Introduction

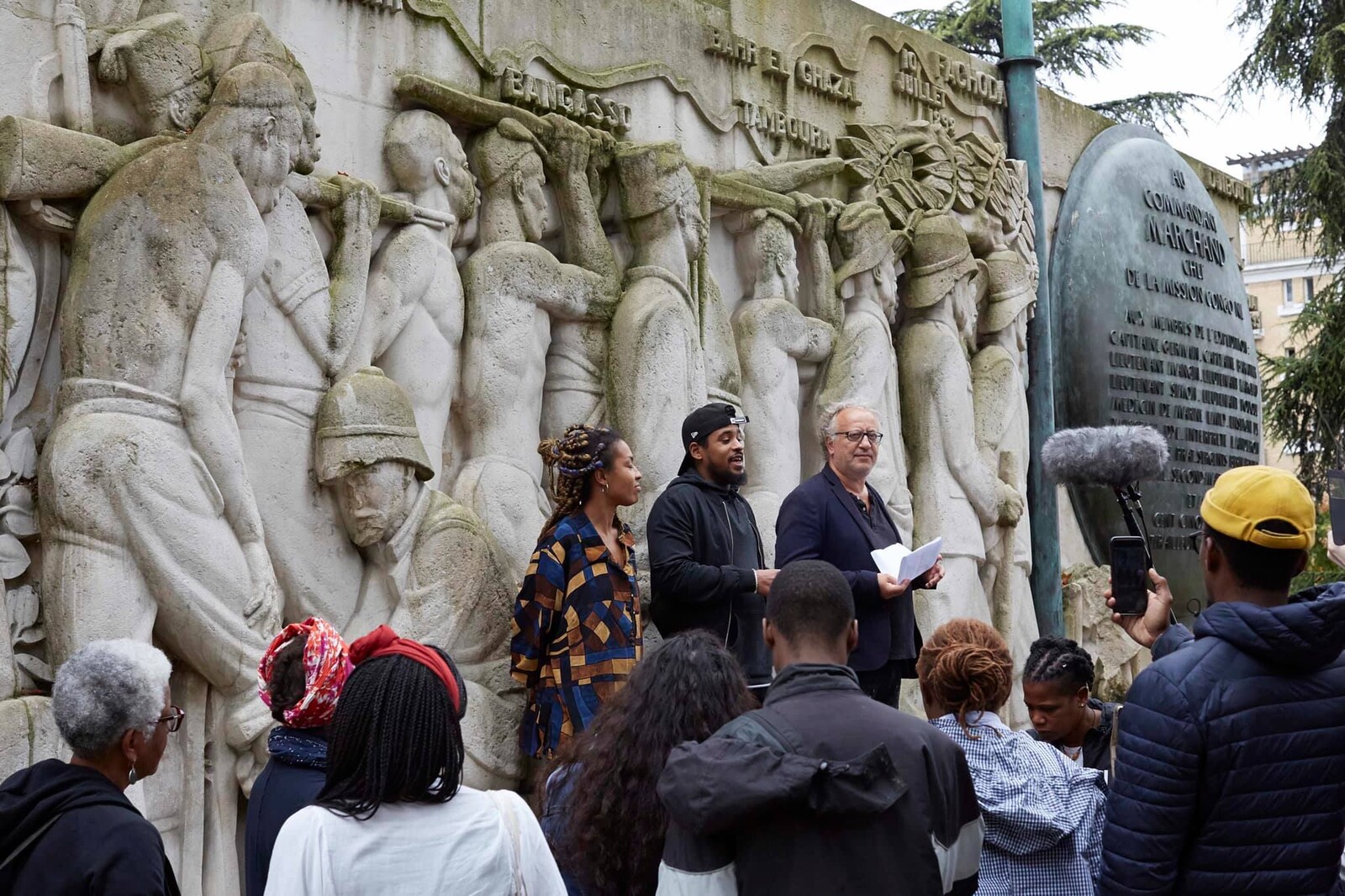

The following text is a compilation of several extracts from the book De la violence coloniale dans l’espace public: Visite du triangle de la Porte Dorée (Of Colonial Violence in the Public Space: A visit to the Porte Dorée Triangle), which was originally written at the request of Lydia Amarouche, founding editor of Shed Publishing, and illustrated by Seumboy Vrainom after a decolonial visit to the Porte Dorée “triangle” in Paris organized by the Décoloniser les arts (Decolonize the Arts) collective in September 2019. Composed at one of its points by the statue of France as Athena, at another by the National Immigration History Museum (the former Museum of the Colonies), and, finally, by the monument to Jean-Baptiste Marchand, the colonial officer who led the French expedition from the Congo River to the Nile (1896–1899), this triangle lent itself to the analysis, in one single site, not only of a colonial aesthetic, but also of the reasons that led to the decision to erect monuments to the glory of colonization. Showing that these monumental constructions were inaugurated at times when anticolonial uprisings, revolts, and insurrections were contesting French domination, I suggested that the authorities were seeking not only to invisibilize this opposition, but by choosing a grandiose aesthetic, also turned colonial massacres, dispossessions, and exploitation into mere details. What the public saw was greatness and monumentality, and thus felt proud of this vast colonial empire.

The book also came after the removal of statues celebrating slavers, colonialists, and segregationists, in protest of the murder of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Even though no statue was toppled in France, the reaction was immediately defensive and reactionary, accusing protestors of “wanting to erase history.” In Martinique, a (post) colonial French territory, however, young Martinican independentists destroyed two statues of Victor Schoelcher on May 22, 2020. While rapidly overlooked in the 2020 discussions of statues, this act was nevertheless radically decolonial. May 22 marks the abolition of slavery in Martinique by the enslaved in 1848. Through their own mobilization, they preceded the implementation of the decree abolishing slavery in the French colonies and declared themselves free. By targeting Schoelcher, a French republican abolitionist, the young Martinicans were also signifying that abolition was never totally complete, and that the aftermaths of slavery—racism, exploitation—remain vivacious on their island. Celebrating the enslaved’s central role in the abolition of slavery and highlighting the perpetuation of colonial domination, their act was truly revolutionary. The book thus also showed that these statues and monuments were always the result of political choices that reflected ideological interests, and further justified the colonial and imperialist “civilizing mission.” The result was an aesthetic of military, sexist, and racist domination. “Stone sentinels” of the colonial world, statues guard bourgeois towns and their acutely gendered, and racially and socially segregated public spaces. The book concluded by proposing decolonial actions around these toxic monuments.

Finally, the book is part of a wider reflection on the decolonizal processes in the arts, culture, and museums that I have been working on for several years now. In my latest book, Programme de désordre absolu. Décoloniser le musée (Programme of Absolute Disorder. Decolonize the Museum, 2023), I write that, in my view, the decolonization of the so-called “universal” Western museum is impossible, firstly because an institution cannot be decolonized so long as racial capitalism continues to predominate, and secondly, because decolonization is not just rhetoric nor a diversity policy; it is, as Frantz Fanon put it, a program of absolute disorder.

An indefensible Europe1

Aimé Césaire’s 1950 analysis of the “boomerang effect” of slavery and colonialism remains valid today.2 Césaire described the process by which racist colonial ideas inevitably come bouncing back like a boomerang in colonizing societies, pervading mentalities and even progressive and emancipatory ideologies. Before falling victim to Nazism, which represented one such boomerang effect, the poet and anticolonial militant observed that Europeans “were its accomplices… they tolerated that Nazism before it was inflicted on them, that they absolved it, shut their eyes to it, legitimized it, because, until then, it had been applied only to non-European peoples; that they have cultivated that Nazism… they are responsible for it, and that before engulfing the whole edifice of Western, Christian civilization, in its reddened waters, it oozes, seeps, and trickles from every crack.” The crime, Césaire continued, was to have “applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the ‘coolies’ of India, and the ‘n……’ of Africa.”3 Accordingly, waving banners proclaiming European humanism was a lie, Césaire insisted, stating: “And that is the great thing I hold against pseudo-humanism: that for too long it has diminished the rights of man, that its concept of those rights has been—and still is—narrow and fragmentary, incomplete and biased, and all things considered, sordidly racist.”4

Regularly cited by those opposing the decolonization of the public space, neither Césaire nor Frantz Fanon espoused an abstract and universalist humanism. When Fanon wrote: “I am not the slave of the Slavery that dehumanized my ancestors,” he was not attempting to erase the heritage of slavery and its dehumanization; he was refusing, rather, that Europe reduce him to its own construction of Black people.5 Fanon exhorted the colonized to turn their back on Europe, concluding: “We must leave … this Europe where they are never done talking of Man, yet murder men everywhere they find them, at the corner of every one of their own streets, in all the corners of the globe.”6 The humanism that Césaire and Fanon called for is not an imitation nor a repetition of European humanism, for “Humanity is waiting for something from us other than such an imitation, which would be almost an obscene caricature.”7 Like Césaire before him, Fanon understood that “if we wish to reply to the expectations of the people of Europe, it is no good sending them back a reflection, even an ideal reflection, of their society and their thought with which from time to time they feel immeasurably sickened.”8 What is at stake, then, is a new phase of decolonization, in which all must rid themselves of their white masks. This has absolutely nothing to do with victimization.

In the many forms it took throughout 2020, the movement challenging statues is irreversible and that is why it is under attack. It is part of the global challenge to a modernity that shaped the world according to racial and sexist criteria that destroyed cultures, silenced voices, erased knowledge, and pillaged to fill its museums and palaces. It contests the “historic statues” that partook in the colonial writing of history, and which are the idols of an old world at the foot of which the authorities lay wreathes of flowers.

A monument to ephemeral and illusory glory (the Porte Dorée Museum)

Designed by architect Albert Laprade, the Palais de la Porte Dorée, whose construction began in 1928, stands at the entrance to the vast space designed to house the 1931 Colonial Exhibition in Paris.9 Like that of many army officers and experts of his time, the architect’s career took him to and fro between France and the colonies. Laprade proposed to create a “synthesis of contemporary Art Deco style, classical French architecture, and elements freely inspired by the art of the colonies.”10 He drew his inspiration from his travels to Morocco where, at the request of Marshal Lyautey, Resident-General of the protectorate, he worked on the urban planning of the city of Casablanca and the French Protectorate Residence in Rabat. His style was a perfect example of a colonial modernity that hybridized European and non-European references.

The display of riches extracted from the colonies, and the depiction of people bent over working, busy doing a thousand actions destined to enrich France, make up the Palais de la Porte Dorée’s 1,200-square-meter façade. It was realized at a time when many cracks were showing in the colonial empire, and when anticolonial groups in France and Europe were honing their arguments. Far from the peaceful image of worlds laboring to enrich France portrayed on this façade, the French colonial empire was facing turmoil. The 1931 International Colonial Exhibition fabricated an illusion: that of a successful pacification and a working empire. This illusion needed its monument, and that would be this immense palace.

The imposing bas-reliefs are the work of sculptor Alfred Auguste-Janniot. The monumental nature of the palace and its bas-reliefs mirrored that of the exhibition. The government wanted to impress and dazzle the public by offering them a performance of the colonial empire that took them around all its conquered territories. A veritable tour de force, in a day, the public could visit Angkor Vat, Timbuktu, the palaces of Niger, or of the Queen of Madagascar. These monuments of vanquished civilizations—now “French possessions”—proved that access to fabulous riches had been secured.

The 1931 Exhibition glorified the French colonial “civilizing mission,” but behind this euphemism were assimilation policies based on dispossession, the Code de l’indigénat (Indigenous Code), which legalized various forms of discrimination in the colonies, forced labor, and exploitation. In 1931, Albert Sarraut, a theoretician, deputy of the Radical-Socialist parliamentary group, and a fervent colonialist, clearly expressed what colonization was: “Let us not obfuscate, let us not pretend. What is the point of disguising reality? Colonization was not originally an act of colonization, a desire for colonization. It is an act of force, of self-interested force.”11 And that is why, he added, in reference to the exhibition, “The Exhibition must be the living apotheosis of France’s overseas expansion under the Third Republic, and the colonial effort of the civilized nations, driven by a same ideal of progress and humanity.”12

The colonial empire: both monumental and fragile

In the colonial empires, which brought not peace nor civilization but massacres and ruin, anticolonial struggles were intensifying. The colossal aspect of the exhibition only fleetingly masked these fissures. It might even be suggested that the exhibition was a gesture destined to obfuscate the colonizing nation’s awareness of the loss that was looming on the horizon, to allay suspicions that the massive military effort needed to quell these revolts and insurrections was in fact in vain given these populations’ irresistible aspiration to freedom and equality.13 By its very inordinateness, the Colonial Exhibition—just like all those that sought to represent the world in its totality—inadvertently revealed the illusion that underlay the colonial project.

The opulence displayed dissimulated the systematic depopulating of the African continent, firstly due to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, then continued during French colonization. Between 1900 and 1921, the population of Equatorial French Africa fell from fifteen million to three million. To complete the Douala-Yaoundé railway line in Cameroon, thousands of workers were brutally deported and forced to work fifty-four hours a week. In 1925, the death rate on this worksite stood at 61.7%, and there was an estimated total of 17,000 deaths.14 Or, as journalist Albert Londres put it, “one Black man per crosstie.” In other words, one African died “for every crosstie” of the 140-kilometer-long Congo-Ocean Railway.

Marshal Lyautey, Resident-General of Morocco, was the chief commissioner of the mammoth works undertaken in Paris. For months, construction workers, artists, fine arts students, sculptors, and other tradesmen worked to realize a dazzling mise-en-scène of colonization on the 110-hectare site. The commissioners clearly hoped that this pacified and welcoming representation of a vast world on a single site would attract the public. They were not mistaken; millions visited the exhibition.

Multiform colonial resistance

It is often claimed that there was no organized anticolonialism or anti-imperialism before the 1940s–1950s. But we recognize the first moment voices spoke out, the first moment revolts were organized as the premises of the independence movements to come. For we decolonial thinkers and activists, people who fought and resisted colonization from the outset have always been anticolonialist. Theories developed by historians of the Subaltern Studies Group, who detected anticolonial enunciations in the songs of the peasant farmer revolts, and who questioned the narrative that only retained the names of bourgeois nationalist leaders, offer us possibilities here to revive these narratives and to question the silence imposed on the subalternized and on women.15

Whatever their form of expression, the resistance discourses and actions of the colonized are part of the vast anticolonial library. Anticolonialism was not born when certain Europeans finally denounced colonialism. In Europe and France in the 1910s to 1920s, Black, Asian, and Arab people organized, wrote, and mobilized. Examples include the Pan-African Congress in Paris in 1919; the creation of the Pan-African Association in 1921; or the LUDRN (Universal League for the Defense of the Black Race) in 1924. The constituent congress of the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression was held in Brussels in 1927. Close to the Communist movement and the Comintern, it was attended by representatives of the African National Congress, the Etoile Nord-Africaine (North African Star), including Lamine Senghor, Messali Hadj, Albert Einstein, Henri Barbusse, Victor Basch, and Jawaharlal Nehru. In its final declaration, the League associated the revolutionary nationalist movement in the colonies with the proletarian struggle in Europe. In French Guiana in 1928, protests against racism and colonialism led to the indictment of fourteen Guianese, whom a court in Nantes refused to condemn in 1931.16

In the colonies, resistance took multiple forms, including political mobilizations, publications, the creation of movements, newspapers, and artistic and cultural creations. In Madagascar in 1927, two anticolonial newspapers were created: L’Opinion and L’Aurore malgache.17

Let us not forget either the major revolt in Kabylia in 1871; the revolt led by Ataï in 1879 in Kanaky;18 the uprisings in Vietnam in 1908; the insurrection in the Rif led by Abdelkrim el-Khattabi (1921-1926); the 1925 revolt in Syria; or again in Vietnam in 1930. To these revolts may be added the creation of the Club des Jeunes Sénégalais (Senegalese Youth Club) in 1910, and the resistance that mass migration constituted, as thousands of people fled the colonized territories. Mention may also be made of armed resistance to colonial penetration, notably that of Maba Diakhou Ba, who attempted to unify the lands to the north of Gambia; Lat Dior Diop in Cayor; Alboury Ndiaye and Mamadou Lamine Drame in the upper Senegal River Valley and the state of Bondu. Revolts and demonstrations demanding rights broke out throughout the entire French colonial empire, including the 1916 revolt of the Somba of Atakor and the Borgu region, but also the Bariba and the Sahoue of Dahomey, and the Agni of Sanwi; the demonstrations in Abéché (Chad) in 1917; the demonstrations of the people of Gabon and the Middle Congo from 1917 to 1918; those of the people of the regions of Ouham-Pendé, Ouham-Barga, and of the part of Cameroon attributed to France in 1919, which the latter “pacified” by massacring and pillaging; the uprisings in Congo and in Ubangi from 1928 to 1931; the first major anticolonial demonstrations that took place in Madagascar in 1929; rebellions, the same year, in the regions of the Ibenga and the Motaba, then of Liakouala and Chad, the insurrection then spreading to Cameroon and Gabon; and uprisings in the Middle Congo in 1930. The French colonial empire was not the only one to meet resistance, for example, the creation of the May Fourth Movement in China in 1919 and the Indian National Congress in 1920; the armed revolt against British occupation in Iraq in 1920; Omar Al-Mukhtar’s armed revolt against Italian occupation in Libya in the 1920s; the creation of the Wafd anticolonial movement in Egypt, whose central committee was presided by the feminist Huda Sha’arawi as of January 1920.

While history has above all retained the names of men, Ndaté Yalla Mbodj in Senegal and the Dahomean women working in Cameroon who went on strike in 1891 show that women took part in the resistance too.19 The colonial regime marginalized the role of women, excluded them from places of learning, and reinforced the patriarchy. At the same time, it did not hesitate to exploit, animalize, and sexualize them, to legitimize rape, dispossession, and even to requisition pregnant women to build roads, without provision of food or payment.

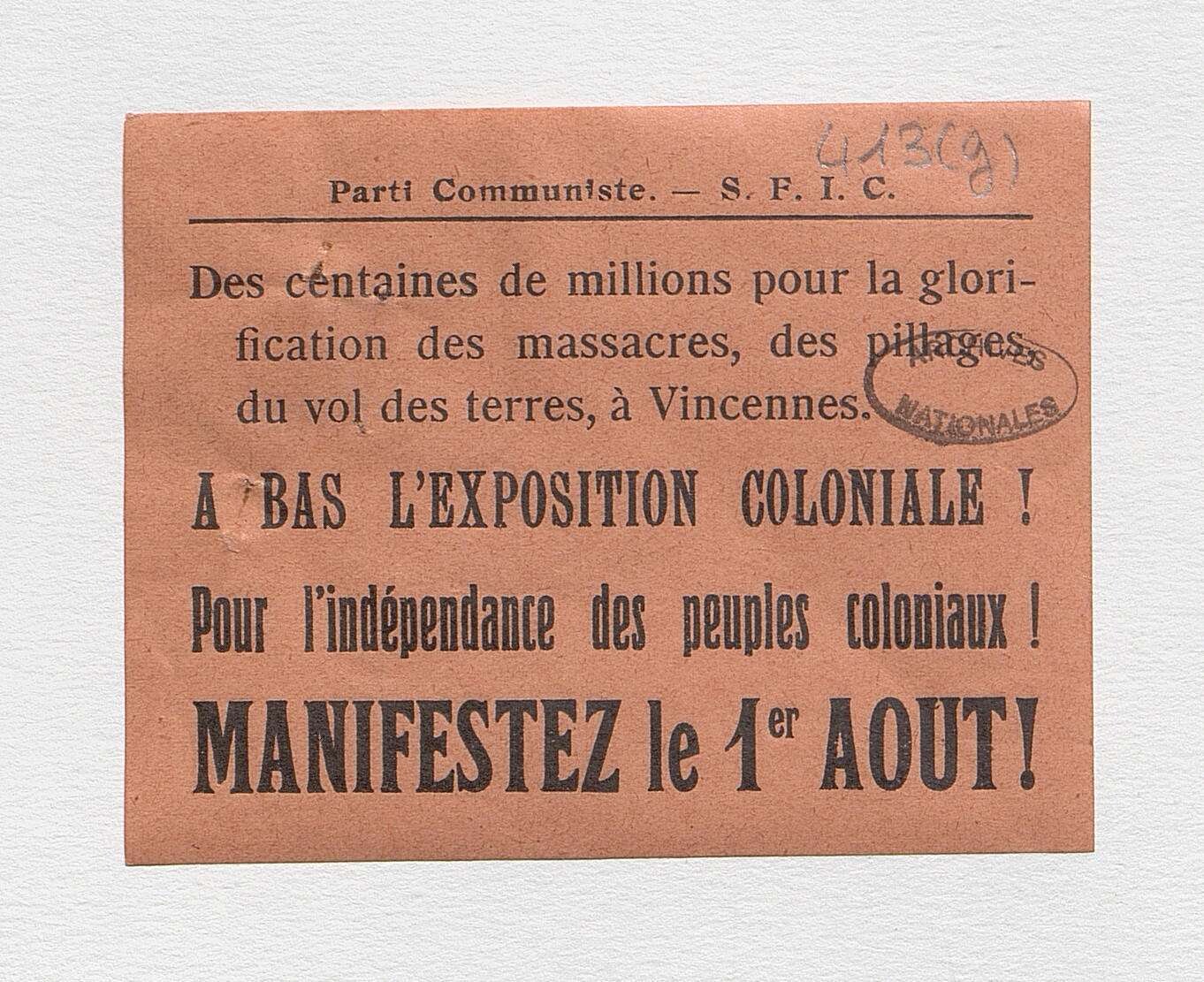

Leaflet distributed by the French Communist Party (PCF). Document collected as part of PCF Monitoring by the Department of National Security of the Ministry of the Interior under the Third Republic, 1931. © Archives nationales (France).

The “apotheosis of a crime”

A vast communications enterprise intended to win French adhesion to racial domination and exploitation, the exhibition appears in light of this resistance to have been a veil thrown over the fragility of colonization, albeit a fragility that few detected yet. When newspapers evoked revolts in the colonies, it was to denounce their “barbaric” nature and to celebrate their crushing. Opinion was far from unanimous, however. Anarchists, Trotskyites, Communists, and certain intellectuals who did not only belong to the far-left signaled the racist and brutal nature of colonization. Students from the colonies created sections within the Union fédérale des étudiants (Federal Students’ Union), where they met left-wing Communist and non-Communist militants. In June 1930, a petition launched in protest at the deportation of Vietnamese and African students arrested on the fringes of May Day demonstrations at the Mur des Fédérés (Communards’ Wall) at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris received many signatures.

In Spring 1931, “the magazine Europe published a petition signed by intellectuals vigorously denouncing the ‘revengeful repression’ carried out by the French government in Indochina, namely the condemnation to death and execution of political prisoners.”20 Every day, the Communist newspaper L’Humanité listed “colonialism’s crimes,” and declared of the 1931 Exhibition: “This is the apotheosis of a crime.”21 Vietnamese people violently opposed to the exhibition printed anticolonial stickers. On May 6, 1931, Surrealists André Breton, Paul Eluard, Tristan Tzara, and Louis Aragon handed out a tract at Vincennes entitled Ne visitez pas l’exposition coloniale (“Don’t Visit the Colonial Exhibition”). With the Communists, they organized a counter-exhibition at Place du Combat (today’s Place du Colonel-Fabien).22 Just 5,000 people visited it, whereas millions of people visited the Colonial Exhibition. Anticolonialism was thereby assimilated with the communist threat, and presented as anti-French and separatist. Repression against anticolonialism intensified at the very moment that Fascism and Nazism were growing in Europe and anti-Semitism was openly expressed in France, and virulently so. The Spanish Civil War was about to break out, in which colonized peoples fought with Republicans against the Fascists, then Nazi and Fascist regimes would come to power in Europe and in Asia.

Adherence to colonialism stemmed from the narcissistic sentiment of belonging to a “great France,” which supposedly brought civilization to populations considered to still be living in barbarity. It was based on racism and on access to the products of colonization. It was, moreover, the partisans of colonization who attacked North African immigrant workers in France.

A racialized depiction of the world

As an institution, the museum partook in the invention of homogeneous, racialized categories (“Africans,” “Asians,” “Arabs,” “Europeans”) that reinforced Western white supremacy and a conception of art and culture that placed Europe at the center of the world.23 By proliferating animalized, sexualized, and racialized representations of “Others,” of which we are not totally rid yet, the museum played a central role in this enterprise.

In his book on nationalism, historian Benedict Anderson describes the museum, along with censuses and maps, as one of the most powerful instruments of codification that created a social world.24 The museum is indeed never a neutral space. The way in which its museography is organized, its architecture, the texts that accompany its objects, the very term “object,” the origin and organization of its collections, all warrant critical reflection. It does not matter whether we go to museums or not, just as it does not matter whether we pay no attention to the statues and monuments we pass as we walk through the town. Their presence conveys a discourse, a way of representing the world.

At the apex, the goddess of war

At the apex of the colonial triangle when it previously stood at the top of the Palace’s steps, the statue of France as the goddess Athena now stands Place Édouard-Renard. The statue represents “France bringing peace and prosperity to the colonies.” Born in Oran, Algeria, Édouard-Renard was the Governor-General of French Equatorial Africa, Prefect of Constantine, then of the Seine. The central median on which the statue is erected was renamed the Square des Anciens-Combattants d’Indochine (Indochina War Veterans Square) in 1987. Three names, three symbols—a concentrate of colonial history, indeed.

A stone tapestry to the glory of extraction

The Palais de la Porte Dorée’s multiple bas-reliefs—or rather, the bas-relief, as they all represent one same theme, namely the exploitation of colonial labor—form a veritable “stone tapestry” and an imposing fresco of imperialist power. The work of sculptor Alfred Auguste Janniot (1889–1969), it constitutes a colonial encyclopedia.25 Entitled: “L’Apport des territoires d’outre-mer à la mère patrie et à la civilization” (“The Overseas Territories’ Contribution to the Motherland and to Civilization”), it is the only of its kind in France in terms of size. In this bas-relief, a vast, diverse, and complex world is reduced to a flat surface on which these figures’ labor contributes to the greatness of France. Of it, Claire Maingon writes: “Magnificently executed by Alfred Auguste Janniot, the vast stone fresco that covers the façade also delivers a message that is both pedagogical and propagandistic. Like a big picture book representing the colonies, the décor illustrates the Empire’s contributions to the metropolis. In it, the colonized ethnic groups are shown in minute detail, and inscriptions help more clearly identify the products and the regions represented.”[figure Claire Maingon, ibid.]

To realize the Black bodies, Alfred Auguste Janniot used live models, as the photo of a Black woman posing naked in his studio attests. For the other characters and plants, he most probably took inspiration from the photographs and drawings brought back by scientists, botanists, ethnographers, soldiers, and administrators. The stone sculptures from the Islamic world, the Indian sub-continent, the Americas, Asia (south-east and east), and the Pacific, which colonizers pillaged or purchased and brought back to France, offered other sources. The Louvre and the Paris Ecole des Beaux-Arts provided French artists with a vast collection of non-European arts, from which they took inspiration and appropriated styles.

The colony as disciplinable “Nature”

The profusion of animals, plants, and humans [on the bas-relief] might be imagined to reference Hindu or Khmer temples if one were not aware of the notion Europe had of the non-European world, where everything was considered indistinctly tangled and interlaced. Humans and animals, plants and pirogues intermix and intertwine. Here, half a body emerges from the foliage; there a child perched on a woman’s hip hovers over a cactus. Further on, the name “Sudan” spills from a lion’s mouth. There is no social life, no towns; the colony is “Nature.”

This disorder contrasts with its orderly finality: the anticipated export of products to France. But it is also a disorder that evokes the ordering of the world through colonization.26 Ethnology, botany, and geography were indeed tasked with organizing this indistinction, with creating categories, themselves classed according to hierarchies. The colony was a huge enterprise in taming fauna, flora, humans, rivers, forests, and mountains. Nothing was to escape the colonizers’ eye, or control. Everything had to be renamed, ordained, arranged, distinguished according to norms that reinforced an epistemology and imposed rigid binarities on worlds that had complex understandings of the living. Colonization was a project of control, possession, and transparency.

Thanks to this bas-relief, the French were given the impression of knowing everything about a world laying at its fingertips, that colonization offered them the entire diversity of the world, pacified, disciplined, subjected. Humans, plants, and animals were part of a same ensemble, a wild animal world tamed for Europe’s pleasure, comfort, and well-being. The exhibition’s Jardin d’Acclimatation was an instrument of this organization; the public could imagine it was visiting the jungle, the savannah, tropical forests, and seas comfortably and safely. The aquarium in the museum’s basement was thus not an error of conception; it accredited the idea of an appeased and tamed ensemble. This ordering of the world was, then, more than a matter of images and discourse.

An ode to exploitation

When facing the Palais de la Porte Dorée, the African colonies can be seen represented to the left, and the Asian colonies to the right. The colonies of the Caribbean, Americas, and Indian Ocean are situated on the left side of the building, and those of the Pacific on the right side. Above the central main entrance, France appears in the image of a seated woman, her breast bared, surrounded by signs of fecundity and opulence, flowers and fruit, a cow, a bull, and horse heads. At her feet are two Roman goddesses: Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, and Pomona, goddess of fruit trees. It is beneath these clearly gendered symbols and accompanied by the motto “Paix et Liberté” (“Peace and Liberty”) that the public enters the museum.

Right next to the figure of France, planes and ships indicate her command of the seas and air. European ships alone are associated with this command; other peoples only have pirogues. That exceptionally talented seafarers had navigated the Pacific and Indian Oceans for thousands of years, and that European navigation drew from their knowledge (compasses, understanding currents, the use of local pilots), none of these elements had their place in a representation of the civilizing mission.

Decolonize public space

What should replace these statues and monuments? Do we want more of them? Do we want to saturate the city with more stone, bronze, and metal mausoleums, or to think of new forms? Coming up with ideas, however fanciful, is a necessary first step. We have the right to imagine. Replace [Marshall] Gallieni’s statue with trees; why not?27 Create a memory garden in the place of the monument to Marchand; why not? Create an opaque screen in front of this monument, on which other facts, other names appear; why not? Or what about removing them all together?

Decolonizing public space also means putting a stop to racial profiling, to the fabrication of bodies that can be killed, to hikes in public transport costs, to architecture that is hostile to disabled people, to the sexual, racial, cultural, and social segregation of public space, to the invisiblization and thus exclusion of key workers—cleaning staff, cashiers, garbage collectors—but also of sex workers, refugees, migrants, homeless people, old people, women. It means humanizing the city.28

The power of imagining

We are conscious of our own part in the decolonization process. We also see the extent to which structures of racism destroy the possibility of living differently, that they straight-jacket the imagination, that they stifle us, that they sever ties, divide, whip up acrimony and hatred. We closely observe our environment and do not content ourselves with just contesting it. We do not want to obey a patrimonial law either, which rigidifies history and heritage. We want to retrace the cartographies of transnational and transcontinental resistance, to give voice to the narratives of emerging communities, to encourage exchange and debate. We no longer want to be put under house arrest, confined. We no longer want cities segregated by class, gender, sexualities, race, trapped in narratives that do not reflect the plurality of their lives, devoid of emotions, turned into the empty settings for ads. We want to decolonize our cities.

The term is borrowed from Aimé Césaire, who, in Discourse On Colonialism, (1950), wrote: “The fact is that the so-called European civilization – ‘Western’ civilization – as it has been shaped by two centuries of bourgeois rule, is incapable of solving the two major problems to which its existence has given rise; that Europe is unable to justify itself either before the bar of ‘reason’ or before the bar of ‘conscience’; and that, increasingly, it takes refuge in a hypocrisy which is all the more odious because it is less and less likely to deceive. Europe is indefensible.” Trans. Joan Pinkham (NY: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 31-32.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 36.

Ibid, 37.

Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (London: Pluto Press, 1986), 230.

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (NY: Grove Weidenfeld, 1963), 311.

Ibid, 315.

Ibid, 316.

On Albert Laprade, see: Albert Laprade, Les carnets d’architecture d’Albert Laprade (Paris: Kubik Editions, 2008); Maurice Culot & Anne Lambrichs, Albert Laprade (1883-1978) (Paris: Editions Norma, 2007); Anne Demeurisse, ed., Alfred-Auguste Janniot (1889-1969), (Paris: Editions Somogy, 2003). On the building, see: Hélène Bocard, Le palais de la Porte Dorée (Paris : Editions du Patrimoine, Collection(s) : Itinéraires du patrimoine, 2018); Maureen Murphy, Un Palais pour une Cité. Du musée des colonies à la Cité de l’histoire de l’immigration (Paris: RMN-CNHI, 2007); and Germain Viatte, ed., Le Palais des colonies, Histoire du Musée des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie (Paris: Editions RMN, 2002). On the bas-relief, see: Georges Petit, “La faune exotique dans les bas-reliefs du musée des Colonies”, La Terre et la vie. Revue d’histoire naturelle, 1. (February, 1931). On the colonial exhibitions, see: Charles-Robert Ageron, “L’exposition coloniale de 1931 : mythe républicain ou mythe impérial”, in Pierre Nora, ed., Les Lieux de mémoires, 1, La République (Paris: Gallimard, 1984); Catherine Hodeir & Michel Pierre, L’Exposition coloniale de 1931 (Brussels: Complexe, 1991).

National Immigration History Museum website and Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, ed., Guide du Patrimoine Paris (Paris: Hachette, 1994).

Cited by Gilles Manceron, Marianne et les colonies. Une introduction à l’histoire coloniale de la France (Paris: La Découverte, 2003), 153.

Cited by Charles-Robert Ageron, “Les colonies devant l’opinion publique française (1919-1939),” Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer, tome 77, 286. (1er trimestre 1990), 51.

Clair Maingon, “Le palais de la Porte-Dorée, témoignage de l’histoire coloniale”, Histoire par l’image (April 2008), https://histoire-image.org/etudes/palais-porte-doree-temoignage-histoire-coloniale; Steve Ungar, “La France impériale exposée en 1931 : une apothéose”, Sandrine Lemaire, ed., Culture coloniale 1871-1931. (Paris : Autrement, 2003), 201-211; Raoul Girardet, “L’apothéose de la ‘plus grande France’: l’idée coloniale devant l’opinion française (1930-1935)”, Revue française de science politique, 18ᵉ année, 6. (1968), 1085-1114.

See: Roland Pourtier, “Les chemins de fer en Afrique subsaharienne, entre passé révolu et recompositions incertaines”, Belgeo, 2. (2007), 189-202; Owona Adalbert. “A l’aube du nationalisme camerounais : la curieuse figure de Vincent Ganty”, Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer, tome 56, 204. (3e trimestre, 1969), 199-235.

On postcoloniality, see notably: Thomas Brisson, “Les ‘études subalternes’ indiennes et le ‘tournant saidien’”, Brisson, ed., Décentrer l’Occident. Les intellectuels postcoloniaux chinois, indiens et arabes, et la critique de la modernité (Paris: La Découverte, 2018) 215-271; Neil Lazarus, ed., Penser le postcolonial : une introduction critique (Paris: Editions Amsterdam, 2006); Capucine Boidin, “Études décoloniales et postcoloniales dans les débats français”, Cahiers des Amériques latines, 62. (2009), 129-140; Mamadou Diouf, L’historiographie indienne en débat, colonialisme, nationalisme et sociétés postcoloniales (Paris: Karthala, 1999); Achille Mbembe, De la postcolonie. Essai sur l’imagination politique dans l’Afrique contemporaine (Paris: Karthala, 2000); Mbembe, “Postcolonial et politique de l’histoire”, Multitudes, 26. (Sept. 2006); Jim Cohen, Elsa Dorlin, Dimitri Nicolaïdis, Malika Rahal & Patrick Simon, eds., “Qui a peur du postcolonial?”, Mouvements, 51. (Sept.-Oct. 2007); Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” Wedge, 1985.

There are many publications on anticolonial struggles, and increasingly so. It is impossible to do them justice without citing them all.

See, among others: the indispensable Amzat Boukari-Yabara, Africa Unite ! Une histoire du panafricanisme (Paris: La Découverte, 2014); the useful reference, despite its oversights, Philippe Dewitte, Les mouvements nègres en France, 1919-1939 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1985); François Manchuelle, “Le rôle des Antillais dans l’apparition du nationalisme culturel en Afrique noire francophone”, Cahiers d’études africaines, vol. 32, 127. (1992), 375-408; Fredrik Petersson, “La Ligue anti-impérialiste : un espace transnational restreint, 1927-1937”, monde(s). (Nov., 2016), 129-150. See also: in Histoire générale de l’Afrique VII, UNESCO (2000): M’Baye Gueye & Albert Adu Boahen, “Initiatives et résistances africaines en Afrique occidentales de 1880 à 1914”, 137-170; Walter Rodney, “L’économie coloniale”, pp. 361-380; Albert Adu Boahen, “La politique et le nationalisme en Afrique occidentale, 1915-1935”, 669.

The Kanak leader Ataï was decapitated, and his head sent to Natural History Museum in Paris in the aim of confirming the inferiority of the Kanaks, then was forgotten in the museum’s reserves. In the twentieth century, the Kanak people requested that Ataï’s skull be returned. After long negotiations with the French State and the museum, which could not “find” the skull, Ataï was finally returned to his people in 2014. A very powerful vast ceremony of return was celebrated in his honor.

Fatou Sarr, “Féminismes en Afrique occidentale ? Prise de conscience et luttes politiques et sociales”, Vents d’Est, vents d’Ouest : Mouvements de femmes et féminismes anticoloniaux (Graduate Institute Publications, 2009). See also: Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, “Femmes et politique : résistance et action en Afrique de l’Ouest”, in Coquery-Vidrovitch, Les Africaines. Histoire des femmes d’Afrique subsaharienne du XIXe au XXe siècle (Paris: La Découverte, 2013), 253-288. Also see: Cheikh-Anta Diop, Nations nègres et culture (Paris: Présence africaine, 2000); Joseph Ki Zerbo, Histoire de l’Afrique noire (Paris: Hatier, 1994); Histoire générale de l’Afrique, volume 1, Afrique & histoire, “L’anticolonialisme (cinquante ans après). Autour du Livre noir du colonialisme” (Paris: UNESCO, 2003), 245-267. Then see: Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, “L’Afrique coloniale française et la crise de 1930 : crise structurelle et genèse du Rapport d’ensemble”, Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer, tome 63, 232-233. (3e et 4e trimestres, 1976); Coquery-Vidrovitch, ed., L’Afrique et la crise de 1930 (1924-1938), 386-424; Didier Monciaud, “Rebelles contre l’ordre colonial : expériences et trajectoires historiques de résistances anticoloniales”, Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’histoire critique, 126. (2015), 13-18; Alain Gresh, “Révoltes prémonitoires dans les colonies”, Le Monde diplomatique. (Sept. 2014), 46-47; Bernard Lanne. “Résistances et mouvements anticoloniaux au Tchad (1914-1940)”, Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer, tome 80, 300. (3e trimestre, 1993), 425-442.

Pierre-Frédéric Charpentier, “Imbéciles, c’est pour vous que je meurs”. Valentin Feldman (1909-1942) (Paris: CNRS Editions, 2021), 87 & 88.

Cited by Raoul Girardet, “L’apothéose de la ‘plus grande France’ : l’idée coloniale devant l’opinion française (1930-1935)”, Revue française de science politique, 6. (1968), 1085-1114. Also see: Charles-Robert Ageron, “Les colonies devant l’opinion publique française (1919-1939)”, Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer, tome 77, 286. (1st trimester, 1990), 31-73. The author fittingly describes the huge propaganda effort that the government undertook, with the help of learned societies and the media, to popularize the colonial empire among the French.

On July 4, 1931, L’Humanité announced a counter-exhibition. Entitled La vérité sur les colonies (The Truth About the Colonies), it was organized by the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression and was set up in a large, two-story wooden construction with vast bay windows on a piece of land belonging to the CGTU (United General Confederation of Labor), Place du Colonel Fabien in Paris. See: Alain Ruscio, “Contre l’Exposition coloniale de 1931 (Paris-Vincennes) : des voix fermes, mais bien isolées. Aperçus”, Aden, vol. 8, 1. (2009), 104-111; Vincent Bollenot, “‘Ne visitez pas l’exposition coloniale!’ La campagne contre l’exposition coloniale internationale de 1931, un moment anti-impérialiste”, French Colonial History, 18. (2019), 69-100.

A lot of works exist concerning the decolonization of the museum, starting with its very possibility.

Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, (London & NY: Verso, 1983), chapter 10. Studies of the museum as a structural element of nationalism and colonialism have multiplied these past decades, testifying to the importance of this institution in the invention of a tradition, the Eurocentric presentation of the world, and civilizing racism. It is difficult to choose from this abundant bibliography, but mention must undoubtedly be made of the seminal work by Edward Said, Orientalism. Western Conceptions of the Orient (London: Routledge, 1978). In recent years, museums have begun revising their museography and labels, but in the eyes of researchers, artists, and decolonial activists, this revision has not radically challenged structures. See, for example: Fisun Güner, “Why Decolonizing Museums Is Not Enough”, Elephant Magazine (10 December 2020), ➝, or Arwa Aburawa’s film The Museum Will Not Be Decolonized (2019), ➝.

A specialist of monumental stone décors, a prolific sculptor of numerous public commissions, Alfred-Auguste Janniot marked the history of Art Déco. He also realized the bas-reliefs of the Rockefeller Center in New York in 1934, those of the Bordeaux Labor Exchange in 1936, two of the major bas-reliefs on the back of the Palais de Tokyo in Paris for the 1937 Universal Exhibition, and the high reliefs of the Mont-Valérien Memorial in 1956. Claire Maingon, Alfred Janniot (1889-1969) : à la gloire de Nice (Paris: Galerie, Michel Giraud, 2007); Anne Demeurisse, ed., Alfred Auguste Janniot - 1889-1969 (Paris: Éditions d’Art Somogy, 2003).

On botany’s role in colonization, see: Lucile H. Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion. The Role of the British Royal Botanic (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002); Londa L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empires: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2009); and the book that demonstrates the consequences of pillaging, Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London/NY: Verso, 2018).

Gallieni’s statue stands in Place Vauban in Paris, behind the École Militaire army training facilities. This square and the nearby Place Denys host quite a collection of Marshals – Gallieni, Lyautey, Fayolle – plus one General, Mangin. This is yet another site in Paris that assembles several elements of France’s colonial, racial, and gendered history.

On November 21, 2020, French police beat up the music producer Michel Zecler because he was Black. He was given 180 days’ temporary incapacity to work, “due to the physical repercussions, and the psychological impact signaled by his doctors.” Thanks to videos filmed by neighbors, this beating was made public, and the truth re-established, as, after taking him into custody, the police intended to accuse Zecler of assaulting a police officer.

Appropriations is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and CIVA Brussels within the context of its exhibition “Style Congo: Heritage & Heresy.”

Category

Subject

Translated from the French by Melissa Thackway.

Originally published as part of the book De la violence coloniale dans l’espace public: Visite du triangle de la Porte Dorée (Of Colonial Violence in Public Space: A visit to the Porte Dorée Triangle) (Shed Publishing, 2021).