The provocation of automation, by whatever technologic means, is not an interface design question. It is not about our experience, or how friendly, human-like or smooth these machines will be. Rather, it is a question of human agglomeration; a provocation to rethink, I argue, housing as a building type dedicated to dwelling. The challenge will be to go beyond the (modern) conception of housing as reproductive space in the face the disappearance of its dialectical opposite: spaces of production. Housing was, at least historically speaking, the response to industry’s promise of leisure. How then are we to live together and interact with one another within an increasingly automated, and thus formally determined, technological environment? The question of technology is not how we might escape it, but rather how we will affirm it and what it portends in relation to the way we dwell and live. In order to be able to answer these questions we must first understand the relationship between housing and labor genealogically, as one that emerged with the advent of industrialization and transformed as the result of post-war economic and urban reorganization. It is only from this perspective that we can grasp what is at stake in the contemporary transition towards an increasingly automated economy and challenge the very idea of housing as a space for living.

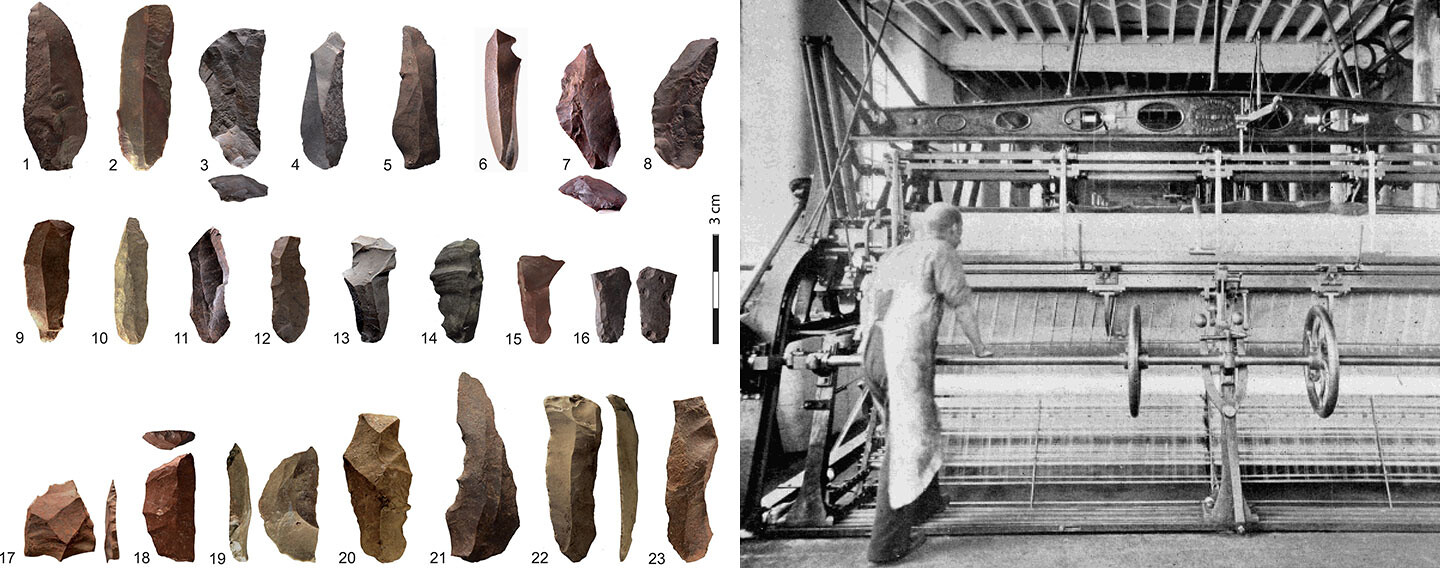

Oskar und Peter Payer, Visualizations of the Municipal Housing Estate “Bundesländerhof” (1962). The visualization clearly shows the programmatic bias of postwar housing as monofunctional leisure neighborhoods. Image: Peter Marchart, “Wohnbau in Wien,” 1923–1983.

Housing

As a modern invention that emerged during the first industrial revolutions to house the working class, housing is as an integral part of capitalist logics vis-à-vis the factory. While seeking to provide appropriate, sometimes even radical and emancipatory solutions to the problem of shelter, housing has always been a spatial instrument of governance. In its aim to make society manageable and calculable, from the very beginning housing both explicated an idea of functional differentiation between productive and reproductive activity—between labor and leisure—and, insofar as its inhabitants were framed into objects of value for the capitalist system, demonstrated a proclivity for becoming subject to commodification. Housing—what has become the anonymous building mass in between the imperial, religious and bourgeois monuments of the city—shapes the appearance and organizes the logics of our cities, ultimately determining how societies are able to form and live.

The industrial revolution’s gradual separation of functional spheres comes to an apogee in 1933 with CIAM’s Charter of Athens and its ideological conception of the “Functional City,” which effectively applied the capitalist logic of dividing work into parts that can be easily managed, arranged and distributed to the city as a whole. The Functional City was predicated by the “old” city being conceived of as obsolete and an obstacle both to modern technological achievements and a generalized state of contentment in the life of the Welfare-state citizen. Legacies of the Functional City are recognizable today in the form of mono-functional housing estates developed far away from dirty industry and peppered with space for consumption. In Vienna, post-war large scale public housing estates were largely built within the city’s pre-existing urban fabric, yet designed to both appear and feel removed. Trees planted along their perimeters disguise their presence from the outside, and once within, an aestheticized, meandering, spacious landscape between housing blocks resembles something closer to a Mediterranean holiday resort than anything. The vastness of its greenery creates distance both between the estate and the rest of the city and the inhabitants of the estate itself. Views to opposite blocks are obscured, both giving peace and mitigating communication; precluding the potential for friction, but also, for bonding.

Housing originally emerged with the introduction of wage labor. Today, such forms and conditions of labor are rapidly disappearing, yet as a concept, housing has yet to change. Housing is still both thought of and implemented as the serial construction of isolated units, occasionally supplemented with a common room for the community and amenities like playgrounds, saunas or swimming pools. This fainthearted mirroring of the demand for collective spaces that the public no longer is able to provide creates deliberately exclusive islands of community detached from one another within a neighborhood. While units still comply with a bourgeois idea of living, society has become radically re-organized, with an increasing percentage of households inhabited by single occupants. Industry’s only reaction, it seems, is to urgently put forward the question of affordability and ask for creative solutions to dramatically shrink units all the while fitting all of the traditional functions and giving them the sense that they are not in fact so small. While altering pre-existing units or conventional typologies are indeed possible, housing is a passive infrastructure that no longer mirrors reality, not to mention that today’s logic of housing production is detached from the actual needs of urban societies. I argue that in order to conceptualize it in such a way that it mirrors and can accommodate contemporary society’s dynamic in a meaningful way, it is necessary to call housing into question as the space for reproduction vis-à-vis production. What follows is to consider the modes of production and kinds of labor that have become dominant since the end of World War II, identify points of disjunction with forms of life that house its workers, and thus indicate weak points in the system that allow for its potential rearticulation.

Interior of office landscape for the mail order business Buch und Ton (1959/60). Image: Private Archive Office Landscape, Andreas Rumpfhuber

Labor

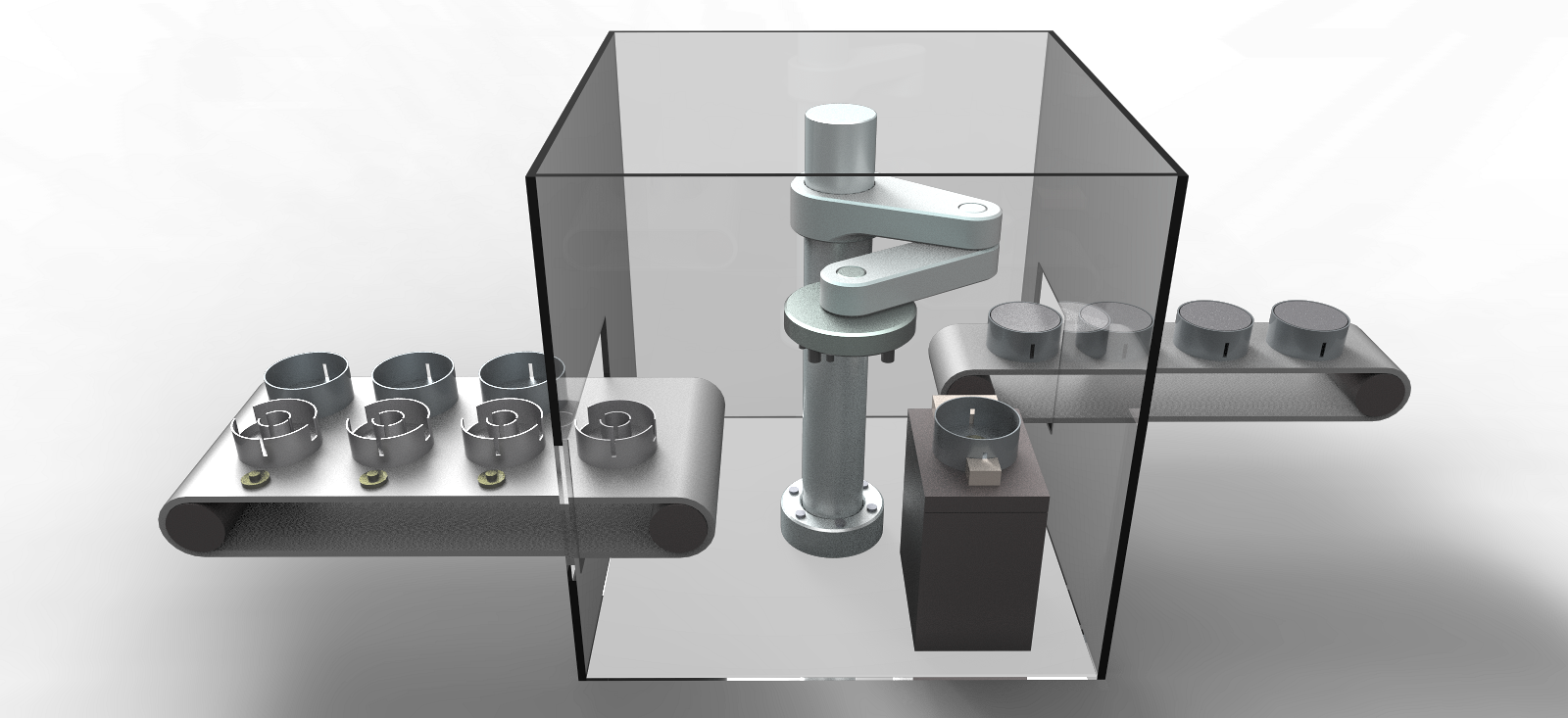

It is not by chance that post-war housing employed prefabrication and automation on an unprecedented scale. As part of a larger restructuring process in Western industrialized countries, a new form of living together was propagated, guided by the pragmatic application of cybernetics and its premise of overcoming despotic and disciplinary forms of governance by means of management and control. The cybernetic model fascinated architects and inspired some of the most radical architectural thought of the period, such as Cedric Price, Joan Littlewood and Gordon Pask’s Fun Palace (1961–1966), Constant Nieuwenhuys’s New Babylon (1956–1974), and Yona Friedman’s Realisable Utopias (1976). While most went largely unrealized, management consultants Wolfgang and Eberhard Schnelle’s implemented cybernetic principles throughout a wide range of built projects with the invention of Bürolandschaft (office-landscape, 1956–1971). Acting as consultants, the Schnelles and their interdisciplinary QUICKBORNER TEAM developed a design and planning method called “organizational cybernetics” (Organisationskybernetik) which, starting in the early 1960s, they used to generate organizational concepts and office space designs for companies looking for administrative innovation.

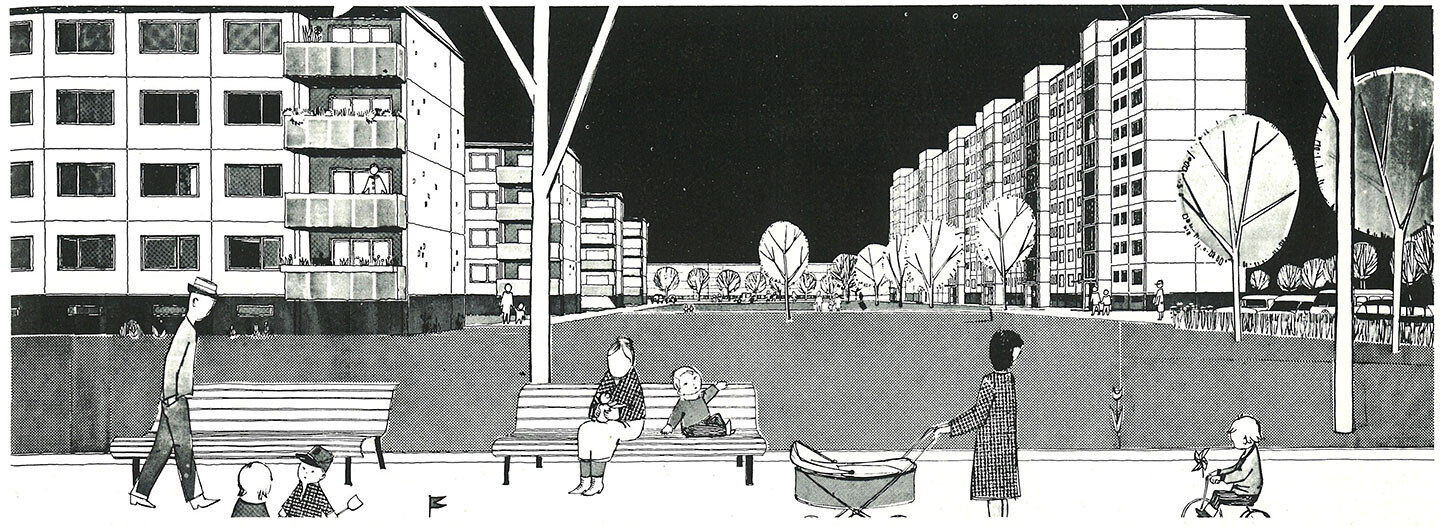

Interior space of the German cooperative GEG’s office (Großeinkaufs-Gesellschaft Deutscher Consumvereine) designed by the Quickborner Team, 1966. Image: Private Archive Office Landscape, Andreas Rumpfhuber.

For the Schnelles, cybernetics presented itself as a new social structure free from hierarchical structure, capable of transforming the alienation of work into the autonomy of individuals. Their pragmatic approach toward the cybernetic organization and rationalization of administrative activity consisted of recording and systematizing every step in the office’s work process. They placed a particular focus on information flows that would allow for as much work as possible to become calculable, and thus automated. Workers responsible for executing on the spot, trivial, repetitive labor could be replaced by information-processing machines, while non-trivial work with a high degree of “informational” uncertainty, which could not be processed by machines at the time, was planned to be worked on by teams of indiviuals.1 While drawing from its predecessor “scientific management,” Organisationskybernetik adopted a more comprehensive approach to the reorganization of labor by taking into account its informal aspects and atmospheric conditions.

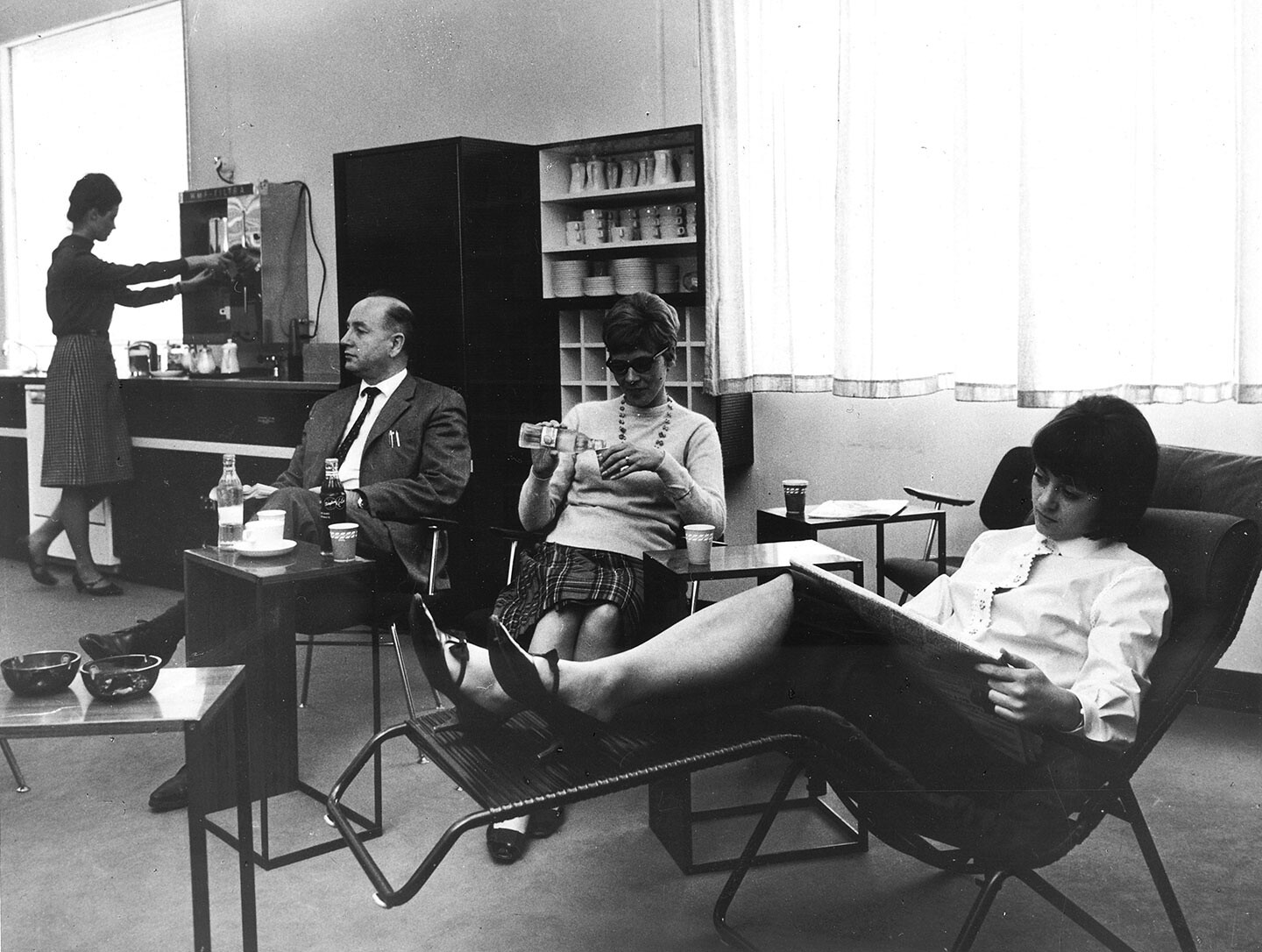

The layout of post-war workplaces were, as portrayed in cinema of the time such as Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1960) or later and to critical effect, Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967), geometrically rigorous with a formally legible hierarchy and, as inherited from early industrial factories, designed for central monitoring and discipline. Office-landscapes were instead designed for a “community” of labor consisting of small groups and teams with no discernible bosses or leaders. With its psychologically inflected color schemes and calculated ordering of workplaces, potted plants, and partitions, office-landscapes were intended to make each individual feel as if they were in a democratically organized space, aware of their social responsibilities, and motivated to work. Fundamental to this was the programmatic incorporation of leisure. A prominent feature of the Schnelles’ office landscapes was the break room, which while appearing distinct from the rest of the office, was understood to be one of the most productive spaces.2 Designed like a modern living room, office-landscape break rooms were furnished with desirable amenities like health loungers, chairs, versatile tables, and counters with sinks and fridges for drinks, food, and ice. Their incorporation of reproduction within the space of production represents an early example of what the Schnelles foresaw to be the programmatic consequence of industrial and administrative automation: the wholesale redundancy of office buildings and workplace architecture in general.

Breakroom within the office landscape of the mail order business Buch und Ton. Image: Private Archive Office Landscape, Andreas Rumpfhuber

Emancipation

The modern dictum of functional differentiation between productive and reproductive spaces (not to mention times) has become completely disintegrated with the contemporary organization of labor. Mario Tronti foresaw this already in 1956 when he coined the term “factory of society.” With what he identified as the dissolution of the formerly clear-cut boundaries of the factory, both the factory spilled out into the city and the city itself and society as a whole became a factory. Consequently, as a set of practices, labor started to entail “skills involving cybernetics and computer control” as well as a series of activities previously considered to be outside the capitalist mode of production more widely like creative work, networking, and reproduction itself.3 With the worker’s classical labor power becoming increasingly obsolete in an automated world, housing and the forms of life of its inhabitants became—and continue to this day—the locus of capitalist exploitation and commodification today.

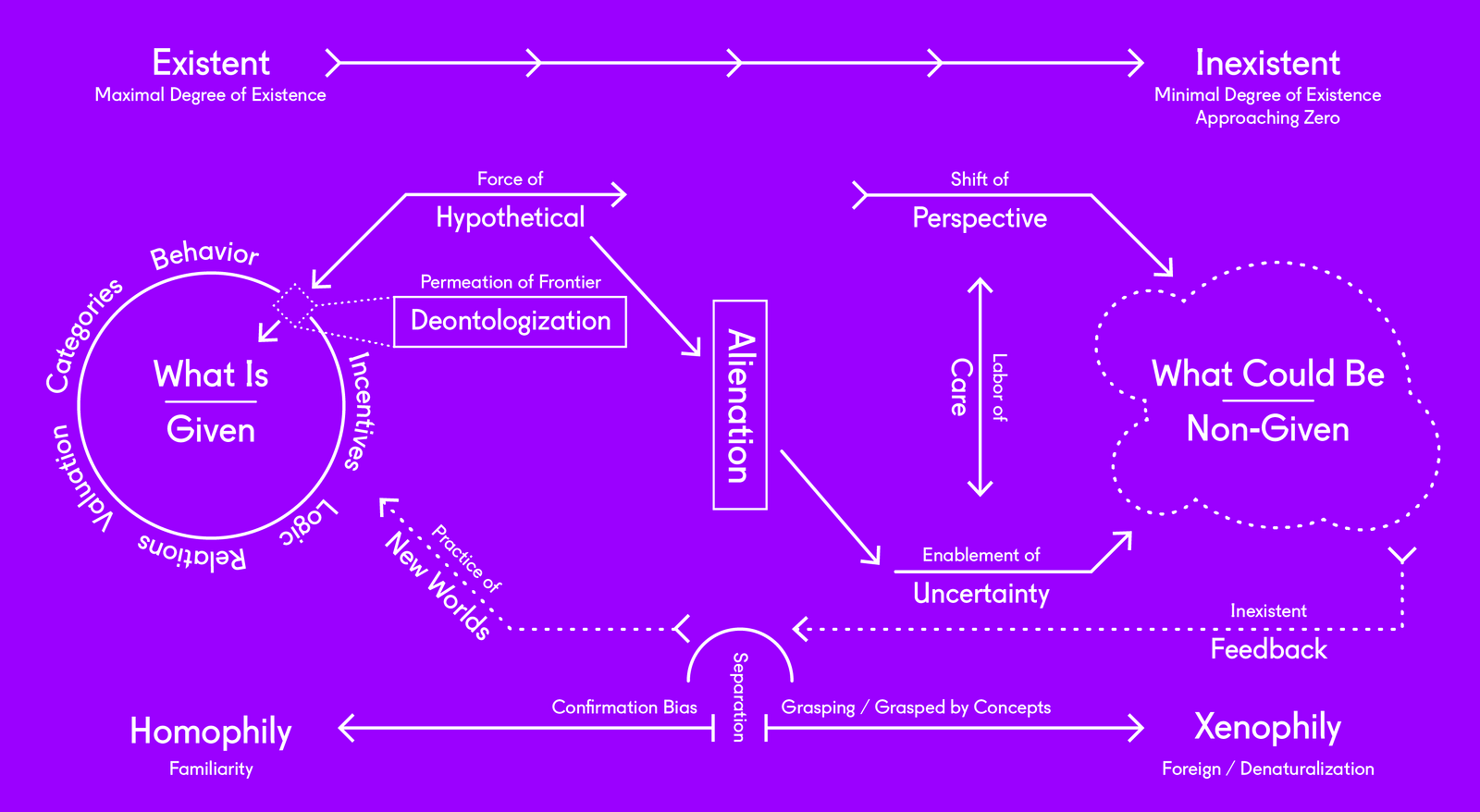

Historically speaking, capitalism has both failed to conceive of reproduction as labor and qualified it as emancipatory. Yet with the increasing penetration of labor into life and the city and its activity becoming the focus of technological innovation, we must recognize housing, domestic space and leisure itself as the capitalist frontier. We can recognize this in two distinct ways. Firstly, the increasing automation of labor and outsourcing of industry has positioned housing and (for the time being) consumption as the only types of space remaining to build and expand the city in reasonable faith. Yet as we can witness with its resurgence after the economic crisis it served as the primary vehicle for, housing is the essential contemporary subject of financial investment. Cities throughout Europe have been experiencing market pressure to rezone former industrial estates for housing; it is literally eating up land that was both formerly and projectively dedicated to material and immaterial production. City administration’s like in Vienna or Brussels are responding by introducing new zoning frameworks that blend housing with more traditional types of spaces for production. The problem is that nobody, and certainly not the developers, know what labor, what production will look like or be in the future European city. The second way we can recognize housing as the contemporary frontier of capitalist exploitation is that we conversely know exactly what counts as productive labor today, but it is recognized neither by its producers nor by those who profit from it as such. Housing itself and its inhabitants are increasingly inundated by technology that, in similar fashion to Organisationskybernetik, gathers and rationalizes as much information as possible. We are the producers of data for the machines of global corporations and their experiments with ever-new, aggressive, and persuasive business models.

It is through this bifocal lens that we should come to view current preoccupations with housing injustice, affordability and wider access to an ongoing process of negotiation over the way we live. Discourse on housing needs to encompass questions of labor. It’s only within this expanded frame that new ideas of meaningful activity and occupation in the future, not to mention alternative economies to the neoliberal, automated capitalism of today, can be thought. We must abandon a given tradition of what housing is and could be in the future; we must reject being content with affordability, dreams of bigger flats, better amenities, or otherwise achieving our commodified dreams. Instead, we should find ways to reinterpret housing as an emancipatory space; as collective infrastructure for both dwelling and working. It is in this sense that we can listen to the provocation, the call of automation; not as a challenge to overcome or escape technology, but rather to affirm it and use it for a future urban collective. Individualistic images and ideas of the good life must be disengaged from in order to make room for the possibility of emancipation for everybody in a world that is labor.

For a detailed analysis and discussion of the restructuring of work processes, see Andreas Rumpfhuber, “Architektur immaterieller Arbeit,” Turia und Kant (2013), pp. 65-79, ➝.

Description of Office Landscape for the Bertelsmann Company in “Buch and Ton” brochure, Quickborner Team Archive, Hamburg.

Maurizzio Lazzarato: “Immaterial Labor,” ➝.

Artificial Labor is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and MAK Wien within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017 and its theme, “Robots. Work. Our Future.”

Category

Artificial Labor is collaborative project between e-flux Architecture and MAK Wien within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017.