The Problem of Evidence

Evidence has long been considered one of the greatest challenges for historians of sub-Saharan Africa. Written evidence is the sine qua non of the historical disciplines. Though it is becoming increasingly clear that Africa had many long, rich, and diverse traditions of writing from ancient times to the present that have been largely unacknowledged, most people in Sub-Saharan Africa did not adopt phonetic writing systems until the late nineteenth century. Without easy access to self-produced written documents recording African history, historians have relied on documents written by Arab and European visitors with their attendant problems.1

The problem of evidence is exacerbated when it comes to understanding histories of African material cultures and built environments. In these cases, because material remains and visual representations may be even more important than written evidence. Climatic conditions, choice of materials, and historical cultural practices have meant that many past buildings in Sub-Saharan Africa have not survived to be used as evidence today. In response, scholars of African architecture have adopted ethnographic methods and oral sources, which, of course, bring their own problems.2

There is a need for innovative thinking about evidence in histories of African built environments. One possible avenue is the large number of problematic European written sources on Sub-Saharan Africa from the fifteenth to the nineteenth centuries. By one 1980s account, there were over 700 books and articles on West and West Central Africa published in European languages before 1865. Similar numbers were cited for Southern Africa, but much lower for Central and Eastern Africa for the same timeframe (there is a spatial inconsistency in available sources).3 Ultimately, in quantitative terms, written European sources dwarf both written Arabic sources and collected oral traditions by many magnitudes.

Historians understandably avoid these sources because they are biased: they were largely written by non-African foreigners entrenched in the political and economic conditions and cultural attitudes of their times and places of origin. Exceptions do exist, including letters written by the kings and queens of the Kongo Kingdom and the Kingdom of Angola to their corollaries in Portugal, over a thousand documents written and preserved by chiefly authorities in northern Angola, and letters from kings of the kingdoms of Benin and Dahomey to European leaders and religious authorities, all from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.4 Rather than dismissing biased sources as useless, is it possible to approach them critically and leverage them for the insights they can offer?

Hermann Frobenius on Maasai and Tembe Buildings in East Africa

I am currently translating into English and annotating a series of forgotten late nineteenth-century German-language essays published between 1894–1898 by the retired Prussian military architect Hermann Frobenius.5 There is no evidence so far that Frobenius traveled to the African continent. Rather, his work followed the well-known model of “armchair anthropology” in which observers in Europe tried to understand the diversity of world cultures on the basis of information collected and recorded by missionaries, colonial officers, explorers, and other informants on the ground. Between 1893–1899, in two books and one essay, Frobenius synthesized five centuries of descriptions of African buildings by European explorers: including the fifteenth-century Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, the sixteenth-century Spanish Muslim-Moroccan-Italian traveler Al-Hasan al-Wazzan/Leo Africanus, the seventeenth-century Dutch humanist and armchair explorer Olfert Dapper, and almost the entire slate of eighteenth and nineteenth German, French, and British explorers.

The following excerpt is from the provocatively-named Afrikanische Bautypen—eine etnograpisch-architektonische Studie (African Building Types: An Ethnographic-Architectural Study, 1894). The excerpt is from the book’s third chapter, titled “Buildings with Rectangular Ground Plans,” which is preceded by two chapters arguing that the spherical building on a curvilinear floor plan is the original form of ethnic groups that belong to Bantu language family speakers of southern Africa. Conversely, in this chapter, Frobenius looks at rectilinear forms in parts of East, Central, and coastal West Central Africa, and tries to understand where, when, why, and how the shift from round to rectilinear forms occurred. In the excerpt, he discusses a building form that he associates with the Maasai ethnic group, and argues that it is the basis for the tembe, a type of building which spread across East Africa and was adopted by many ethnic groups as well as by traders who migrated to the East African coast from the Arabian Peninsula starting ca. 750 CE.

Annotated Excerpt from Afrikanische Bautypen by Hermann Frobenius (1894)6

There is no doubt that the Maasai ethnic group brought a building style based on a rectangular ground plan with them from the north, from where they advanced toward the center of East Africa. They inserted themselves like a wedge between Lake Victoria and Mount Kilimanjaro, driving out the indigenous population here, partly turning the locals into Maasai, and directly asserting their influence as far down as Ugogo region.

The “Maasai” are a large ethnic group living in modern Kenya and Tanzania. Their origins are uncertain but one theory suggests that they migrated from the area that is now southern Sudan before 1000 CE. They gradually shifted from agro-pastoralism to a pastoral economy. A series of wars in the nineteenth century made them vulnerable to European colonialism under Britain and Germany. Europeans romanticized aspects of the Maasai way of life, especially their warrior tradition, but derided their communal approach to land and the value they placed on cattle, and dispossessed them.7

“Ethnic group” or “people” has been substituted for “tribe” throughout this translation. The English term “tribe” was used in Judeo-Christian and Roman texts to describe a community descended from a common ancestor. By the nineteenth century, however, this meaning was no longer common. Instead, as a result of the merger of social evolutionism with racial theories, “tribe” was applied primarily to non-white societies. Today, scholars of Africa avoid “tribe” because it has no consistent meaning when applied to African groups of diverse sizes, modes of social organization, and histories. Furthermore, the term suggests that African societies are timeless.8

“Ugogo” is a region in contemporary central Tanzania. It is an arid zone that was historically the home of the Gogo (Wagogo) people.9

Dr. Franz Stuhlmann believes that it is from the Maasai building style that the form of the tembes developed and was transferred to the Nyamwezi ethnic group as well as to the Hehe people, who were pushing forward from the south—probably because it was an excellent way of combining a dwelling with the fortification and protection of the villages. On the other hand, however, the Arabs may also have contributed to developing and further spreading the building form, because they undoubtedly adopted it for their cities, towns, and villages.

Unable to conduct fieldwork in Africa himself, Frobenius draws all of his material from travel narratives published by European explorers between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. “Franz Stuhlmann” (1863-1928) was one such explorer. He was a German colonial administrator and naturalist. Starting in the late 1880s, he travelled in Egypt, Zanzibar, and Mozambique, Tanzania, India, the Dutch East Indies, Algeria, and Tunisia. After serving in the German colonial army, he participated in Emin Pasha’s expedition to the Great Lakes region in the 1890s, from which he brought back thousands of botanical samples to Berlin. Later, he directed a successful agricultural research station in Tanzania (German East Africa) before returning to Hamburg, Germany, to serve at the Colonial Institute. He was well-respected for his publications on botany, geography, and colonial economics. Frobenius draws extensively on Stuhlmann’s Mit Emin Pascha ins Herz von Afrika (1894), including his hypothesis about the origins and spread of buildings styles and types in East Africa.10

“Tembe” is an old Swahili word describing a house made of earth whose roof is integrated into rather than independent of its walls. The term is no longer in common parlance.11 Nineteenth-century German anthropologists defined the tembe as follows: “a building and settlement form disseminated widely across East Africa. The simplest tembe is a house about 2 m high, up to 3 m deep and of various lengths, in the form of a covered wagon, with a slightly arched or sloping roof. The walls consist of a network of rammed-in stakes, poles, rods and branches with clay plaster outside and inside.”12 A late twentieth-century ethnographic study reported the continuation of “traditional” building forms in the Unyamwezi region in west central Tanzania mentions rectangular houses with flat roofs (itembe) or thatched gable roofs much like Frobenius described.13

Today, the “Nyamwezi” are the largest ethnic group in Tanzania. “Nyamwezi” first appeared in written European records in the nineteenth century. It is possible therefore that the Nyamwezi were a group designated by others rather than an organic ethnic group. From their base on the coast of today’s Tanzania, Nyamwezi people dominated trade inland, which brought them wealth and status. They supplied ivory, copper, wax, and enslaved people to coastal Arab-Swahili traders, and later became agents of the German and British colonial governments.14

An ethnic group who have occupied the south-central region of contemporary Tanzania at least since the arrival of Europeans, “Hehe” society was disrupted by the arrival of the Ngoni people from South Africa in the 1830s. They adopted Ngoni military techniques and unified into a single state in the 1860s. By the 1880s, Hehe was one of the two most powerful states in southern Tanzania until the imposition of German rule. They vehemently resisted German rule until they were defeated in the late 1890s.15

Frobenius is referring here to the people who arrived on the East African coast from the Arabian Peninsula and Persia via the Indian Ocean as early as 750 CE. It was long believed that these people—who self-identified as “Arabs”—established the large city-states that line the East African coast and associated dynamic cultural identity of the region. Today, we know that the movement of people from Asia to the east coast of Africa has been ongoing and complex. These migrants mixed with Bantu language family speakers who had migrated to the region even earlier from areas now in Kenya and Somalia, and founded coastal towns. Together, the two groups created the unique Swahili culture and language. Furthermore, as several scholars have explained, “Arab” has long been a complex marker of identity in the region—one that does not map on readily to simplistic assumptions about skin color or genealogy.16

The stately stone architecture of East African cities and towns such as Mombasa and Bagamoyo was long considered evidence that Arab culture assimilated local African cultures. Thus, Frobenius’s suggestion that “Arabs” adopted and spread the existing tembe “building style” is a rare nineteenth-century European acknowledgement that East African ethnic groups were important participants in the emerging Swahili culture and society. This nineteenth-century European bias has, until recently, defined much of what we know about East African architecture. Archaeological and art historical research offers a different picture today.17

Through much of the text, Frobenius refers to African “settlements” or “locations.” These terms signal the fraught Western interpretation of the history of urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa, where African urban forms were first seen as inconceivable and later understood as other or lesser than their Western counterparts because they did not follow the Western Mediterranean model in which cities are defined not only by their size but also by the simultaneous emergence of writing, construction of public works, cohabitation of heterogeneous populations, and other supposedly universal characteristics. Thus, terms like “settlement,” “village,” “camp,” “compound,” and “homestead” were long used in place of “city” or “town.” The refusal to recognize the continent’s urban past is still present in some scholarship and in media and popular narratives today. When the particular nature of settlement is unclear, I use “city, town, or village.”18

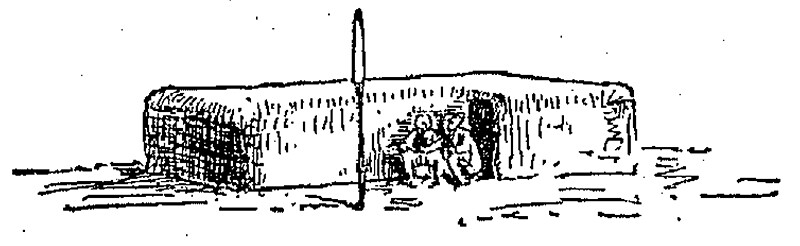

Dr. Franz Stuhlmann describes a Maasai home that he regards as the ur type of the tembe (fig. 38a) as follows:

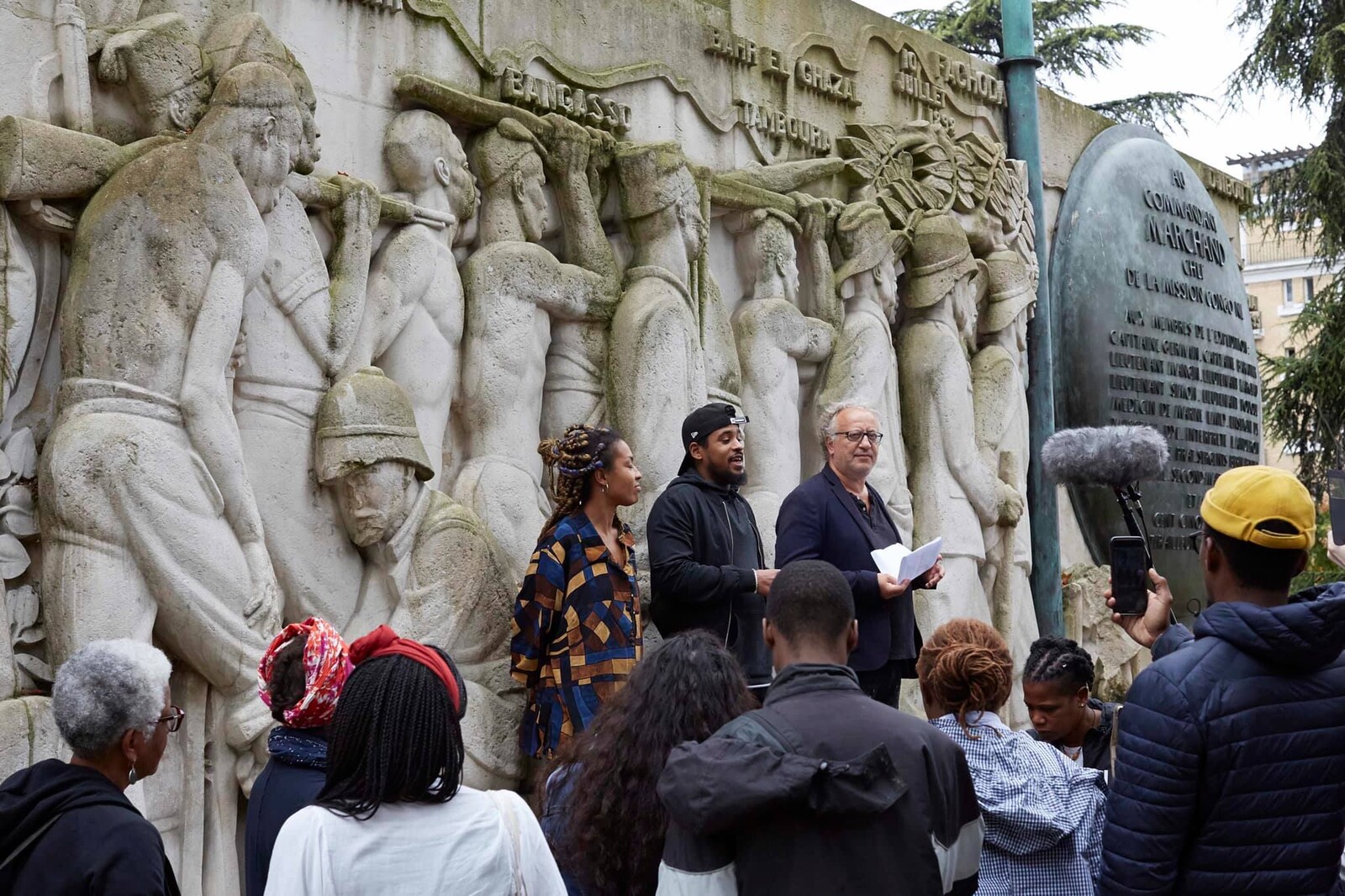

Fig. 38a: A Maasai House. This and the majority of Frobenius’s illustrations are redrawings of images from his sources. In these sources, illustrations were provided by a small but well-established cadre of colonial artists who either worked with sketches provided by explorers or participated in expeditions themselves. Frobenius often altered these images in order to meet his own agenda—usually by omitting contextual information or correcting what he perceived to be inaccurate based on his architectural expertise. Frobenius cites Stuhlmann as the source of the specific image of a Maasai building depicted here, and it is indeed based a drawing in Stuhlmann, Mit Emin Pascha (Figure 263, 812). But Frobenius elongated the original sketch created by the German colonial artist, Wilhelm Kuhnert, and eliminated one of the two spears depicted in front of the building and the foliage shown behind it. Lastly, the detailed human figures in front of Kuhnert’s building blend into the background in Frobenius’ version. Frobenius also often simplified captions in his sources in order to emphasize what he believed was the ethnic affiliation of a particular building form, though that is not the case here.

On one side of the courtyard were four buildings with a basic rectangular shape. They were about 1 m high, 6-8 m long, and 4 m wide. The entrance was sideways, in the projecting structure on the longitudinal side, approximately like the opening in a snail shell. In the interior, near the entrance, was the hearth. In the main room, brushwood had been spread along the sides on which the warriors could sleep. With its flat vaulted roof, the building gave the impression of a barrel—all the edges were rounded. The framework of the building, which was made of brushwood, was sealed with clay and cow manure.19

This sentence reveals the underlying purpose of the text—to identify the primordial (“ur”) building type from which the tembe developed, reconstruct the development of spinoff forms, and correlate these forms with culture and geography. This analysis, then, is Frobenius’s effort to prove Kulturkreis (culture complex) theory, the dominant anthropological theory of late nineteenth-century western Europe. Friedrich Ratzel is believed to have coined the term “Kulturkreis” but Hermann Frobenius’s son, Leo Frobenius, popularized it. Leo Frobenius argued that all parts of a culture including the social, mythological, and material, make an organic whole that migrates with people. Frobenius and other anthropologists believed that it was therefore possible to understand the historical relationships between peoples across time and space by identifying and analyzing Kulturkreise. Hermann Frobenius’s Afrikanisch Bautypen provides evidence that he was thinking about this topic before his son first published on it in 1898.20

I use “building” in place of “hut” throughout this text. Like “tribe,” today “hut” is only used in reference to buildings outside of the Western world. Since at least the nineteenth century, “hut” was used by European observers to describe a building type they saw as a diminutive and inferior to “house” or “building.” Drawing on postcolonial theory, we can say that a “hut” was the same but “not quite” as European buildings, and this distinction served to police cultural and racial boundaries.

Frobenius’s use of an analogy (“like the opening in a snail shell”) between an African architectural form and a biological form was not unusual. He compares other African buildings to termite mounds and beehives. The trope of nature-as-model appears in other nineteenth-century European writing on African architecture such as an 1840s report by a member of the Basel Missionary Society.21 The use of organic analogies continued in the twentieth century, but they were now supported by ethnographic documentation such as the work of Marcel Griaule on the historical houses of Dogon people in Mali.22 These organic analogies are both helpful and problematic. On one hand they recognize the existence of other spatial epistemologies. On the other hand, they lend support to theories of incommensurable difference between African and European experiences.

The tembe is probably originally nothing more than a rectangular, elongated building with a flat roof and sealed with clay. In all likelihood several of them were placed around the stockyard and finally completely connected with one another so as to provide the necessary protection. Perhaps, because of the violent winds, the buildings were half sunk in the ground.23

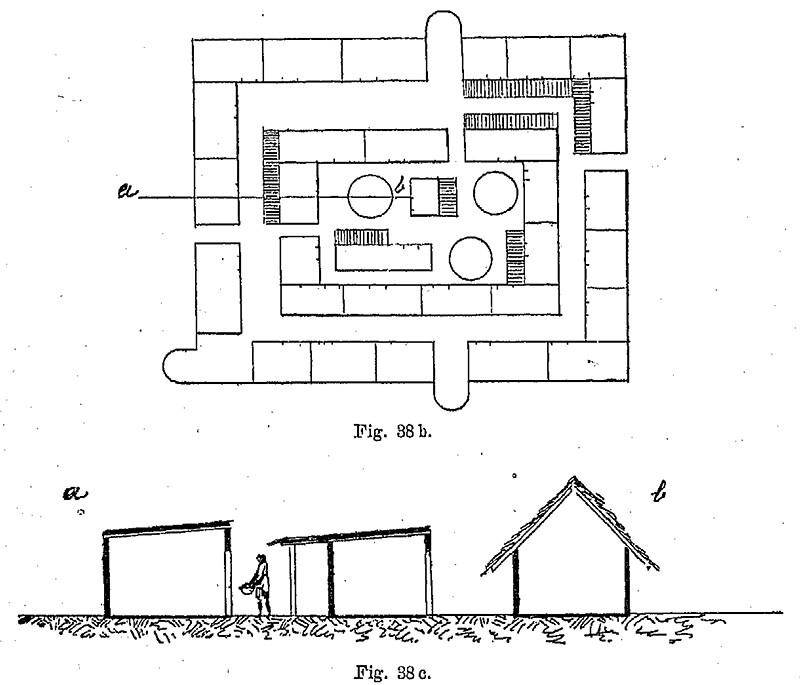

Fig. 38b: Plan and cross-section of Tembe, Wagogo ethnic group (after Franz Stuhlmann).

Rewriting Hermann Frobenius’s History of African Architecture

Taking into account the need for evidence in histories of African built environments, how should we approach translating Frobenius? The first step is to understand that the text has even less basis in reality than many evidentiary documents. As anthropologist Beatrix Heintze has explained, at the time of their production, written sources on Africa were alienated physically and cognitively from the realities they wished to represent and they are therefore more properly understood as translations of situations, events, and processes.24 Hermann Frobenius himself read and translated (sometimes verbatim) a large number of these written sources in other European languages. Today’s readers are also alienated from texts like Frobenius’s in at least four ways: by time, by culture, by space, and by language. To translate Frobenius today is therefore to translate a text that has undergone at least four degrees of translation. Unlike Africanist scholars wary of adding another obscuring layer to already “corrupted” information in written sources, I would argue that acknowledging the disconnect between signifier (Frobenius’s words) and signified (“reality” or historical experiences of Africans) in these European texts on Africa (i.e. acknowledging the impossibility of translation) frees us from the tyranny of literal interlingual translation.25

Scholars typically agonize over the Eurocentrism of texts like Afrikanische Bautypen, which are often rife with pejorative language and factual inaccuracies. How does one approach translation taking into account the responsibility of neither perpetuating nor perpetrating epistemic and structural violence across generations? How does a translator who is an insider-outsider to both the source and target cultures and texts navigate her task? My method is grounded in postcolonial and decolonial approaches that approach translation as: 1) a metaphor for intercultural encounter, 2) an actual linguistic practice involving intercultural mediation often shaped by asymmetrical power relations, and 3) a creative act that can be reclaimed in an effort to destabilize power and ideology. Translation becomes (to borrow some concepts from translation theorists) “rewriting,” “new writing,” “retranslation,” “back translation,” “recreation,” anthropophagia, or even an act of “critical fabulation.”26

Pragmatically, what this means for translating Frobenius is not only correcting (using current standards) the inaccuracies in names of places and people, but also analyzing the origin and proliferation of these errors. It means substituting words that have derogatory meanings with today’s accepted scholarly terms (with the caveat that even these new terms might change in the future). Thus, the notorious “n-word” becomes “African,” “hut” becomes “house” or “building,” “settlement” becomes “city” or “town,” “tribe” becomes “ethnic group” or “people,” while “indigenous” becomes “local.”27 It means using the now almost globally-standardized architectural terminology when Frobenius refuses to name built elements on the African continent as “Architecture.” Here, “rod” and “post” become “column,” “mud” becomes “earth” or “clay,” while “a special hood mold above the door, supported by columns” becomes simply “portico” or “porch.” In a postcolonial and decolonial translation, “the Maasai” becomes “the Maasai ethnic group” in order to resist a language that over time and through hidden codes objectifies and consigns Africans to anachronistic time and space. And “the Bantu race” is replaced with the rather clumsy “Bantu language family speakers” to reinforce the now-accepted dissociation of “Bantu” as a linguistic family from the discredited idea of a “Bantu” culture or ethnic group.

Rewriting Hermann Frobenius means doing a comparative analysis of Frobenius’s text and his sources and noting cases of verbatim citation, cases where Frobenius contradicts or distorts his sources in both his written text and his illustrations, and comparing them to the most up-to-date scholarship on each topic. It means engaging deeply with secondary literature in architectural history, anthropology, archaeology, history, literary studies, and other disciplines. Rewriting Frobenius means creating a parallel critical and explanatory text (“annotations”) alongside my retranslation of Frobenius’s words. Following Brazilian poet Haroldo de Campos, to translate Frobenius is to be a voracious reader, a harsh critic, an “irresponsible hybrid spirit,” and a promiscuous writer in my own right.28

Beatrix Heintze and Adam Jones, “Introduction,” Paideuma v. 33 (1987): 1-17; Molly Callahan N, “Unearthing a Long-Ignored African Writing System, One Researcher Finds African History, by Africans,” The Brink, December 21, 2022, ➝.

Cf. Maxwell Owusu, “Ethnography of Africa: The Usefulness of the Useless,” American Anthropologist v. 80, no. 2 (1978): 310-334; Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983).

Heintze and Jones, “Introduction,” 3-4.

Beatrix Heintze and Katja Rieck, “The Extraordinary Journey of the Jaga Through the Centuries: Critical Approaches to Precolonial Angolan Historical Sources,” History in Africa 34 (2007): 68; John Thornton, “European Documents and African History,” in Writing African History, 259, ed. John Edward Philips (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2005).

Hermann Frobenius, Afrikanische Bautypen: eine etnographisch-architektonische Studie (Dachau b. München: Franz Mondrion, 1894); Hermann Frobenius, Die Moscheebauten im Sudan (Neuhaldensleben: Eyraud, 1896); Hermann Frobenius, Die Erdgebäude im Sudan (Hamburg: Verl.-Anst. und Dr. (vorm. J. F. Richter), 1897).

Frobenius, Afrikanische Bautypen, 49-50.

See Thomas Spear and Richard Waller, eds., Being Maasai: Ethnicity and Identity In East Africa (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1993), 9-14; Robert Fay, “Maasai,” in Encyclopedia of Africa (Oxford University Press, 2010), ➝.

See Chris Lowe, “Talking About ‘Tribe’: Moving from Stereotypes to Analysis,” African Policy Information Center, Background Paper 010, November 1997, ➝.

See Gregory Maddox, “Leave wagogo, you have no food: Famine and survival in Ugogo, Tanzania, 1916-1961,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Northwestern University, 1988, 3.

See “Stuhlmann, Franz,” ➝; Stuhlmann, Mit Emin Pascha ins Herz von Afrika (Berlin: Kuhnert, 1894), 49, 767, 812.

See Kamusi ya Kiswahili Sanifu: Toleo la Pili {A standard Swahili Dictionary, second edition} (Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 2004).

See Karl Weule, “Tembe,” in Deutsches Kolonial Lexikon 3, ed. Heinrich Schnee (Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1920), 474.

See R. G. Abrahams, The Peoples of Greater Unyamwezi, Tanzania, Ethnographic Survey of Africa: East Central Africa, Part XVII (London: International African Institute, 1967); Susan Denyer, African Traditional Architecture: An Historical and Geographical Perspective (New York: Africana Publishing Co., 1982), 62-63, 246.

See E. Heath, “Nyamwezi,” in Encyclopedia of Africa: Oxford University Press, ➝, retrieved 22 Mar. 2021; R. G. Abrahams, The Nyamwezi Today: A Tanzanian People in the 1970s (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Stephen A. Rockel, “A Nation of Porters: The Nyamwezi and the Labour Market in Nineteenth-Century Tanzania,” The Journal of African History 41, no. 2 (2000): 173-195.

See Isaria N. Kimambo, Gregory H. Maddox and Salvatory S. Nyanto, A New History of Tanzania (Dar Es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota Publishers, 2017), 100, 128.

See James de Vere Allen, Swahili origins: Swahili culture and the Shungwaya Phenomenon (Oxford: Currey, 1993), 1-21; Alamin Mazrui and Ibraham Shariff, The Swahili: Idiom and Identity of an African people (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1994).

See Adria LaViolette and Stephanie Wynne-Jones, eds., The Swahili World (London: Routledge, 2020).

See Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, “The Process of Urbanization in Africa,” African Studies Review 34, no. 1 (1991): 1-98.

Stuhlmann, Mit Emin Pascha, 50, 812. An almost verbatim description of a tembe appears a few years after Frobenius’s in Gustav Meineck, ed. Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahre 1896; amtlicher Bericht èuber die erste Deutsche Kolonial-Ausstellung (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1897), 22.

Leo Frobenius, Der Ursprung der afrikanischen Kulturen (Berlin: Gebr. Bornträger, 1898).

See Seth Quartey, “Missionary Practices: German-Speaking Missionaries Between the Home Committee and Colonial Environment in the Gold Coast (West Africa) 1828-1895,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, 2004, 131.

See Marcel Griaule, Dieu d’eau: Entretiens avec Ogotommeli (Paris: Editions du Chene, 1948).

For a brief description of historical Maasai architecture and an analysis of contemporary Maasai built forms, see R. W. Rukwaro, “The Kenyan Maasai architecture in a changing culture,” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, 1997. Susan Denyer also provides a climate-based explanation for the low profile of historical Maasai buildings in African Traditional Architecture, 103-104.

Beatrix Heintze and Katja Rieck, “The Extraordinary,” 69.

Cf. Marion Johnson, “Interesting Document, Dangerous Translation,” History in Africa 14 (1987): 359-361.

Susan Bassnett, “Postcolonialism and/as Translation,” in The Oxford Handbook of Postcolonial Studies, ed. Graham Huggan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 341; Odile Cisneros, “From Isomorphism to Cannibalism: The Evolution of Haroldo de Campos’s Translation Concepts,” Traduction, Terminologie et Redaction 25, no. 2 (2012): 15–44; Elena Di Giovanni, “Translation as Craft, as Recovery, as the Life and Afterlife of a Text: Sujit Mukherjee on Translation in India,” TranscUlturAl 5, no. 1-2 (2013): 99-115; A. Lefevere, “Beyond Interpretation” or the Business of (Re)Writing,” Comparative Literature Studies 24, no. 1 (1987): 17-39; Haroldo de Campos, Antonio Sergio Bessa and Odile Cisneros, eds., Novas: Selected Writings (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2007), 315; Rainer Guldin, “Devouring the Other: cannibalism, translation and the construction of cultural identity,” in Translating Selves: Experience and Identity between Languages and Literatures, eds. Paschalis Nikolaou and Maria-Venetia Kyritsi, eds. (London: Continuum, 2008), 113-114; Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1-14.

On the problematics of the “n-word”, see Emily Bernard, “ “Teaching the N-Word,” The American Scholar, September 1, 2005, ➝.

Haroldo de Campos, quoted in Guldin, “Devouring,” 114.

Appropriations is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and CIVA Brussels within the context of its exhibition “Style Congo: Heritage & Heresy.”