Mud is another element. One comes to love it, to be like a wading bird, happy only at the edges of the world where land and water meet, where there is no shade and nowhere for fear to hide.

—J. A. Baker1

1.

That Robert Rauschenberg’s Mud Muse (1971) is an artwork for the twenty-first century lies in its acceptance of the apocalypse with a shrug and a burp: a disclaimer of any techno-utopia and of our abiding faith in new technology as a panacea, a redeemer.

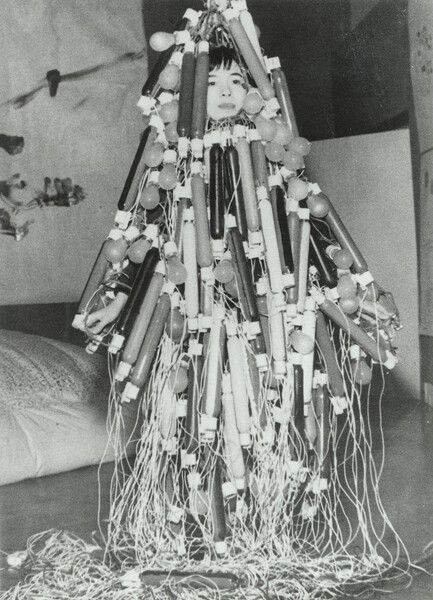

Performing a random, boiling encounter between sound and artificial goo, Mud Muse imbues a minimalist framework with dubious use value as an enframing of sludge and flatulence. In a large vat, sound in the form of compressed air passes through valves to make little ploppy geysers erupt in thousands of pounds of so-called driller’s mud—a mix of glycerine and finely ground volcanic ash used in industry to cool oil drills and fill vacuums in bedrock. A hi-fi system that is a visible part of the installation plays pre-recorded blurbs in various frequencies through the mud, setting off new unsounds that become part of the work’s recursive, mud-kicking action by feeding back into the sound system.2 Mud Muse deflates expectations to pushbutton abstraction and numerical efficiency, and instead turns data into so many stains in the real, throwing up opaque issues in the process. This stupid, disrespectful work allows for the question of the relationship between art and technology to be continuously reopened: After all, who will ever know what is the “mud muse” that turns our meeting with technology into a queer mess? Rauschenberg’s strange installation refuses to sell an agenda or a bottom line, let alone any harmonic resolution between the human subject and the world that it created.

Technology seems to be an integrated, realized condition today. Certainly not because contemporary civilization is the first to live technologically, but specifically in the sense that to be a citizen, consumer, worker, and any other subject in today’s globalized West is to be a user of “networked digital information technology.”3 This is the dominant mode through which we experience the everyday, organize perception, gauge reality, and engage with the future. Moreover, the political economy of life mining—the capitalization of living matter and all that lives—has technological mediation as its precondition.4 Perhaps not coincidentally, life’s integration with technology takes place simultaneously with how Western culture finds itself at the limits of the certainties that brought us to the present; certainties that (as Rosi Braidotti sums up) were pinned on humanist Man’s power to assign difference on a hierarchical scale through a dialectics of otherness.5 This regime faces dismantling, whether by numerous showdowns with its binary epistemology, or observably in events where quantities that were previously kept apart in terms of “culture” and “nature,” “antropos” and “cosmos,” now resist clean separation.6

Such events confront our means of analysis and comprehension because they embroil and compromise our concepts. For instance, even as it seems obvious to use about our present relation with technology, the term “integration” remains an ideological one whose suggestion of seamlessness disarticulates the power arrangements that precede it and the processes that change it. Pervasive ambiguity spills from binaries that are irreparably broken; when exclusionary politics try to uphold them, anger and violence are inevitable results. But how to characterize the co-existence of differences ungoverned by the categorical hygiene of binary sorting, if “integration” is mendacious? For good reasons, in recent years the notion of “entanglement” has become a staple of descriptive and critical efforts, but the question is if the term literally goes deep enough; maybe we need to think of intra-nglement to disabuse us of the idea of constituent parts that exist originally on their own previous to the tangle.

The most developed idea of this dizzying condition comes via the concept of symbiosis, understood as a radical state of living together or together-being. It usually describes a parasitic or cooperative co-development of bodies and systems, but it can also be used to encompass the constitutive mesh of discourses, taxonomies and systems in continuous and scale-defiant mixes of agencies, intelligences, and ontologies. A growing-across and a synthesizing-within, pushing origins and destinations in mutual displacement of difference in more or less manageable, more or less livable proximity. As much as it is co-existence and co-determination, symbiosis is life that is always-already mediated, life lived in contradiction and struggle.

Mud is a fitting image for such together-mess, more precisely cybernetic mud as a dialectical image of symbiosis when it becomes a mash-up of binaries, good and proper. Rauschenberg’s Mud Muse speaks to a contemporary symbiotic imagination in a number of ways, but most clearly in that it is a result of the 1960s dream of an art-technology alliance that, in this case, made irreducibly dissimilar referents and material realities co-exist: synthetic mud and cybernetic feedback. The mid-twentieth century art-technology juxtaposition remains anachronistically relevant, as its mutability encompasses a longer timespan than that defined by the rise of the internet and the present hegemony of digital mediation, providing the opportunity to assess historical change and to consider other directions that will shape the future.

2.

Mud Muse came out of one of the big US curatorial initiatives of the 1960s. Between 1967 and 1971, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s Art and Technology Program (A&T) paired artists with private corporations to produce new artworks. Curator Maurice Tuchman cited a “gathering esthetic urge” among artists “to gain access to modern industry” for the program’s art and business collaborations. He compared this with “the programs of the Italian Futurists, Russian Constructivists, and many of the German Bauhaus artists”—a perspective that no doubt sanitized the avant-garde’s political history while conflating technical know-how with avant-garde expectations.7

For the production of his new commission, Rauschenberg collaborated with personnel of the industrial conglomerate Teledyne Inc., an aerospace-oriented industry that developed hydraulics, optics, and electrical products for commercial and military clients. It was also Teledyne that in 1973 gave the work to Moderna Museet in Stockholm, where it arrived in a group of other North American acquisitions and donations that was critically received by some local artists and activists with period accusations of “technocratic emptiness” and cultural imperialism.8 To the Stockholm protesters, Moderna Museet director Pontus Hultén failed to critically engage with socioeconomic realities, and they took him to task for not disclosing sources of donations, as well as for declining to respond to whether Moderna symbolically condoned the US military-industrial complex. Rauschenberg laconically offered that “it is essential that art is considered in industry”; a consideration that at the time was overwhelmingly gendered and racialized, as evidenced by the almost exclusively all-white-male A&T Program’s list of artists.9

Mud Muse is as dirty as you want it to be. Rauschenberg—not one to shy away from a good visual pun on unstraight forms of sex—gleefully conceded the work’s lack of morality and content: “There is no lesson,” no “interesting idea.” Instead he understood it to simply operate on “a basic, sensual level,” as evoked by animated mud that is “light brown in color and extremely soft to the touch.”10 Mud Muse’s profane mix of “pure waste” and “sophisticated technology” also mediates scatological and eschatological: to put it with activist anger, technology can be recruited for shitty purposes, too, such as the optical systems developed by Teledyne for the US Air Force and employed in the Vietnam War.

At the same time as its social history and institutional provenance mumble along with the work’s unsounds, Mud Muse insists that we consider what is down there. The work makes for a media archaeology into a bottomless concept of technology where the newness of the new is summarily dissolved in the longue durée of the primordial soup. Theory attuned to disorderly entwinements is now catching up to Rauschenberg’s provocation, such as Shannon Mattern’s recent history of five thousand years of urban media, in which she dives into civilizations’ material substrate of mud and its analogs clay, stone, brick, and concrete that “have supplied the foundations for our human settlements and forms of symbolic communication,” and thus bind together “our media, urban, architectural, and environmental histories.”11 A dramatization of the uncertainty of where (human) life begins and technology ends, Mud Muse shows mud as alien and archaic, too: it is a material found at the beginning and at the end of times, but also in places where humanity loses its grip on history.

The twentieth century understood technological progress as a means to harness the changeability of human capacities, an ideology Mud Muse feeds to itself in a pointless feedback loop. Basking in the aftereffects of technology as a human-made evacuation of human agency, we continue to enact contradictory expectations to technology, like how its capacity for revolutionizing production and social process has placed it at the center of human history, while at the same time it is considered to be in excess of that history. Similarly, on the one hand it makes us self-present as modern, and on the other it allows us to surpass ourselves as such by pulling us into the future. And new tech demands that we adapt, we are told: we owe it to carry out the required changes in ourselves, as if it were a highly dynamic sort of ontological debt. Technology is also understood to augment certain cultures and make them superior to notionally un-progressed cultures, in a colonial annulment of the possibility of a shared co-existence. And we have made a profound mess of this planet by imagining extraction-dependent technologies as exemplary for progress, as if its tacit premise were exploitation and destruction of ecosystems. But luckily, technology can clean up after technology and fix all that, so long as it is immaculately conceived with ideological leverage to pull ourselves out of the miasma by our collective ponytail in a perfect transcendental loop.

Robert Rauschenberg, Mud Muse, 1968–1971. Installation view from EXPLOSION! Painting as Action, Moderna Museet, 2012.

Photo: Moderna Museet/Åsa Lundén.

3.

Not only its nihilism makes Mud Muse strangely contemporary, but also how it is couched in cybernetic speculation. The collapses that Rauschenberg’s work effectuates bring it close to how theoretical cybernetics—as outlined by Norbert Wiener, Heinz von Foerster, and Stafford Beer, among others—deliberately hooked up and cancelled binaries of electronic circuit and animal nervous system, idea and matter, and even magic and science. No ecology is ever alone, and intelligence exists within intelligence. In this sense cybernetics described a radical, prescient form of bio-tech. In 1956, when the twentieth century was recovering after World War II and not long after the fledgling science had been baptised, Ross Ashby defined cybernetics with indifference to existing certainties. He wrote: “Cybernetics takes as its subject-matter the domain of all possible machines, and is only secondarily interested if informed that some of them have not yet been made, either by Man or Nature.”12 Ashby took the pre-modern notion of nature as a giant clockwork device and allowed the boundless notion of “all possible machines” to usurp the function that God once had as the prime mover that made it tick. By anchoring possibility in a future that does not result from human agency alone, he re-arranged scientific reliance on what can be positively known.

Such a time-space continuum, in which machines are abstract and fictional as much as they are real and reproductive, is inimical to the status quo, or based in what Andrew Pickering calls an “ontology of unknowability.”13 In a radical way, cybernetics gives notice that another future is not only possible, but that tomorrow must be different. As conceptualized by Ashby, the cyberneticist’s mid-twentieth-century dream of technology is rife with premonitions of the current dismantling the modern mind’s binary constitution. Its concepts and tools and a range of its conclusions were of their day, but cybernetics went a long way to undoing the conceptual watersheds between nature and culture, information and matter, in implicit opposition to the later manifestation of managerial cybernetics and its Cartesian “teleology of disembodiment” (as N. Katherine Hayles puts it).14 In theoretical cybernetics as a genealogy that points elsewhere than to our contemporary technosphere, today more than ever we can recognize the artificial brain not as an abstract thinker but as a performing organ within living systems.15

This mindset is a reference point in recent history for when binaries break down. The eco-epistemological implications of Beth Dempster’s term “sympoiesis” comes across as self-evident today, as it echoes cybernetics and hooks up with biology in that elastic way of systems analysis. Coined in an article from 2000, she proposes that the autopoietic and the sympoietic present a useful heuristic as caricatures at ends of a conceptual continuum. In this way, the essential differences between the two types of poietic systems “relate to the presence and lack of self-defined boundaries and their different degrees of organizational closure… autopoietic systems have self-defined boundaries, sympoietic [collectively-produced] systems do not… autopoietic systems are organizationally closed, sympoietic systems are organizationally ajar… sympoietic systems are … evolutionary, distributively controlled, unpredictable and adaptive.”16 Considered as a system of action, Mud Muse can be seen as an autopoietic work because it seems to produce nothing other than itself to its own unappetizing tune. However, seen as a semiotic system, it may be called sympoietic insofar as it is organizationally ajar and—both deliberately and inadvertently—opens up to other events and épistémes than art, and to social history at large.

While autopoiesis has been applied as an organism metaphor by thinkers such as Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, sympoiesis places emphasis on the systemic fusing or being-together between and across entities that share company, or have grafted themselves onto each other or otherwise allied themselves.17 Sympoiesis is making- and being-with; Haraway’s fundamental form of “making kin.”18 “Symbiotic interaction is the stuff of life on a crowded planet,” Lynn Margulis concluded in her research of how differentiated human cells arose through the symbiosis of lifeforms that totally merged into a single collaborative cell.19 And for biologist Scott Gilbert, symbiosis appears to be the rule rather than the exception, which implies that nature itself may be selecting relationships rather than individuals or genomes; accordingly, when the unit of evolution changes in this way, “almost all development may be co-development.”20 Besides being a mutually contingent yet non-integrated spatial relation, then, symbiosis also describes one of constitutively uneven temporalities beyond affiliation.

Caroline Jones recently coined the term “symbiontics” to propose an overarching analytic that gives “a direction toward which to aim our cultural evolution, if our [human] particular forms of consciousness are to survive.”21 To Jones, Margulis’s hypothesis about the symbiotic origins of multicellular life challenged evolutionary morphologies in favor of horizontal transfers of genes from hosts to symbionts, from macrobes to microbes, and vice versa, making “hash of Darwin’s survival of the fittest.” What we see in place of the reductive individualism of a single gene or cell is instead the “survival of the most intradependent,” ultimately the environmental metagenome, the whole network subject to “evolutionary pressure.”22 The lesson of biology and discourses derived thereof is that organisms are most likely to do best when mutualist in their environments, forming ongoing and flexible symbiotic relationships.

Yet in order to understand and promote symbiontics as a process of mutually constitutive, heterogeneous connectedness that cannot necessarily be picked up on the narrow band of human perception, new means and ways to express, exist, and go on within this experience must be actively produced. Importantly, apart from human relationships with all manner of life forms, a critical analytic of symbiontics would include our decidedly non-mutualist, life-threatening entanglement with late capitalism’s mechanisms of capture and all its ramifications—not least its life-mining technologies. If we are to aim our “cultural evolution” toward symbiontic existence—as it passes through human-historic relations of production as well as their nonhuman preconditions and aftereffects—the political economy of this coexistence must be confronted. How can symbiogenesis be enlisted towards change as the human-nonhuman mix that will turn the tide against the naturalism of capital—as, for instance, expressed in ideologies of social Darwinism that Maturana and Varela argued against already half a century ago?

This points towards a fundamental irritability that must be acknowledged when we realize that while difference is constitutive, it has lost its humanist, metaphysical mooring. To Norbert Wiener irritability represented a fundamental life phenomenon: a lower limit of stimulation, friction, and excitement, or other ways in which tolerance is pushed and general equilibrium disturbed. With this, the positive and positivist connotations of symbiosis—such as remainders of homeostasis and holism that lurk on the human-symbolic-cultural side of the notion—can be shed. As proposed by psychoanalysis (another twentieth-century ecology of the mind) the price to pay for acculturation is Unbehagen, discomfort or discontent. Symbiosis also comes at the necessary cost of self. As much as a blessing, every type of kinship can be vexing, even if the relation isn’t hierarchical or predatory. Neither on the human side of things, nor very likely from the molecular perspective of irritated materials, in the commonality of the many-sided struggle to persevere in the mess of life is there a beyond or a sublation. This inescapable volatility and opacity could be an avenue for the inquiry into sympoiesis and the troublesome ongoingness of life and living matter, and the frames of reference we need to find for it.

Art is unique among semiotic and symbolic orders inasmuch as it tolerates chaos. When art’s relation with technology refuses resolution, the latter’s production of time and space is shown to always give us something more than what we bargained and thought we had accounted for: bubbles and spills and other imponderable material excesses that can be folded, stretched, and reconstructed. Mud Muse’s totally irritating pulling together of signal and noise, debased culture and simulated nature, primeval soup and apocalyptic wasteland—not to mention its having been brought forth by a military contractor—is a feat of perverse, multi-systemic sympoiesis beyond authorial control. In the interpenetration of fundamentally different realms of being, technology becomes impossible to capture as a thing in itself; that is, its perceived contextlessness that prevents us from raising the problems that neither technical solutions nor recourse to natural tropes can adequately address.

J. A. Baker: The Peregrine (New York: Harper & Row, 1967). I am grateful to Nick Axel for the “How to Use a Mud Muse” part of this essay’s title. Parts and earlier versions of this essay have previously been presented at the Zooetics+ Symposium, MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology, April 28, 2018; at Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas’s Swamp School, at the Lithuanian Pavilion of the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennial on June 26, 2018; and on November 2-4 at the Museum in Transition, the 2018 CIMAM conference at Moderna Museet and Bonniers Konsthall.

“Unsounds” is Steve Goodman’s term for sonic matter that is “suspect, unsavoury, or ignores rules and norms.” See Steve Goodman, Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010), 9.

Adam Greenfield, Radical Technologies. The Design of Everyday Life (London: Verso, 2018), 6.

Rosi Braidotti credits Jose van Dijck for the term “life mining.” See Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 62.

Ibid., 68.

The mixing up of nature and culture are of course stakes in current discussions about the terms and realities of the—anthropocene, capitalocene—climate crisis. Edoardo Viveiros de Castro and Déborah Danowski make the point about our inability to distinguish between anthropological and cosmological orders the way one did in the modern era in their Ha mundo por vir? Ensaio sobre os medos e os fins (Florianópolis: Editora Cultura e Barbárie, 2014).

Maurice Tuchman, ed., A Report on the Art & Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967-1971 (Los Angeles: County Museum of Art, 1971), 9. Tuchman curated the Program in collaboration with Jane Livingston. Tuchman’s rhetoric echoes that of the E.A.T., of which Rauschenberg was a founding partner; an initiative that was seen by its founders as representing an “organic social revolution.” From Matthew Wisnioski, Engineers for Change: Competing Visions of Technology in 1960s America (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2012), 143.

In the US, the critical reception of the A&T “corporate art” project was in many cases no less hostile. See Kim West, The Exhibitionary Complex. Exhibition, Apparatus, and Media from Kulturhuset to the Centre Pompidou, 1963-1977, PhD dissertation, Södertörn University, 2017, 240. For a brief summary of his own and Max Kozloff’s Artforum International reviews of A&T, see Jack Burnham, “Art and Technology: The Panacea That Failed,” originally published in Kathleen Woodward ed., The Myths of Information: Technology and Post-Industrial Culture (Madison: Coda Press, 1980), ➝.

Tuchman, 285. All of the artists of the Art and Technology Program except two—Channa Davis and Aleksandra Kasuba—were male, and the lineup was a mix of European and American artists in a disparate mix of stellar names, including Max Bill, Öyvind Fahlström, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Jean Dubuffet, Michael Asher, and Andy Warhol.

Tuchman, 285, 286, 282.

Shannon Mattern: Code and Clay, Data and Dirt. Five Thousand Years of Urban Media (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), xxix, 88, 113. To Rauschenberg, Mud Muse built associatively on naturally occurring sludge fountains at Yellowstone National Park: so-called “paint pots” in which rising gases and thermal heat drive strongly colored mud out of the earth. Within his own production, he relates Mud Muse to the ¨earth paintings¨ from the 1950s. But the aesthetic and perceptual transvaluations performed by the work go beyond media specificity. We can allow Mud Muse to depart for a post-medial and interdisciplinary hermeneutic framework via Leo Steinberg’s concept of the flatbed picture plane, with which he proposed to characterize the picture plane of 1960s painting. Steinberg borrowed the term from the flatbed printing press that again evokes flatbed scanners and embedded technologies at our end of history.

Ross Ashby, An Introduction to Cybernetics (London: Chapman and Hall, 1957), 2.

See Andrew Pickering, “Cybernetics in Action” and my own “All Systems Flow. Fiction and play on the cybernetic plane of history,” in The Two-Sided Lake (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016). See also Andrew Pickering, The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future (Chicago and London:Chicago University Press, 2010).

N. Katherine Hayles: How We Became Pothuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics (Chicago and London: Chicago University Press, 1999), 26.

Today, cybernetics is a defunct branch of research. It is no longer to be found in the US government’s lexicon of research topics that can receive federal funding, and the American Society for Cybernetics has only a few dozen members. This might seem strange given the genealogical relation between Cybernetics and the development of personal computing and the Internet. The more that reality is mediated by the internet, on the other hand, the clearer it becomes that there are aspects of cybernetics that have no direct bearing on today’s near-inescapable digitality. Hence it is a partial truth that cybernetics is pre-internet; from another perspective than the corporate sublime of digital networks, the heirs to Cybernetics’ speculative ethos are more playful and irritable phenomena in art and computational cultures that are typically at odds with existing cartographies of power.

Beth Dempster: “Sympoietic and Autopoietic Systems: A New Distinction for Self-organizing Systems,” paper presented at the 44th Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Systems Sciences, ➝.

Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living (Dordrecht: Springer, 1973).

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016), 58–98.

Lynn Margulis, Symbiotic Planet. A New Look at Evolution (Amherst: Basic Books, 1998), 21.

Scott Gilbert lecture at the Zooetics+ Symposium, MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology, April 28, 2018.

Caroline Jones: “Sensing Symbiontics, or, Being with Archaeo-Bacteria,” unpublished manuscript for the Concordia University Hexagram lecture, May 3, 2018, 9.

Ibid., 10.

Are Friends Electric? is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Moderna Museet within the context of its exhibition Mud Muses: A Rant about Technology.