Artificial Labor is a new collaborative project between MAK Wien and e-flux Architecture within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017 and its theme, “Robots. Work. Our Future,” featuring contributions by Mario Carpo, Marc Coeckelbergh, Joseph Grima, Harald Gründl, Helen Hester, Axel Kilian, Luciana Parisi, Julia Powles, Patricia Reed, Andreas Rumpfhuber, Bruce Sterling, and Bruce Wexler.

Cedric Price famously stated: “Technology is the answer, but what was the question?” The creative disciplines of art, architecture and design can prove incisive for reflecting upon the urgency of this question today, but where do we begin to comprehend the scope and stakes of contemporary technological development? How can we think to intervene in epistemic transformations currently being performed by computational and robotic industries well beyond the discursive limits of cultural debates?

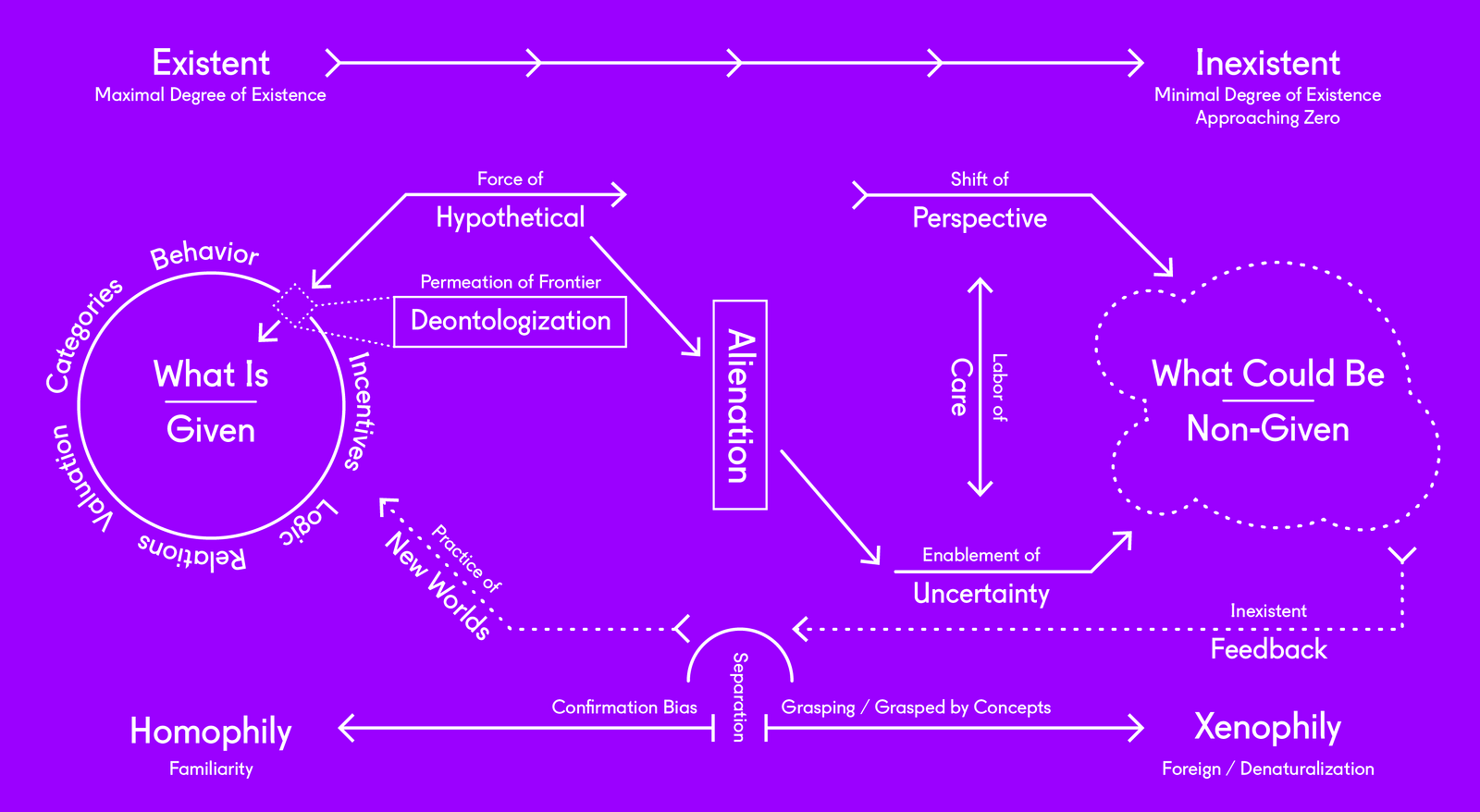

The concept of autonomy is easy to confuse with automation. A core tenet of Enlightenment thinking was that reason and rationality can be considered absolute to the point where law, common sense, morality, and criteria for judgment can be formulated in accordance with their self-evident truths. These laws of the universe supersede human command, so humans would naturally gain their own autonomy and freedom by using reason to design themselves and their world out of these fundamental truths. Natural law would simply be the social program of these truths.

Teleological Kantian views of universal law and truth or morality seem naively absolute in the face postmodern aesthetics, the psychoanalytic unconscious, or pretty much any postcolonial perspective. Even if truth is universally available, it can’t be applied without imposing a specific cultural order or morality, weird historical fetishes, or bureaucratic formalism. But if the autonomy of reason lost its potential for artistic or human emancipation, it is alive and well in artificial or machine intelligence, where, insofar as the rational world can be perceived through sufficient enough real data, it can be designed.

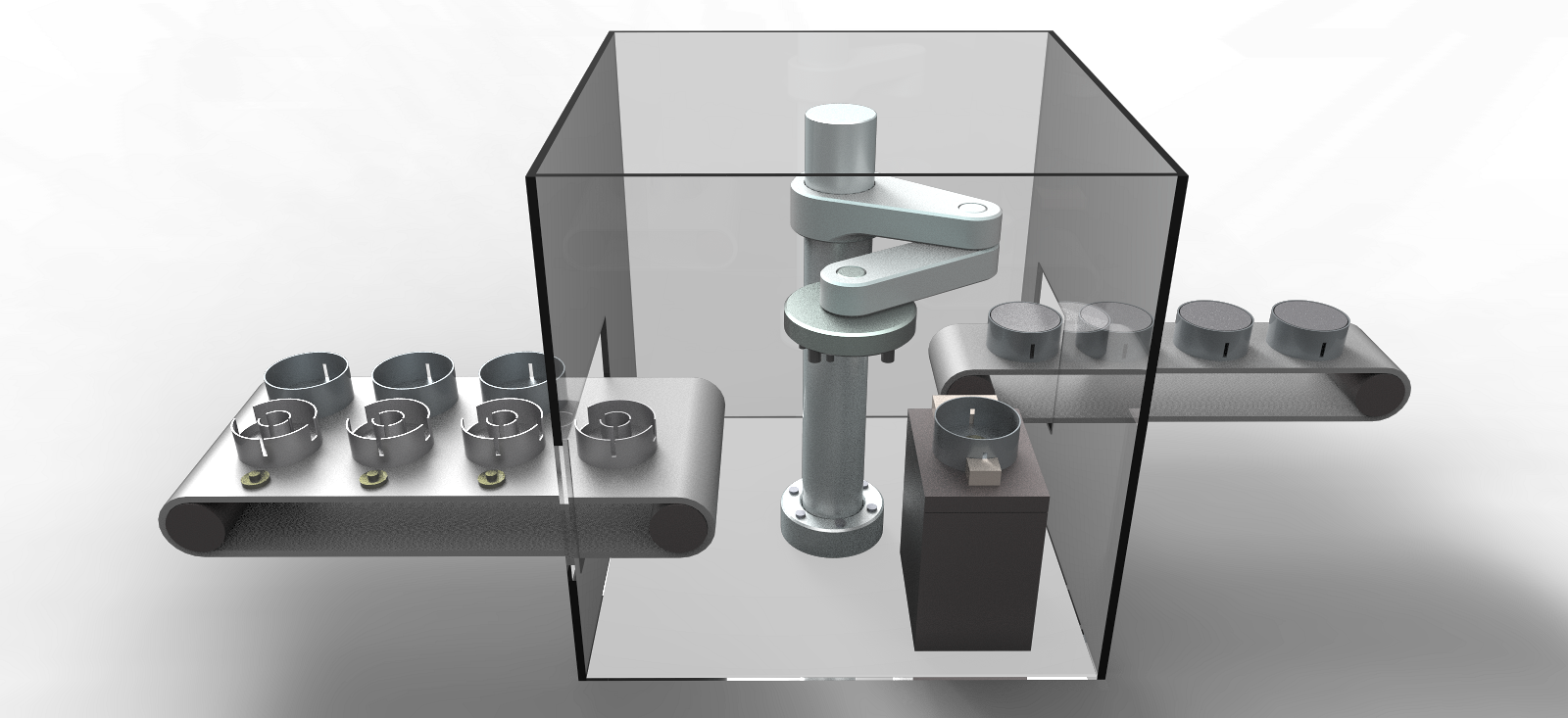

A particular understanding of empowerment thus lies at the root of research into robotics and artificial intelligence. Freedom can, apparently, be engineered. Our cities, our houses, our surfaces are integrating automation so that we may purportedly become more autonomous. The all-encompassing digitization of everyday life currently underway still carries the holistic, just, and humanistic promise of a previous generation, yet the tendencies of its contemporary manifestations increasingly cast doubt on its fulfillment. Automated technologies have been deployed throughout the social and economic sphere since the dawn of modernity, obscuring a common emancipatory horizon by means of a double bind: by giving and taking, liberating and ensnaring, alleviating and obliging. Technological development has an inherently uncertain future, which places focus on the agents and mechanisms of its progress. Opportunity is not destiny, and history, as we know, can go any which way.

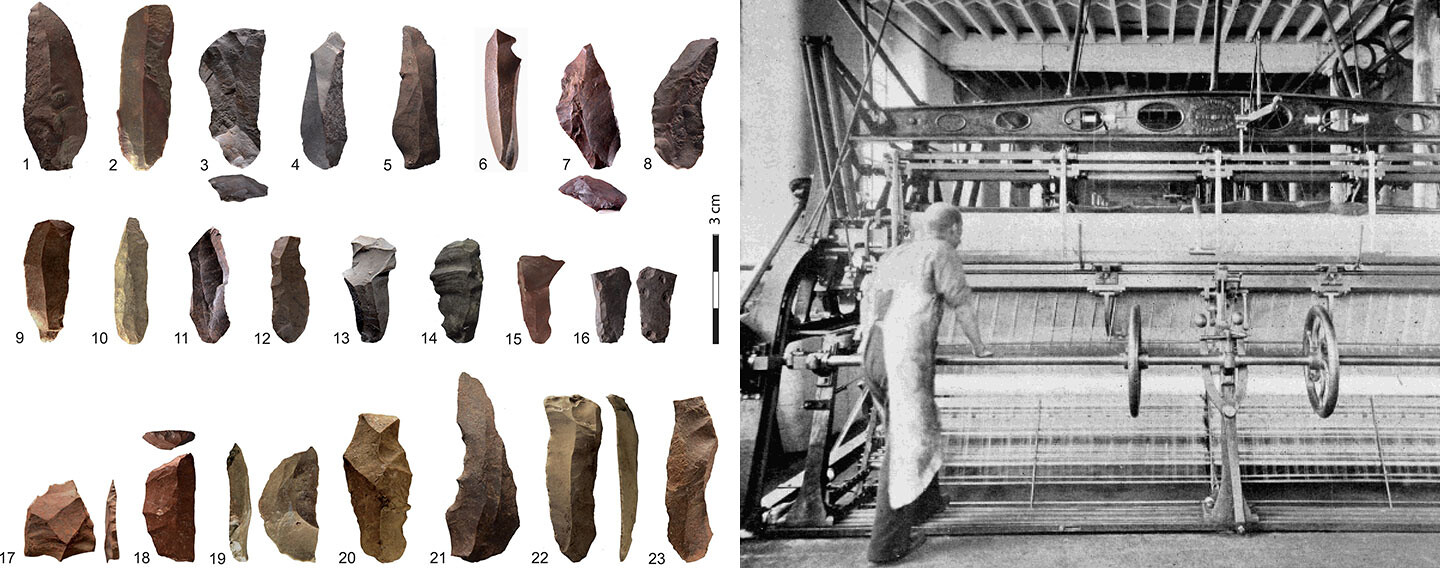

Machines have, we should not forget, long been a figure of the human, an analogue through which we can reflexively learn what it means to be human. Yet contemporary technology seems to have abandoned an ocular ethos of indexical referentiality in favor of a prismatic attitude of uncanny exuberance, challenging inherited epistemic foundations of knowledge, truth, certainty, value, and belief. The portraits being algorithmically manufactured today feel more real not because we give more to work with, but because more can be taken without our notice. Yet if we look beyond the self-image projected onto our retinas and focus our eyes on the surface of technology, what we can see is, at least upon first glance, a picture of the human at work. With the progressive advance of automation into dimensions of life previously unthought, relieving us of duties never before conceived of as such, technology has begun to map out and define the conceptual terrain of labor. We are the frontier. Have we not always been though?

Over the course of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017, architects, designers, philosophers, scientists, writers, and artists will bring new insight to the following, and related questions: Could labor—in both its originary and contemporary plenitude of forms—have been conceived of and critically investigated as such without the historical emergence of its machinic appropriation? What would political concepts such as gender or domesticity have become without the historical invention of technologies for their potential displacement? What new territories for political struggle are being opened, brought to light, and which are being foreclosed, obscured, by the technological progress of today?

Artificial Labor is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and MAK Wien within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017 and its theme, “Robots. Work. Our Future.”

Category

Subject

Artificial Labor is collaborative project between e-flux Architecture and MAK Wien within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017.