Are Friends Electric? is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Moderna Museet within the context of its exhibition Mud Muses: A Rant about Technology, featuring contributions by Lars Bang Larsen, Ian Cheng and Ben Vickers, Adam Greenfield, Miranda Hall, Florian Idenburg and LeeAnn Seun, Laura Kurgan, Dare Brawley, Brian House, Jia Zhang, and Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Anna Puigjaner and Guillermo López, R. H. Quaytman, Sven-Olov Wallenstein and Koo Jeong A, Kim West, Liam Young, and more.

“We will become vastly smarter as we merge with our technology,” says Ray Kurzweil, Google’s Director of Engineering.1 “Let there be a digital future, but let it be a human future first,” counters Shoshana Zuboff, author of Surveillance Capitalism, an analysis of “the scandalous abuse of digital capabilities” in our information civilization.2 Today’s philosophical assessments of the role of technology are torn between such extremes. The same is true of the worlds of art and architecture, inhabited as they are by techno-optimism as well as extreme skepticism. At a moment when we can no longer imagine a world without technology, it is vital to ask how we—the human inhabitants of this planet—imagine the world and its technologies?

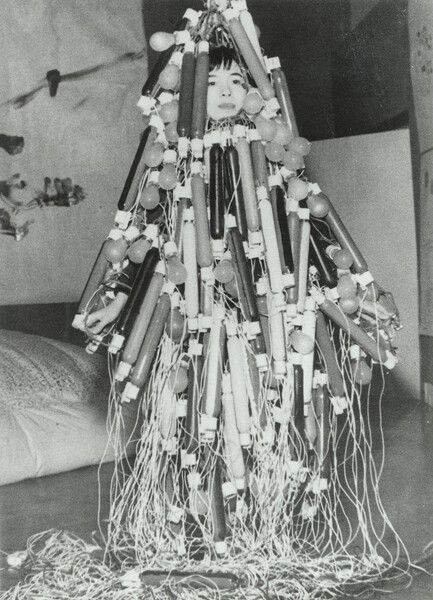

In the preface to his 1967 A Year from Monday, John Cage explored how electronic media has extended the human mind beyond the individual and made it social. “I believe—and am acting upon—Marshall McLuhan’s statement that we have through electronic technology produced an extension of our brains to the world formerly outside of us.”3 The human nervous system is no longer inside us but out there where electronic media let us join our electric friends in virtual environments.

Half a century later, popular culture and art overflows with fantasies of simulated worlds and virtual spheres, while the corporate tech avant-garde launches optical instruments that promise no less futuristic electric dreams. One of today’s most vociferous techno-optimists, Kurzweil, spells out his prophecy: “By the end of this decade, we will have full-immersion visual-auditory environments, populated by realistic-looking virtual humans. These technologies are evolving today at an accelerating pace… By the 2030s, virtual reality will be totally realistic and compelling and we will spend most of our time in virtual environments… We will all become virtual humans.”4

All vision derives from light bouncing off our eyes, and based on the wavelengths of this light, our brain translates it into images. Yet new mixed reality devices that project information directly onto the retina, tricking the eye into believing it sees things out there in the world that do not exist in physical space, are still unsettling. What is it with eyes that makes the idea of manipulating them such an uncanny thought?

Ever since Sigmund Freud’s analysis of German Romantic writer E. T. A. Hoffmann’s terrifying story The Sandman (1816), who was said to steal the eyes of children, a physical attack on the eyes has been a recurring theme in art and literature, from surrealism to science fiction. The obsession with the eyeball has been at the center of visions that often explore all the traumas associated with losing one’s sight, with Georges Bataille and Luis Buñuel being the modernist virtuosos of violent ocular fixations. But it was Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) that revisits all the themes from Hoffmann’s dark tale and takes this eyeball anxiety to a new level. We are told that replicants—human as well as animal—are equipped with synthetic eyes that give off an orange glow. Eyes also play a key role in the film’s so-called “Voight-Kampff” test, where fluctuation of the pupil and involuntary dilation of the iris indicate the capability of empathy—and thus humanness. The optical instruments, artificial eyes, and desirable automatons of dark romanticism return in the film’s recent sequel. Set twenty-five years in the future, the world of Blade Runner 2049 is inhabited by holograms and mixed reality creatures . The virtual and the real have merged into a sinister amalgamation.

The ever-accelerating progress of technology will, according to Kurzweil, culminate in the Singularity, the almost vertical phase of exponential growth when technology seems to be expanding at infinite speed. This imminent event appears to be an acute break in the continuity of progress, but only, says Kurzweil, when we view the development from our current finite perspective. The Singularity will represent a total transformation of our ability to understand.

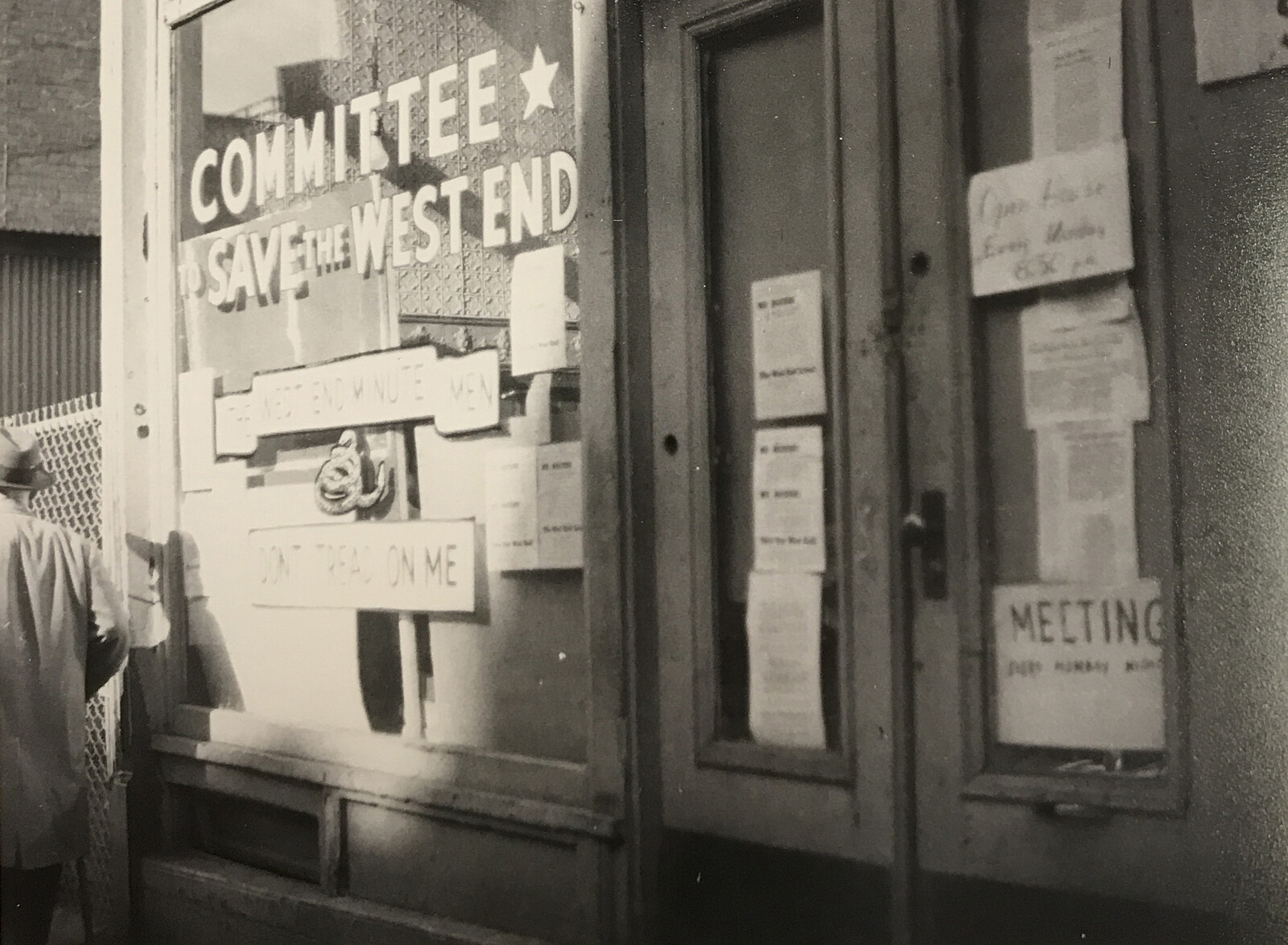

Against this sanguine idea of a messianic moment in which the entire planet becomes intelligent, critics of contemporary capitalism scrutinize how today’s digital technologies form the foundation of a surveillance economy that make possible the expropriation of critical human rights. As spelled out by Zuboff, it is necessary to establish new zones of resistance and creative friction: “We need to break the spell of enthrallment, helplessness, resignation, and numbing. This is best done when we bend ourselves towards friction, rejecting the smooth flows of coercive confluence.” Surely the Age of Surveillance Capitalism will end, she concludes, even if we are living in a moment when its instrumentarian power appear to be invincible. What is art and architecture to do in this context? Will they celebrate the possibilities of new visual technologies, and or will they be part of a new resistance? What side are you on?

Ray Kurzweil, The Singularity is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology (New York: Penguin Books, 2005).

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power (London: Profile Books, 2018).

John Cage, A Year From Monday: New Lectures and Writings (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1967), ix.

Ray Kurzweil, ”Foreword to Virtual Humans,” October 20, 2003, ➝.

Are Friends Electric? is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Moderna Museet within the context of its exhibition Mud Muses: A Rant about Technology.