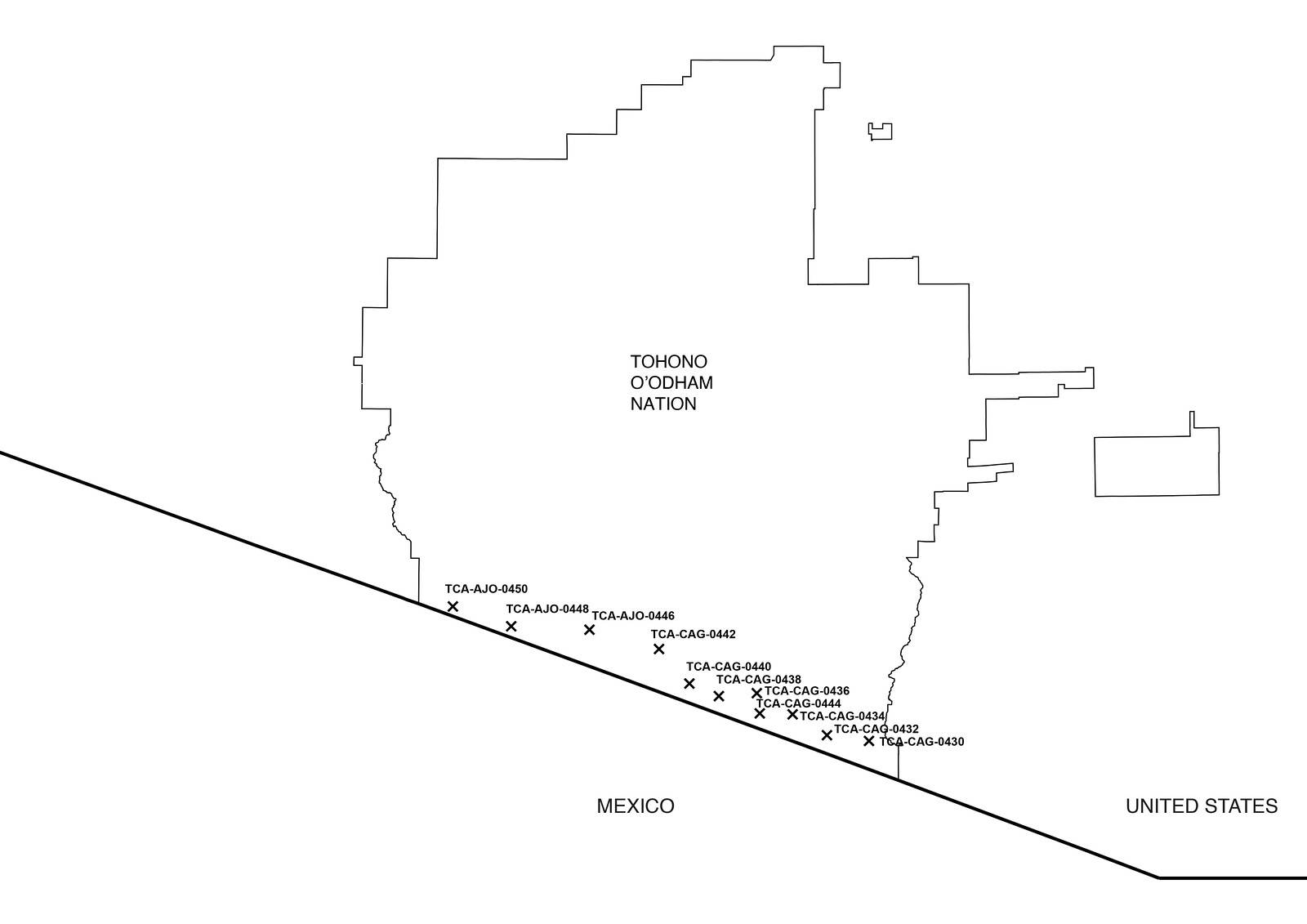

Roughly eighty miles of west of Monument Hill, CBP is laying the foundation for an Integrated Fixed Surveillance Tower (IFT), one of ten to be built on the nation. In March of 2019, the Tribal Council of the Tohono O’odham Nation approved the construction of the ten IFTs along the Nation’s southern border, a boundary that also divides the United States and Mexico. The approval came following five years of negotiation between the tribal government and US Customs and Border Protection, in the face of widespread opposition to the towers, under the pressure of a looming border wall, and after the issuance of a 2017 Environmental Assessment stating the surveillance towers would have “no significant impact” on “the quality of the human or natural environment” of the Tohono O’odham Nation. But border securitization has already had serious impacts on daily life for O’odham people, whose lands span the international boundary and who have historically moved fluidly across it.

The impacts of surveillance infrastructure become even more far reaching when considered through an O’odham understanding of the land and its meaning. Unlike the western scientific framework of the Environmental Assessment, which separates human life from plants, animals, and cultural artifacts, from the O’odham perspective, it is impossible to separate the cultural, ecological, and social effects of this infrastructure. Sacred sites, migration routes, seasonal cycles, genealogy, and sovereignty are interconnected. In the words of tribal elder and activist Ophelia Rivas, “Land has always been defined by Europeans as property. [CBP] have a different perspective on land, and so from that perspective, it’s very difficult for them to understand our relationship to it. I’ve seen the reaction of the border patrol when we talk about our land and how we’re connected to it.”3 Here, in a reservation on a border, imposed on a people whose lands span across geopolitical boundaries, integrated fixed towers are an infrastructure that orders sovereignty, mobility, and land itself. Opposition to them is an act of refusal against the imposition of sovereign control of the state in Indigenous lands and an assertion of the right of Indigenous peoples to regulate movement within their lands on their own terms. It is also an indictment against the broader system in which they operate—a securitizing infrastructure that includes policing and surveillance already installed on the nation (checkpoints, new roadways, increased officers on the ground, detention centers, sensors, and more) and that is connected to a long history of federal attempts to control and expropriate indigenous land in this region.

Chairman Norris was well aware of this history, and its bearing on the possible future for the nation, when he addressed the House Committee:

The Tohono O’odham Nation is a federally recognized tribe with more than 34,000 enrolled Tribal citizens. Our ancestors have lived in what is now Arizona and northern Mexico since time immemorial. Without consideration for our people’s sovereign and historical rights, in 1854 the international boundary was drawn through our ancestral territory, separating our people and our lands. As a result, today the main body of our Reservation shares a sixty-two-mile border with Mexico—the second-longest international border of any tribe in the United States, and the longest on the southern border. On the other side of the border in Mexico, seventeen O’odham communities with approximately 2,000 members are still located in our historical homelands. O’odham on both sides of the border share the same language, culture, religion, and history. Our Tribal members regularly engage in border crossings for pilgrimages and ceremonies at important religious and cultural sites on both sides of the border. We also cross the border to visit family and friends. Today only a portion of our ancestral territory is encompassed within the boundaries of our current US Reservation. Our original homelands ranged well beyond these boundaries, and included what is now the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (adjacent to the western boundary of the Nation’s Reservation), the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge to the east. The Nation has significant and well-documented connections to these lands and the religious, cultural, and natural resources located there.4

Given this history, Norris sees the wall as an imminent threat that will soon advance from Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument east onto the Nation. And it is this threat that the Department of Homeland Security used to pressure an agreement on the Integrated Fixed Towers. According to statements by the prior Vice Chairman of the Nation, the towers were seen as compromise with DHS to prevent the border wall being built on O’odham land.5

2. Territory

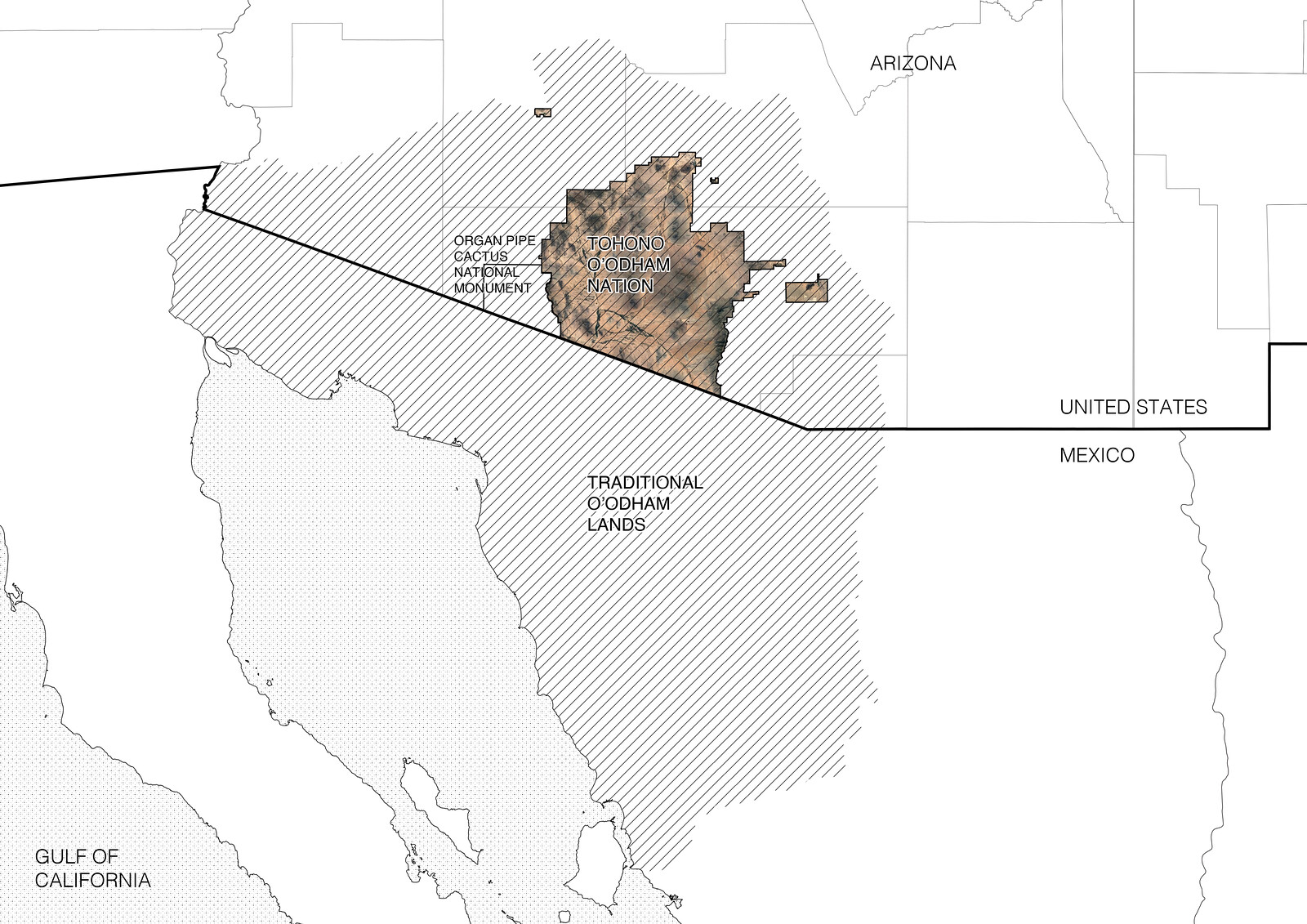

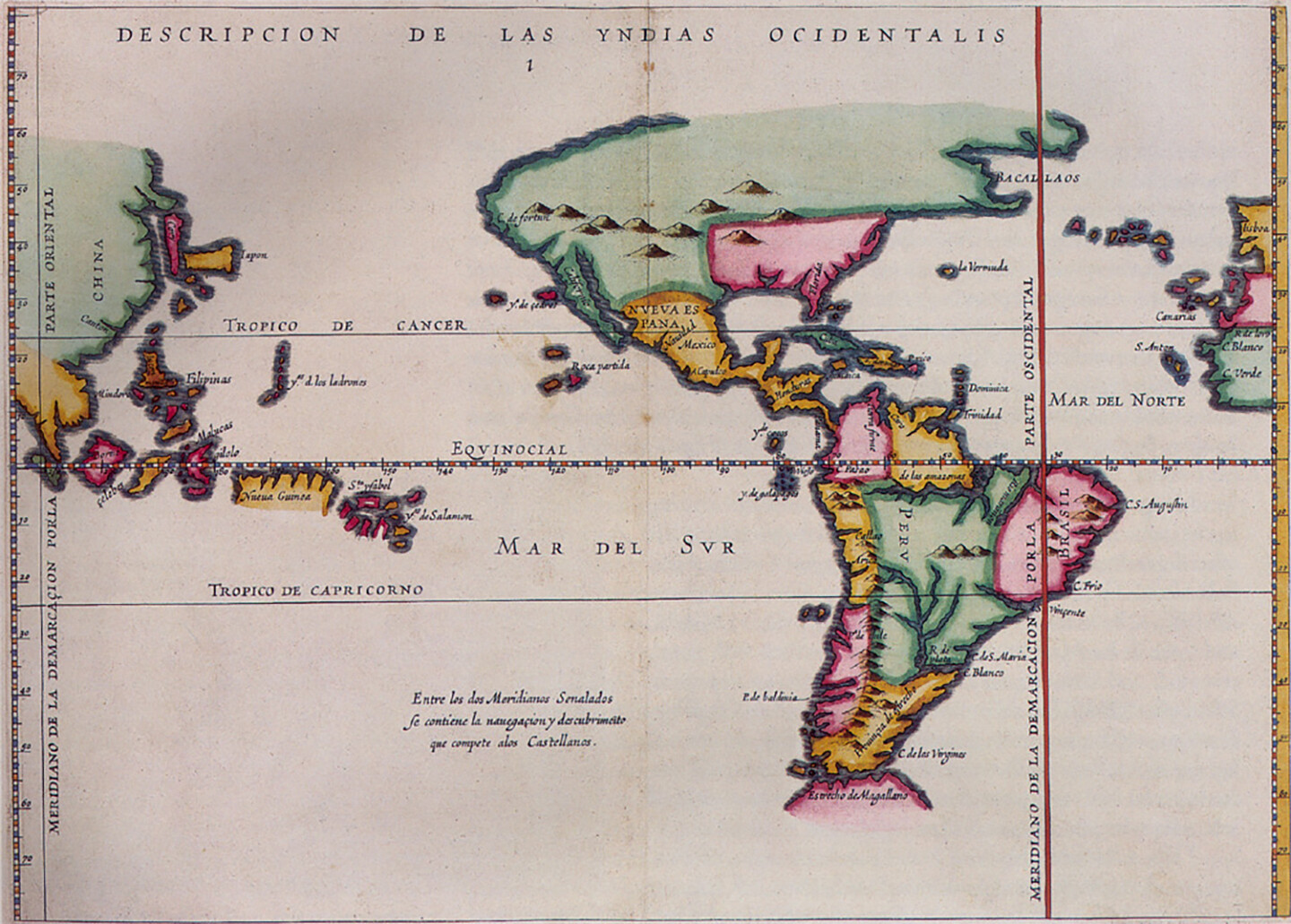

O’odham traditional lands extend from the area around what is now Phoenix in the north, to Douglas, Arizona in the east, down to the Gulf of California. The Tohono O’odham Nation today is but a fraction of that ancestral territory. Following the Gadsden Purchase of 1854, which annexed 30,000 miles of Sonora, Mexico, to the United States—including O’odham territory—the US government established two O’odham reservations in San Xavier and Gila Bend. 1887 marked the passage of the Dawes Act, which allowed the federal government to break up land on reservations held in common and divvy it into individual parcels granted to tribal members listed on official “rolls.” Remaining lands were open to settlers. While this did not happen on all reservations, Tohono O’odham lands were opened to allotment in 1888. In 1916, in response to the Mexican Revolution and Pancho Villa raids, the government created the Sells Reservation, now called the Tohono O’odham Nation, and built the first US-Mexico border fence on it.6 Then the fear was Mexican revolutionaries coming north into the United States, but implicit too was a need to imprint the idea of the American nation-state onto people for whom the border did not matter. Thus began a history of federal incursions onto O’odham land in the name of defining and securing national property, and hence national sovereignty. The division of reservation land into allotments of private property has made it easier for the US government to claim eminent domain on non-allotted land within the reservation—which it has historically done to build infrastructure.7 Furthermore, the title to Native American reservation land is held in trust by the Federal Government, making it easy for the state to expropriate land for federal projects, or waive certain laws that apply to public lands.

Until recently, CBP viewed the desert as a hot, inhospitable expanse—a natural barrier too harsh and depopulated for many migrants to travel. From the 1990s onward, the Department of Homeland Security’s Operation Gatekeeper used the perceived unknowability and danger of this terrain to funnel border crossing towards urban areas, or toward the eastern segment of the Rio Grande where surveillance infrastructure was more robust.8 The desert became a topoclimatic device to channel the flows of migrants. Yet, as fears of drug trafficking increased during the Obama administration, and anti-immigrant rhetoric accelerated to fever pitch under Trump, the Sonoran Desert transformed from an “empty” terrain of deterrence into one of apprehension and fortification.

With the 2001 Patriot Act, crossing the US-Mexico border along the Tohono O’odham nation was restricted to three “tribal gates.” Customs and Border Patrol manages these checkpoints where sufficient documentation—such as a passport or tribal ID, which many O’odham in Mexico do not have—is needed to cross. Crossing along ceremonial and informal paths was made illegal. The transformation of tribal gates into checkpoints has turned traditional pathways through contiguous territory into sites of encounter with state control, where CBP has to be notified ahead of time to come check documents of O’odham tribal members. This not only adds layers of state bureaucracy to routine movement, but also discourages the act of border crossing and criminalizes it for those who do not conform to the new laws. O’odham in Mexico are often unaware of these laws and can end up being apprehended, deported, and told they may no longer cross into their lands within what is now the United States. Here border infrastructure criminalizes indigenous land use and annuls claims to sovereignty on the part of residents on both sides of the geopolitical boundary.

In 2011, the US Department of Homeland Security implemented the Arizona Border Technology Plan, which planned for the deployment of tower-mounted radar, cameras, and communication equipment—both mobile and fixed—as well as ground sensors along the US-Mexican border in Arizona to assist Border Patrol with monitoring and apprehension. In 2014, the Southwest Border Technology Plan expanded the intensification of border surveillance to the rest of the southwest border. These border technology plans expanded the constricted mobility already in place as the result of border checkpoints and stops. Integrated Fixed Towers and the equipment they carry constitute a more pervasive form of monitoring and control—what CBP refers to as “persistent surveillance.”9 Both tribal gates and Integrated Fixed Towers impinge on movement and undermine Indigenous territorial sovereignty.

It’s no coincidence that the proposed construction of towers coincides with the addition of detention facilities for people apprehended crossing the border. It also requires little stretch of the imagination to understand that the infrastructure apparently needed to support the construction and maintenance of towers (the truck paths latticing the desert, the movement of Border Patrol Officers to nearby stations, the tracts of housing and trailers of mobile offices) are also quite useful in the pursuit of what the Environmental Assessment terms “items of interest”—be they local residents, US citizens, or migrants entering the country legally or illegally. They are also part of a sustained harassment of the permanent population in the borderlands, facilitated through the establishment of the so-called 100-mile border zone, adopted by the US Department of Justice in 1953. While the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution protects Americans from random and arbitrary stops, it does not fully apply to the 100-mile zone, where regulations allow for border agents to conduct what courts have called a “routine search without a warrant or even suspicion.”10

Harassment on the Tohono O’odham Nation is exercised at increasing scales, sometimes erupting into lethal violence. In addition to the CBP-regulated gates on the border itself, officers at checkpoints at the Nation’s borders with Arizona stop O’odham systematically. CBP pull people over at random who are driving on the reservation, raid their homes to see if they are helping migrants, and even draw guns on children running outside. They also have run over community members with patrol vehicles multiple times.11 With something close to one CBP agent for every ten registered tribal members, the land feels occupied, saturated with CBP agents and equipment. Both land and people are treated with hostility. This “persistent surveillance” and its pattern of harassment creates an infrastructure of state violence in which border militarization and policing of Indigenous populations reinforce one another.

The Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, a 517-square-mile National Park to the west of the Nation, became a testing ground in this territorial transformation in the years after the passage of the Patriot Act. Established in 1937 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Organ Pipe National Monument required a careful construction of boundaries to redefine an ecological landscape free of human settlements and use. The Monument was established on O’odham homelands, and like many early US national parks, justified dispossession of Indigenous peoples through its preservation ethos. As described by anthropologist Jessica Piekielek, in order to create a controlled parkscape reserved for the flourishing of native fauna and flora and touristic leisure, in the 1940s and 1950s the National Park Service and Monument staff drew on resources made available through cooperating with federal agencies charged with enforcing the national border.12 In an attempt to control ranching, the trespass of livestock, as well as hunting and wood gathering, the National Park Service collaborated with the Bureau of Animal Industry and the International Boundary and Water Commission in 1949 to establish a fence along the entire length of the Organ Pipe’s southern boundary, a time when much of the southwestern border was still unfenced. Next to the establishment of a physical border, the Bureau of Animal Industry also established several camps along the Monument’s border to Mexico to run horse patrols. The first in a series of projects by the National Park Service with other federal agencies to fence the Monument against “foreign” intrusion, its administration actively contributed to the hardening of the national border and attempts to stop a cross-border culture.

This pattern of border securitization on Organ Pipe continued throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. As CBP was tightening its grasp on border city bottlenecks in Nogales and Yuma during Operation Gatekeeper (1994–1997), migrants were funneled toward the national park from where they would often enter the Nation seeking food and assistance. This collusion between the US Border policy and preservation practices therefore created the “high risk” situation in the Nation that today necessitates a “persistent surveillance” infrastructure. In 2003, this situation was amplified when the National Park Service closed Organ Pipe following the 2002 shooting of a park ranger; it was soon after declared the “most dangerous national park.”13 During Organ Pipe’s closure from 2003 to 2014, CBP built a vehicle barrier along the entire extent of the international boundary within the park, and erected several mobile surveillance towers near the border as well as at the very northern edge of the park abutting the Tohono O’odham Nation. In 2014, when Organ Pipe reopened, CBP proposed sixteen IFTs in the Nation, including eight along the border with the park (not Mexico), connecting to the mobile towers already installed there.

While the National Park Service’s jurisdiction over this territory has facilitated the development of the Southwest Border Technology Plan and opened up access and information sharing for CBP, it has created a bureaucratic barrier for O’odham people trying to use their traditional lands. As Ophelia Rivas explains, “Normally we do not need permission or paperwork to do our ceremony on O’odham lands. But when we have to go into Organ Pipe National Monument, we need to notify someone and we need to do the paperwork. So that is a hinderance… People stopped going there, because we were not allowed to build a fire on the ground, which is a part of ceremony … that is the connection to the land.”14

In an interview, superintendent Ranger Brent Range touted the close and collaborative working relationship the park has with the Department of Homeland Security.15 It’s a relationship that was undoubtedly enriched through a decade of collaboration over border infrastructure, but that also predated the closure of the park. As Rick Felger, Director of Natural Resources, told us, the park works closely with the border patrol when agents find “cultural artifacts”—which is to say, O’odham artifacts—and are required by the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) to consult with the Organ Pipe archeologist and the National Park Service’s regional conservation center in Tucson. The National Historic Preservation Act was waived, however, as part of the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which repealed environmental laws and created the pathway for waivers to be issued to facilitate the installation of “additional physical barriers and roads (including the removal of obstacles) in the vicinity of the United States border.”16 The NHPA is also the framework used in the 2017 Environmental Assessment to determine Integrated Fixed Towers have no significant impact on cultural sites, contradicting the concerns of O’odham tribal members.

3. Towers

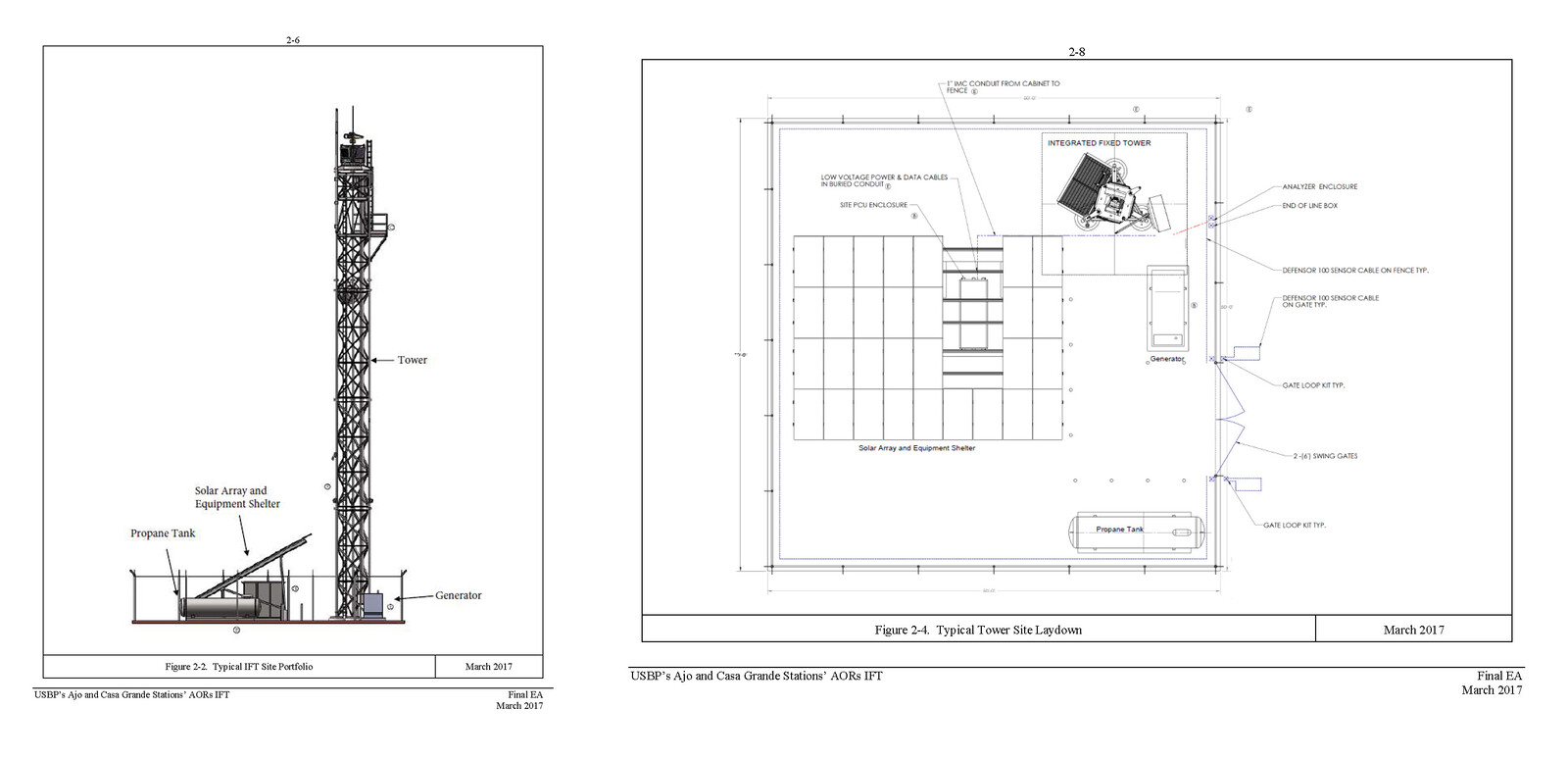

Trussed columns standing 120–180 feet high, Integrated Fixed Towers are mounted with surveillance equipment at the top and include a base with a propane tank, generator, solar panels, and equipment shelter. Their footprint is anywhere from fifty-by-fifty to 160-by-160 feet wide and includes a parking area. They are surrounded by a fence that enclose up to 10,000 square feet, and a thirty-foot wide fire buffer beyond that where all vegetation is cleared. Tower access also includes seventy miles of new and widened access roads along with drainage ditches. They are also hooked up to the grid, necessitating new power lines and fiber optic cables.17

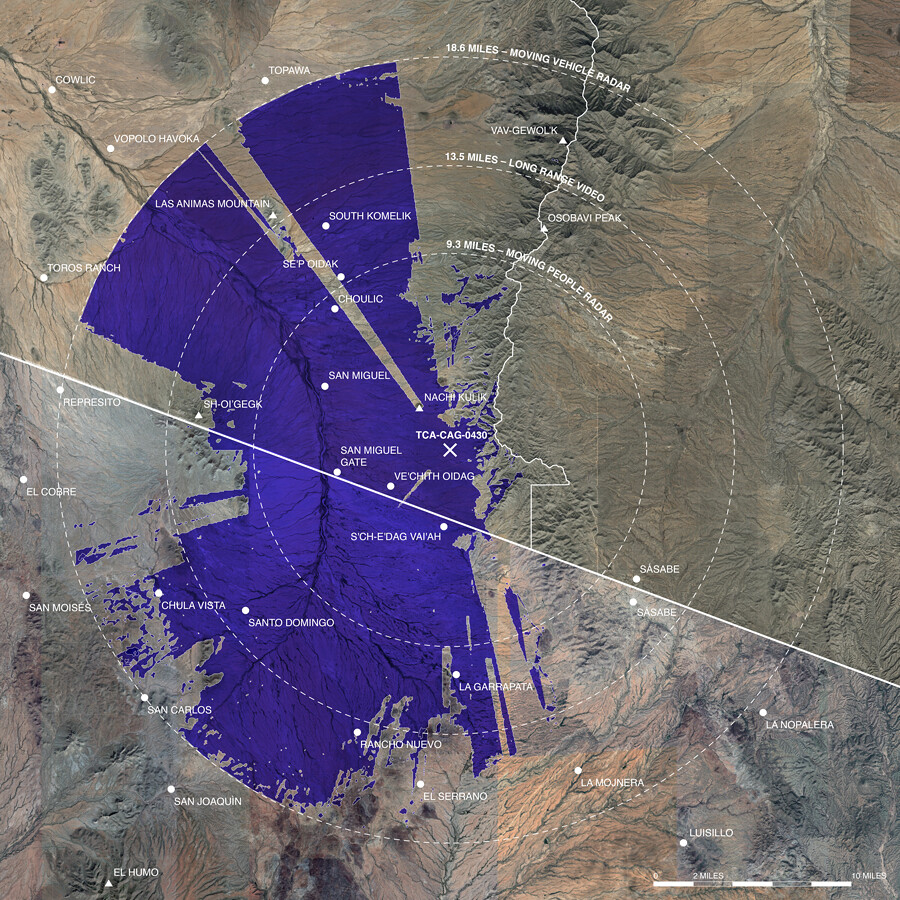

But the real footprint of the towers extends beyond the perimeter of the fence, and even beyond the roadways that connect to it. Outfitted with a range of surveillance equipment designed to identify and classify “items of interest” near the border, their radio-frequency radar can detect moving bodies within a 9.3-mile radius, long-range video cameras can capture everything within a range of 13.5 miles, another radio-frequency radar can detect moving vehicles within an 18.6-mile radius, and microwave communication receivers that transmit up to forty miles. In addition to that, they hold spotlights and laser illuminators for night operations. The reach of these technologies extends far beyond the border into O’odham lands in Mexico.

According to Ophelia Rivas:

[The way we see land] seems not to make a difference to [CBP] that it’s of great concern to us. It’s very disturbing to the people who continue to follow that ceremony way of life… When I grew up, I climbed all these mountains and we ran and played all over. There were also people crossing the border that were undocumented. There was always drug trafficking, but we played everywhere. And now the kids are just stuck in their homes. It changed our whole way of life. Ever since this constant surveillance began. When it began after 9/11, it was so aggressive that it forced the people not to go out on the land anymore. That is really affecting the health of everybody. The health of the elders—who really need to be out on the land to connect with the plants and with the mountain. From that point on, the children don’t see their elders out there, they’re not connecting to that part of our life. This forced disconnection to the land is unhealthy because with the disconnection they lose their language, traditional diet, and sensitivity to turn to traditional medicine.18

Apart from the immediate consequences of surveillance, fear and intimidation have pushed community members into their homes, spaces defined as private property by western frameworks, which has longer-term effects—damaging an intergenerational connection to land and cultural practices and infringing on practices of hospitality. Rivas adds, “We are criminalized for having brown skin and dark hair when we never regarded any human as being illegal. The people crossing the O’odham lands were always treated as human and not as trespassers.”19

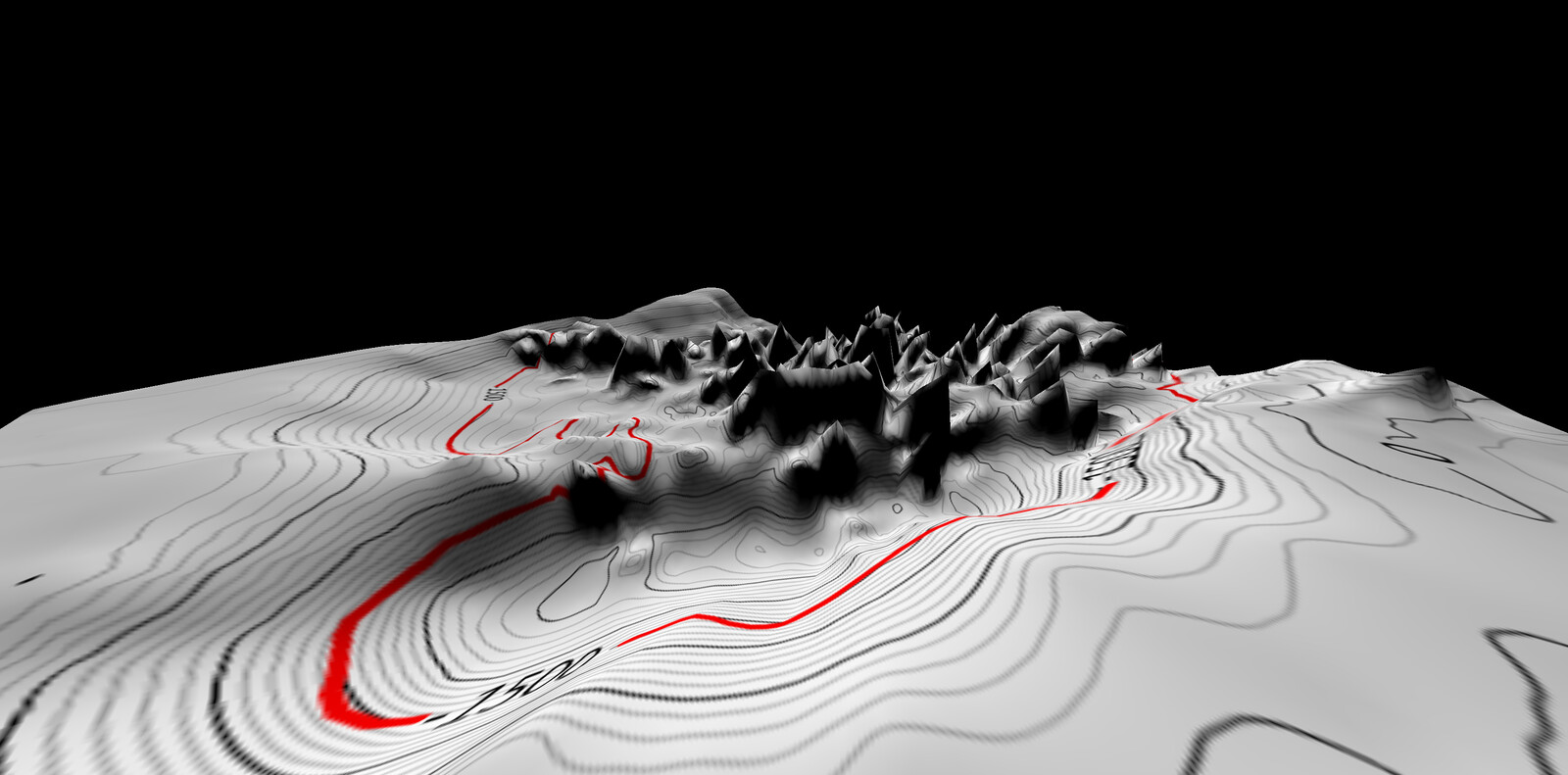

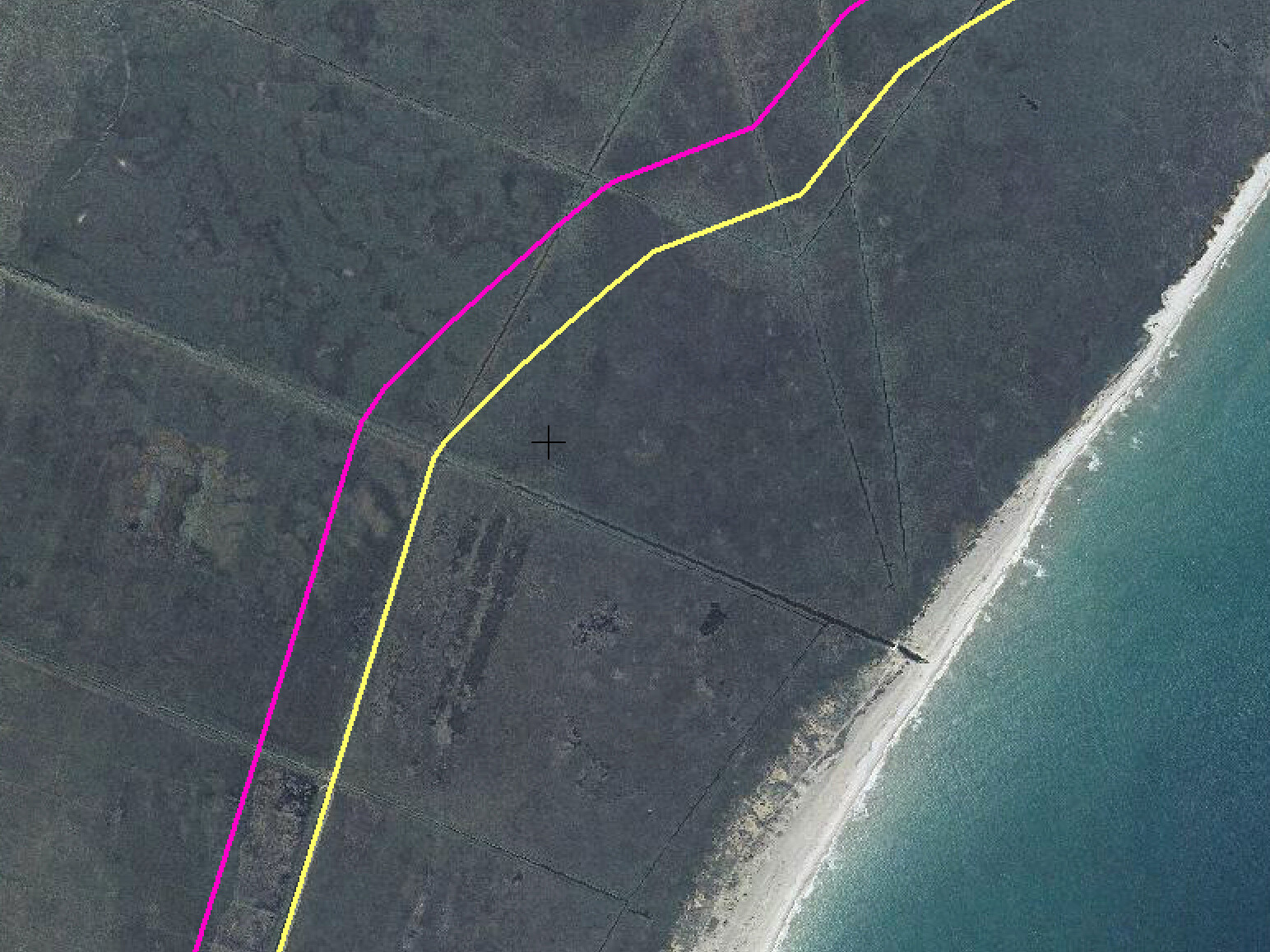

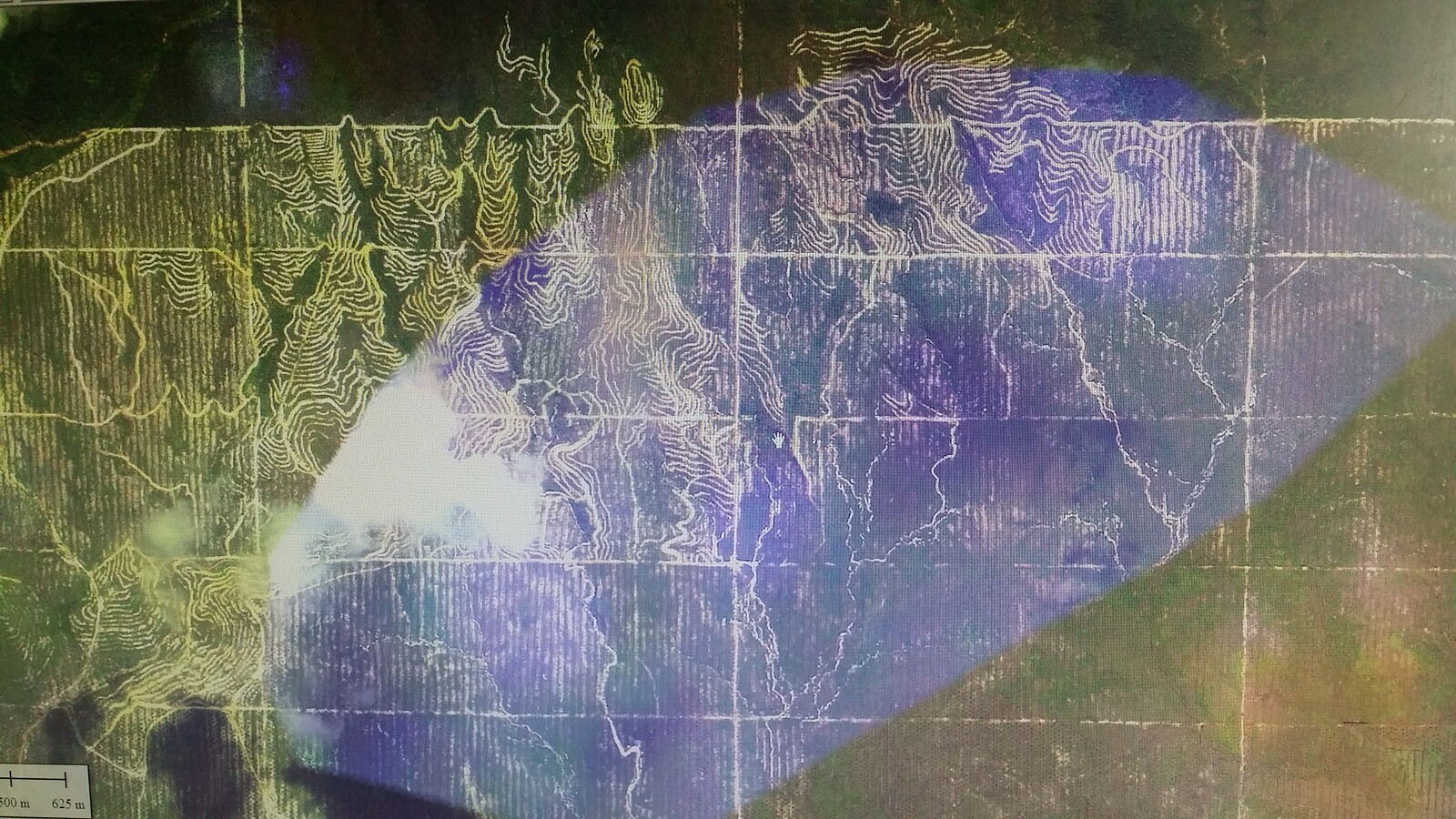

Map indicating surveillance equipment radii and reach of TCA-CAG-0430, the first tower currently erected at Chukut Kuk District, Tohono O’odham Nation. Drawing: Caitlin Blanchfield and Nina Valerie Kolowratnik. Surveillance equipment represented in the map: radio-frequency radars for tracking moving people [9.3 mile radius] and moving vehicles [18.6 mile radius] as well as long-range video cameras [13.5 mile radius]. The 40-mile radius of the microwave communication receivers exceeds the boundaries of this map and is not shown. While type of surveillance equipment to be installed and surveillance equipment companies to be contracted or subcontracted have been made public, the exact equipment models to be used have not. The map is based on the most powerful surveillance equipment from companies to be contracted or subcontracted.

Though construction has just begun, one can already see the infrastructural reach of these towers at work. A new roadway built for the construction of one IFT, TCA-CAG-0430, has uprooted protected saguaro, prickly pear cactus, and ironwood, among other plants that are important for O’odham medicines and traditional foods. The towers also extend the reach of border patrol into O’odham communities and make it easier for them to patrol in remote areas, as evidenced when together with Rivas, we were pulled over on a recent trip to document tower construction. These roadways link tower sites to staging areas—locations where construction equipment and mobile offices are located. Water tankers, backhoes, excavators, compactors, semi-trucks, port-a-potties, and trailers fill the staging area by the San Miguel gate just a few yards from the border fence. This staging area is a residue of the border fence project, originally created for its construction. In its Environmental Assessment, CBP writes that it will rely on existing staging areas located in “disturbed areas” to store materials and equipment.20 This, it would seem, is what “no significant impact” looks like—reinforcing and extending “disturbed areas” and establishing their utility for future border construction projects.

Staging areas are located within another specific jurisdiction of exception: the Roosevelt Reservation. The Roosevelt Reservation is a sixty-foot-wide strip of land running alongside the international boundary on public lands in California, New Mexico, and Arizona. Created by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907, this strip is “reserved from the operation of the public land laws and kept free from obstruction as a protection against the smuggling of goods between the United States and said Republic [of Mexico].”21 An underdiscussed policy and spatial product, the Roosevelt Reservation is now what is being used to build border infrastructure. Because Native American reservations are held in trust by the federal government, this sixty-foot-strip of territory can be easily requisitioned for whatever purpose DHS deem necessary, which so far has meant vehicle barriers and border patrol roads dividing O’odham lands.

By deploying this sixty-foot-margin of land across the sixty-two-mile border the O’odham reservation shares with Mexico, DHS mobilizes the very terrain of the O’odham territory to disrupt the connectivity and mobility of its people. At the same time, the Roosevelt Reservation enables an infrastructure of surveillance and exceptionality. “Infrastructure,” writes Hannah Appel, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta, “of course mediates time as much as it mediates space. Infrastructures configure time, enable certain kinds of social time, while disabling others and make some temporalities possible while foreclosing others.”22 In conjunction with other legal documents such as the IIRIRA and its capacity to suspend environmental conservation laws, the Roosevelt Reservation creates a temporality of crisis, threat, and emergency, one that has foreclosed O’odham connection to their lands and severed cyclical patterns that link locations on both sides of the border through ceremonies or harvests.

Ned Norris stated that “DHS has used IIRIRA self-waiver authority to avoid more than forty-two laws that otherwise would protect the rights of individuals and local governments, private property rights, water rights, religious practices and culturally sensitive sites, the environment, endangered species, and a host of other rights and resources that Americans—and the Tohono O’odham Nation—hold dear.”23 The waiver constitutes part of a securitization infrastructure that is temporal, territorial, and epistemological. It is, as J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, discussing the work of Patrick Wolfe, describes, “a structure, not an event,” in an ongoing process of settler colonialism. In an article on Wolfe’s notion of settler colonialism as a structure, Kēhaulani Kauanui also describes “enduring indigeneity,” a term of dual implications: “that indigenous peoples exist, resist, and persist; and second, that settler colonialism is a structure that endures indigeneity, as it holds out against it.”24

It is in the face of this double-sided endurance that Tohono O’odham elders and activists have fought against and still oppose Integrated Fixed Towers and the militarization of their lands more broadly. In this sense, we might also understand their refusal to accept the terms by which the Department of Homeland Security defines ideas like “environment” and “impact” in relationship to land, living things, and culture, as an act of sovereignty. “Refusal,” writes Audra Simpson, “comes with the requirement of having one’s political sovereignty acknowledged and upheld, and raises the question of legitimacy for those usually in the position of recognizing.”25

Refusal is a complex and complicated action. The Nation is dependent on the federal government for funding, which compromises their position of opposition and likely led them to approve the IFTs. There are many political divisions within districts where towers are being built, and misinformation has been spread by CBP, which told people they would get better wifi and repaved roads. However, the number of towers was reduced from sixteen to ten, indicating that opposition does have an effect. As Ophelia Rivas reminds us, the land lease for the towers is twenty-five years long. Continued opposition and vigilance is important not only to pushback against militarization in the present, but to dismantle it in the future.

“The Testimony of the Honorable Ned Norris Jr, Chairman to the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Homeland Security Subcommittee on Border Security, Facilitation and Operations Hearing Examining the Effect of The Border Wall on Private and Tribal Landowners,” February 27, 2020, ➝. Ryan Deveraux, “The Border Patrol Invited the Press to Watch it Blow Up a National Monument,” The Intercept, February 27, 2020, ➝.

Here we refer to, among other policies, the Southwest Border Technology Plan, the Southwest Border Strategy, and Operation Gatekeeper.

Interview with Ophelia Rivas, December 13, 2016.

“The Testimony of the Honorable Ned Norris Jr,” ➝.

Molly Hennessy-Fiske, “Arizona tribe refuses Trump’s wall, but agrees to let Border Patrol build virtual barrier,” the Los Angeles Times, May 9, 2019.

For more on the history of the Tohono O’odham borderlands see Geraldo L. Cadava, “Borderlands of Modernity and Abandonment: The Lines within Ambos Nogales and the Tohono O’odham Nation,” Journal of American History 98, no. 2 (September, 2011): 362–383.

On the relationship between the history of federal infrastructure projects, current neoliberal infrastructure projects, and indigenous resistance see Nick Estes’s recent book on the Dakota Access Pipeline and the Standing Rock water protectors. Nick Estes, Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (New York: Verso, 2019).

Joseph Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Remaking of the US–Mexico Boundary (New York: Routledge, 2001).

“Final Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation in the Ajo and Casa Grande Stations’ Areas of Responsibility; U.S. Border Patrol Tucson Sector, Arizona; U.S. Customs and Border Protection Department of Homeland Security Washington D.C.,” (April 2017), 11, ➝.

ACLU, “Constitution in the 100 Mile Border Zone,” ➝.

Some of these instances were recounted to us by community members. More information on Border Patrol violence, and the hit-and-runs specifically, can be found on the webpage of O’odham activist group TOHRN, ➝. See also John Washington, “‘Kick Ass, Ask Questions Later’: A Border Patrol Whistleblower Speaks Out about Culture of Abuse against Migrants,” The Intercept, September 20, 2018, ➝; and Bayan Wang, “‘Justice Needs to be Done’: Mom of Man in Video Showing Border Patrol SUV Strike Him,” AZCentral, June 16, 2018, ➝.

Jessica Piekielek, “Creating a Park, Building a Border: The Establishment of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and the Solidification of the U.S.-Mexico Border,” Journal of the Southwest 58, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 1-28.

Tim Gaynor, “Arizona Border Park Once Deemed ‘Most Dangerous’ in US Reopens to Public,” Al Jazeera, April 23, 2015, ➝.

Interview with Ophelia Rivas, March 12, 2017.

Interview with Organ Pipe National Monument Superintendent Brent Range, March 14, 2017.

Federal Register 73, no. 68, April 8, 2008, 19077.

“Final Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation in the Ajo and Casa Grande Stations’ Areas of Responsibility,” ➝.

Interview with Ophelia Rivas, December 13, 2016.

Interview with Ophelia Rivas, December 13, 2016.

“Final Environmental Assessment for Integrated Fixed Towers on the Tohono O’odham Nation in the Ajo and Casa Grande Stations’ Areas of Responsibility,” 36, ➝.

Theodore Roosevelt, Presidential Proclamation (35 Stat. 2136), 1907.

Hannah Appel, Nikhil Anand, and Akhil Gupta, “Temporality, Politics, and the Promise of Infrastructure,” in The Promise of Infrastructure (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2018), 15.

“The Testimony of the Honorable Ned Norris Jr,” ➝.

J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, “’A structure, not an event’: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity,” Lateral 5, no. 1 (2016).

Audra Simpson, Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across Settler States (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 11. Italics in the original.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.

Category

Subject

Research for this article was conducted in collaboration and conversation with Tohono O’odham Tribal Elder and activist Ophelia Rivas.

At The Border is a collaboration between A/D/O and e-flux Architecture within the context of its 2019/2020 Research Program.