This is a continuation of Conservation After Conditioning, Part I: Keeping the World Out

The postwar consensus on preventative conservation emphasized strict control of the museum environment—a control that cheap energy and newly available air conditioning technologies made possible. From World War II to the end of the twentieth century, the ideal museum interior was supposed to keep the world out: to eliminate the natural fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity (RH) that characterize most environments. But since the 1990s, conservation scientists have worried about AC’s carbon footprint and thus started to question this approach. Newer research suggests the flat, unchanging museum environment is likely unnecessary for many types of collections.

Drawing on observational studies conducted in museums as well as experimental data from materials science, Stefan Michalski of the Canadian Conservation Institute has argued that the acceptable ranges for RH and temperature are much broader than once believed. He encourages conservators to study the history of an object or a collection’s environmental and storage conditions in order to discover its “proofed fluctuation,” or “the largest fluctuation to which the artifact has responded in the past.”1 If an object is in acceptable condition, then it is very likely “not susceptible to further mechanical damage from one more event of the same magnitude.”2 Especially cautious institutions, Michalski notes, can ensure their objects will “experience minute or zero damage” by halving any proofed fluctuation.3 Engineering research confirms this with a wealth of data on the strength and endurance of specific materials. Starting from a substance’s “single cycle” stress point—the point at which a single change in, say, temperature would cause immediate breakage or melting—research suggests that changes of one half to one quarter of that magnitude will take one million cycles to cause damage.4 Training materials from the Image Permanence Institute (IPI) likewise suggest that most objects can tolerate any amount of fluctuation—that is, any duration or frequency of repeated cycling through different temperature and RH values—so long as those values lie within the range that conservation research deems safe for it.5

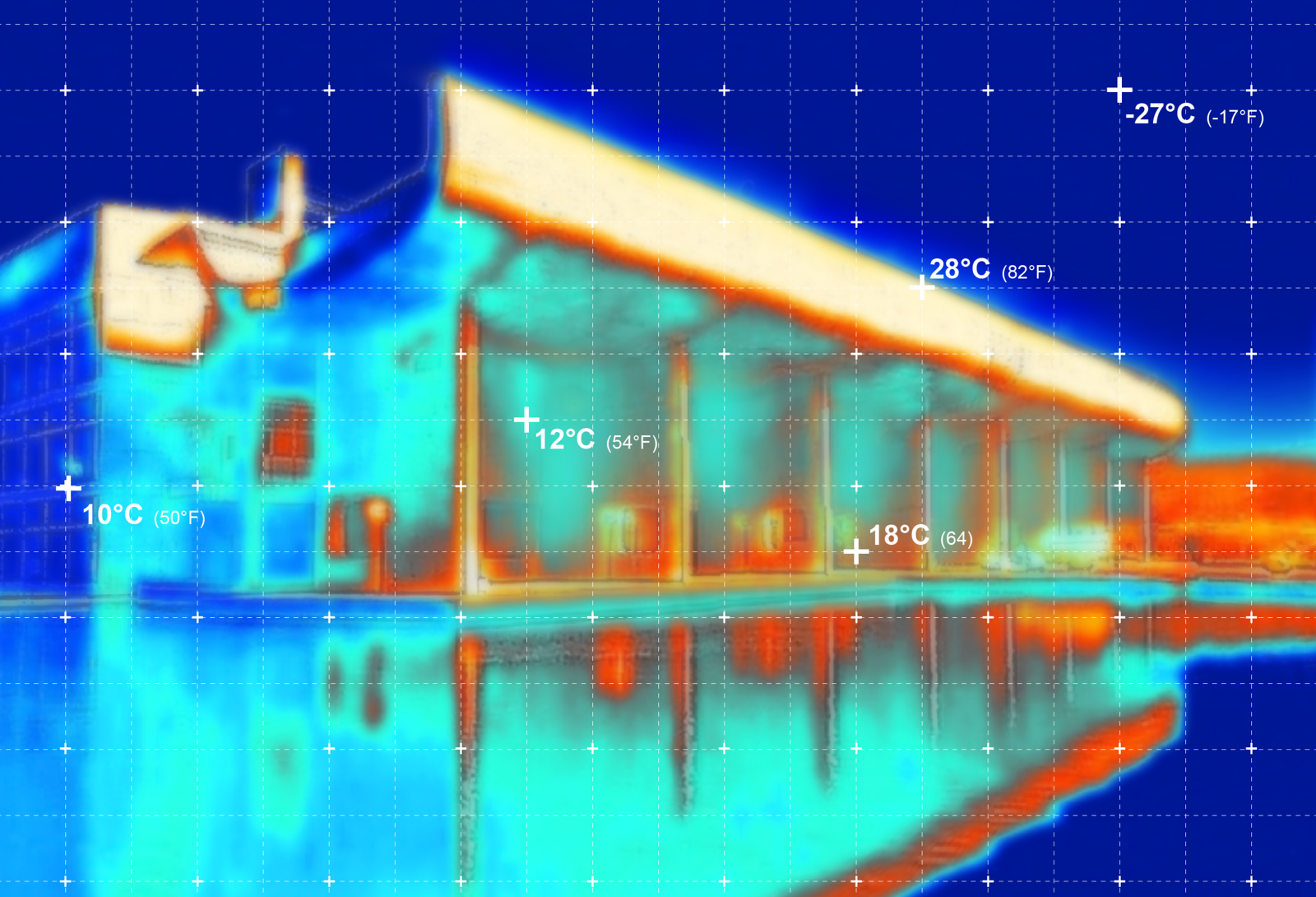

The core theory behind flatlining was that any kind of small physical change in the object will, after enough cycles, eventually cause damage. Though this may technically be true, one million is quite a lot of cycles. To ask that museums hold their climates to tighter standards than that seems absurd in the face of current research. But this is just what loan agreements and insurance policies ask—or, in fact, demand—when imposing the international art world standard of 20/50 ±2-5% RH points or degrees. According to one calculation, museums use as much as 66% more energy to flatline at 50±2% RH than they would if they broadened the acceptable RH range to 50±10%.6 And, depending on the collection, a ±10% tolerance is still very cautious, perhaps overly so.7 In 1994, conservation scientists at the Smithsonian used empirical testing and computer modeling to determine that, for even the most sensitive objects in their collection, ±15% fluctuations from 50% RH were safe.8 Michalski suggests that more robust items, such as furniture and oil paintings, can tolerate up to ±20–40%.9 The temperature fluctuations Michalski deems safe are almost shockingly broad: he suggests that “the great majority” of objects can probably tolerate daily temperature swings as wide as 20–40°C (68–104°F, or, in terms of tolerance, ±34–52°F from baseline).10

Fluctuations themselves, the data suggests, are rarely harmful. Instead, objects suffer from extended exposure to the wrong conditions. The long-term survival of objects therefore depends on the accumulated time they spend in favorable conditions and the avoidance of any immediately destructive extremes. For most collections, this means maximizing time in cooler temperatures, which are, with some exceptions, safe for most types of objects and preferable for many.11 Research by IPI and other institutions also suggests that, depending on climate and material content, some collections can benefit from seasonal RH swings if these have the cumulative effect of increasing the amount of time the collection spends at low RH. This is not because fluctuation is in itself good, but because dry and cold winter conditions are more beneficial than summer conditions are harmful.12 Until recently, the campus of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, Maryland maintained a narrow standard of 45 ±2% RH. Strict flatlining meant that even mild winter heating could dehumidify already dry air to the point where it would need to be re-humidified to stay within such narrow tolerances. In 2011, the archive loosened the RH standards for its stacks to a seasonal 30–50% swing. They discovered that some stacks were able to hold onto winter dryness well into summer, greatly lessening the need for summer dehumidification. The result was better storage conditions with less energy spent.13

Working with, rather than against, natural forces in the protection of artifacts has a long history. In the 1980s, leading Indian conservator O.P. Agrawal encouraged colleagues to use non-mechanical means of climate control traditional to their areas. In Northern India, for instance, woven grass door and window coverings called khas had long humidified homes during the dry summer season; when sprinkled with water, they gently diffuse moisture into the air. Agrawal reported in 1981 that New Delhi’s National Museum used khas over gallery windows as an effective means of climate management.14

The 2,000-year-old practices of the Japanese kura, or artifact storehouse, likewise involve the control of humidity through hygroscopic materials. These structures were typically made of wood, and artifacts were stored in cedar boxes. Many kura were also built raised from the ground or with slatted floors to prevent moisture and maximize air circulation.15 Kura principles guided the 1989 design of a new storage facility for the Archives of the Imperial Household Agency in Tokyo. Made primarily of hinoki and cedar woods, the archive maintains relatively stable storage conditions without the use of HVAC systems. This fact owes not only to the building’s materials and design, but also to what one observer called its “labor-intensive” practices of environmental management. Employees open and close windows according to changing environmental conditions, and every October, when indoor and outdoor climates are at their closest, archivists open every window and unpack every box in order to “air out” the artifacts.16 Ensuring good ventilation and dynamically managing indoor climate takes effort. AC performs this work using fossil-fueled energy, but it is possible for humans to use their own energetic forces—their bodies and minds—to accomplish the same task.

Conservation’s “circular path,” as Sarah Staniforth calls it, has turned to such methods in an attempt to imagine a way out of the era of strict climatic control. In the twenty-first century, she writes, “we find ourselves returning to the traditional, less energy- and resource-intensive practices that enabled our ancestors to maintain in good condition the precious objects under their care.”17 But very few of anyone’s ancestors maintained precious objects in anything like the exhibition culture we have now. The modern museum as we know it is only a little more than 200 years old, and for most of the world, this strange Western institution is still more recent. Meanwhile, museums’ culture of exhibition can stand at odds with preservation. “People are the worst things that can happen to art,” a conservator tells Fernando Domínguez Rubio.18 What the conservator means by this is that people want to see objects and get close to them, but in so doing expose them to their heat, their dirt and dust, their humid breath. Many of the objects hanging in the halls of MoMA or the Metropolitan Museum remain on display for years or even decades; paintings like the Mona Lisa at the Louvre or the Night Watch at the Rijksmuseum so consistently attract patrons that their holding institutions can only rarely afford to put them into storage. Integrating sustainable conservation principles into the art museum thus requires understanding conservation’s historical relationship to display.

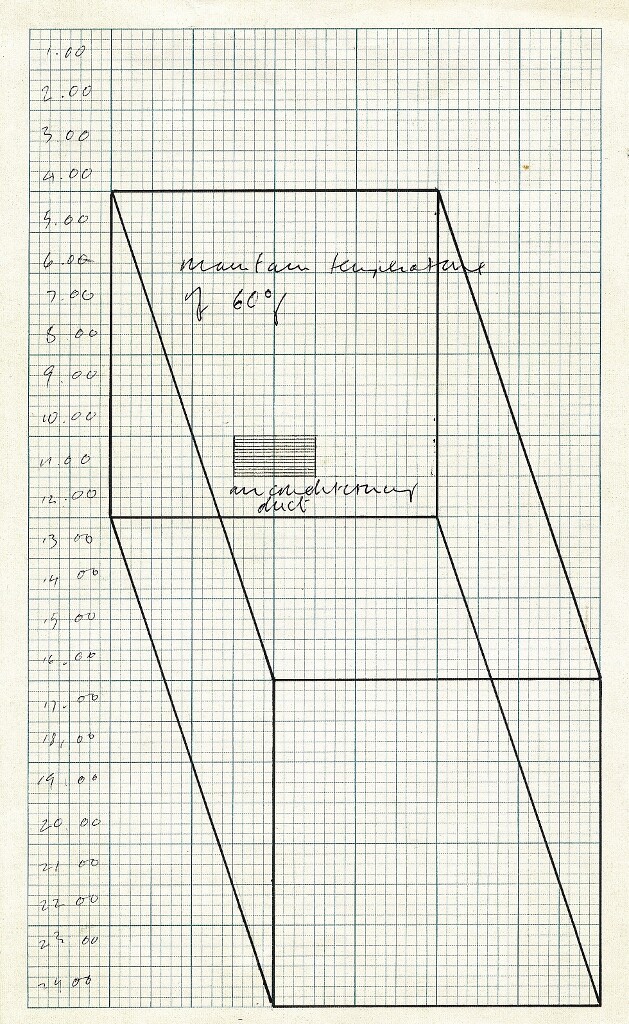

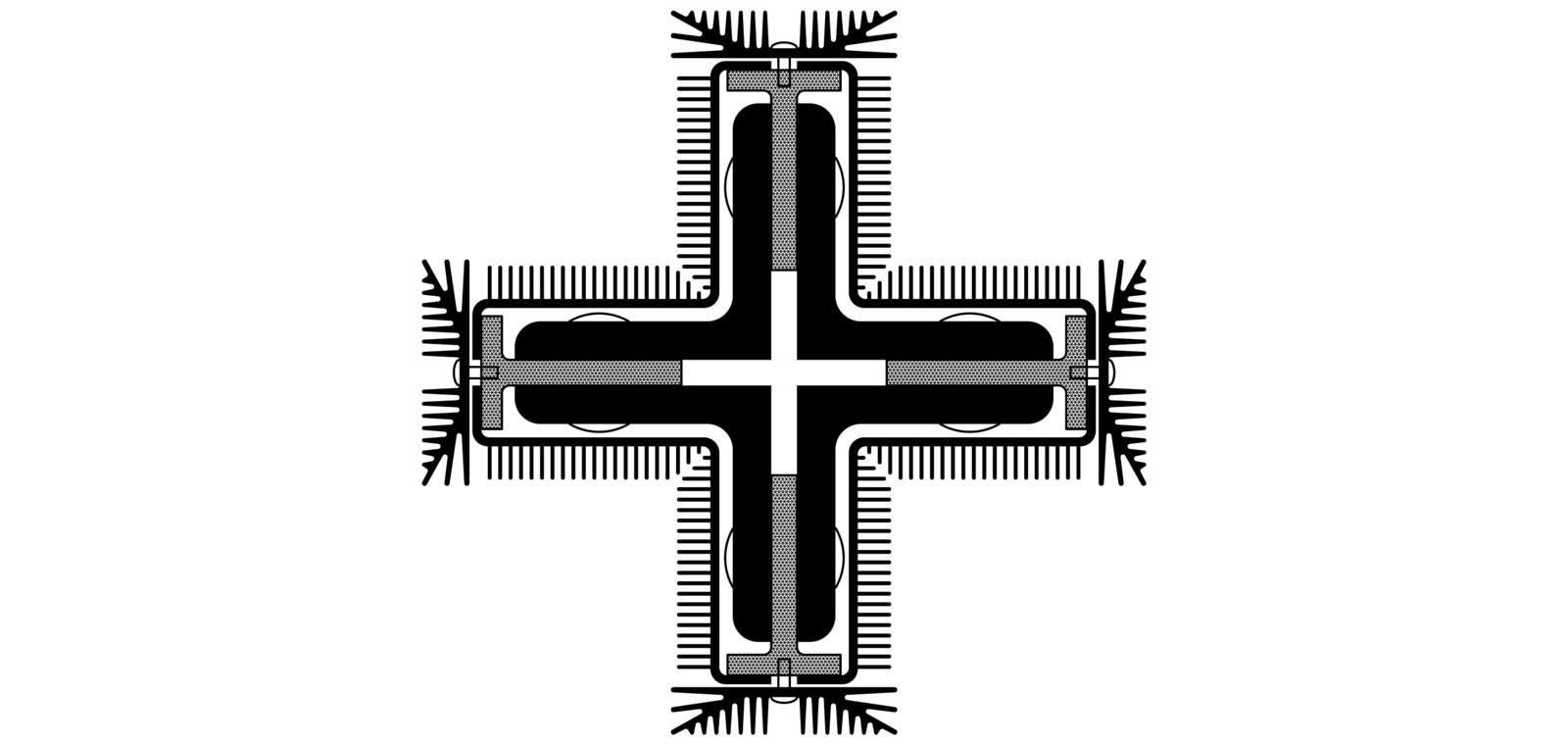

Enclosed frame featuring a sliding drawer for humidity-control salts at the Scottish National Gallery, designed by H.M. Office of Works. From Stanley Cursiter, “The Control of Humidity in Enclosed Spaces,” The Burlington Magazine 69:404 (1936), 230.

From Void to Void

We tend to think of frames as tools for hanging artworks, but they are also technologies of preservation. The vast majority of European and North American paintings from the Renaissance to about 1950 are displayed and transported in frames. The frame’s mode of enclosure is not absolute: it negotiates a constant, subtle exchange between inside and outside. Wooden frames, acid-free mattes, and paper or fabric backings all use hygroscopic materials.19 A well-framed painting is thus surrounded by a sort of RH cushion that mutes fluctuations, providing moisture when a painting is dry and reabsorbing that moisture when it is humid. For centuries, artists and collectors have protected paintings from dust and moisture with varnishes, some of which are meant to be periodically removed and refreshed. Glazing—glass coverings fit into frames—became common in European museums in the nineteenth century due to concerns about urban air pollution, but it was soon found they also protect against heat and humidity.20 By the early twentieth century, many museums had established larger “microclimates” for three-dimensional objects and sculptures by using well-sealed glass vitrines, sometimes with salts or silica inside for passive RH control.21 Frames, vitrines, and other solid enclosures are still valuable tools for maintaining microclimates around artworks. When designed and built with the specific object and the local environment in mind, the right kind of enclosure can protect a piece from heat and humidity without any additional conditioning.22

Frames also serve as protective tools in a formal, aesthetic sense. “The principal function of a frame,” notes one conservator, “is to distinguish the space depicted by the artist from that of the surrounding room.”23 European paintings from the Renaissance through the late nineteenth century typically appeared in spaces where they competed with other colors and designs: they hung on walls lined with boldly colored cloth or paper, alongside drapes and tapestries, above rugs, and surrounded by furniture of all kinds. Such environments, which now feel stuffy and regressive, were surprising havens of sustainable conservation. Paintings hung alongside hygroscopic materials; even their frames leaned against protective layers of paper or cloth. The idea that an artwork would touch a wall’s bare, white plaster was almost unimaginable up until the first decades of the twentieth century.24

In their 1960 “museum climatology” report, Paul Philippot and H.J. Plenderleith urged an audience of museum professionals to use machines for maintaining stable humidity. But they also warned these devices would accrue “little advantage” unless the gallery was more or less filled with hygroscopic materials. The climatologically stable gallery, they wrote, required:

a fair amount of material fabrics, e.g. rough curtains, floor coverings, even furniture, upholstery and so on, all of which act as stabilizers, absorbing moisture when in excess, and emitting it when conditions become too dry. This applies universally; the most spacious and dignified exhibition gallery is scientifically better if it contains some carpeting, furniture, hangings, etc., quite apart from parallel aesthetic considerations. It is perhaps partly on this account that works of art have survived as well as they have in the great country mansions of the past.25

Contemporary research confirms this: filling a room with hygroscopic materials leads to much smaller and more gradual RH fluctuations.26 A still subtler understanding of this principle drives the classic collections management tactic of storing “like with like”: paper with paper, wood with wood, and so on. Books or furniture better bear extreme damp or dry together; they effectively share the load of absorbing and emitting the room’s ambient moisture and correct each other’s extremes because they tend to have similar equilibration points.27 But storage is one thing; exhibiting is another. It is difficult to imagine anything less fashionable today than the scenario Phillippot and Plenderleith describe, at least when it comes to modern and contemporary art. With a few notable exceptions, exhibition spaces since 1945 have adhered to the model of the “white cube.”

Solo presentation of artwork by Gustav Klimt at the IX International Art Exhibition in Venice, 1910, in room 10 of the Pro Arte Pavilion, later known as the Italian Pavilion, designed by Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill.

Like conservation science, the unadorned, white-walled gallery appeared alongside air conditioning. Its emergence is another thread in the tangled web of historical developments that led to the world of 20/50. Though it was by most accounts born in the same decade as AC, the plain white gallery and single row hang of well-spaced pictures had a slow start.28 As Walter Grasskamp details, Joseph Maria Olbrich’s Vienna Secession building was among the first to use “pure white walls” as a background for art hangings. At the 1910 Venice Biennale, Gustav Klimt’s solo show introduced this Viennese exhibition style to a broader audience. Yet alongside these developments there were many key exhibitions of modernist and avant-garde aesthetics in “positively conventional” spaces; New York’s 1913 Armory show, Grasskamp despairs, placed Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase amid “pompous interior design still clearly indebted to the nineteenth century.”29 The white cube gained ground in fits and starts. In 1938, the Stedelijk museum painted gallery walls white for Abstracte Kunst, a show featuring Picasso, Kandinsky, and other modernist painters; a year later Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone’s 1939 MoMA building, an International Style landmark featuring pure white walls, established the style in the United States.30 By the mid-1970s, when Brian O’Doherty wrote a series of essays on the white cube for Artforum, the style was practically compulsory for the exhibition of modern and contemporary art. “A gallery is constructed along laws as rigorous as those for building a medieval church,” he observed. “The outside world must not come in.”31

Layered structure of a framed painting. Canadian Conservation Institute 122309-0001. Copyright Government of Canada.

The traditional function of the frame is not only to protect the painting as an object, but also to distinguish it from the world surrounding it. In this context, the white cube can be understood as a response to a historical moment in which “pictures begin to put pressure on the frame.”32 European painting from the Renaissance on had long deployed perspectival conventions that communicated a sense of spatial integrity, marking the painting’s space as virtual and thus distinct from its surroundings. The frame had a fairly easy job in this era because the easel picture was already “a neatly wrapped parcel of space,” as O’Doherty’s writes.33 But starting in the late nineteenth century, this changed. Impressionism’s optical flatness, cubism’s destruction of perspectival space, expressionism’s slashes of bold color, any abstraction at all: these and other concurrent aesthetic developments made the frame’s task more difficult. Abstract art had an especially hard time standing up to décor without disturbing it—or, worse, becoming it. By offering nothing more or less than the absence of décor, the white wall aimed to minimize confusion as to what was and was not art, or confusion as to where one artwork ended and another began.34 In turn, abstraction and a more “autonomous use of color” flourished when artists knew their work would not have to strain against the “interference” of a traditional museum’s “busy” visual environment.35

The white wall allowed artists to question, fight, and eventually abandon the frame. As a result, paintings shed their traditional protective shells. Works in three dimensions no longer confined themselves to pedestals or vitrines, either. Objects of all kinds sat directly on the gallery floor. These developments, in turn, influenced the way older works were seen. The influential “Weaver Report” of 1947, which recommended the 70°F/50% RH standard, justified its argument for air conditioning by citing curators’ desire to remove museum glass from older paintings and take objects out of vitrines.36 And it is no coincidence that the report was commissioned in the wake of the National Gallery’s controversial Cleaned Paintings show, which exhibited “old masters” paintings recently freed of their thick and yellowing layers of protective varnish.37 Meanwhile, every surface of the white cube was hard and impermeable and, in terms of moisture management, unforgiving. There was nothing in it that would absorb or emit moisture—apart, of course, from the artworks the space meant to preserve. The modern artwork in the modern gallery practically demanded air conditioning.

It would be easy to simply say, in light of recent conservation research, that all this protection is unnecessary—that it is easy to loosen climatic controls within museums, archives, and galleries. But much of postwar Western art, and perhaps a majority of Western art made after 1970, has rarely experienced an uncontrolled climate. A painting or sculpture that has lived its whole life in air conditioning has only the narrowest sort of “proofed fluctuation”; barring blackouts and other extraordinary circumstances, we have little direct evidence of what ranges in temperature and RH newer artworks can accommodate. Furthermore, materials-based modeling has limited application in contemporary art given the fact that twentieth and twenty-first century artists employ a vastly expanded range of materials. Newspaper, house paint, tinfoil, fluorescent lights, plastic, foam latex, lard, lead, chocolate, foodstuffs of all kinds, boxy cathode ray tube TV monitors, preserved or taxidermized animals: all of these materials have, in very different circumstances, entered collections and cycled through conservation departments. In many cases, conservators of contemporary art are stewards of a concept that must be rematerialized with every exhibition; in others, they are forced to adopt a strategy of “managed decay.”38 But to the extent that some of these objects are stable, many of us want to keep them so. It is not so easy to flip off the switch.

Some Proposals

The “20/50 rule” did not emerge from the discovery of an ideal climate for artworks and artifacts. Rather, it is the effect of a historical process through which air conditioning, scientific conservation, the white-walled gallery, and the formal-material characteristics of modern and postmodern art developed in relations of mutual dependence. This AC-conservation-exhibition-artwork complex is so tightly woven as to seem natural and given. But within this net of crisscrossed dependencies, conservation has started to denaturalize its relationship to air conditioning and thus call the entire complex into question. Conservation scientists’ findings make it easier to imagine a world in which the exhibition and storage of artworks expends less energy, in which museums restrict their use of AC, employing it only to prevent harmful extremes. Many collections of painting and sculpture in the Global North currently enjoy unnecessarily rigorous controls, yet they are far less needful of AC technology than collections in regions of the world now suffering the most extreme weather and climatic instability, as well as collections of chemically unstable yet information-dense media, such as film.39

To see clearly what is at stake when we decide when, where, and how much to cool or dehumidify a collection is to recognize the need for a more rational distribution of climate control resources. As in so many other spheres of contemporary global capitalism, ensuring the survival of historical artifacts on an unstable earth would require a kind of globe-encircling and participatory planning. But in the shorter term—and at a more easily achievable scale—other opportunities present themselves. How else might we reimagine the AC-conservation-exhibition-artwork complex?

Design or decorate exhibition spaces to respond to objects’ needs. The white cube cannot regulate its own climate. To turn off the AC, or to at least turn it down, institutions could consider modes of display that break with the white-wall regime. In some cases, viewers will need to accept a more distanced, mediated access to the object though frames and glass. Perhaps more intriguing, and more untested, however, is the idea of once again regulating humidity through décor. What if gallery design prioritized, even obsessed over, the hygroscopic? The white cube’s minimalist aesthetic could soften slightly: it could remain white and rectilinear, but with walls lined in some sponge-like white fabric or ceilings accented with some fragrant, moisture-regulating wood. Still more fancifully, imagine a return to the maximalist gallery. Could modernist paintings, minimalist objects, or ironically kitsch sculptures stand up to décor? What would it mean, and how would it feel, to allow art to again compete with all things decorative, including tapestries, quilts, and upholstered furniture? While the past offers food for the imagination, I do not mean to suggest some revanchist return to the stuffy, stately palace museum. Several prominent collections of modern art already display paintings in decorated rooms or alongside objects of craft and material culture, and these institutions have lessons to offer. At the same time, famous examples such as the Barnes Foundation and Farleys House are essentially house museums: testaments to the wealth or taste of great men and women. Must the plush gallery full of fabric and wood inevitably evoke exclusivity and individuality? What would have to change for the decorated gallery to accommodate or promote a more accessible, egalitarian approach to art? Art history and everyday life are full of models apart from the private home that might guide the artful rethinking of gallery space. What about the workers’ club, the art school, the library, or the public park?

In imagining alternatives to the white cube, I am not necessarily thinking of the many individual artists and groups who have used gallery space to critique the museum or offer alternative forms of relation. I am suggesting something far more mundane: gallery design as hygroscopic engineering. The drapes and rugs and fabric coverings of old were not consciously placed with RH management in mind. Knowing what we know now, new gallery decor could be. Conservators and artists could work together on sponge-like sculptures, practical textiles, or other objects engineered to address the needs of specific rooms or works—and designed to complement or comment on them. Energy efficiency is often sold to museums as a cost-saving measure. But imagine an institution’s entire air conditioning budget repurposed for creative reengineering. Imagine the money that now fuels carbon-hungry machines instead funding and feeding art workers.

Put conservation at the center of arts education. From primary education through to MFAs, people who make art would benefit from the knowledge and experience of conservators and other collections workers. All who use materials should know more about their life cycles: where raw materials come from, where they go if disposed, what they will become when they eventually disintegrate. Students should understand the local and global histories of these materials and learn about their ten-, hundred-, and five-hundred-year profiles. They should learn which material combinations are stable and which are not—for most objects that irreparably disintegrate do so because of inherent instabilities or incompatibilities in the kinds of matter they comprise. Many artists, students, and educators already know their materials even more intimately than this, but plenty others might wish they had more opportunities to learn about what lasts under what circumstances, and what does not. And of course, plenty of artists have no truck with eternity and consciously build works that they do not expect—or want—to last. Institutions that collect and exhibit this type of work should not force it to live beyond its natural life. Artists, like conservators, should consider the material consequences of their work on the scale of hundreds of years: how much energy will it take to store the work, to dispose of it, to recreate it, to replace each of its individual components? Finally, artists hoping to make work that outlives them, that endures, should understand that those creations might need to survive in a world without air conditioning.

Replace the “energy-intensive” with the “labor-intensive.” Compared to tight atmospheric control, the traditional methods of conservation that Staniforth champions as “slow conservation” are less “energy- and resource-intensive.” They are also, as Kazuko Hioki notes in his description of the kura, more “labor-intensive.”40 Airing rooms and objects according to the weather and the season, wetting window coverings, performing object condition reports more frequently, simply to get a feel for an object and its life course: these tasks require a staff that is, at minimum, not already at wit’s end with other responsibilities. IPI’s guide to sustainable conservation suggests collections staff conduct detailed studies of their own buildings and collections as a first step towards determining objects’ actual climatic needs. This requires workers have enough time in their schedules to commence a new long-term project while still attending to the other daily needs of the objects in their care. Even gathering reliable, on-the-ground information about a museum’s environment is “labor-intensive.” Implementing the changes those findings would entail requires still more work.

A post-AC world would require workers to monitor artifacts more closely and to manage the museum’s indoor climate in response. Such a world would, quite simply, require more collections workers. From art workers’ positions this is not a problem; there are more ardent hopefuls wanting to enter the collections field than there are positions to fill. A labor-intensive approach to conservation would also mean ensuring, through better pay and working conditions, that museum staff stay long enough to cultivate deep and nuanced relationships to their buildings and local environments. It would mean trusting staff to organize their work in ways that accommodate daily and seasonal cycles. It would mean ensuring workers are not so overburdened that they lack the time to stop what they are doing and take stock of the weather.

Labor-intensive practices require investing in people and skills rather than technical systems. Yet institutions often prefer to spend on the latter. This owes partly to the fact that our age is obsessed, as Andrew Russell and Lee Vinsel argue, with innovation; our institutions pour all they have into new ventures while generally neglecting the less glamorous work of maintaining their own basic functions.41 Innovation comes with the promise of the unexpected boon: the headline show, the breakout star, the digitization grant, the sparkling new wing and its wall of named donors. Charles Esche and Steven ten Thije note that donor-dependent and state-funded institutions alike increasingly demand “constant innovation and the creation of new spaces and new publics” whose short-term impact can be measured in capitalist terms such as “efficiency” and “financial return.” Innovation, they write, comes at the expense of other values: continuity, care, time for careful observation and research, and “consciousness of planet and climate change.”42 When budgets are cut, strapped institutions are often forced to spend on revenue-generating activities such as exhibits, grant-writing, and fundraising. The plodding, behind-the-scenes work of maintaining objects and records that spend most of their time in storage is sometimes the first thing to go in a financial emergency. And when it comes to fundraising, it is much easier to put a donors names on costly new LEED-certified buildings than on improved labor practices.

But institutions also tend to favor resource-intensive investments because labor-intensive alternatives require more people with more skills, and people and skills are risky. People request raises, get sick, and go on parental leave, or they find other jobs and take their skills with them. People form unions, criticize board members, blow whistles, and demand resignations. They join action groups that press organizations to dump board members who profit from weapons manufacturing, extractive mining, private prisons, and fossil fuels.43 Arts labor organizations protest when museums spend millions on innovation—on real estate, expansions, and blockbuster exhibitions—at the same time that they “fire staff and withhold raises.”44 Such disparities are not only harmful to the longevity of artworks and the museums that hold them. They also have environmental implications. New construction is carbon-heavy, while reducing the museum’s carbon consumption will require increased staffing, new kinds of work, and better conditions for collections workers.

Museum workers are increasingly unionizing, thereby gaining new means for making such demands.45 In doing so they should remember that labor and climate struggles are connected. We hear again and again that the resources are not there: that an energy transition would be too costly, that reducing our energy use in any meaningful way would threaten our lifestyles and livelihoods.46 Never mind what the alternative will cost. Those who work in non-profit and state institutions, in the arts and education, are used to hearing it: the money is not there. The money is never there. It is always somewhere else: it is funding the construction of an oil well or the development of a research lab devoted to more efficient forms of fracking. The money pays for the AC that we do not need, or that most of us do not need, in most parts of the world, most of the time. And, with some exceptions, the artworks and artifacts in our care need far less of it than we think. Imagine turning those machines off, or just down—or returning the parts that didn’t matter and keeping only those that did. Imagine never shivering in your office chair in mid-summer. Or accepting the occasional sweaty workday but gaining, in exchange, another collections staff member. Imagine if all of the resources currently funding the world’s unnecessary cooling, heating, humidifying, and dehumidifying could be taken back and directed towards the things we most need and desire.

Stefan Michalski, “Relative Humidity: A Discussion of Correct/Incorrect Values (1993),” in Historical Perspectives on Preventative Conservation, ed. Sarah Staniforth (Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute, 2013), 167.

Imagine a house museum whose collection of furniture and paintings has, a few exceptions aside, remained stable and in relatively good condition for a hundred years. By using historical weather records and studying how the house responds to climatic extremes, one can determine the upper and lower extremes of temperature and RH the collection has survived. Say that this collection has fared well at temperatures ranging from 40°-100°F and RH ranging from 30-70%; the collection’s proofed fluctuation, then, is 70±30°F and 50±20% RH. Note that while the mid-point of this range is very close to 20/50 (68°F and 50% RH), empirical data shows that conditions have swung broadly around that point with few ill effects. Stefan Michalski, “Agents of Deterioration: Relative Humidity,” Canadian Conservation Institute (2017), ➝.

In the example in the previous footnote, that would mean maintaining a climate of 70±15°F and 50±10% RH. Michalski, “Relative Humidity,” 167.

Michalski, “Agents of Deterioration: Relative Humidity”; Stefan Michalski, “Agents of Deterioration: Incorrect Temperature,” Canadian Conservation Institute (2017), ➝.

“Understanding Fluctuations and Equilibrations,” Image Permanence Institute (May 14, 2020), 17-18, 38. See also Charles Tumosa et al., “A Discussion of Research on the Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on Museum Objects,” Western Association for Art Conservation Newsletter 18, no. 3 (1996).

This number comes from a mathematical simulation drawing on European data; the study presumes a 1200 square meter (12,000 square foot) museum located in Rome. The authors calculated a 40% energy savings by moving from 50±2% RH to 50±10% RH, meaning that moving back to a tolerance of ±2% would entail an energy increase of 66.6%. Fabrizio Ascione, Laura Bellia, Alfonso Capozzoli, and Francesco Minichiello, “Energy saving strategies in air-conditioning for museums,” Applied Thermal Engineering 29, no. 4 (2009): 676-686.

IPI recommends these fluctuations stay within the “moderate range” of 30-60% RH. “Understanding Fluctuations,” 35. Keeping this narrow range is important for highly sensitive archival collections of acidic paper, celluloid film, and magnetic tape, though this is mostly because these materials prefer as dry a climate as possible.

David Erhardt, Charles S. Tumosa, and Marion F. Mecklenberg, “Applying Science to the Question of Museum Climate (2007),” in Staniforth, ed., Historical Perspectives on Preventative Conservation,175-176.

Michalski, “Agents of Deterioration: Incorrect Relative Humidity.”

Michalski, “Agents of Deterioration: Incorrect Temperature.”

Michalski, “Agents of Deterioration: Incorrect Temperature.”

In London, for example, the average summer daytime high of 73°F is fully within an acceptable range for paintings and many other object types, while winter lows of 40°F are far from harmful and may even benefit some objects—though visitor comfort would demand such lows were restricted to storage, and the wet British climate would still require some form of dehumidification for certain collections.

“Understanding Fluctuations,” 10; “National Archives extends life expectancy of its textual Records at its College Park facility AND saves energy at the same time,” Press Release, National Archives and Records Administration (May 23, 2013), ➝.

O.P. Agrawal, “‘Appropriate’ Indian Technology for the Conservation of Museum Collections (1981),” in Staniforth, ed., Historical Perspectives on Preventative Conservation, 48-49. Agrawal’s essay was originally written for a UNESCO project documenting non-Western and non-Global North technologies for collection care.

Teiji Itoh, “Kura: Design and Tradition of the Japanese Storehouse (1973),” in Staniforth, ed., Historical Perspectives on Preventative Conservation, 37-41.

Kazuko Hioki, “From Japanese Tradition: Is Kura a Model for a Sustainable Preservation Environment?” in From Gray Areas to Green Areas: Developing Sustainable Practices in Preservation Environments: Symposium Proceedings (Austin, TX: The Kilgarlin Center for Preservation of the Cultural Record, 2007).

Sarah Staniforth, “Preface,” in Staniforth, ed., Historical Perspectives on Preventative Conservation, xii.

Fernando Domínguez Rubio, Still Life: Ecologies of the Modern Imagination at the Art Museum (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020),166.

Domínguez Rubio, Still Life, 167.

Stephen Hackney, “The Evolution of a Conservation Framing Policy at the Tate,” in Museum Microclimates: Contributions to the Copenhagen Conference (Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark, 2007, 229-236.

Jerry Shiner, “Trends in Microclimate Control of Museum Display Cases,” in Museum Microclimates, 268-269.

See Francis Toledo, et al., “The use of glass boxes to protect modern paintings in warm humid environments,” in Museum Microclimates, 237-261.

Hackney, “The Evolution of a Conservation Framing Policy at the Tate,” 229.

Grasskamp, 83.

Paul Philippot and H. J. Plenderleith, “Climatology and Conservation in Museums,” Museum 8, no. 4 (1960): 275-276.

“Understanding Fluctuations,” 46-47.

Equilibration is the state in which an object will, absent further changes in its environment, no longer engage in exchanges of moisture or thermal energy with its surroundings. “Understanding Fluctuations,” 6.

Domínguez Rubio, 221. Walter Grasskamp, “The White Wall—On the Prehistory of the ‘White Cube’,” On Curating, issue 9 (2011).

Walter Grasskamp, “The White Wall—On the Prehistory of the ‘White Cube’,” On Curating, issue 9 (2011).

Margriet Schavemaker, “The White Cube as a Lieu de Mémoire,” Reinwardt Memorial Lecture, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, March 2016, ➝.

Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (Santa Monica: The Lapis Press, 1976), 15.

O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube, 19.

O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube, 16.

Confusion, of course, is never completely avoidable. The white cube’s capacity to elevate everything within it to the status of art is itself the cause of occasional confusion. Once, when I was a teenager and still exhilarated by the idea that art could be anything, I noticed a small, jewel-like metal and glass box sitting directly on the floor of the Detroit Institute of Arts. The delicate machinery inside struck me as beautiful, and so I asked the nearby security guard who had made it and—testing my knowledge—whether it was a Duchamp. The guard doubled over in laughter. The object, it turned out, was a hygrothermograph. Just over a decade later I would find myself again puzzling over this device, then as a collections worker who wondered how all those curves and spikes had come to be, and what they meant for the objects in my care.

Grasskamp, 85-87.

J. P. Brown and William B. Rose, “Humidity and Moisture in Historic Buildings: The Origins of Building and Object Conservation,” APT Bulletin 27, no. 3 (1996): 15.

Traditionalists balked, arguing that the paintings were so shockingly pale and bright. They might have said the paintings appeared too contemporary, too unmediated, too close, but this was just what many of art’s most faithful champions wanted.

See Martha Buskirk, The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

The most fragile objects, it turns out, are the most ubiquitous: magnetic tape, celluloid film, and acidic paper such as newsprint were all created with an eye to mass distribution rather than preservation. Lower temperature and RH can extend their lives profoundly, but they live on borrowed time. Small changes in these objects trigger profound and information-erasing effects because of the fact that their actual informational value is encoded in miniature form on their surface. The secret to their conservation is relatively simple, however; it involves being as cold and dry as possible.

Hioki, “From Japanese Tradition.”

Andrew Russell and Lee Vinsel, “After Innovation, Turn to Maintenance!” Technology and Culture 59, no. 1 (January 2018): 1-25.

Charles Escne and Steven ten Thije, eds., Towards an Infrastructure of Humans: Working Group Statements, Humans of the Institution, 25-27 November 2017 (Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, 2017), 8-9.

See StrikeMoMA.

W.A.G.E., “Dear Dad,” March 5, 2010, ➝.

See Anni Irish, “Changing Institutional Culture from the Inside Out: Why More and More US Museum Workers are Forming Unions,” The Art Newspaper, May 18, 2023, ➝.

“We don’t have the money,” complained former US Senator and climate envoy John Kerry in May 2024. Without a dramatic change in funding structures, he argued, the energy transition will fail. The International Energy Agency suggests that 70% of the money needed to fund renewables will have to come from the private sector. It leaves open the question of how to compel profit-oriented institutions to make these investments. Attraca Mooney, “The $9tn question: how to pay for the green transition,” Financial Times, May 5, 2024.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.