Discourses about the possible alliance of art and technology have informed institutional projects across the history of modern art and contributed to the definition of art’s social logic and functions. What are the stakes of posing such an alliance today, at the moment of a global shift into a post-digital condition, where the digital paradigm exerts a defining influence over analog practices?

As further sectors of society are aligned with the production models and the social relations fostered by major digital platform companies, the production of ideology follows suit, offering a plethora of legitimizing as well as mystifying narratives.1 Here, critical discourse and corporate spin often verge toward indistinction. In the conceptual glut that results, it may be difficult to maintain one’s bearings, to chart the trajectory for a valid critical project.

Extrapolating from two institutional projects partly related to Moderna Museet in Stockholm in the late 1960s and early 1970s, two models of art-technology alliance may perhaps be discerned in the late-modern period of Western cultural production.2 The projects—one of which draws upon an early twentieth-century icon of avant-garde radicalism, and the other which anticipates a tradition of corporate art-technology collaborations to which institutional imagination remains largely consigned—both appear to premise the possibility of a progressive future for cultural production on the notion of an alliance of art with technology. Nevertheless, they represent two irreconcilable political positions. Does the account of these two models remain valid as a description of current conditions? If so, can the contradiction it articulates once again be rendered manifest as a site of possible conflict regarding the role of technology in shaping future democratic society?

Extension

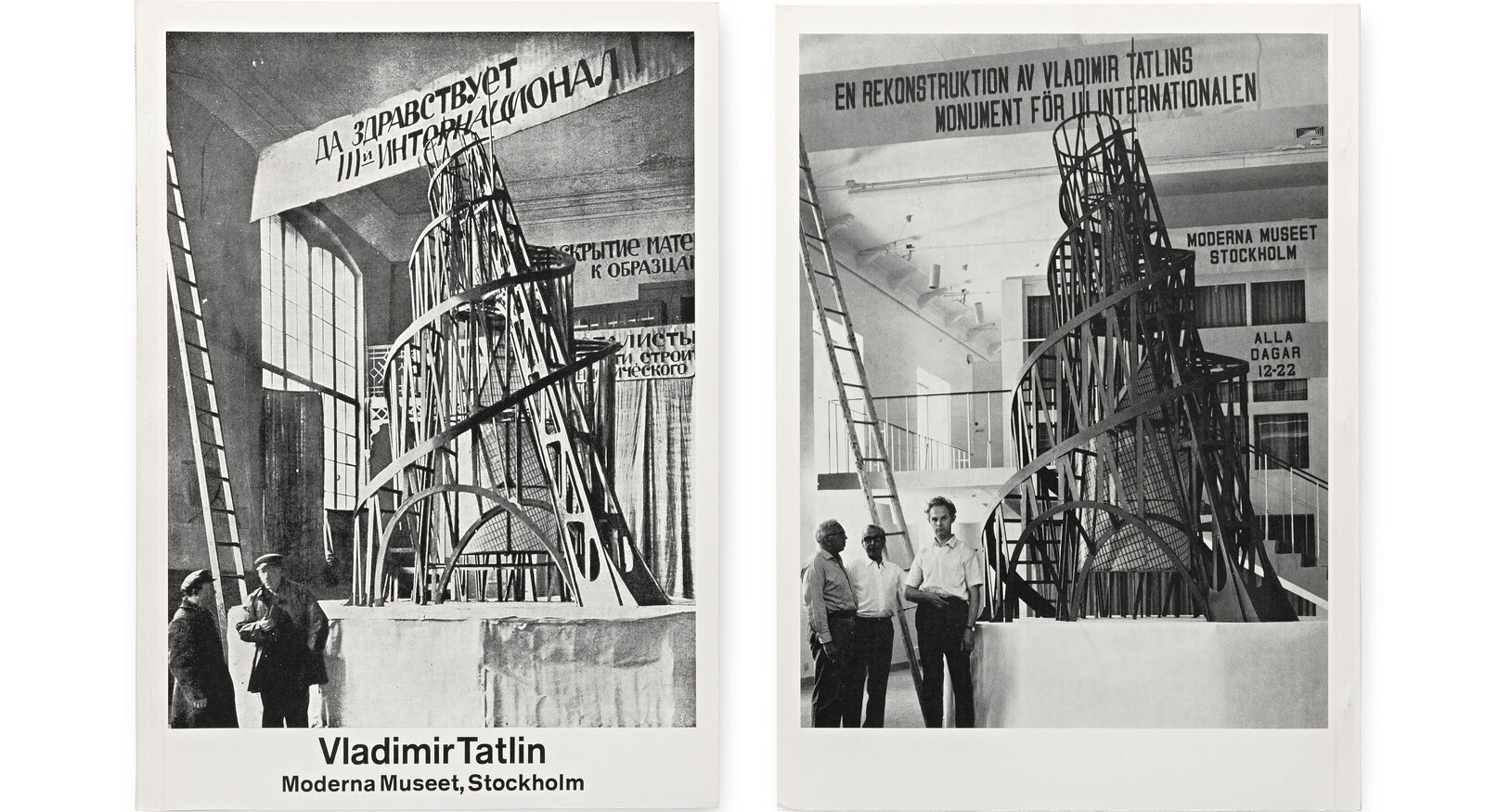

Exhibit A: the front and back cover of the catalogue for the exhibition Vladimir Tatlin, which was on view at Moderna Museet in Stockholm between July and September 1968. This was the first monographic exhibition with Tatlin’s work since the artist’s death in 1953, and it was one important factor contributing to his canonization as an icon for Western artists seeking a progressive alliance between art and technology at the turn of the 1960s.3

The front cover reproduces a famous photograph of Tatlin’s model for a Monument to the Third International shot in the artist’s studio in Petrograd (today St. Petersburg) in 1920. It shows Tatlin himself, together with a friend of his, standing below the model, which sits on a relatively high pedestal. The structure towers above the artist as its double helix arches triumphantly toward the ceiling. A wide banner, with the words “Long Live the III:rd International!” in Cyrillic capitals hangs above the model’s topmost segment. Two other banners are mounted on the railing of a mezzanine and on the wall in the picture’s background. Fragments of words can be discerned: “-matic,” “build,” “sample.” The room is flooded with light from a large window on the left side of the picture. Leaning against the wall next to the window is a tall ladder, intersecting at a low slant with the border of the picture plane.

The back cover features the same picture—but shot forty-eight years later by the photographer Hans Hammarskiöld inside Moderna Museet in Stockholm. In place of Tatlin and his friend stand three men: the carpenters and museum technicians Eskil Nandorf, Henrik Östberg, and Arne Holm, who had all collaborated on the reconstruction of the monument for the exhibition. Everything else is in the same arrangement, although the scale is slightly reduced: the tower’s double helix arches upward, a banner hangs above, other banners are mounted on a mezzanine in the background, light enters from windows on the left, and a tall ladder reclines against the wall, intersecting with the border of the picture plane.

The care with which the catalogue’s authors mimicked the 1920 photograph is evident. The two compositions mirror each other exactly, from the design of the text banners and the placement of the ladder to the postures of the figures in the foreground, the overall spatial arrangement, the camera position and framing, and the cropping of the picture. A logic of identification and repetition is at work, linking two historical moments. It is as if the organizers of the exhibition at Moderna Museet in 1968 had wanted to inhabit the photograph from half a century earlier—as if they had wanted to set themselves in that space, to assume those positions, to repeat its gestures, to rehearse those techniques.

Or, conversely, it is as if they had wanted to transpose Tatlin’s model from post-revolutionary Russia to their own contemporaneity, to Sweden at the complex moment of 1968. In the Swedish general election in September of that year, the Social Democratic Party won a majority of votes, securing another term in government and guaranteeing thirty-eight consecutive years as the country’s ruling party. But while the Swedish welfare-state project was then in full development, its internal contradictions were also becoming manifest. Redistributive measures, progressive housing policies, and large-scale infrastructural projects were not, it was widely perceived, working sufficiently to secure economic democracy, to facilitate civic codetermination, or to preclude urban segregation. An increasingly vocal new left seized upon these problems through different forms of social, political, and cultural organization, tapping into the energies unleashed by the global events of 1968.4 The welfare state, it was sensed, was not yet fully realized.

Back in 1920, Tatlin’s tower had been the model for a new kind of institution whose radical, technologically advanced architectural frame would support a multipurpose center for social assembly, political deliberation, and information dissemination. Among other things, the center would house the debating chamber of the executive committee of the Comintern, spaces for public assembly and discussion, and facilities for the processing and dispersal of political information, all set within revolving, geometric glass structures suspended inside the vast steel construction. The early conceptualization of the Monument to the Third International, as Maria Gough has remarked, “takes the form of something like a gigantic, mobility-mad, multitasking, spectacle-producing communication device dedicated to revolutionary agitation.”5

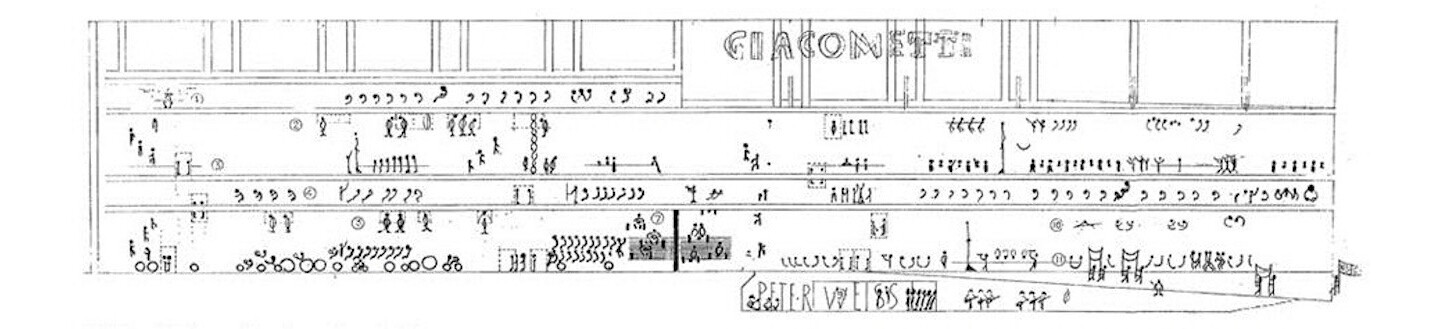

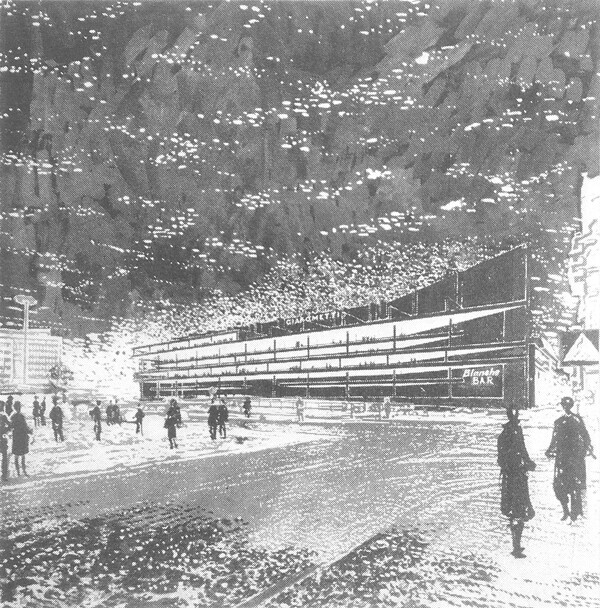

Peter Celsing, sketch of Kulturhuset façade, from Kulturhuset architectural competition entry, 1966.

So, why did the group behind Moderna Museet want to set up a kind of magic mirror to Tatlin’s model in their museum in 1968? It suggests that something more was at stake in their decision to mount the exhibition—which consisted of newly made reconstructions of Tatlin’s works, along with documents and reproduced images—than merely art-historical interest or neo-avant-garde nostalgia.6 It suggests that, in their view, a model like this could, mutatis mutandis, have some bearing on the problems and aspirations of their own moment, on how to conceive the role of cultural production in the unfinished project of the Swedish welfare state.

This, at least, was the wager that the group behind the Tatlin exhibition placed on the validity of the tower as a model. In October 1968, as the exhibition had just been dismantled, Moderna Museet finally entered into formal negotiations concerning a project that had been in development since 1963: to move the museum into new, purpose-built facilities at Sergels Torg, a public square in the center of Stockholm. In the process, the museum would be transformed into a new kind of multipurpose art center adequate to the artistic demands, technological conditions, and social challenges of its moment. That new institution, the group behind the project argued, should serve as “a catalyst for the active forces in society” and extend the democratic promises of modern Swedish cultural policy into new social fields.7 The center would be called Kulturhuset, the Culture House. The building, designed by the architect Peter Celsing, was already in an advanced stage of development when negotiations to move the museum there began to move forward.

Peter Celsing, sketch of Kulturhuset at night, from Kulturhuset architectural competition entry, 1966.

The plans outlined by the group in charge of formulating a program proposal for the new center drew explicitly on the structural and functional organization of Tatlin’s tower.8 The Monument to the Third International was designed as a polyvalent edifice that would integrate several different functions in one coherent totality. As Mark Wigley has recently noted, the tower would have operated as an enormous, four-stage filtering and transmission apparatus in which political proposals developed by the congress assembling in the lower section of the structure would be filtered up to the Comintern executive committee, which would convene at the second level. The committee’s decisions would then be filtered up to the information and propaganda center on the third level, which would process the data, and then filter it up to the fourth level, from where it would be broadcast across the city, the nation, or even the world, using radio transmitters and giant film projectors.9

Similarly, Kulturhuset, according to the early program proposals, would be structured as an enormous, radically democratic processing and transmission apparatus, something like the combination of a modern art museum, a commune, and a multimedia broadcast station. On the street level of the building, opening onto a public plaza, there would be an influx of information available for visitors on media devices and reading stations. The facilities would be equipped with basic artistic tools and materials, as well as state-of-the-art technologies such as tape recorders and film cameras, with which visitors were invited to process the information. The resulting cultural artifacts would be filtered up to the second level, a calmer environment in which visitors could read, study, look at videotaped TV shows, listen to a lecture by Marshall McLuhan (one of several possible guests to the center, listed already in a 1966 article about the project), or enjoy a drink from the bar.10

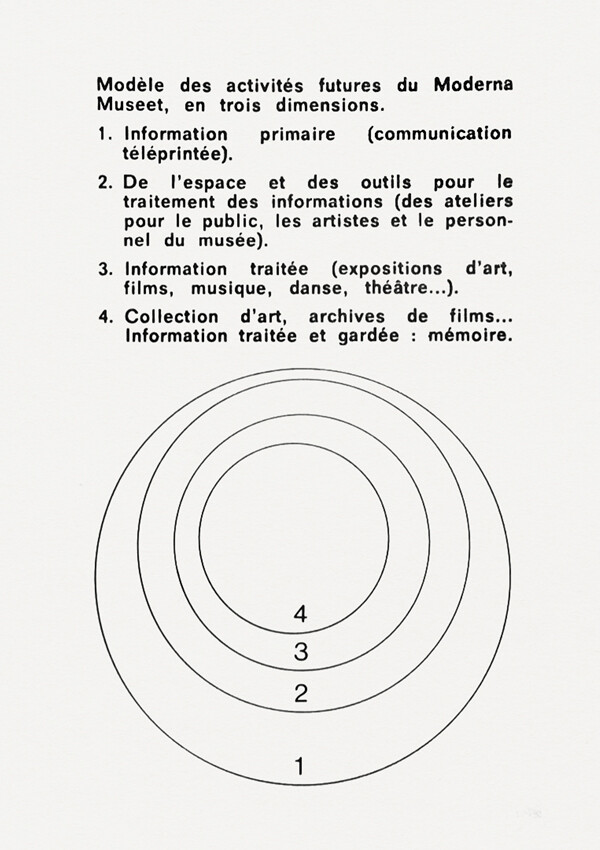

Pontus Hultén and Pär Stolpe, ”Model of the future activities at Moderna Museet”, Opus International, 1971. “1. Primary information (such as teleprinter messages); 2. Space and tools for processing the information (studios for the public, artists, and museum staff); 3. Processed information (art exhibitions, films, music, dance, theater…); 4. Art collection, film archive… Stored processed information: memory.”

Selections of the processed cultural artifacts would then be filtered up to the third level, where they would be reconfigured and displayed in the center’s main exhibition spaces. Some of the exhibited elements would then in turn be filtered up to the fourth level that would house the museum’s collection, conceptualized as the living memory of the institution, from where elements could also feed back down to the lower levels of the center. The whole structure was designed by Celsing as a giant “TV screen” whose expansive glass facade would serve as a media interface at the scale of the city, beaming the contents of the center across the surrounding urban landscape.11

Tatlin’s tower also stood as a quasi-utopian model for how to integrate political, cultural, and educational functions. In early descriptions of the project, the structure’s Comintern facilities would sit alongside an idiosyncratic range of other amenities, such as gyms, “agitation centers,” and typographic workshops.12 The determining juxtaposition of the structure, however, was its functions as a seat of political deliberations and as a transmission center for political and educational information. The tower was essentially a parliamentary building set within a gigantic public-service radio mast.

Kulturhuset as temporary house of parliament, interior, early 1970s.

Remarkably, these aspects were also mirrored nearly exactly in the Kulturhuset project. By a series of coincidences and negotiations it had been decided that the building at Sergels Torg should also serve as the temporary seat of the Swedish parliament while the original parliamentary buildings underwent renovations and reconstructions.13 Throughout the period when the Moderna Museet group developed their program proposal for the new center, they were fully aware that their multipurpose institution would sit alongside the offices and meeting chambers of the members of Swedish parliament, and they integrated that adjacency into their conception of the project. The new center, wrote Pär Stolpe, one of the key authors of the proposal, should give visitors the “opportunity to realize themselves with the possibility of direct access to their political representatives.”14

The reasons Moderna Museet wound up never moving into the new building at Sergels Torg—so that the vision, as it were, of erecting a monument to the Third International in the center of Sweden’s capital was left unrealized—were mostly mundane, having to do with the inability of politicians at state and municipal levels to collaborate.15 Aside from serving as a provisional house of parliament for twelve years, Kulturhuset became a dysfunctional compromise between a range of municipal cultural institutions, which it remains to this day. But the group behind Moderna Museet’s program proposal did not abandon their project. Instead, they adapted it into a plan for how to renew the museum’s existing institutional organization and facilities at Skeppsholmen in Stockholm. In the process, they radicalized their model in several respects.

Installation shot, Women, curated by Group 8, at Filialen, Moderna Museet, 1972. Photographer: Mikael Wahlberg. Source: Moderna Museet Rights and Reproductions.

Their updated proposal emphasized the project’s reliance on the possibilities afforded by new information technologies. In the new model, outlined by Pontus Hultén and Pär Stolpe in the spring of 1970, the notion of a layered organizational structure, supporting a process of gradual filtering across four stages, was maintained. But that model—which mirrored the structure of Tatlin’s tower—was now mapped onto a rudimentary, highly abstract diagram of an information processor. Hultén and Stolpe illustrated their proposal with a simple image depicting four circles lodged one inside the other. Rather than a vertical movement through a pile of monumental glass structures, as in the tower, or across a stack of open, flexible floor planes, as in the Kulturhuset proposal, the movement would here be centripetal and centrifugal, leading from the outer layer of the four circles toward the core and then out again.

The diagram’s outer circle, Hultén explained in different interviews from the period, should be seen as an information-capture layer.16 Here “primary information” would be available, an unedited flux of data streaming in through different channels, such as telex printers, news-agency reports, and videophone terminals. This department of the museum, Öyvind Fahlström wrote in a commentary, would be equipped so as to be technically “superior to the central newsroom of Swedish Television.”17 The second circle would be a processing layer. Here, tools and instruments for treating the captured information would be accessible to the public: video-editing bays, offset-lithography machines, and computers. The third circle, in turn, would be an interface layer: exhibition spaces where the processed information could be edited, arranged, and displayed. Finally, the fourth circle, the core, would be the center’s memory or database: the collection, to which selections of the exhibited works would be transferred for storage and reuse. One purpose of this museum conceived as an “information center,” Hultén stated, was critical: “Protection against predigested information. Resistance to monopolies.”18

The information-center model served as the most general blueprint for the comprehensive institutional reorganization planned for Moderna Museet in the first years of the 1970s. Once again, that reorganization was never fully realized, but the period remained one of intense innovation at the museum, as its staff experimented with new modes of exhibition making and public programming in anticipation of the new structure.19 Key ventures during the period included devising exhibition formats and modes of distribution adequate to the new status of the artwork in a burgeoning age of computerized reproduction, when advanced information technologies were transforming the conditions of production, interaction, and transmission in the cultural field and beyond.

Installation shot, The Power of Music, at Filialen, Moderna Museet, 1973. Source: Moderna Museet Rights and Reproductions.

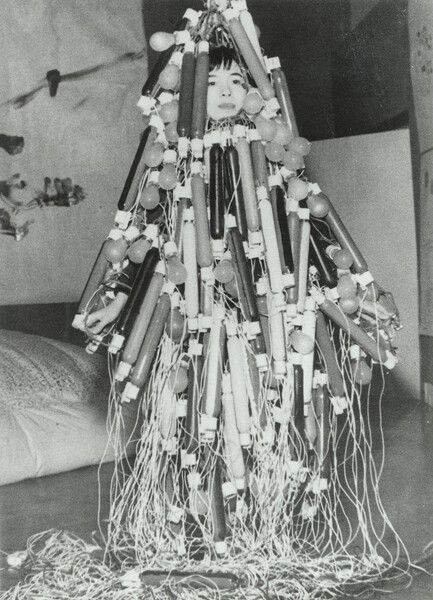

A temporary annex to Moderna Museet called Filialen was specifically set up for conducting such experiments. Directed by Pär Stolpe, Filialen housed some of Moderna Museet’s most significant exhibitions of these years, such as Women (1972), the museum’s first feminist initiative, organized by the collective Group 8, or For a Technology in the Service of the People (1972), an exhibition on alternative, eco-political uses of new technologies, organized in collaboration with the PowWow collective and the Radical Technology pioneer Peter Harpe and scheduled to serve as a counter-manifestation to the enormous, World Bank-sponsored UN Conference on the Human Environment that took place concurrently in Stockholm.20 Throughout, the intense program at Filialen emphasized quick and low-cost production techniques, networked organizational models, and scalable, reproducible, and transmissible materials and supports, forming a “mobility-mad, multitasking, spectacle-producing communication device dedicated to revolutionary agitation,” to repurpose Gough’s phrase about Tatlin’s tower.

As Peter Osborne has recently suggested, the central problematic of the “Soviet experience” in the arts during its “productive phase”—what has been canonized as the near-utopian, post-revolutionary moment of the Monument to the Third International—was “not anti-art-institutionalism,” but “socially alternative modes of the institutionalization of art.” The political meaning of modern art, Osborne argues, “resides in its image of freedom: the prefiguration of a free praxis, or praxis in a free society.”21 The artists of that “productive phase,” then, did not seek to realize the freedom of art by negating it and transcending it as a separate institutional sphere in society, in accordance with the familiar avant-garde dialectic. Instead, they sought socially alternative modes of organizing art’s institutional field so as to extend the reach of the free praxis it prefigured.

In a way, this was also what was on display, and at stake, in the magic mirror Moderna Museet held up to that productive experience half a century later. With their institutional experiments during the period, the Moderna Museet group sought to respond to two general questions. First, how could new technologies be deployed so as to extend the scope of free praxis, that is, of individual and collective self-determination, prefigured in the modern artwork? Second, how should a renewed art-technology alliance be socially institutionalized in order to serve that end? That is, how should social and cultural policies be designed so as to support the extension of free praxis, and how could a new type of art-technology institution be devised to function as a catalyst in that process?

Or, in short, how could new technologies extend the freedom promised by art, and how should the new alliance of art and technology be socially organized so as to contribute to the realization of that freedom? The attempts to answer that question could be described as the radically democratic tradition within the history of the art-technology alliance.

Concentration

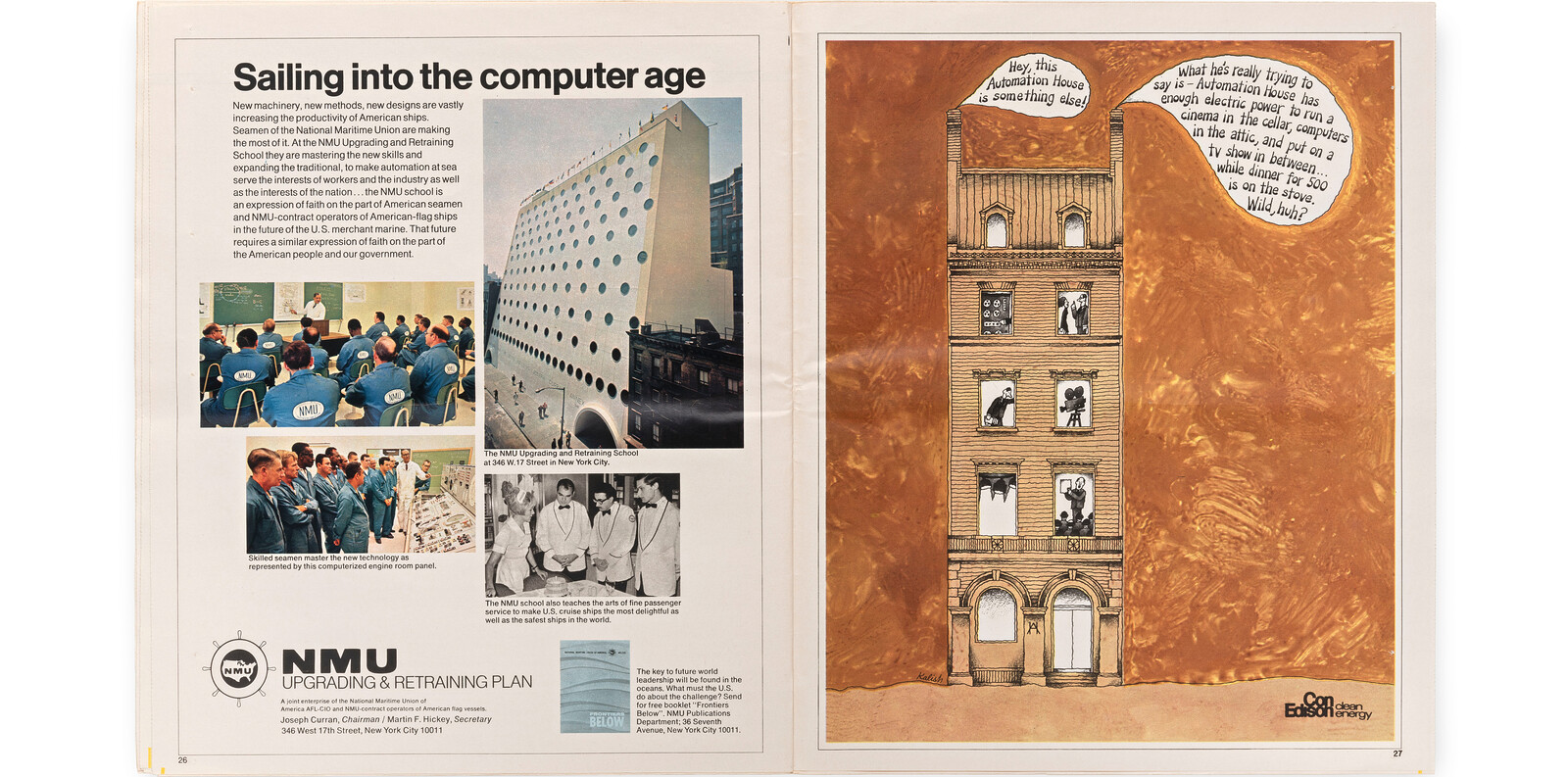

Exhibit B: the broadsheet folder Automation House, published as an insert in the New York Times on February 1, 1970. Produced by an association of three New York–based organizations—The American Foundation on Automation and Employment, E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), and the Institute of Collective Bargaining and Group Relations—the exquisitely designed folder advertised their new joint headquarters, named Automation House, a new “multipurpose communal center of communications” located in a refurbished six-story, nineteenth-century building on East 68th Street in New York City.22

The cover of the folder features a watercolor by Robert Rauschenberg, who was one of the founders of E.A.T. together with the Swedish engineer Billy Klüver and fellow artist Robert Whitman. The image is a combine of sorts. In the background are fragments from photographs showing a segment of the Automation House facade, a group of hardhat workers mounting a large pipe, and Theodore Kheel, Rauschenberg’s lawyer and the center’s president. Interspersed with these fragments are graphic elements: details from technical line drawings, figures from a statistical sheet, pre-printing match marks and color keys, and a schematic representation of a geodesic dome.

In the image, these different elements are painted over with broad strokes of washed-out watercolor in hues of white and blue. With their pastel palette, the light swathes of paint are laid like a patchy film onto the assembled pictorial fragments, smoothing out their abrupt juxtapositions. The harmonic coexistence of the different elements in Rauschenberg’s composition, we might say, was an adequate representation of Automation House’s confident vision of a peaceful cohabitation of artists, engineers, politicians, and industrialists within the spaces of their Upper East Side mansion.

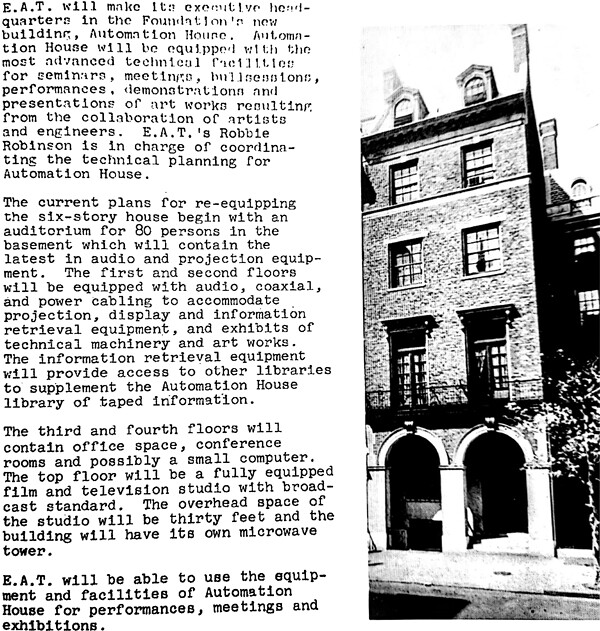

Automation House façade, from E.A.T. News 1, no. 3 (November 1967).

Across the stylish spreads inside the folder—designed by S. Neil Fujita—the House’s three organizations proudly presented their respective aims and activities. E.A.T. restated its oft-repeated pitch about seeking to match artists with engineers, citing a “strong belief that an industrially sponsored, effective working relationship between artist and engineer will lead to new possibilities benefiting society as a whole.”23 In evidence, they provided a list with short descriptions of their prior and ongoing projects: the infamous 9 Evenings performance series at the 69th Regiment Armory in Manhattan in October 1966 (“an experiment in sociology,” Jack Burnham sternly reported, “since it would take a particularly perverse audience to sit through and endure anything so feeble”); the exhibition Some More Beginnings at the Brooklyn Museum in 1968; and the already notorious Pepsi Pavilion at the Expo ’70 world exhibition in Osaka, the preparations for which were in their most chaotic phase at the time the folder was created.24

“Change is inevitable,” The American Foundation on Automation and Employment in turn stated. Directed by Kheel, an influential labor mediator, the Foundation gathered industrial leaders, trade-union representatives, politicians, and corporate lawyers who had major stakes in mapping the possibilities and challenges of industrial automation. The prospect of intelligent machines and self-learning systems assuming increasingly complex tasks in the production process provoked unease among shop-floor workers and middle management alike. Everyone was afraid that they stood to be replaced by robots and computers. At the same time, the Foundation maintained, automation was a source of potential good, a step forward in the steady march of technological rationalization. Provided that the employment problem could be solved, it “holds the unique promise of a truly new world.”25

The terms in which the Foundation framed this problem could be applied, mutatis mutandis, to the debates on the virtues and vices of robotization and artificial intelligence today, half a century later. “People living in advanced economies are anxious about the sweeping impact of technology on employment,” reads the World Bank’s 2019 report, The Changing Nature of Work, mirroring the language of the Automation House folder. “And yet technology provides opportunities to create new jobs, increase productivity, and deliver effective public services.”26 To profit from these opportunities, the World Bank proposes its Human Capital Project, designed to educate workers in advanced cognitive and sociobehavioral skills unlikely to be fully automated in the near future, such as complex problem-solving and teamwork. As the vice president of General Electric had noted already back in the 1950s, automation is inevitable, but “it takes a lot of hard work and sacrifice by a lot of people to bring about the inevitable.”27

In 1970, the organizations behind Automation House outlined two general solutions to the automation-employment problem. First, invest in job-training programs proper to the new conditions, continuously adapting the labor force to rapidly changing production techniques, mutating consumption patterns, and concomitant labor-market shifts: “training for the jobless who are unskilled and re-training for the skilled who are displaced.”28 It remained an open question how those programs should be designed, and the Foundation was devised precisely for the exchange of ideas regarding such issues. Second, properly identify the concerns of both labor and management and create the conditions favorable for mutually beneficial negotiations, presumably through lobbying. Here the Foundation was assisted by The Institute of Collective Bargaining and Group Relations, an association of industrial representatives, politicians, and trade unionists also headquartered at the center.

What was needed, in short, was to forge a culture of innovation, enterprise, and cooperation adequate to the changes brought about by accelerated automation. E.A.T.’s open-ended brief about promoting a “civilized collaboration” between artists and engineers, in order to “encourage industrial initiative in generating original forethought” and so “avoid the waste of a cultural revolution,” made them perfectly suited for the purpose.29 And Automation House was set up as a highly versatile and flexible platform for such experimentation, compatible with a bewildering range of activities and needs.

The house, an early announcement of the project explained, would be “equipped with the most advanced technical facilities for seminars, meetings, bullsessions, performances, demonstrations, and presentations of artworks resulting from the collaboration of artists and engineers.” In the basement of the building there would be an eighty-seat auditorium with “the latest in audio and projection equipment.” The floors above would be resourced with “audio, coaxial, and power cabling,” as well as “information retrieval equipment” providing “access to other libraries,” and “possibly a small computer.” The building, finally, would have “its own microwave tower.”30 “In a matter of minutes,” a text in the Automation House folder explained,

Automation House can be turned from a forum on collective bargaining to a museum exhibiting the collaborations of artists and engineers; from a competition in its MULTITORIUM of motion picture entries in the Job Film Fair to a testimonial dinner saluting the award winning films; from a collective bargaining session to the mediation of a community dispute; from a class or seminar on job training to a lecture on applied research to community problems; from an exhibition of computer-aided instruction to a closed circuit broadcast on job training… Automation House can function 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Within its four walls and through its electronic outreach, it has the capacity of a major seat of learning. The many activities of Automation House, each separate and distinct, blend into a sympathetic and interrelated collage of communications.31

With its peculiar combination of proto-neoliberal ideals of labor-market restructuring, social democratic measures for facilitating labor-industry agreements, and cyber-psychedelic transmedia art practices, Automation House was unavoidably a conflicted as well as contested operation, reflective of the social oppositions of its moment. Its fundamental contradiction, or perhaps confusion, which also cut straight through E.A.T.’s program, had to do with the political implications of its model for an art-technology alliance and the notion of automation that served as its guiding idea.

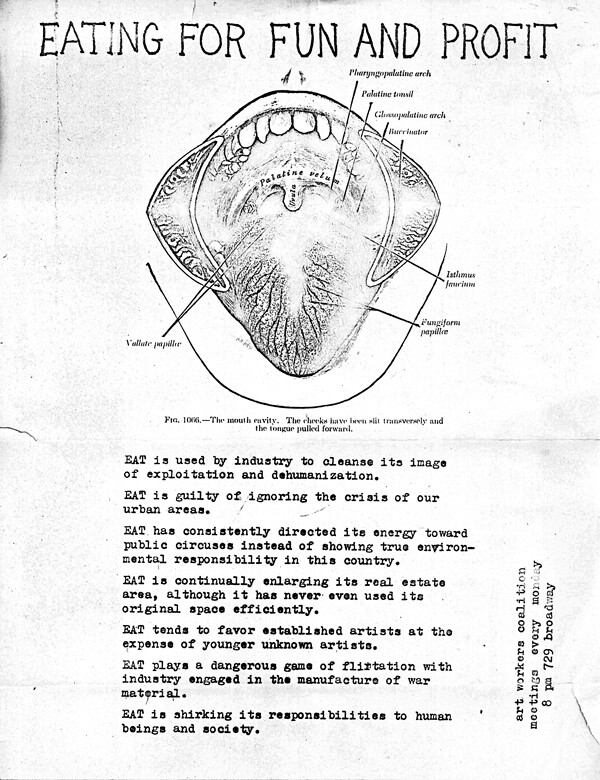

”Eating for Fun and Profit,” leaflet, Art Workers’ Coalition, 1970. Source: Moderna Museet Rights and Reproductions.

On the one hand, the concept of “automation” inherently evoked the promise—at once utopian and undeniably realist—of a world beyond work, where machines and systems would carry out the menial tasks necessary for basic subsistence and safety and the human being would be liberated from the compulsion of productive labor, making it possible for them to enjoy their existence in its non-alienated fullness as free play. By calling upon this concept, Automation House associated itself—however tangentially—with a late-modern legacy of post-work imaginaries, including such movements as the Situationist International, with its exhortation to “never work” and its visions of an automated city, or Italian operaismo, with its “strategy of refusal” of the labor form.32

On the other hand, the dominant logic of “automation” at Automation House, that which effectively governed its project and overall organization, was the rationalization of the means of production within the framework of intra-capitalist competition. Here, the alliance of art and technology could be deployed for several associated ends. It could serve to infuse high-tech corporations with creativity, contributing to the invention of new competitive skillsets among engineers or to the discovery of new markets for consumer goods. That, however, appears rarely, if ever, to have actually succeeded throughout the history of corporate art-technology collaborations. Or it could serve to provide marketing or brand value, associating the firm and its products with the exclusive allure of avant-garde uniqueness and originality—which is the model that has claims to economic efficiency, however mediated and indirect. Automation House, in this sense, anticipated nothing so much as the “creative hubs” or “business incubators” of Silicon Valley.

The logic of the art-technology alliance at Automation House therefore ran counter to the logic at work in Moderna Museet’s Information Center plans, developed at the same time. There, the guiding questions were how technology could be deployed so as to extend the free praxis prefigured in the artwork, and how a new art-technology alliance could be socially institutionalized so as to contribute to the realization of that freedom. The model was one of radical democracy, of the extension of individual and collective self-determination. This was not science fiction or utopianism, but a realpolitik model borne out of a specific and short-lived conjuncture of Swedish welfare state experimentalism, and aligned with many of the ideals outlined in the new Swedish cultural policy that was being drafted during the same period.33

The experiments at Automation House went in the opposite direction. Rather than seeking to extend the free praxis prefigured in the artwork into further social fields, the art-technology alliance at Automation House was a stratagem for uncovering new zones of praxis—this was what the creativity of the artist was mined for—that could be enlisted for increasing competitiveness and consequently serve as sources of potential revenue, of private wealth. The prospect of automation called for the invention of new skills and methods for the production of value, and art was engaged for that end. The industry-labor associations at Automation House could bargain valiantly for mitigating the corrosive effects of this “inevitable” process on employment rates and salary levels, but they were not there to propose alternatives to it, or even to question it.

It is important not to reductively conflate different levels here. Judging from the few sources that can be readily accessed, at a practical level the artistic program at Automation House appears to have been radically open, featuring, for example, a wide range of innovative experiments with new sound technologies, closed circuit television systems, cable broadcasting programs, and global information networks, by artists and composers such as Robert Whitman, Stanley Landsman, and Terry Riley.34 At the level of the social logic of its institutional model, however, the art-technology alliance at Automation House sought to integrate art in capitalism’s dynamic of reinvention in the face of technological change, ultimately aiming to sustain the unequal social relations on which that dynamic feeds. Rather than an extension of democracy and equality, in other words, the logic was one of the concentration of power and wealth.35

We might call this simply the oligarchic model, and while it may be difficult to imagine a workable substitute for it today, it is perhaps not as difficult as it has been over the past decades of neoliberal hegemony. In fact, our present moment sees a renewed interest in models for rethinking the social function of advanced technological infrastructures, as evidenced by recent proposals for “socialized data centers” and “feedback infrastructures,” the creation of publicly owned “postcapitalist platforms,” or even, at the further end of the spectrum, a “fully automated luxury communism.”36 I do not seek to arbitrate between such new imaginaries of a reinvigorated left, but simply point out that they draw upon a legacy of radically democratic experimentation that can no longer be afforded not to defend and pursue.

Conclusion

The historical moment of Moderna Museet’s Information Center plans and the launch of Automation House in New York City was a moment of crisis for Western art institutions. New artistic techniques, new modes of visitor behavior, new patterns of media use, new technological conditions, and new social forces all contributed—it was widely sensed—to rendering the art museum and the art gallery in their established forms obsolete.37 The Information Center and the Automation House projects can both be seen as attempts to respond to that crisis. Their different institutional models for art-technology-alliances both sought to circumscribe active functions for art in a changing, increasingly dynamic social reality.

One often repeated argument in recent critical discourse holds that the forms and the values introduced by the progressive arts movements of the 1960s and 70s—values such as transparency, flexibility, dynamism, and interactivity—in fact worked against their intended purposes. Rather than ushering in a new era of extended democratization and civic co-determination, they prepared the ground for the restructured production methods and the fluid power arrangements of neoliberal capitalism. Rather than facilitating increased equality and autonomy, they set the stage for post-Fordist labor relations and control society. The dream of the counter-culture—so the argument goes—was realized as the new spirit of capitalism.

This is a neat, even comfortable argument, and—to refer to a canonical text in the context—there is no doubt that what Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello called “artistic critique” did serve a role in providing conceptual and technical models for the remodeling of the social structures of capitalism during the 1970s and 80s.38 But there is a risk that this argument blurs distinctions, instead of elucidating their logic. It may lead to the effects of a process of counter-reform and co-optation being mistaken for the preceding project of emancipatory reform. It may lead to a history of contradiction and conflict being replaced with a determinist narrative of “inevitable” political and economic development.

Of course, there was nothing inevitable about that development. Irreconcilable cultural and political positions confronted one another. The development, establishment, and naturalization of the neoliberal paradigm required—and continues to require—a massive political and ideological effort. What is important, therefore, is to not reduce the contradiction. One way of phrasing this here could be to note that, during the years of the full deployment of the neoliberal project from the late 1970s onwards, the Automation House model came to be favored above the Information Center one. That is, institutional models staking their legitimacy on art’s possible function as a source of creativity or brand value for post-industrial corporations seeking to regain competitiveness were sanctioned at the expense of models seeking to extend the social reach of art’s inherent promise of free praxis through cultural policy initiatives. The fact that both institutional models can be described using the same terms—as flexible, dynamic, responsive, and so on—does not reduce the differences between them.

Critical discourses that accuse the “counter-culture” of inadvertedly preparing the ground for neoliberalism’s “stealth revolution”—to borrow Wendy Brown’s term—are collapsing these two models onto one another.39 In doing so, they are contributing to the dissimulation of their opposition, and consequently to the repression of the legacy of radical democracy. However critical in intent, such readings serve to naturalize the predominance of the oligarchic model for defining art’s social role. Conversely, keeping the contradiction in view, following its modulations, and mapping its different mutations are conditions for the possibility of once again rendering it active as conflict, setting the extension of the domain of autonomy against its obliteration.

On the increasing dominance of the digital platform firm in today’s global economy, see Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). Regarding the encroachment of behavioral protocols fostered by contemporary digital media on everyday habits and social relations, see Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (London: Verso, 2013).

This essay draws partly on research conducted for my PhD dissertation, The Exhibitionary Complex: Exhibition, Apparatus, and Media from Kulturhuset to the Centre Pompidou, 1963–1977, Södertörn Academic Studies, 2017.

Vladimir Tatlin, Moderna Museet Exhibition Catalogue no. 75 (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1968). Works by Tatlin had been included in several important exhibitions of Russian constructivist art in Europe and the US during the 1960s, but the Stockholm exhibition, curated by Carlo Derkert and Pontus Hultén in collaboration with Troels Andersen, a Danish art historian and specialist in Russian constructivism, was the first monographic exhibition of Tatlin’s work since the artist’s death in Moscow in 1953.

See, e.g., Werner Schmidt, “From Fordism to High-Tech Capitalism: A Political Economy of the Labour Movement in the Baltic Sea Region,” in Norbert Götz, ed., The Sea of Identities: A Century of Baltic and East European Experiences with Nationality, Class, and Gender (Huddinge: Södertörn Academic Studies, 2014), and Helena Mattson, “Where the Motorways Meet: Architecture and Corporatism in Sweden 1968,” in Mark Swanerton, Tom Avermaete, and Dirk van den Heuvel, eds., Architecture and The Welfare State (London: Routledge, 2014).

Maria Gough, “Model Exhibition,” October 150 (Fall 2014): 13.

Alongside the reconstruction of the tower, the exhibition featured reconstructions of a counter-relief and a chair borrowed from museums in Portmouth and Newcastle. On the history of reconstructions of Tatlin’s tower, of which Moderna Museet’s was the first, see Nathalie Leleu, “‘Mettre le regard sous le contrôle du toucher’: Répliques, copies, et reconstitutions au XXe siècle: les tentations de l’historien de l’art,” Les Cahiers du Musée National d’Art Moderne 93 (Fall 2005). Peter Bürger introduced the notion of the “neo-avant-garde” as nostalgic, depoliticized repetition of the heroic historical avant-garde in Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984). Moderna Museet’s mirroring of the tower in 1968 more justly evokes Hal Foster’s reading of the same concept in “Who’s Afraid of the Neo-Avant-Garde?” in The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), according to which it is through the neo-avant-garde repetition of the historical original that the original becomes itself, that its project is first enacted.

Carlo Derkert, Pontus Hultén, Pi Lind, Pär Stolpe, and Anna Lena Thorsell, “Skrivelse från expertgruppen den 5 januari 1969,” in Om kulturhuset: Kulturlokalerna vid Sergels Torg, Kulturhuskommitténs slutrapport, Kommunstyrelsens utlåtanden och memorial 49 (Stockholm: Kommunstyrelsen, 1971), 52.

For example, Carlo Derkert, educator and curator at Moderna Museet and one of the members of the “expert group” working on the program proposal for the new institution, noted that the new center’s vision of a coherent “unitary function” drew on “Tatlin’s tower for the 3rd intnl.” Derkert, “Musei II Moderna idéer,” Carlo Derkert Archives, National Library of Sweden, 2009/94:3:25.

Mark Wigley, Buckminster Fuller Inc.: Architecture in the Age of Radio (Zürich: Lars Müller Publishers, 2015), 32f.

See Pontus Hultén, “Stockholms kulturella vardagsrum,” Dagens Nyheter, November 29, 1966.

See Peter Celsing, “Förslagsställarens beskrivning,” in Resultat av allmän nordisk idé-tävling om bebyggelse inom kvarteren Fyrmörsaren, Skansen och Frigga söder om Sergels torg i Stockholm (Stockholm: Stadskollegiet, 1966). See also Celsing’s comments in “‘Stadsmur’ skall dela Stockholm: Peter Celsing vann klart tävling om Sergels torg,” unsigned, Dagens Nyheter, July 5, 1966.

See Nikolai Punin, “On the Tower” {1919}, trans. Troels Andersen and Keith Bradfield, in Vladimir Tatlin, 56.

See, e.g., Anders Gullberg, City – drömmen om ett nytt hjärta: Moderniseringen av det centrala Stockholm 1951–1979, vol. 2 (Stockholm: Stockholmia förlag, 2002), 134.

Pär Stolpe, “Några ord om Kulturhuset i Stockholm,” undated manuscript, early 1970s, §9. In Pär Stolpe personal archives, folder “Moderna Museet, reconstruction.”

The definite collapse of the negotiations was formally announced in a press release signed by members of both delegations on February 27, 1970. Stockholm City Archives, 0218/B:2.

See, e.g., Yann Pavie, “Vers le musée du futur: entretien avec Pontus Hultén,” Opus International 24–25 (May 1971), which also features a version of the diagram with four circles.

Öyvind Fahlström, “Moderna Museet – Från pompa och ståt, till informationscentrum,” in Olle Granath and Monica Nieckels, eds., Moderna Museet 1958–1983, (Stockholm: Moderna Museet, 1983), 171.

Pierre Gaudibert, Pontus Hultén, Michael Kustow, Jean Leymarie, François Mathey, Georges Henri Rivière, Harald Szeemann, and Eduard de Wilde, “Exchange of Views of a Group of Experts,” Museum XXIV, no. 1 (1972): 14. The Information Center model went on to exert an important influence over the early conception of the Centre Pompidou. These developments are described in detail in my dissertation, referenced above, note 2.

See, e.g., the texts about the renovation collected in Arkitektur, vol. 77, no. 3, April 1977. See also Eva Eriksson, “Förvandlingar och lokalbyten: Moderna Museets byggnader,” in Anna Tellgren, ed., Historieboken: Om Moderna Museet 1958–2008 (Stockholm/Göttingen: Moderna Museet/Steidl, 2008).

On For a Technology in the Service of the People, see Felicity Scott, “Woodstockholm” and “Battle for the Earth,” in Outlaw Territories: Environments of Insecurity/Architectures of Counterinsurgency (New York: Zone Books, 2016).

Peter Osborne, “Theorem 4. Autonomy: Can It Be True of Art and Politics at the Same Time?” in The Postconceptual Condition: Critical Essays (London: Verso, 2018), 68ff, emphasis original.

“Automation House: A Philosophy for Living in a World of Change,” in Frank Saunders, ed., Automation House, advertising supplement to the New York Times, February 1, 1970: 2.

“Experiments in Art and Technology,” in Automation House: 8.

Jack Burnham, “Art and Technology: The Panacea That Failed,” in Kathleen Woodward, ed., The Myths of Information: Technology and Postindustrial Culture (Madison: Coda Press, 1980). Burnham here relates the judgment of the critic Clive Barnes, noting that it “was more or less typical of the general audience response.” See also Calvin Tomkins, “Outside Art,” in Billy Klüver, Julie Martin, and Barbara Rose, eds., Pavilion (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1972), originally published in The New Yorker in 1970.

“American Foundation on Automation and Employment,” in Automation House: 5.

The Changing Nature of Work: 2019 World Development Report (Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2019), 2.

Quoted in David F. Noble, Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2011), 230.

“American Foundation on Automation and Employment,” in Automation House: 5.

“E.A.T. Aims” {October 1967}, reprinted in Anna Lundh and Julie Cirelli, eds., Visions of the Now: Catalogue (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2017), 18.

Julie Martin, ed., E.A.T. News 1, no. 3 (November 1, 1967): 9.

“Automation House: A Philosophy for Living in a World of Change,” in Automation House: 2.

See Constant, “Une autre ville pour une autre vie,” in Internationale situationniste 3 (December 1959), and Mario Tronti, “The Strategy of Refusal,” in Sylvère Lotringer and Christian Marazzi, Autonomia: Post-Political Politics (New York: Semiotexte, 2007).

See SOU 1972:67, Ny kulturpolitik: sammanfattning, Stockholm, 1972. It is also worth noting that Sven Nilsson’s Debatten om den nya kulturpolitiken, Stockholm: Allmänna förlaget, 1973, an official report on the debates around the proposal for a new Swedish cultural policy, commissioned by the Swedish Arts Council, features on its cover an image of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International. It would be interesting to read the cultural policy experiments of this moment in Sweden in the context of what Mark Fisher called “acid communism.” See “Acid Communism (Unfinished Introduction),” in k-punk: The Collected and Unfinished Writings of Mark Fisher, Darren Ambrose ed. (London: Repeater Books, 2018).

Some details about the programming can be found in Michelle Kuo’s podcast at the blog of the Silicon Valley “seed accelerator” Y Combinator, ➝. See also Gene Youngblood’s interview with Steina Vasulka, “Orbits of Fortune with Steina and Gene Youngblood,” Steina: 1970–2000 (Santa Fe: SITE, 2008), 4–5. Thank you to Adeena Mey for giving me access to this text. There is also a discussion about Automation House in Fred Turner, “Romantic Automatism: Art, Technology, and Collaborative Labor in Cold War America,” Journal of Visual Culture 7, no. 5 (2008), but he appears to draw his information almost exclusively from the Automation House folder. In 1971, Automation House was one of the nodes in the global telex network developed by E.A.T. for the exhibition Utopias and Visions: 1871–1981 at Moderna Museet in Stockholm. See Billy Klüver, “Projects Outside Art II,” in Barbro Schultz Lundestam, ed., Teknologi för livet: Om Experiments in Art and Technology (Paris: Schultz förlag, 2004), 180, and “Description,” in Utopia: Question and Answer: A Project for the Exhibition: “Utopia and Visions: 1871–1981” at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm, unsigned compendium, dated May 30, 1971. Moderna Museet Archives, F2oc:3.

See Noble, Forces of Production, 353.

Evgeny Morozov, “Digital Socialism? The Calculation Debate in the Age of Big Data,” New Left Review 116/117 (March–June, 2019), and “Socialize the Data Centers!” New Left Review 91 (January–February 2015); Nick Srnicek, Platform Capitalism; Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (London: Verso, 2015); Aaron Bastani, Fully Automated Luxury Communism (London: Verso, 2019).

One interesting document in this context is the “Exchange of Views of a Group of Experts,” based on discussions between a group of European museum directors, curators, and museologists in Paris in 1969 and 1970, quoted above, note 18.

See Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello, The New Spirit of Capitalism, trans. Gregory Elliot (London: Verso, 2005), 28f.

See Wendy Brown, Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (New York: Zone Books, 2015).

Are Friends Electric? is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and Moderna Museet within the context of its exhibition Mud Muses: A Rant about Technology.