I. The Lightbulb Has to Want to Change

How many psychoanalysts does it take to change a lightbulb? Told at the expense of national or social types, lightbulb jokes poke fun at the excessive effort expended on a paradigmatically simple task. How many ___s does it take to change a lightbulb? Three: one to hold the bulb, two to turn the ladder. Or just one ___ to hold the bulb, while the world revolves around them. Call the union. Drink until the room spins… And so on. The joke finds its denouement in the psychoanalytic version, which shifts the source of humor from the worker’s ingenuity to the lightbulb itself. After so many absurd means of accomplishing the task have been proffered, the end is finally called into question. Suppose the lightbulb doesn’t want to change. A likely scenario, the therapist knows all too well. Laughter now rumbles with nonhuman agency, bubbling up from an imperfectly repressed unconscious resonant with vibrant matter (the object-oriented-ontologist is gratified to note).1

Only from the perspective of a philosopher or historian of technology could lightbulb jokes appear dated to the era of mass electrification. The first, small, geographically isolated power grids were developed in European cities in the 1880s. In 1920, Vladimir Lenin proposed that “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country, since industry cannot be developed without electrification.”2 The Rural Electrification Act of 1936 extended the promise of modernization to an American context. But the first grids were far from reliable. “In the early days of the grid, people didn’t even change their own bulbs for fear of electrocution,” writes anthropologist Gretchen Bakke. “Instead, a trained bulb replacer was dispatched on a bicycle balancing a giant sack of hand-blown vacuum-filled ampules on his back to replace all the bulbs that had burned out during the previous weeks.”3 Here lie the phenomenological implications of Heidegger’s hammer: tools only stand out from the flow of intentional activity when they break. Thus, lightbulb jokes are dated, more specifically, to the hard-won transparency of the socio-technical infrastructure into which the lightbulb is screwed. They presuppose an electrical grid reliable enough to be taken for granted—but just barely. It is no coincidence that they gained popularity in American culture during the 1960s. By then, every fool must have learned how to change a lightbulb.

With electrification came power failures, interruptions to industry and daily life in modern times. Like all “disasters,” blackouts are occasions for trotting out competing narratives about human nature and social relations: here, inherently driven by altruism and cooperation, there, selfish and competitive.4 On the bright side, the 1968 Hollywood comedy Where Were You When the Lights Went Out? commemorates the massive blackout that affected the Northeastern seaboard of the United States in 1965.5 About the same occasion, artist Robert Smithson wrote: “Far from creating a mood of dread, the power failure created a mood of euphoria. An almost cosmic joy swept over all the darkened cities. Why people felt that way may never be answered.”6 Yet, a decade later, the 1977 blackout of New York City conjured foreboding tales of looting and violence in a city hard-hit by economic crisis. Dark times.

Now, suppose we don’t change the lightbulb.

What if we just leave it, burned out in its socket?

That’s not funny.7

II. This Is Not a Modest Proposal

In order to relieve the burdens of overpopulation, famine, and poverty, Jonathan Swift made a modest proposal: feed poor children to the rich.8 Following the paradigm of satire established in Swift’s work, “modest proposals” indict themselves by demonstrating the absurd implications of solving one problem by means of an even more unpalatable remedy. With scathing irony, they reframe the problem and thus the terms of its ostensible solution. Climate change lends itself to such desperate measures, often in the form of ambitious technological fixes that may cause more problems than they solve. Build thousands more nuclear reactors to replace fossil fuels. Block out the sun with sulfur aerosols, mimicking the impact of volcanic eruptions, temporarily reducing global mean surface temperature while wreaking havoc on global weather patterns.9 Install pumps to refreeze Arctic seawater. Create a massive blizzard using snow cannons in order to prevent the collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.10 In each case, the ecological risks are high and the costs exorbitant, potentially outweighing any benefits associated with lowering the mean temperature of Earth—if it works at all. Indeed, the proponents of such schemes are often the first to point this out: “The apparent absurdity of the endeavor to let it snow in Antarctica to stop an ice instability reflects the breath-taking dimension of the sea-level problem,” says physicist Anders Levermann.11

For some scientists working in the arena of geoengineering, demonstrating the absurd measures that would have to be taken to reverse temperature rise operates as a means of advocating for more urgent emissions reductions and carbon sequestration. And yet, as even its most strident critics concede, there will come a time when proposals that now seem outlandish seem plausible.12 If not to a consensus of well-informed decision makers, then perhaps to some rogue actor, who might even embrace the opportunity to weaponize technologies that have the potential to alter weather and climate.13 It would not be the first time.14 If “apres moi, le deluge” was the watchword of the capitalist in the time of Marx, “desperate times call for desperate measures” is the watchword of the disaster capitalist today, a time when catastrophe holds unlimited opportunity for profit. Proponents of field experiments, scenario planning, and anticipatory governance urge us to conduct research and develop best practices now instead of later, when we will be living on even less borrowed time. Through such rational measures, certain strategies emerge as well thought out, familiar, even plausible.15

At a historical moment when it is possible to countenance technological alterations of the biosphere with outrageous cost-benefit ratios, we must consider equally drastic changes in practices of everyday life. Instead of killing the biosphere, what if we kill the engines?

III. The Will to Power

The value of irony will not be lost on us if we approach the matter from a philosophical angle. An argument for reducing our dependence on the constant flow of electricity can be traced from Nietzsche through the Italian Futurists, whose proto-fascist obsession with speed, violence, masculinity, and gas guzzling engines feels perversely contemporary. In relation to technology specifically, they pass on a gross misreading of Nietzsche’s most notorious idea: the will to power. The phrase “Wille zur Macht” first appears as a virtue associated with the figure of the Übermensch in Thus Spake Zarathustra (1883-85). At a key moment in the narrative, Nietzsche’s protagonist, a philosophical prophet of sorts, prepares to take leave of his followers. Realizing that he must not become dependent upon flattery and attention (the Achilles heel of many a guru), Zarathustra resolves to return to his lone mountain wanderings. As a parting gift, he is presented with a staff with a golden handle, on which a serpent twines around the sun. In gratitude, “Zarathustra rejoiced … and supported himself thereon.”16 Leaning upon the staff, he discourses upon the virtue of gift giving and compares the sun itself to the metal from which it is crafted. Beaming and lustrous, “it always bestoweth itself,” but is never depleted; thus gold’s supreme value. “Strive like me for the bestowing virtue,” he tells his disciples. “Power it is, this new virtue; a ruling thought it is, and around it a subtle soul: a golden sun, with the serpent of knowledge around it.” Elsewhere, power is likened to a broad and full river, whose propensity to overflow its banks is “a blessing and a danger to the lowlanders.”17 The Scylla of dependency and the Charybdis of exhaustion gird the narrow path of the will to power.

It cannot escape the contemporary reader that Nietzsche’s images of natural abundance are today harnessed as sources of renewable energy. The river is dammed to generate hydroelectricity. The sun’s infinite generosity is harvested in solar panels and passive design. Earth’s geothermal energy is drawn up from the depths. Wind and waves are put to work at power plants. The so-called “green energy transition” is fraught with political and ecological compromises. Hydroelectricity is imperiled by droughts as mountaintop glaciers melt away under warming skies, while dams wreak havoc on ecosystems and cultural heritage. The rare minerals required to make solar panels and batteries are non-renewable, and their extraction irreducibly exploitative.

Zarathustra’s posture on technology is instructive: he does not hesitate to lean on the golden-headed staff, from which he gains strength, both physically and symbolically. But his use of this tool stops short of the kind of prosthetic dependence on technology that is built into contemporary life. Today, not only physical, but also mental capacities are outsourced to electronic devices. Here we may recall that the Futurists’ valorization of race cars and the “vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons” is an ecstatic fantasy of energy expenditure that ends triumphantly in a crash. A heady vision of masculine overcompensation.18 Yet crash it must, lest it first run out of fuel and sputter unceremoniously to a halt.19

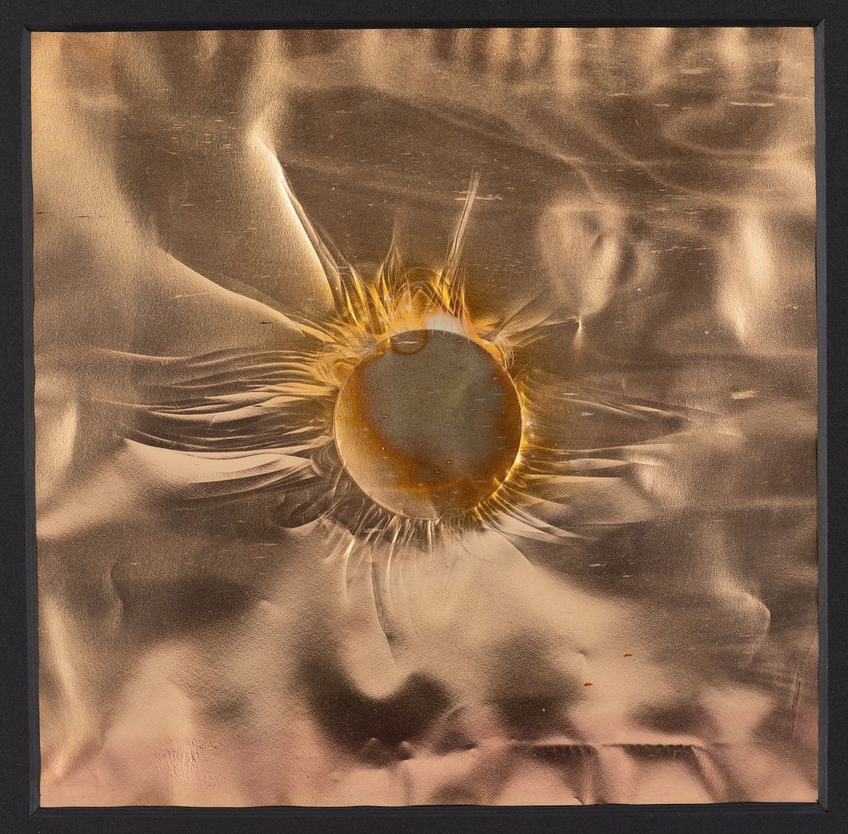

Rohini Devasher, Sol Drawing (2023). Flame, embossing on copper sheet, 15.24 x 15.24 cm. Credit: Geln Cheriton, courtesy of Rohini Devasher and Gallery Wendi Norris.

The will to power must not increase one’s vulnerability to its sudden withdrawal in the form of a “power failure,” a dry gas pump, or a blackout brought on by a computer glitch or a squirrel nibbling on an electricity pylon. Such unseemly dependence is anathema to the flow of forces that animates Nietzsche’s Übermensch. A vision of the good life must not be erected on a finite supply of materials whose extraction and combustion imperil us all. Nietzsche describes the world as “a monster of energy, without beginning, without end, a firm, iron magnitude of force … a sea of forces flowing and rushing together, eternally changing.”20 The question, then, is how to plug in to this play of forces without exhausting them, or becoming so dependent upon them that they no longer empower us.

As elaborated by George Bataille, the will to power must tap into nature’s excess, indeed, its overflowing waste of energy. Is this the sun?21 Or could this power be a capacity for personal and social wellbeing that surfs the ebbs and flows of matter? Here lies a key misunderstanding of Nietzschean thought: the will to power is expressed through values rather than through might. Through religion, philosophy, and culture, values regulate flows of libidinal energy, of desire and pleasure, and the meaning ascribed to their indulgence or sublimation. The revaluation of values is thus the ultimate power play.

IV. Disaster Environmentalism

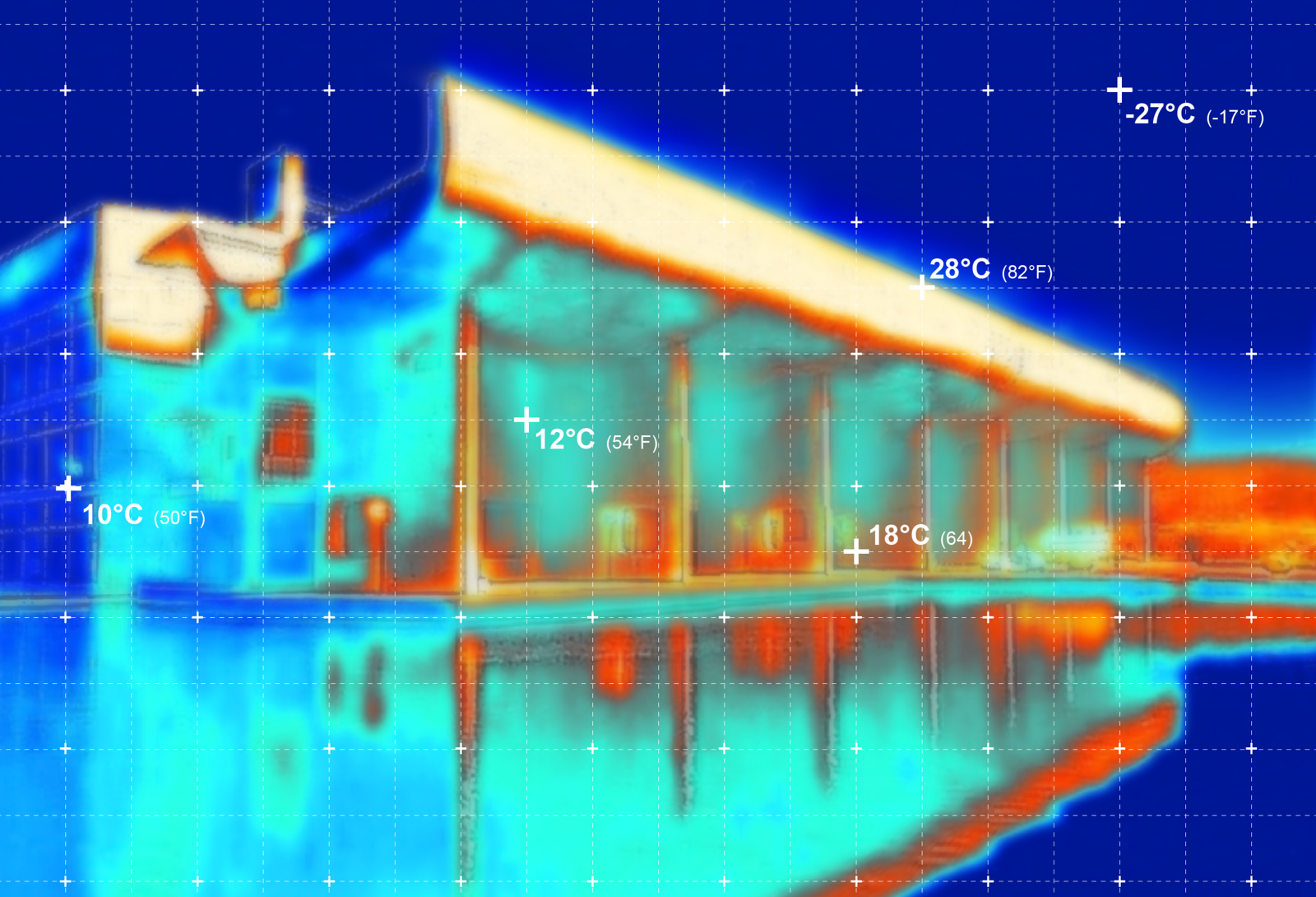

In the wealthiest and most developed nations with the highest per-capita emissions and greatest historical responsibility for climate change, it is time to embrace power outages. Institute rolling blackouts. Design for intermittent power and dramatically reduced consumption. Using the abundant resources and expertise at our disposal, stage blackouts and conduct disaster rehearsals involving police, hospitals, emergency services, basic infrastructure, the general public, and cultural producers. Establish baselines for critical infrastructure. It is time to start pushing back the horizons of perceived necessity. Instead of turning off electric lights for one symbolic “Earth Hour” per year, how many lights and other devices could be shut off for Earth Day? For Earth’s future? Next time a power outage occurs, at home or in some distant place whose mediated reality is delivered to your screen, take it as an opportunity to ask: What really needs to be running right now? Like the inverse to a bolt of lightning that illuminates the night sky, the sudden arrival of darkness allows the stars to become visible. It might be construed as occasion to take stock and reset priorities.

In wealthy nations accustomed to the constant flow of electricity, most people are unprepared for blackouts. Yet much of the world lives with rolling blackouts and unstable grids. The reasons for this are unenviable: war, inequality, uneven development, economic crises, and environmental disasters. Nonetheless, coping strategies abound. If adopted under conditions of less duress, strategies for living with intermittent power could prove exemplary for an alternative model of energy consumption. In a reversal of the troubled logic of development aid, cultural and technical practices for enduring lower consumption scenarios might flow northward from the Global South. For those with the privileges of anticipation and advanced planning, a blackout need not be a disaster. Blackouts, and the coping strategies they elicit, offer blueprints for other ways of living.

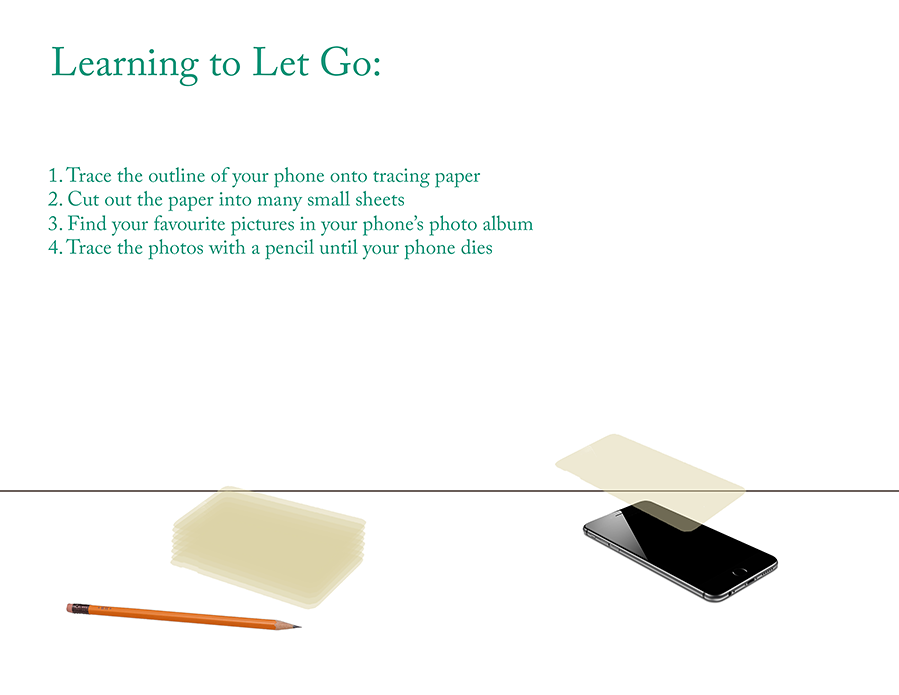

Simon Fuh, Learning to Let Go (2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic and consequent global shutdown of air travel, manufacturing, shipping, etc. has been termed an “Anthropause.”22 This period can be understood as a massive unplanned experiment that enabled researchers to quantify the impact of human activities on wildlife and Earth systems, and created a chance to study how the atmosphere behaves and ecosystems respond when humans retreat. The sudden shutdown of 2020 occasioned an annual drop in global CO2 emissions of an estimated 6.4%—almost as much as the 7.6% drop necessary each year for the next decade in order to keep warming at 1.5 ºC above pre-industrial levels.23 While experienced as extreme, the carbon savings of the global pandemic were still not as much as we would have to get used to in order to avert the worst. The Anthropause invites the question of what it would it look like to sustain such a low emissions scenario for a decade—or longer.

Electricity generation accounted for an estimated 30% of the United States’s CO2 emissions in 2022.24 This figure varies dramatically by country, and fluctuates from year to year due to factors including the adoption of renewable sources, shifting consumption patterns, and the vagaries of weather and regional climates. Nonetheless, electricity generation constitutes a significant portion of global emissions and only stands to rise as transport and heating are shifted onto the grid as part of the movement to “electrify everything.”25 Additionally, the imperative to rectify uneven development still demands mass electrification. Even if this does not take place on the prodigiously wasteful scale of history’s highest consumers, and proceeds using greener energy (which is not guaranteed), emissions from electricity generation will grow significantly in the coming decades.

While we have yet to discover how to reconcile elevating, or leveling, mean standards of living with a net reduction in emissions, the 2000-Watt Society, a Swiss research and policy initiative, has estimated the annual energy budget of each person worldwide if there was an equitable distribution of resources as well as a high living standard. To do this would mean cutting average energy consumption in Europe and the United States by 50–85%, which, they suggest, could be met by a mix of dramatic increases in energy efficiency and significant (although not punitive) changes in everyday life, modes of transport, urban planning, etc.26 In order to stabilize the climate and live more equitably within planetary boundaries, it is clear that not only sources of energy but also patterns of electricity use must be reduced within the wealthiest nations as a matter of urgency. As T.J. Demos has argued, even “as the widespread paradigm of disaster capitalism expands, [and] catastrophe offers further opportunities for advancing ever more intense neoliberal and extractive agendas,” from the wreckage there emerge forms of “disaster communalism” in which the arts have a crucial role to play.27 Useful strategies are born in the dialectic between foresight and disaster.

V. Lightning Strike

In the parlance of labor organizing, a wildcat or “lightning” strike is a sudden work stoppage conducted without official sanction. As an act of protest and a demonstration of organized labor power, it is a powerful negotiating tool. Whether large or small, planned or accidental, blackouts have similar affordances. When the grid goes down, the utility companies responsible for its smooth operation are alerted to the need for maintenance and upgrades, while users are forced to compensate and adjust their plans accordingly. Suddenly, the lightbulb joke is on us.

When a lightning strike brings down the grid during severe weather, it too might be thought of as a work stoppage or a nonhuman form of protest. As Jane Bennett has argued, the electrical grid must be understood as an indeterminate assemblage of elements, including power plants, transmission lines, and electrons, as well as their human operators and users, birds on wires and trees growing through them, algorithms and computer glitches, and everything and everyone in-between.28 Agency, Bennett argues, is distributed unevenly through such assemblages, and thus so is responsibility. Without ascribing intent, or anthropomorphizing the cascade of causes leading to a blackout, we might nonetheless take the grid going down as an indictment of business as usual, an invitation to reflect on our own roles within its vast assemblage.

In an exposition of the mind-boggling complexity of the United States’s electrical infrastructure, Bakke points out an unsettling paradox: “the more we invest in green energy, the more fragile our grid becomes.”29 The imperative to mitigate climate change drives the development of “green” energy. At the same time, climate change wreaks havoc on existing infrastructure, not only by increasing the frequency and severity of storms, floods, and fires that directly impact power lines, but also by driving up demand for air conditioning. And yet, as greener energy sources come online, they increase stress on the grid for reasons all of their own. As Bakke explains, this is because “the grid must be balanced; consumption must always match production, for there is as of yet no real means of storing that electricity for later use.”30 As demand rises and falls throughout the day, it is easy to put more coal, oil, or gas on the fire. But imbalances are caused not only by a lack of energy but also by its surplus. On old, patchworked and jerry-rigged grids (which most of them are), solar and wind power tend to overload transmission lines by shining and blowing at off-peak hours. Not only the physical infrastructure of the grid resists the adoption of variable sources of energy such as sun and wind, but also the whole socio-technical apparatus of the grid and the lifestyles that it affords. Indeed, despite record investment in renewable energy prompted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the director of the International Energy Agency recently affirmed that “the single most important barrier facing the expansion of renewable energy remains problems with projects being able to connect to electricity grids.”31 Despite their obvious benefits, renewable energy sources tend to destabilize electricity grids and even lead to blackouts, which lead the companies that operate those grids to resist, by, for instance, lobbying lawmakers or making it prohibitively expensive to connect to the grid.32

Blackouts register this paradox in material terms. On a smaller scale than the Anthropause, yet more intimately felt, they offer opportunities to reexamine our needs and priorities, our capacity for adaptation to different conditions. Rather than fortify our grids and societies against blackouts, such as with coal-fired or oil-based backup systems, why not embrace them as “found” labor actions?

A preliminary understanding of how the grid works suggests other possibilities still. Inverting the logic of the lightning strike and its ability to disrupt production, a coordinated interruption of consumption might be sufficient to unbalance the flow of electricity through the grid and precipitate a power failure. (Consumption here can be understood as a form of labor.) Consider the great big “American-style” refrigerator, which is responsible for a whopping 7% of the nation’s electric bill. Bakke’s recent research on the history of refrigeration demonstrates that far from only being a means of keeping food fresh, electric refrigerators displaced their gas-fired counterparts along with root cellars, milk doors, and distribution systems in no small part because they solved a major problem for power plants, namely by providing consistent baseload consumption. Now imagine a protest in the form of a mass defrosting: millions of refrigerators unplugged for spring cleaning on Earth Day. Or April Fool’s Day. For a system dependent on balancing supply and demand, a sudden boycott could function as a form of soft sabotage.

Compared to pipelines and distribution systems for fossil fuels, electrical grids are easy to disrupt.33 The literature of security and disaster prevention studies explores numerous ways of attacking the grid’s physical and digital infrastructure.34 These scenarios aim at identifying weaknesses in the grid in order to shore up its stability in the face of human saboteurs and unruly nonhuman agencies. The same thought experiments could, however, motivate the development of triage practices for energy consumption in a climate emergency, much as needs and resources are assessed in a medical emergency. Blackouts befall electrified regions of the world regularly. What would it look like for the grid to fail better?

Jessica Segall, Nom Nom Ohm (When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Chandeliers) (2016). Fruit, root vegetables, and rewired chandeliers in a site-specific installation in Essex Market, where two antique chandeliers are rewired to illuminate the gallery using produce from the market as a power source, prior to the market’s relocation for a new high-rise building.

VI. Unplugging Frankenstein’s Monster

Frankenstein is the archetypical figure for critiques of emerging technologies, from test-tube babies to AI. In Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel Frankenstein, Or: The Modern Prometheus, while never made explicit, it is widely held that the creature is brought to life by means of electrification. The reasons for assuming this are both textual and contextual.35 Shelley was acquainted with the experiments conducted by the Italian physician Luigi Galvani and his nephew Giovanni Aldini, who sought to reanimate animal and even human corpses by means of electrical sparks generated with a Leyden jar. The experiments ultimately proved sufficient only to make the bodies twitch uncannily, which Shelley may have intimated by hinting that Victor Frankenstein sought to “infuse a spark of being” into the creature he had assembled. Yet elsewhere we read of his formative encounter with lightning:

we witnessed a most violent and terrible thunder-storm … I beheld a stream of fire issue from an old and beautiful oak, which stood about twenty yards from our house; and so soon as the dazzling light vanished, the oak had disappeared, and nothing remained but a blasted stump … I never beheld any thing so utterly destroyed. The catastrophe of this tree excited my extreme astonishment; and I eagerly inquired of my father the nature and origin of thunder and lightning. He replied, “Electricity”; describing at the same time the various effects of that power. He constructed a small electrical machine, and exhibited a few experiments; he made also a kite, with a wire and string, which drew down that fluid from the clouds.36

This encounter indicates what makes Frankenstein a modern Prometheus: whereas the ancient Prometheus steals fire from the gods and gives it to humanity, his modern counterpart harnesses electricity. Lightning strikes are the main cause of fire that early humans would have encountered. Therefore, Frankenstein’s innovation represents a step beyond stealing fire itself: the theft of its origin. The consequences, as one might imagine, prove even more dire. Prometheus is punished with eternal bodily pain; Frankenstein endures eternal guilt, first and foremost towards the creature he enlivens and then abandons, and derivatively towards those upon whom his progeny wreaks death and havoc. The novel closes with a scene in which the abject creature promises to commit suicide by throwing himself upon a great bonfire at the North Pole to atone for his father’s sin of playing god.

There is a joke that goes: “Knowledge is knowing that Frankenstein was not the monster. Wisdom is understanding that Frankenstein was the monster.” Contemporary iterations of the Frankenstein story largely figure the monster as a robot, cyborg, or artificial intelligence—a being that runs on electricity, and could only meet its end through a blackout or a dead battery. Today, one associates the outlandish technological ambitions of machine learning, genetics, and geoengineering with Prometheanism. Yet in the present, a return to Shelley’s novel suggests that we should not overlook the more prosaic and familiar Prometheanism of mass electrification, which makes the lightning bolt—a tool of the gods—available at the flick of a switch.

One readily forgets the violence inherent in this habitual gesture. “With a flick of the light switch, I am connected to this violent history,” writes Rita Wong, of the devastating impact of British Columbia’s hydroelectric power plants on the Blueberry River First Nations. “The grid connects us to a history of attempted genocide of Indigenous Peoples, the flooding of vast areas of land, intergenerational trauma, the displacement of people and animals from their homes.”37 Turning on the lights connects us to fraught political histories of fossil fuel extraction and the emissions produced by their combustion; to the labor conditions under which rare earths are mined and batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines are manufactured. This violence is personified in Shelley’s electrified creature, a figure in whose company all environs become unlivable. The monster thus translates between ecological and interpersonal violence.38

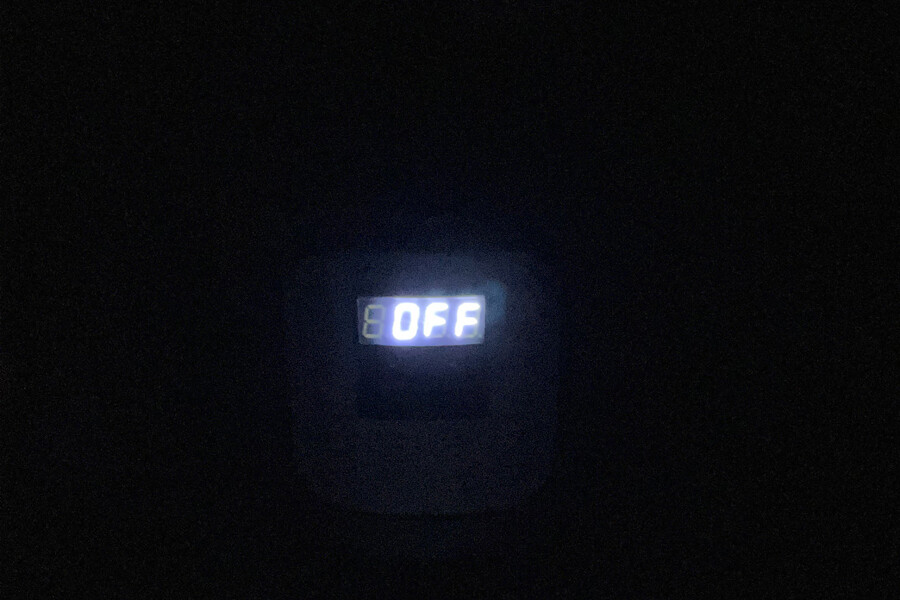

Dehlia Hannah, Pressure Cooker (2023).

VII. Ghosts in the Machine

Another monster haunts us today in the form of “vampire energy,” or energy that is consumed by appliances even when they are switched off, or set on standby; a common vice of chargers, printers, televisions, routers, thermostats, washing machines, and virtually any device with an LED screen or a glaring light indicating that it is off.39 “Phantom loads” (as they’re also known) may account for a quarter or more of a standard household electricity bills, to say nothing of what takes place at the scale of office buildings and industrial machinery, or the water coolers, vending machines, air conditioning systems, and such that run around the clock in buildings and stations even when they stand empty. The scale of electricity waste is staggering. If the rhetoric of haunting pervades discussions of these undead machines, it is perhaps because, in their dormancy, their carbon emissions are equivalent to that of a medium-sized country.

A power failure, whether planned or accidental, represents an opportunity to consider how many of our devices we really want or need to run constantly. At the very least, it may remind us to turn off outlets or unplug devices when they are not in use. This is important not only for energy reduction, but also to prepare the transition to other modes of energy production (and consumption). Whereas coal and gas can be burned in variable quantities to match energy consumption patterns, the wind does not blow on demand. While the sun shines constantly, its rays are intercepted by the earth’s rotation and notoriously unpredictable clouds. “Critics … say wind and solar power are ‘not ready.’ Renewables, they warn us, pose an ‘intermittency problem,’” writes anthropologist David McDermott Hughes.40 And yet, he argues, “For those seriously concerned about climate change, the inverse—the demand for electrical continuity—may be the real problem.” Relying on batteries to buffer the misalignment of supply and demand effectively means kicking the can down the road to the environmental and humanitarian impacts of lithium extraction (to build batteries to store energy from variable sources). Consumption is the elephant in the room.41

Electrifying the First World’s current energy consumption would be catastrophic in its own right, not only because of the minerals required to build batteries, but also because of land scarcity. As the environmental historian Troy Vettese estimates, “A fully renewable system will probably occupy one hundred times more land than a fossil-fuel-powered one. In the case of the US, between 25 and 50 percent of its territory, and in a cloudy, densely populated country such as the UK, all of the national territory might have to be covered in wind turbines, solar panels and biofuel crops to maintain current levels of energy production.”42 Moreover, the long shadow of Jevon’s Paradox looms ominously: increasing efficiency in the use of a resource drives down prices and thus leads to an increase its consumption.43 Thus the giant sucking sound of data servers that accompanies mindless push notifications and streaming media; the immense electrical appetite of generative AI; the proliferation of electronic devices throughout every sphere of domestic life, from housework to sex, and so forth. Indeed, of capitalist growth tout court. How much of ordinary electrical consumption might be revalued as gratuitous waste, destined for the same fate as single use plastic straws wrapped in plastic sleeves, and other monsters?

It is time to expose the vampires to daylight.

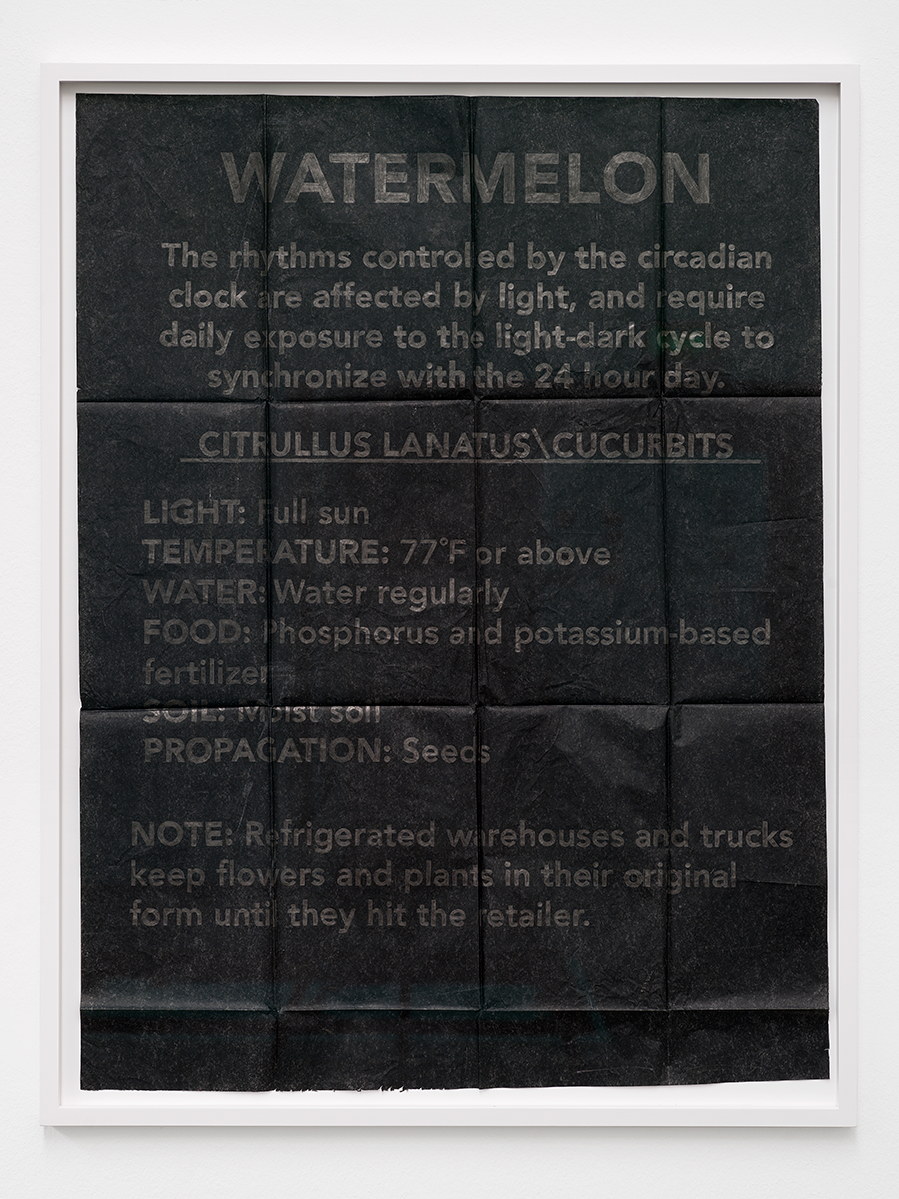

Jessica Vaughn, Watermelon (Plant Drawing Series) (2021). Graphite on carbon paper, 38 in. x 42 in. Courtesy of the Artist.

VIII. Re-Fuse

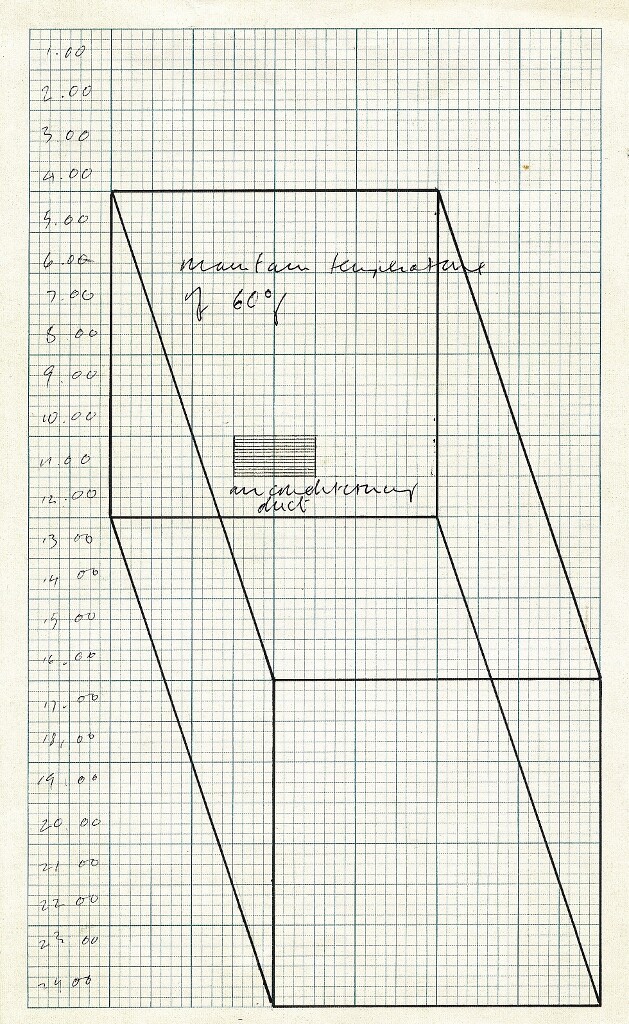

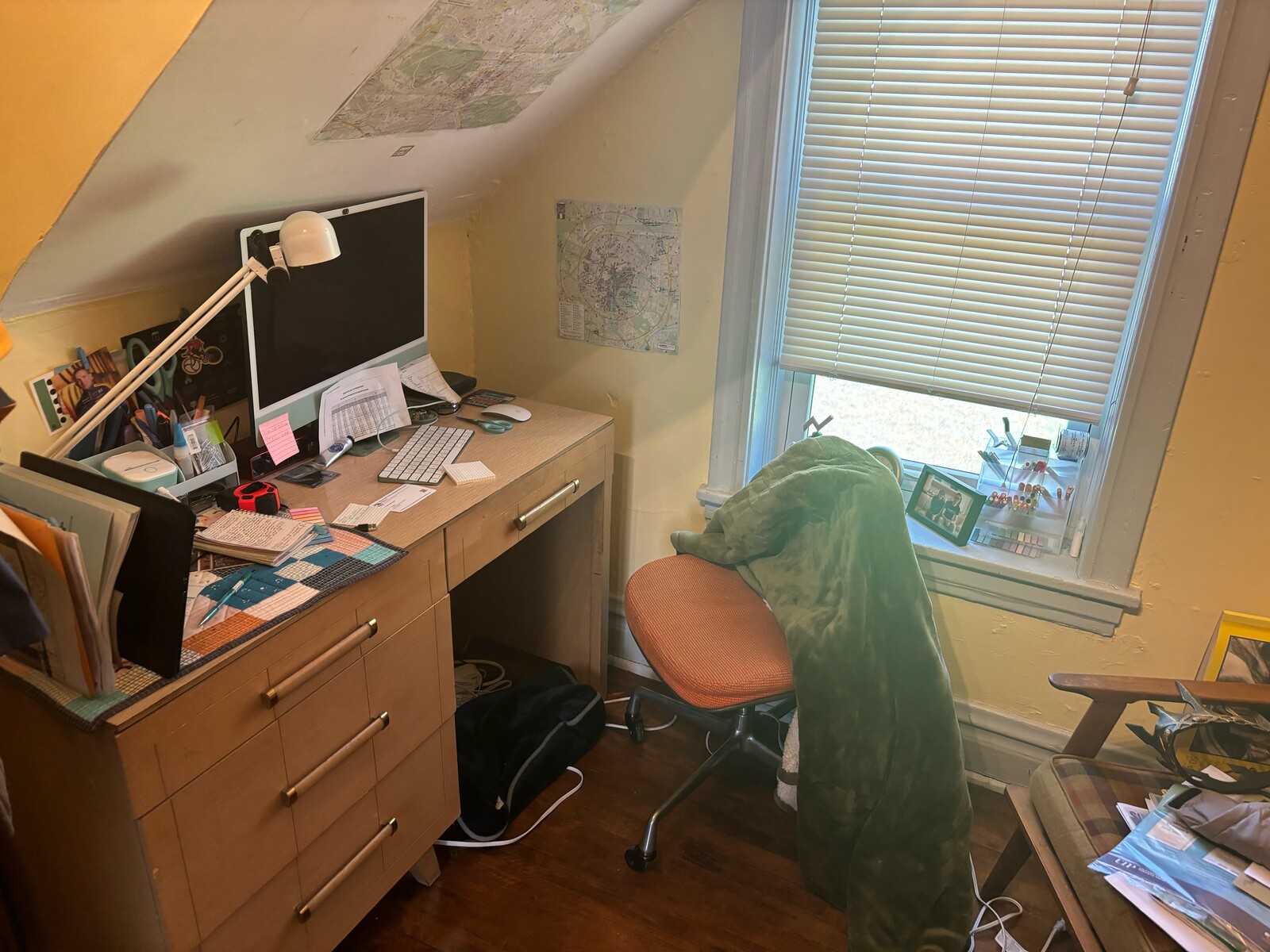

Imagine a fuse box divided into two sections, one containing many well-labeled fuses, the other controlled by a single switch labeled “non-essential.” Connected to it might be all outlets and wired-in devices that need not be accessible on a constant basis. On the “essential” side of the fuse box there might be located some or all HVAC elements, elevators, and refrigerators (or not), an outlet or two for overnight charging of battery-operated devices, and a few lights and key appliances. With the flip of a switch, whenever the occupants were asleep or off duty, it would be possible to disconnect most of the building from the grid, without compromising a baseline specifically tailored to its function. The assignment of fuses to the essential or non-essential category (and other intermediaries) could be dictated by rhythms of use that reflect seasonal changes, work and school schedules, individual differences and preferences, mixed usage of space, and—not least—enculturated habits. Most importantly, the categorizations could be revised in response to experiments in living and shifting norms. Such a “re-fuse box” would make it possible to explore the horizon between basic utility and luxury electrical consumption—a household proxy for the distinction between subsistence and luxury emissions.44 This approach could be applied to existing buildings with more or less facility, and could certainly be taken into account for new designs. One might well imagine an electronic minimalism.

Goodnight vampires.

IX. First World Problems

Electrical consumption is fundamentally aligned with the logic of comfort.45 Heating and cooling are not only responsible for upwards of half of domestic electricity bills, but also increase demand during summer heatwaves, are a familiar cause of blackouts, and are only becoming more frequent and dangerous as the climate heats up. Loss of heating due to power outages during winter storms likewise highlights the border between comfort and necessity. Power outages are sudden and comprehensive. However, thermal comfort affords gradual adjustment by complementary processes of acclimatization: subjective or internal, as the body and mind become accustomed to different thermal conditions; and objective or external, through incremental modification of body temperature. Layer up, strip off, use fans, blankets, shades; consume warming or cooling foods, hydrate, etc. In the same way, we can gradually adjust our eyes to darkness, synchronize household chores and working life with intermittent energy, reject the demand for constant contact and communication, and cultivate an aversion to the constant hum of devices and the prickle of static electricity.

The argument for accepting intermittent electricity supply extends beyond the devices uselessly humming away in empty homes and offices, and can lead to a broader reprioritization of public and private human services. Start by eliminating useless waste in the form of phantom loads. Then press further: how many devices, spaces, and infrastructural elements can be weaned off of a constant flow of electricity? How can habits and cultural norms be changed to accommodate the shifting rhythms of a greener power supply? What inconveniences can be endured gracefully? What unforeseen benefits might flow from going dark?

Accounts abound of the virtues of darkness driven out by ever brightening electric lightning.46 An explosion of research on light pollution charts the health impacts of disrupted circadian rhythms in everyone from insects to shift workers. Here, aesthetics converge with ecological consequence. Yet over-illumination constitutes just one facet of electrification’s excess. Rather than seeking off-grid experiences of wilderness, dark skies, and biodiversity elsewhere—qualitative affordances of uneven development subject to the same extractivist logic as minerals and cheap labor—overconsuming regions might manifest these conditions closer to home, and, along the way, restore circadian rhythms and attention spans, and refuse the relentless acceleration, surveillance, and mediation of everyday life.

Beyond the visible advantages of dark skies and dark screens, blackouts might bring a welcome shift in the charge of the urban atmosphere. The last century of rapid urbanization and industrialization has provoked interest in special qualities of atmosphere associated with certain weather conditions and natural locations, like the sense of well-being common at the seaside, amidst forests and mountains, or after a thunderstorm. It has long been hypothesized that the pleasant effect of the outdoors is due to the unseen influence of electrical charges within the environment.47 Negatively charged ions (atoms and molecules that carry an extra electron) are particularly prevalent in soil, and near plants and rushing water, such as waves and waterfalls (or your shower). Meanwhile, the excess of positive ions in urban areas were considered responsible for a wide variety of maladies, from sick building syndrome to the general malaise of industrial workers.

Chief among the culprits are air conditioning ducts, which strip away electrons as air moves around bends in the metal pipes, producing a profusion of positively charged atoms. While variations occur in natural geographies (historically well remarked are the nefarious influences of foehn or “witches’ winds,” the warm dry air that flows down on the leeward sides of mountains and causes “Foehn sickness”), these insights highlight the ills of being surrounded by positive ion-generating devices.48 This particular diagnosis of the ills of modernity suggests two alternative strategies: escape into nature, or bring its salutary effects indoors. Enter the Russian biophysicist Alexander Chizhevsky, inventor of the Chizhevsky chandelier, a device designed around 1920 to purify the air and thus improve the human condition by creating negatively charged ions. Although the device was later observed to produce ozone at potentially toxic levels, modified ionizers are still widely used as air purifiers today. Electricity itself figures as a vampire device, whose positive ions suck away at human psycho-physical health.

X. Solidarity Blackouts

On winter solstice, December 21, 2022, the lights were switched off at high profile locations across the world in a gesture of solidarity with Ukraine, which had been plunged into cold and darkness by Russia’s precision attacks against its Soviet-era electrical grid. The #LightUpUkraine campaign, led by the Ukrainian government and international aid organizations, aimed to raise $10 million to buy generators for hospitals and critical infrastructure. Two years later, with over half of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure destroyed and the war ongoing, Ukrainians have been forced to devise ways of coping with the energy deficit.49 Affecting everything from traffic lights to centralized heating systems, water pumps and elevators in high rise building, telecommunications, home lighting, and the functioning of schools and businesses, blackouts have forced urban dwellers as well as police, firefighters, and medical services to develop strategies for mitigating the impact of uneven power supplies and come up with alternative sources and ways of distributing precious watts.50

As Ukraine faces another long, cold winter of rolling blackouts brought on by Russian aggression, as Gaza’s inhabitants endure dire fuel shortages and loss of telecommunications, as residents of Beirut and Puerto Rico cope with the long-term, compounding impacts of climate change and neoliberal policies, those of us more safely ensconced must ask ourselves whether we can endure a measure of more carefully planned inconvenience. This may mean burning less of Europe’s stockpile of Russian natural gas. Everywhere, this means taking up less of the planetary budget of carbon dioxide emissions. War presents only one pretext for solidarity blackouts: hurricanes, floods, landslides, unstable infrastructure, and uneven development present so many others. Pick your cause, or stretch your empathy to its limits and keep the power off virtually all the time. The politics of refusal can be implemented at different scales, from private life to architectural renovation and design, to a broader scale of political solidarity.

If we consider how people survive under conditions of privation, we might well learn how to thrive under less pressing conditions. Indeed, overly privileged people tend to enjoy small doses of privation: as theorists of the sublime have long taught, from a position of safety, danger becomes alluring. In a rich, technocratic municipality in command of its electricity grid and emergency services, with a popular public commitment to environmental goals, could we conduct a disaster rehearsal for the public and private sector in which blackouts were programmed to be enjoyed and endured, rather than averted at all costs?

In spring of 2022, German artist Fabian Knecht began collecting donations to support the Ukrainian resistance organization Livyj Bereh. Funds supported the purchase of materials classed as humanitarian help, including medical supplies, helmets and bullet proof vests, vehicles, and power generators. At a time when Germany was enduring gas shortages and surging prices due to the demise of Nordstream II, the artist collected substantial support for power supplies for Ukraine. In the face of the immediate needs of hospitals, schools, and homes, carbon emissions were demoted to lower priority concerns.

XI. Burnout

How many capitalists does it take to change a lightbulb? In 1924, the incandescent lightbulb became perhaps the first example of planned obsolescence, when an international group of lightbulb manufacturers called the Phoebus cartel agreed to set the lifespan of the household bulb at 1,000 hours, reducing the industry standard from 2,000 or more hours—doubling sales of this disposable commodity.51 Another turn of the screw of capitalism. To leave the bulb burned out is to refuse the logic of planned obsolescence and the habituated dependency upon technology that it inculcates, just before breaking down.

Let us have the last laugh.

See e.g. Jane Bennett, “The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout,” Public Culture 17, no. 3 (September 2005): 445–466.

Tim Sablik, “Electrifying Rural America,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond (First Quarter 2020), ➝.

Gretchen Anna Bakke. The Grid: The Fraying Wires between Americans and Our Energy Future (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

On the positive side, Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell (New York: Viking, 2009); on the Hobbesian side, see David E. Nye, When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2010).

Where Were You When the Lights Went Out?, directed by Hy Averback (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer,1968).

Jack Flam, ed., Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

How many feminists does it take to change a lightbulb?

Jonathan Swift, A Modest Proposal (1729; RS Bear, 1999).

As the natural experiment of the eruption of Mount Tambora demonstrates. See Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014) and my A Year Without a Winter (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2018).

Johannes Feldman et al., “Stabilizing the West Antarctic Ice Sheet by Surface Mass Deposition,” Science Advances 5, no. 3 (July 2019).

For a discussion with the authors of the latter proposal, see “Sea level rise: West Antarctic ice collapse may be prevented by snowing ocean water onto it,” Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (blog), July 18, 2019, ➝.

As Holly Jean Buck argues in After Geoengineering: Climate Tragedy Repair and Restoration (London: Verso, 2019), the apparent inevitability of this option must be avoided. Whereas many scholars and activists have argued that geoengineering must not even be countenanced because it constitutes a dangerous distraction from the more urgent goal of emissions reductions, Buck elaborates not only the dangers of the technologies but also of their political and economic administration over the long term—of starting and then stopping, or losing political control over interventions in earth systems. In view of these risks, open minded and serious considerations of geoengineering veer close to the logic of A Modest Proposal.

Kim Stanley Robinson’s science fiction novel The Ministry of the Future (2020) is set in a near future in which, after suffering a devastating heat wave that kills 20 million people, India takes unilateral action to begin a stratospheric injection program equivalent to a “double Pinatubo,” reducing global mean temperature for a few years. The plot device reads as a narrativization of a scenario exercise very like ones considered at the 2017 Climate Engineering Conference held by the Potsdam Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies in Berlin, in which I participated.

See e.g. Tamzy J. House, et al., “Weather as a Force Multiplier: Owning the Weather in 2025” (Air University, Air Command and Staff College, 1996), ➝; and James Roger Fleming, Fixing the Sky: The Checkered History of Weather and Climate Control (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

Rider W. Foley, David H. Guston, and Daniel Sarewitz. “Towards the anticipatory governance of geoengineering,” in Geoengineering Our Climate?, 223-243 (Routledge, 2018).

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche, “The Bestowing Virtue,” in Thus Spake Zarathustra, trans. Thomas Common (1891; Edinburgh: T. N. Foulis. 1909), ➝.

Nietzsche, “The Bestowing Virtue.”

The masculine overcompensation thesis asserts that when men perceive threats to their masculinity, they are more likely to support war or buy an overpriced SUV. See Rob Willer, et al., “Overdoing Gender: A Test of the Masculine Overcompensation Thesis,” American Journal of Sociology 118, no. 4 (2013): 980-1022.

Point 11 of F. T. Marinetti, The Founding and Manifesto of Futurism (1909), trans. R. W. Flint, ➝.

Timothy J. Freeman, “Nietzsche as Ecological Thinker,” n.d., ➝.

See Oxana Timofeeva, Solar Politics (Cambridge UK: Polity Press, 2022).

The term “anthropause” is coined in Christian Rutz, et al., “COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife,” Nature Ecology & Evolution 4 (2020): 1156–1159 (2020); see also Noah S. Diffenbaugh, et al., “The COVID-19 lockdowns: A window into the Earth System,” Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1 (2020): 470–481.

Jeff Tollefson, “COVID curbed carbon emissions in 2020 — but not by much,” Nature 589, 343 (2021).

Congressional Budget Office, Emissions of Carbon Dioxide in the Electric Power Sector (December 2022), ➝.

See e.g. Courtney Lindwal, “Decarbonization: Why We Must Electrify Everything Even Before the Grid Is Fully Green,” Natural Resources Defense Council Explainer, December 1, 2022, ➝; Saul Griffith, “From Homes to Cars, It’s Now Time to Electrify Everything,” Yale360 Opinion, October 19, 2021, ➝; Jesse D. Jenkins, “What ‘Electrify Everything’ Actually Looks Like,” Mother Jones, May–June 2023, ➝.

Roland Stulz, Stephan Tanner, René Sigg, “Swiss 2000-Watt Society: A Sustainable Energy Vision for the Future,” in Energy, Sustainability and the Environment, 477-496, ed. Fereidoon P. Sioshansi, (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011); see also: “2000-Watt society and 2000-Watt Site,” n.d., ➝.

T.J. Demos, “Blackout: The Necropolitics of Extraction,” Dispatches Journal 000 (2017), ➝.

Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Duke University Press, 2009).

Demos, “Blackout”; Bakke, The Grid, 25.

Bakke, The Grid, 25.

Jillian Ambrose, “Invasion of Ukraine ‘has fuelled funding boom for clean energy’,” The Guardian, May 25, 2023, ➝.

For example, Emily Foxhall, Kai Elwood-Dieu and Zach Despart, “Texas power struggle: How the nation’s top wind power state turned against renewable energy,” Texas Tribune, May 25, 2023, ➝.

Andreas Malm and Chantal Jahchan, How to Blow up a Pipeline: Learning to Fight in a World on Fire (London: Verso, 2021).

See e.g. László Erdődi, et al., “Attacking Power Grid Substations: An Experiment Demonstrating How to Attack the SCADA Protocol IEC 60870-5-104,” in Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security (ARES 2022), Association for Computing Machinery (New York, 2022), Article 69, 1–10; Prashant Anantharaman, et al., “Going Dark: A Retrospective on the North American Blackout of 2038,” in Proceedings of the New Security Paradigms Workshop (NSPW 2018), Association for Computing Machinery (New York, 2018), 52–63.

Ulf Houe, “Frankenstein Without Electricity: Contextualizing Shelley’s Novel,” Studies in Romanticism 55, no. 1 (2016): 95–117.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus: Annotated for Scientists Engineers and Creators of All Kinds, ed. David H. Guston (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2017), 24.

Rita Wong, “Blueberry River,” The Capilano Review 3, no. 45 (Fall 2021): 98-9.

When it comes to comprehending the vast, slow, and complex abstractions of structural violence, monsters are good to think with. See for example the now classic epidemiology paper, of renewed interest during the COVID-19 pandemic, P. Munz, et al., “When zombies Attack!: Mathematical Modelling of an Outbreak of Zombie Infection,”in Infectious Disease Modelling Research Progress, eds. J. M. Tchuenche and C. Chiyaka, Eds (Ottawa: Ottawa University Press, Ottawa, 1999), 133-150. On the violence of finance capitalism, see Leigh Claire La Berge, “‘The Men Who Make the Killings’: American Psycho and the Genre of the Financial Autobiography,” in Scandals and Abstraction: Financial Fiction of the Long 1980s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

See e.g. Crystal Ponti, “‘Vampire Energy’ Is Sucking the Life out of Our Planet,” Wired Ideas, April 22, 2022, ➝.

David McDermott Hughes, “To Save the Climate, Give Up the Demand for Constant Electricity,” Boston Review, October 5, 2020, ➝.

Amy Westervelt, “The ‘Electrify Everything’ Movement’s Consumption Problem,” The Intercept, May 8, 2023, ➝. The challenges and advantages of running computers, websites, home heating systems, and myriad other comforts of modern life off of renewable energy sources is explored extensively by Low-Tech Magazine, whose website states “This is a solar-powered website, which means that it sometimes goes offline.” See ➝.

T. Vettese, “To freeze the Thames: Natural geo-engineering and biodiversity,” New Left Review 111 (2018): 63-86.

Blake Alcott, “Jevons’ paradox,” Ecological Economics 54, no. 1 (2005): 9-21.

Henry Shue, “Subsistence Emissions and Luxury Emissions,” Law & Policy 15 (January 1993): 39-60.

Daniel A. Barber, “After Comfort,” Log 45-51 (2019), 40-50, 49.

These arguments date back to the beginning of electrification, see, for example Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s provocative 1933 treatise on Japanese aesthetics In Praise of Shadows (New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1977). Contemporary calls to action include Paul Bogard, The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light (New York: Back Bay Books, 2013); Johan Eklöf, The Darkness Manifesto: On Light Pollution, Night Ecology, and the Ancient Rhythms That Sustain Life, trans. Elizabeth DeNoma (New York, NY: Scribner, 2022).

D. Isitani, “Number of Ions in the Free Atmosphere near Hot Springs,” J-Stage 4, no. 19 (July 1908): 370-377; A. Hartl, et al. ,“Health effects of alpine waterfalls,” Hohe Tauern National Park 5th Symposium, Conference Volume for Research in Protected Areas (June 2013), 265-268.; A. Wiszniewski, “Environment of Air-Ions in Healing Chambers in the Wieliczka Salt Mine,” Acta Physica Polonica 127, no. 6 (2015):1661-1665. For an overview, see Fred Soyka and Alan Edmonds, The Ion Effect: How Air Electricity Rules Your Life and Health (New York: Bantam Books, 1977).

See, e.g., P. Jordan: “Über die Ursache der Föhnkrankheit,” Naturwissenschaften 39 (September 1940): 630–631.

For a current assessment and recommendations see IEA, “Ukraine’s Energy Security and the Coming Winter,” Paris, 2024, ➝.

Tetiana Maloholovchuk-Skrypchenko, “How Ukraine is adapting to frequent blackouts,” Emerging Europe, December 27, 2022, ➝.

Markus Krajewski. “The Great Lightbulb Conspiracy,” IEEE Spectrum, September 24, 2014, ➝.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.

Category

Subject

The current essay began with a course that I taught with curator Nadim Samman at the University of Toronto’s Daniels School of Architecture, Design, and Planning in the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. From the beginning of the winter 2020 semester until the shutdown in early March, students from the Critical Curatorial Lab were engaged in developing an exhibition format to be deployed in an emergency scenario. Conceived as pre-mediation for a moment when patterns of life are radically disrupted, their aim was to examine the affordance of art during a power blackout. Addressing social relations, spectacle, and consumption, the project outcome was conceived as an emergency kit (or an exhibition in a box) and instruction manual (qua exhibition catalogue) to be activated in the event of a future power outage. In light of the very different emergency situation that ensued, only the second part of the project was realized: To mark the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, we released a digital Blackout Manual featuring instructional artworks, student essays, and archival material. While ultimately consuming energy via university servers, the document was offered as a polemic for a speculative method of curatorial pre-mediation. Such a strategy might act as a bulwark against intercession by panic or shock doctrines, when everyday society and culture are up for grabs. Thanks to our students Lilian Ho, Kaixin Li, Leona Liu, Jiaxin Mai, Olivia Musselwhite, Simon Fuh, Talia Goland, Eli Kerr, Seo Eun Kim, and Matthew Nish-Lapidus, and to Charles Stankievech for hosting Nadim Samman and myself as Visual Studies Researchers in Residence during these challenging and thought-provoking months.