It’s a doubtful thing to be in the cultural sway of Venice, especially when you are Montenegrin, like us and our robots.

In their 85th Biennale (that’s the most recent one), the Venetians are perturbed by the world’s robot labor crisis. We Montenegrins, by contrast, are world-renowned as the Earth’s most indolent people. We don’t much fret about the lost jobs and the work, because we’re occupied with our poetry, our folk music, our rugged mountain landscapes and our local habit of gently flipping worry-beads all day.

Still, we must confront the judgmental Venetians and their many cultural anxieties. It’s not that they harass us every day, but every two years, they do get frenetic.

‟You people,” they informed me just now, because of my regional art-world connections, “You Montenegrin people are so lazy that you can’t even name your own country. Venice had to do that.” (“Monte Negro” simply means “Crna Gora,” but Italians can’t pronounce our real name.) “Also, Venice built all your best seaside resort towns.”

The modern Venetians are always carrying on about cities, because, in these days of sharply rising sea-levels, all seaside cities are becoming Venice. Yes, it’s canals for streets in New York, London, Tokyo; for all of them.

Every seaside city on Earth must follow the cultural lead of Venice. That’s simply how it is and must be. That is also why the Beachcomber Robot of Novi Kotor is the hardest-working robot in all of Montenegro.

He is certainly an examplar of robot labor, yet also a critically important artwork.

The Beachcomber is tireless, colorful, unique, and a major local tourist attraction. Since I am the host and proprietor of the “Pirate Robot Travel Lounge” of Novi Kotor, it’s up to me to explain the robot phenomenon to you.

American tourists—(we get more than a few of those)—are especially demanding. “Who built that crazy robot? Who owns the software? What’s the business model?” And so on. But such nervous anxiety over petty matters, that’s not how culture develops in this region.

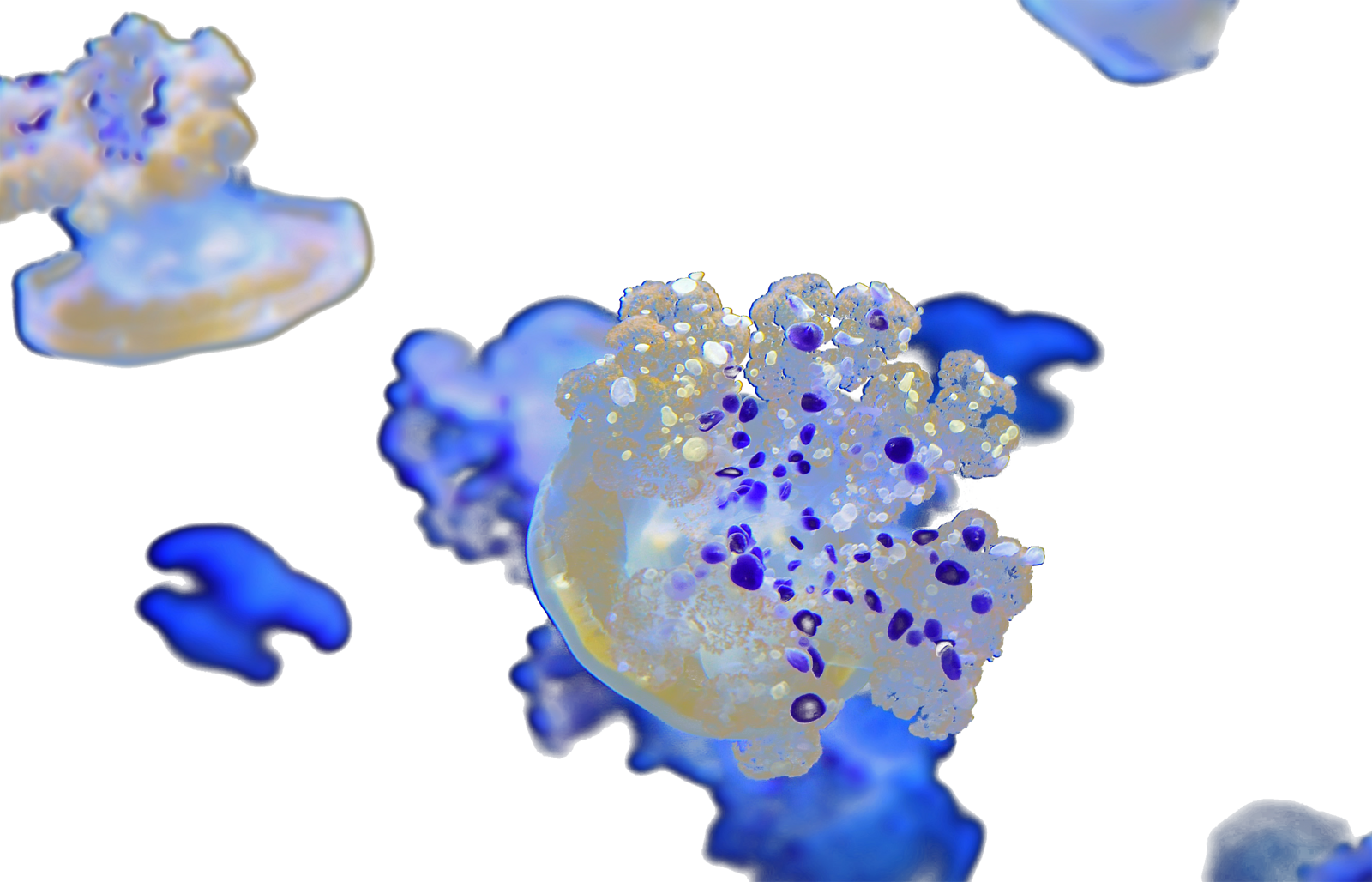

First, the Beachcomber is not a rigid steel machine. He’s soft. He’s a big wet balloon with some telescoping canes inside, and about a thousand cheap little shiny sensors on his plastic skin, much like the sequins on a Carnivale costume. He’s large and colorful and yet mostly empty space, like a windsurfer’s parafoil or a beach-camper’s pop-up tent.

He’s powered entirely by wind energy, for we get plenty of wind on the mountainous coastline of Montenegro. So, he rambles wetly around the shore, as soft and sticky as a sea-cucumber. He picks up the floating debris of our submerging world.

The Beachcomber peers and sniffs with his sensors for any washed-up debris that seems to be out of place on his native beach. Whenever he sees it, he engulfs it, sea anemone style. Eventually, he’s too heavy with his waterlogged booty to move much. Then he squelches over to the Novi Kotor’s Pirate Robot Travel Lounge, amoeba style, and disgorges his treasure into the parking garage.

Teenagers are usually the first to go through the stuff, since my son and his friends have plenty of time on their hands. Given that Rimini, Ancona, Pescari and Bari are all submerging fast, there’s plenty of European Union debris on the Adriatic tides. Typically, Italian designer products will surf in, due to their floating plastics.

The Beachcomber himself is mostly constructed from plastics. So, conceptually (if you follow me) what we have here is a petroleum-based plastic robot who eats plastic petroleum products blown in from the plastic-drenched sea by the wet Greenhouse storm-surges caused by burnt petroleum. He’s crisis, solution, debris and creation all at once.

If you’ve got one particle of poetry in your soul—if you’ve got a human soul at all, really—you’d have to see why a robot of this profound and relevant character would come into existence here, and why he would become such a mascot for us.

There’s only one of him in the world. He’s not a mass-produced robot like some American self-driving car. The Beachcomber is a native work of Balkan device-art.

Now let me explain, for the sake of the Venetian biennial art crowd, why this big, beloved, rubber-balloon guy radiates so much raw Walter Benjamin Aura.

You see—and I know that art-theory is complex, but bear with me, this is Montenegro, where we never have to hurry much—our Beachcomber is a robot that’s more “grown” than manufactured. He labors at cleaning his beach, but he doesn’t “know,” and can’t ever know, what beach trash actually is. The Beachcomber has no intelligence and no hard-and-fast software rules. Instead, through machine experience, the Beachcomber “deep learns” about the litter, the matter-out-of-place, on his own native beach. He deduces patterns with statistics from his sensors, and is constantly re-educating himself.

That’s what gives him his unique quirkiness. He was never one of those man-shaped Karel Capek “robots” from Czech theater in the 1920s. He’s a soft, ductile “neural net,” a robot like an aquatic filter-feeder organism.

The Beachcomber needs no venture funding and is too simple to need much repair. So as a laborer, he’s almost ideal; it’s common to hear him out there on the wet strand, unpaid yet persistent, gently munching his beach trash in the darkness of three in the morning.

Whenever there’s enough wind to get him moving, and enough waves to bring him his fodder, then out he goes, to follow his robotic passion.

Once he’s achieved a hugood battery charge, he’ll be out on his working rounds, usually followed by shouting children, and plucking up trash in his mystic yet decisive way, just like a deep-learning robot will pluck the captured stones off a Go-board.

Our Beachcomber is a thousand times better at combing a beach than any human laborer can ever be. You could send out a hundred German volunteers to clean our beach (we wouldn’t perform that labor ourselves, for this being Montenegro), but no matter how selfless and green and guilt-stricken they are, the Beachcomber robot will surely beat them.

If human workers bring in a hundred sacks of filth and swear they’ve fully scrubbed that beach, then the Beachcomber will go to that very same beach and bring in another two-hundredweight. I have personally seen that happen. It uses porous mesh in its membranes and sucks up tiny plastic shreds that are too small for a human eye to see.

There’s simply no possible man-machine competition here. The Beachcomber is robotically superb. You could no more beat him than a human can beat a whale at sucking in krill with baleen teeth. As I said earlier, that’s how it is and it must be.

So, if you’re American, at this point, you might characteristically think: Wait! If this robot works so well, why aren’t there a million of them? Why don’t I have one myself? I’m a rugged individualist mass consumer, I have some revenue! What’s the robot’s price-point?

Well, that’s where the “device art” issue reigns supreme. Artists built the original Beachcomber here. Our “Pirate Robot Travel Lounge” is something of a bohemian atelier.

Years ago, before the seas rose, the compound was a five-star seaside Montenegrin hotel, mostly enjoyed by Russian oil and gas moguls.

However, the fossil-fuel business put half the fine hotel underwater. During the ensuing global commotion, the Russians had one of those extremist political episodes they’re well-known for. All the neo-Czarist neo-aristocrats had to flee their beloved pipelines and scatter to the winds.

So, our soggy hotel was reduced to sheltering mere artists rather than offshore fine-art collectors. However, we didn’t give up hope; we Montenegrins are an enduring people; we just sold off all the gold-plated faucets and became a louche, sleazy artists’ dive.

Our new clientele were shaggy, windblown creatives with bad passports and worse drug habits, along with some disaffected European intellectuals who somehow didn’t mind our electrical blackouts and Arte Povera lifestyle.

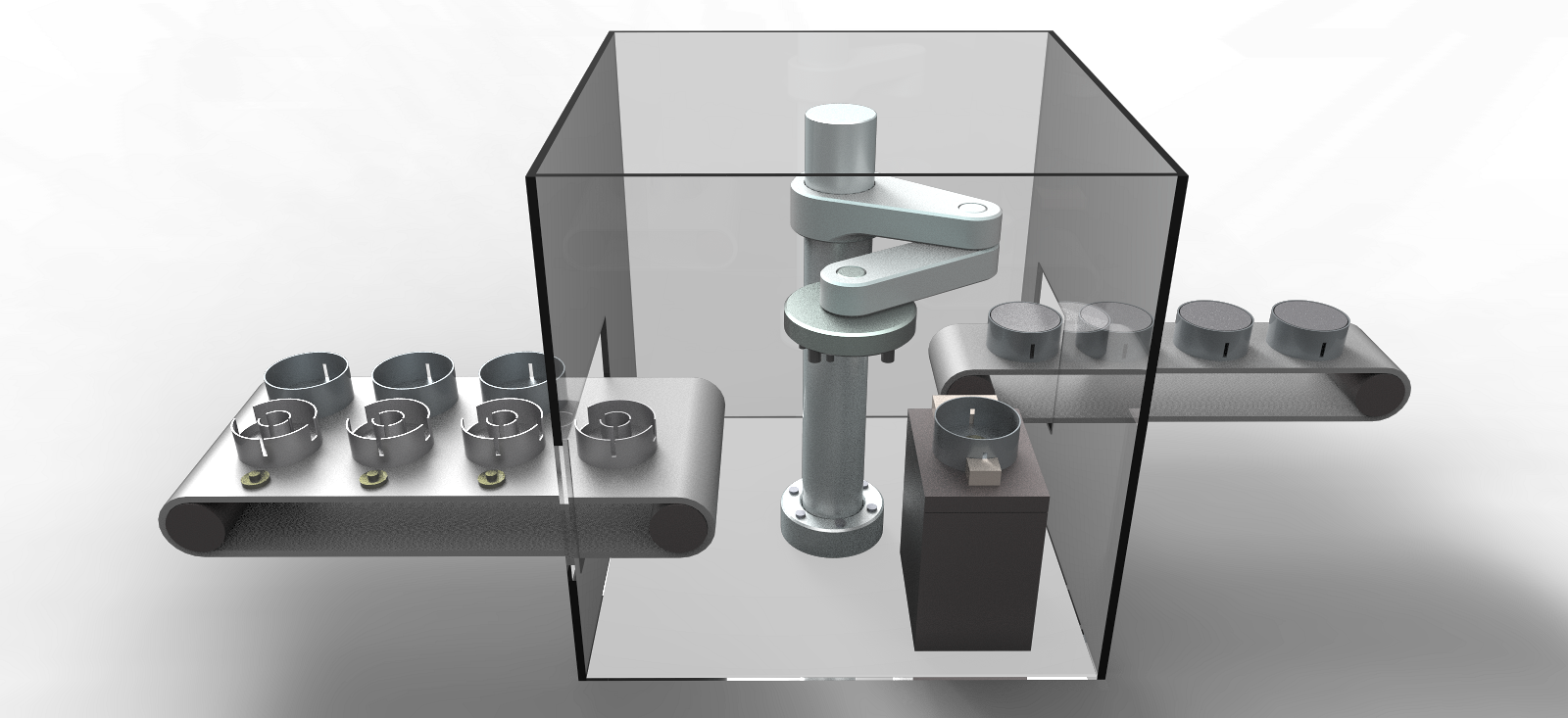

Some of our artist guests built the Beachcomber from semi-licit electronic scrap. They ironed out the fatal bugs from its open-source software. Then they simply released it. Let it loose in the wild, with its parameters set-up so that the robot could generate more of itself from the landscape.

At its first alpha-release, the Beachcomber was small and buzzy, like a domestic robot vacuum cleaner. But every so often, it would smelt and 3DPrint a few new plastic members for itself, using the debris of the beach. It also managed to knit and wrap its many membranes and sails.

In its youth, it was humble. It looked like a plastic compost heap, a salty little dervish of sentient trash. Sometimes violent storms would wash it out to sea, but with a robot’s GPS instincts, it somehow wallowed back to its place of origin.

Then he grew. He got bigger, grander. Eventually he maxed out at about the size of two-story yacht-repair facility. But we’ve got plenty of other yacht barns around, and by that time, we’d become truly fond of him.

Sure, he was just a robot, but he had character. He was a monument to our spirit of place. He was our site-specific mobile sculpture, like from Burning Man, but without those incessant drumbeats and the hallucinogens.

There were moments, like during the Green Flash of dusk on the beach, when he was beautiful, like an element in a Chinese landscape painting. Except that, unlike a painting, no Chinese mogul would arrive on a private jet to buy him and take him away.

Obviously, as a site-specific artwork, the Beachcomber just couldn’t work without the Montenegrin environment that had created him. He was too firmly integrated with the genius loci to be of any use in an art gallery. Also, being made of beach trash, he was rather smelly.

Some stubborn people still might argue: “But why couldn’t a technical innovation like that be rationalized and commoditized? It’s simply a robot, it exists for garbage labor! Do a mass market knock-off! Put one on every dirty beach in the world!”

Yes, certain people said all that, and even tried that. Half the American state of Florida is under water, it has needs. However: a commercial robot that is engineered and optimized for the sake of shareholder return won’t really clean the beach for you. No. Its heart isn’t in that job.

A robot of that kind will learn to clean just enough of the beach to increase the market demand for more robots. That robot will “work,” but only like those on-demand robot taxi services that diabolically increase their prices in the very moment that you most need at taxi. Very likely, I don’t have to explain that problem to people who take limos to art events.

Whenever a robot is at work for its own robot-ness, it can achieve a strange, awkward beauty, like one of Bruno Munari’s Useless Machines. It does its machine thing and you do your human thing, and you glance at it every once in a while, and its unearthly Bruno-Munari-ness is rather superb.

But when a robot is into market labor in order to maximize revenue flows, oh my goodness, will it ever skin you. It doesn’t just shear a flock of human customers like some human big-businessman will do; no, it’ll chop right through the bones. It will generate cash with opaque methods that no human will ever comprehend.

So now you know about the Beachcomber of Novi Kotor. I have to be careful about promoting its legend, because otherwise we’d get Venetian-scale hordes of tourists down here. There would nothing left of my sleepy art colony but pizza carts and Punchinello masks.

Sometimes people darkly whisper: since it cleans beaches so well, has the robot ever found sunken treasure? Did the robot ever find a chest of gold under the beach, a pirate horde from all those famous Balkan brigands and corsairs?

Well, yes. Of course I always tell them yes.

Artificial Labor is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and MAK Wien within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017 and its theme, “Robots. Work. Our Future.”

Category

Subject

Artificial Labor is collaborative project between e-flux Architecture and MAK Wien within the context of the VIENNA BIENNALE 2017.