In 1965, architect Cedric Price proposed replacing the Palace of Westminster with a “Pop-Up Parliament.” The project sought to redefine the relationship between the people and their political representatives. For Price, this meant making politics visible, which he proposed to do by installing television screens inside parliament and reconfiguring who had access to the political stage. In addition to transmitting politics out of parliament, Price also proposed bringing external politics in, with a dedicated exterior “Rally Area.” This space, which would have sat between accommodation for members of parliament and the parliament building, was to include underfloor heating and nylon covers to protect members of the public from rain. It would, at its simplest, provide a thermally comfortable setting in which to congregate. Jan-Werner Müller describes the Rally Area as an intervention that would have told demonstrators “You are most welcome here.”1

Price planned for his Pop-Up Parliament to be obsolete within fifty years. While one response to the “pop-up” and temporary nature of his intervention might be to reimagine the intersection of politics, architecture, and media anew, another is to recognize that, while the technological apparatus of television was a core dimension of Price’s parliament, the project was fundamentally one of democratization.

Television broadcasting of parliamentary sessions was introduced in Britain in 1989. In Australia, it arrived in 1994 (although sessions had been broadcast by radio since 1946). These transmissions, in the political era of social media, now appear commonplace, even passé. And contrary to Price’s expectation, we have learned that the visibility of politics is not in itself indicative of a “more democratic” democracy. Much like the architectural conceit of glass as a building material that would represent literal and procedural transparency, the quantifiable data of politics’ live transmission paradoxically offers an opaque image of political machinations. Something else, however, in Price’s proposal, might offer an alternative path towards a more accessible politics: the cultivation of thermal comfort.

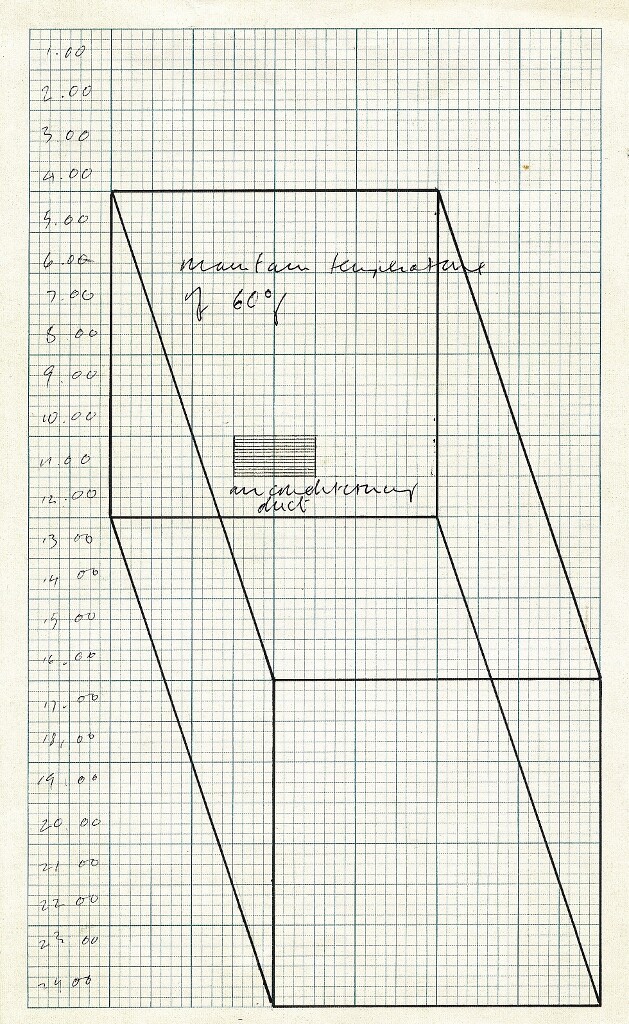

Conceptual sketch for Pop-Up Parliament, London, England, 1965. Source: Cedric Price Archive, Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montréal, File: DR1995:0219:002.

Creating a setting in which the people occupying Price’s Rally Area could safely demonstrate for better political representation was, after all, a central component of the design. In many ways, the project was one of comfort: of, as Müller says, welcoming people into a space of decision making and conferring sufficient comfort that they are able to realize the possibility that comes with political recognition. If Price’s design might have overidealized the potential of television to liberate the populace, what, today, in the age of climate crisis, when there is a need to redefine politics as planetary in scale, might be capable of restaging the message “You are most welcome here”? To put it differently, how might the delight of thermal comfort appear in politics today?

Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright describe the challenge of the climate crisis as requiring “not merely a transformation in politics—more representative proceduralism, for example, or more precautionary environmental policy-making—but a transformation of the political.”2 Mann and Wainwright account for the task of political change through a transformed idea of political organization that disrupts the existing logic of market nationalism with a view to reframing the responsibility of the corresponding democratic force. While the planetary reality of the climate crisis requires a wholesale transformation of the political apparatus, the geopolitical specificity of its happening—the localization of floods, fires, warming, and cooling—demands a local, and, in terms of politics, intimate response. What is needed for the transformation of planetary politics and the various forms of comfort that make those politics hospitable are small-scale revolutions of grassroots change and municipal leadership.

In an era of climate crisis, the “mythic magnitude” of tactics that Mann and Wainwright describe as necessary for realizing life-saving change requires a renewed community of democratic actors. The mythic transformation of formal politics and its agonistic rallying spaces is inevitably part of this, enabling roles and responsibilities to be reshaped. Those who design rallying spaces must resist the construction of spatial hostilities to democratic organizing, and architecturally protect swells of political possibility. Yet new democratic actors must also assume new roles in reshaping spaces for protest and demonstration themselves.

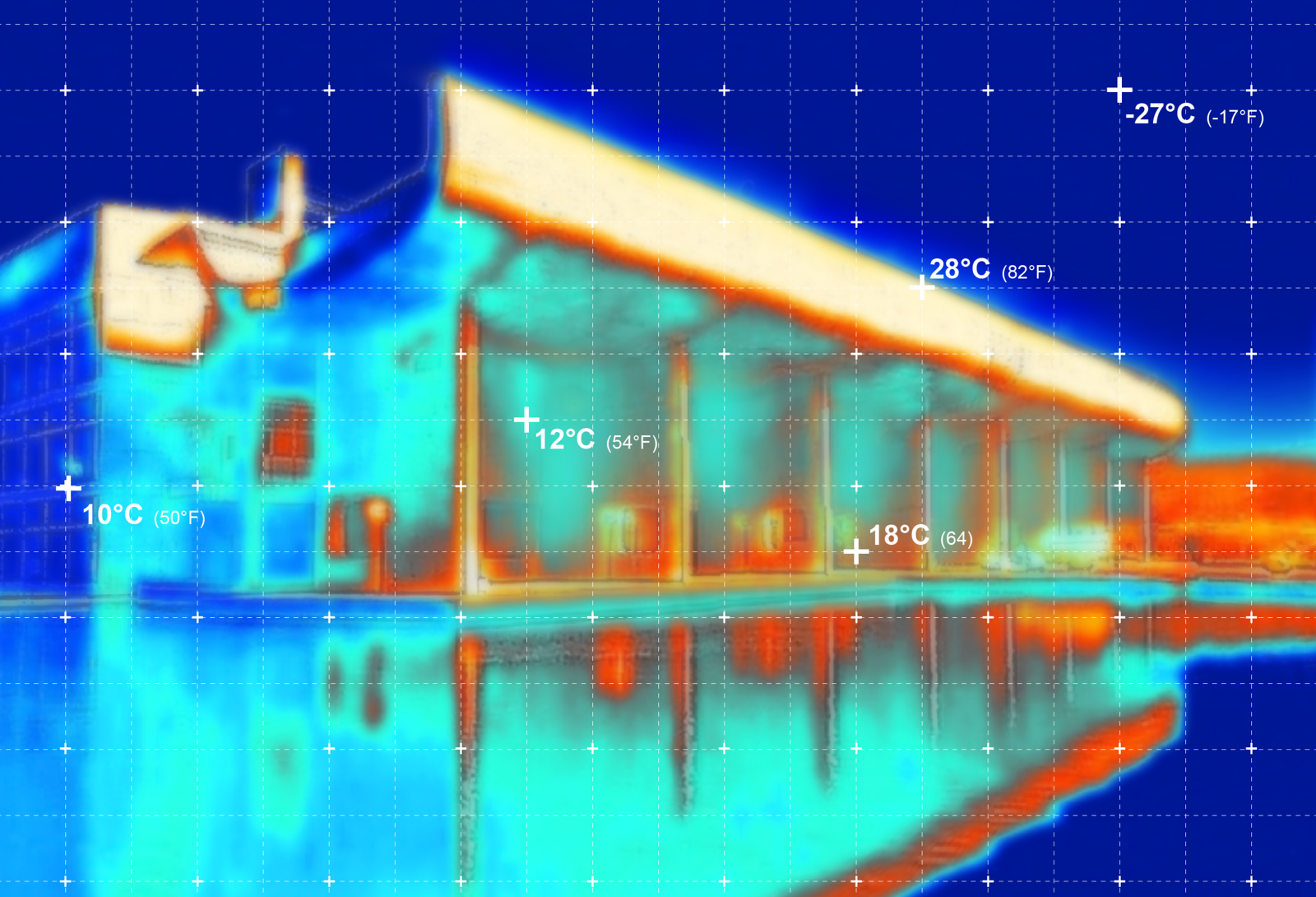

In 2022, the City of Melbourne, a council responsible for the wellbeing of Australia’s fastest-growing city, appointed its first two Chief Heat Officers. Funded in partnership with the US-based Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, Melbourne is one of six cities around the world to have a municipal officer dedicated to reducing heat risk.3 In a continent that was first described as the “sunburnt country” by poet Dorothea Mackellar in 1908, Australian culture routinely normalizes the severity of its weather phenomena.4 Currently, Mackellar’s poetry is deployed in the service of climate denialism in the claim—following another of the poem’s lines—that we’ve always lived in a land of “droughts and flooding rains.”5 As Wendy Walls notes, “Australia has a cultural expectation of living in a harsh environment.”6 Within these environments, the urban is becoming a particularly harsh setting, where, due to urban heat island effects, temperatures can be three to eight degrees Celsius warmer than in rural areas.

The appointment of the city’s Chief Heat Officers is part of a broader strategy to cool Melbourne by four degrees and improve livability, resilience, and community health.7 By identifying, developing, and implementing heat resilient solutions, the Chief Heat Officers assume an architectural role at the scale of the city that recreates the underground heating and rain cover of Price’s Rally Area, but reimagined for an increasingly complex biosphere.

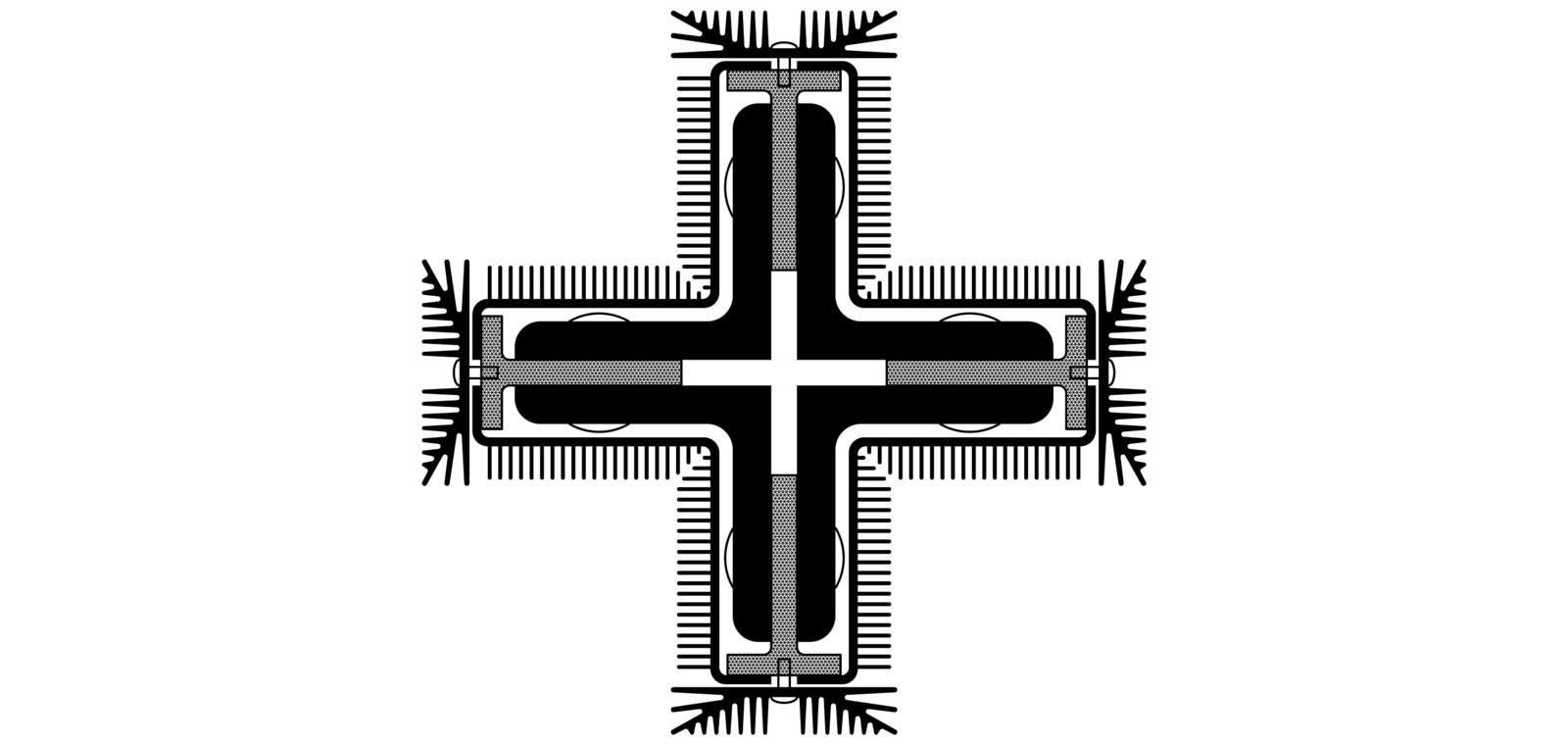

By providing resources for thermal comfort, the City of Melbourne’s own democratic interventions reflect the shift in who and what constitutes the modern demos. Among these tools, and in an attempt to reconfigure urban navigation as a thermally comfortable experience, the Cool Routes project is an online resource that helps Melbournians move through the city via the coolest route, complete with live temperature updates and identification of blue and green infrastructure projects, such as green walls, roofs, tree pits, and stormwater harvesting systems.8 Recognizing that significant portions of the community may not have access to thermally comfortable interiors, an additional map, Cool Places, locates free air-conditioned spaces across the city such as libraries, community centers, galleries, parks, and shopping centers.9 It also notes the location of drinking fountains and tree canopy coverage across the city. The online resource is accompanied by an accessible, printed factsheet on heat and how to stay cool that is handed out during heatwaves.

Highlighting “cool” design features that mitigate ambient heat, the city has also introduced fan-forced mist clouds, splashing fountains, and tree planting to alleviate perceptions of thermal discomfort. Leveraging urban thermal comfort through such “cool” design features while increasing biodiversity across the city, Melbourne’s Urban Forest Strategy aims to increase tree canopy cover by 22-40% by 2040. In a municipality that occupies close to forty square kilometers of space, this increase is not a negligible feat. Conscious of the health risks associated with monocultures, the strategy aims to have no more than 5% of any tree species or 10% of any genus, and no more than 20% of any family.10 The strategy is explicitly linked to climate adaptation. By reducing urban heat island effect and increasing habitat provision for non-human life in the city, councils recognize that comfort cannot be determined by top-down anthropocentric initiatives alone.

To share this thermal responsibility across the public realm, the City of Melbourne offers financial support through the Urban Forest Fund to help local communities and businesses plant trees and influence the thermal comfort of their own neighborhoods. In doing so, the city acknowledges those who will use and care for these spaces most: communities themselves. Street greening projects such as Agnes, Haines, and Howlett Street Gardens were coordinated by residents to create cool and covered common areas for shared use. The democratization of urban greening strategies is a move towards the possibility of communal and shared experiences of comfort. Urban food production has also been driven by the fund, such as with the transformation of the rooftop of a disused parking structure into a small urban farm.11 Produce grown at the farm is donated to Oz Harvest, which provides for families experiencing food insecurity.

These strategies, though centered on the question of thermal comfort, rely on an expansive understanding of the politics and aesthetics of thermal conditions. At their core, they address opportunities for climate resilience at the scale of the city, encompassing and redesigning the realm between the privatized architectures of thermal control and thermal comfort as a democratic right. The reorganization of political bureaucracy to consider thermal comfort stands in contrast to modern architecture’s commodification of thermal conditions in the consumer realms of shopping malls and financialized energy systems. Yet it also reflects a long-held tradition in civic architecture of designing for the public good. Lisa Heschong’s detailed and historical account of “thermal delight” cites the different ways in which the civic is constructed in order to extend thermal comfort to a plurality of residents. She describes the public baths of ancient Rome as “an example of a thermal place that developed into an expression of the social ideals of a society.”12 Like the recent proliferation of “warm banks,” which are spaces set aside to alleviate the thermal discomfort that is produced alongside unaffordable heating mechanisms and poorly designed houses, the Roman baths affirmed a democratic right to thermal comfort.13 Heschong cites the historian Jérôme Carpocino’s description of the baths as “palaces of the Roman people, such as our democracies dream of today.”14

Not all strategies, however, have been successful. Some are slower to emerge and localized to small sites, making their impact harder to assess. The city has struggled to implement green tram stops and green tram tracks pilot projects, and some laneway greening projects were underdeveloped. In certain instances, initiatives were found to be vulnerable to theft, poor growing conditions, and litter. The Greening Laneways project, piloted in 2017 across four city laneways, had partial success, the most successful being Guildford Lane, which had a strong community-led approach to caring for plants, and remains an intimate space for cooling down in the city today. Such interventions evidence the opportunity to reimagine other small thoroughfares as cool veins within the larger, hotter city organism. As historian Weston Bate suggests, one can “take the city’s pulse and temperature from the condition of its lanes.”15

And so, it’s possible that the secret to successful projects is simply that we need more caring communities to execute them. These communities already exist, at least in part. When the Melbourne Urban Forest Map—which documents the lifespan, genus, and location of over 70,000 trees in Melbourne—was created in 2012, each tree was provided with a unique email address so that the public could report damage or sickness tree by tree.16 What resulted instead, however, was a wealth of emails from residents expressing love and gratitude for the trees and the shade they provide. These emails continue to be sent over a decade later. Alongside formal maintenance practices of tree pruning and replacement, these celebrations demonstrate another form of community care in the urban setting.17

Taking a more speculative approach, the City of Melbourne’s Arts House Initiative, a center for contemporary art, ran a six-year project called Refuge (2016-2021), which responded to and imagined responses to climate-related disasters through a transdisciplinary lens, and which also foregrounded Indigenous knowledges and cultures. In 2017, Refuge curated a series of events led by an interdisciplinary team around the theme of “Heatwave,” addressing how Melbourne could respond to a prolonged heatwave and the follow-on effects, such as bushfires, power outages, and food scarcity.18 Latai Taumoepeau, a performance artist, designed a guided exercise workout to understand extreme heat in the city. Hg57 Urban Heat Island Effect challenges participants—community members, researchers, artists, and emergency service workers—to work together to move everyday objects and recognize personal responsibility in emergency events. Within this scenario, and with support from local emergency services, participants were able to share a collective sense of preparedness and autonomy by organizing together in response to a heatwave.

Issues of thermal extremes cannot be disentangled from the complex interplay of other diverse urban issues. Nor can a single group address all such challenges. It is precisely the interplay of place, actors, uses, and design that gives depth to something like thermal comfort to begin with. In her reflections on thermal delight, Heschong draws a parallel between the unsettling effect of a monochromatic world and one with a static and uniform thermal condition. Noting that “we all love having our world full of colors,” she describes the prevailing standard of a “steady-state thermal environment” as an extremely unnatural reality. Instead, she presents the idea of thermal delight, which stems from the stimulation and association of different senses, like the sensation of “coolness” that arises from light filtered through leaves, mint tea, and fresh water. Reflecting on the primacy of fire as an index of thermal comfort, she suggests that perhaps the human fascination with fire stems from the totality of its sensory stimulation. The fire gives a flickering and glowing light, ever moving, ever changing. It crackles and hisses and fills the room with the smells of smoke and wood and perhaps even food. It penetrates us with its warmth. Every sense is stimulated and all of their associated modes of perception, such as memory and an awareness of time, are also brought into play, focused on the one experience of the fire. Together they create such an intense reality of reality, of the “here and nowness” of the moment, that the fire becomes completely captivating.19

Cultivating a similarly intense reality without the discomforting effects that result from current energy generation is the challenge producers of thermal comfort face today. Developing a thermal comfort adequate to the task of realizing the “comfort reparations” that Daniel Barber calls for, especially one that enables both the celebration and extension of a thermal delight and thermal dignity, is a difficult task.20 Reorganizing the bureaucracy of politics to include positions like Chief Heat Officers is one path through this crisis. A more extensive transformation of the politics of comfort is a collective task, one that might only be achieved by reimagining where and how Cedric Price’s Rally Area would be populated today. Building new political formations and assemblages will be central, particularly ones that reorganize public space to be more climate resilient. Also important will be reconsidering the multiple ways thermal comfort can be sourced—not only through the technological interventions of energy-adjusted, personalized, sterile, HVAC systems, but also through interventions that replicate the delight offered by the varied sounds, smells, tastes, and sights of coolness and warmth throughout the city. What a politics of comfort might look like is a city that allows for thermal variation even in extreme events yet still whispers “You are most welcome here.”

Jan-Werner Müller, “Democratic Designs: Show Me What Democracy Looks Like,” The Architectural Review, May 8, 2024. See ➝.

Joel Wainwright and Geoff Mann, Climate Leviathan: A Political Theory of Our Planetary Future (New York: Verso, 2020), 28.

The others are Miami-Dade County, US; Athens, Greece; Freetown, Sierra Leone; Santiago, Chile; and Monterrey, Mexico.

Dorothea Mackellar, “My Country” (1908).

“Droughts and Flooding Rain,” ABC, December 5, 2022. See ➝.

Wendy Walls, “Melbourne Now Has Chief Heat Officers: Here’s Why We Need Them and What They Can Do,” The Conversation, October 18, 2022. See ➝.

“Heat Safe City Overview,” City of Melbourne, ➝.

“Cool Routes Map,” ➝.

“Heatwaves,” City of Melbourne, ➝.

“Melbourne Urban Forest Strategy,” City of Melbourne, ➝.

“Urban Forest Fund,” City of Melbourne, ➝.

Lisa Heschong, Thermal Delight in Architecture (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979), 59.

Warm banks are places where people can go to heat up for free if they can’t afford to turn on the heating in their home.

Heschong, Thermal Delight in Architecture, 263.

Weston Bate, Essential but Unplanned: The story of Melbourne’s lanes (Melbourne: State Library of Victoria, 1994), 12.

“Melbourne Urban Forest,” ➝.

Catherine Phillips, Elizabeth Straughan, and Jennifer Atchison, “Gratitude for and to Nature: Insights from Emails to Urban Trees,” Social & Cultural Geography 25, no. 3 (2024): 363–84.

“Arts House,” ➝.

Heschong, Thermal Delight in Architecture, 29.

Daniel A. Barber, “After Comfort,” Log 47 (2019): 45–50.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.