Fennoscandia is one of the northernmost regions of the planet where vernacular architecture remains prevalent. Although modernization in wealthy Nordic countries has completely transformed ideals of residential comfort, thousands of vernacular log houses still remain in residential use throughout Fennoscandia, the Baltic states, and Western Russia.

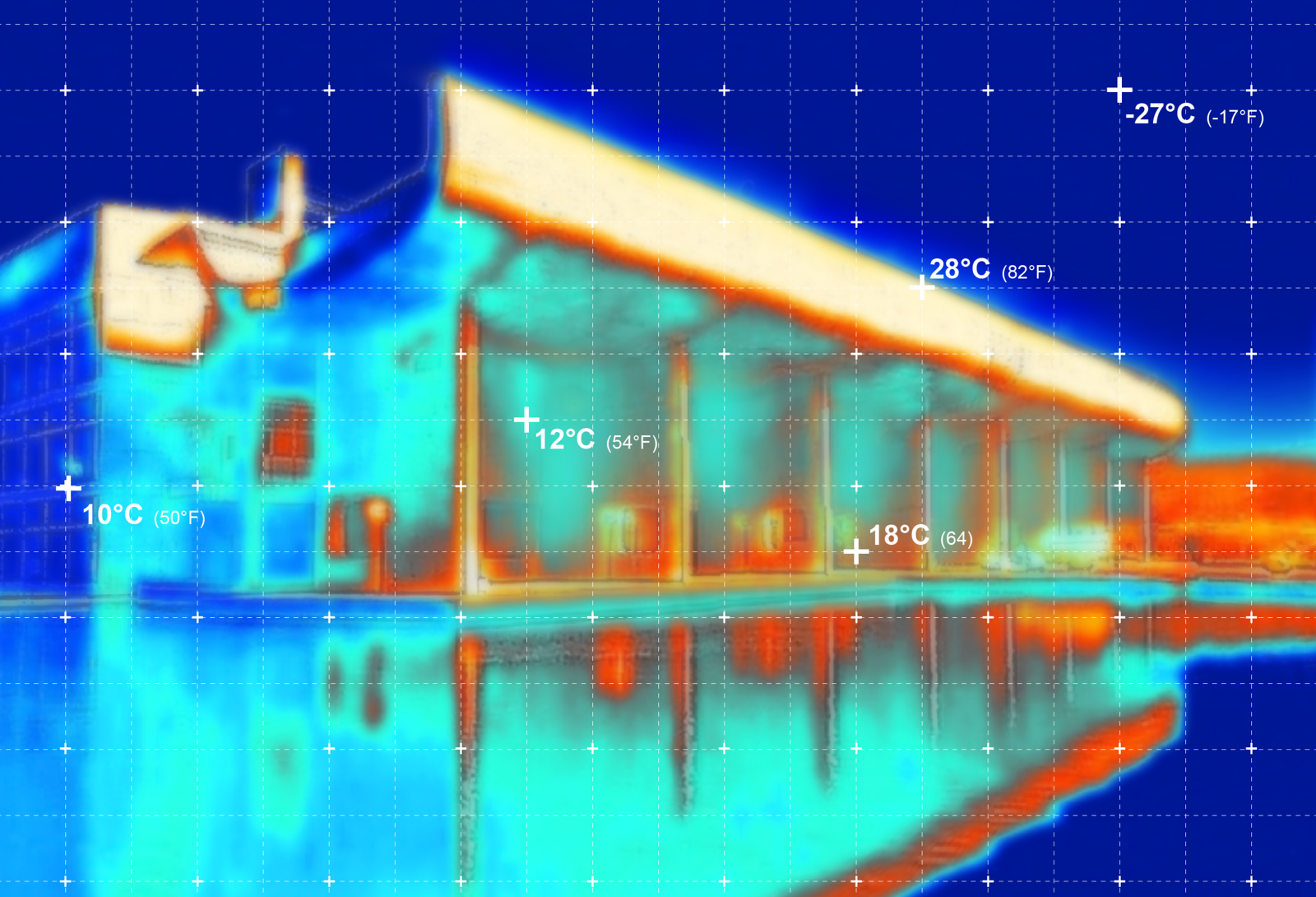

Fennnoscandia is situated on both sides of the polar circle and extends approximately from 60° to 70° North. Although the Gulf Stream makes agriculture possible in latitudes up to nearly 70° North, winter temperatures average between -5 to -15°C, and some regions can dip below -30°C. Humans have lived in this area since the last ice age, and archaeological records present rich architectural evidence of human adaptation to these arctic conditions.

Log house construction emerged in Northern Europe in its present form around one thousand years ago. From the tenth to twentieth centuries, log construction developed in various local forms in different areas. Endemic wood, mainly pine and spruce, was the material source and inspiration for nearly all residential architecture in the region until the early twentieth century. Log houses were the dominant form of rural construction in Nordic countries and the Baltic states until World War II, and in some villages of Russian Karelia until the 1990s.1

A log house is in many ways the ideal form of construction in a cold climate. Logs that are piled on top of each other insulate and, at same time, form a solid, self-carrying structure. Moss can be placed between the logs to further improve insulation. The lack of need for “glue” also allows log houses to be easily disassembled, moved, and reassembled in a different location. Log houses are easily reparable, since rotten logs can be changed without dismantling the whole building, and, if the building is dismantled, reusable logs can be recycled in new buildings. Log houses are also flexible, readily adapting for new rooms to be added or a house to be split in two. Finally, log houses can be simply designed and maintained by their users.

Fireplaces and Zoning

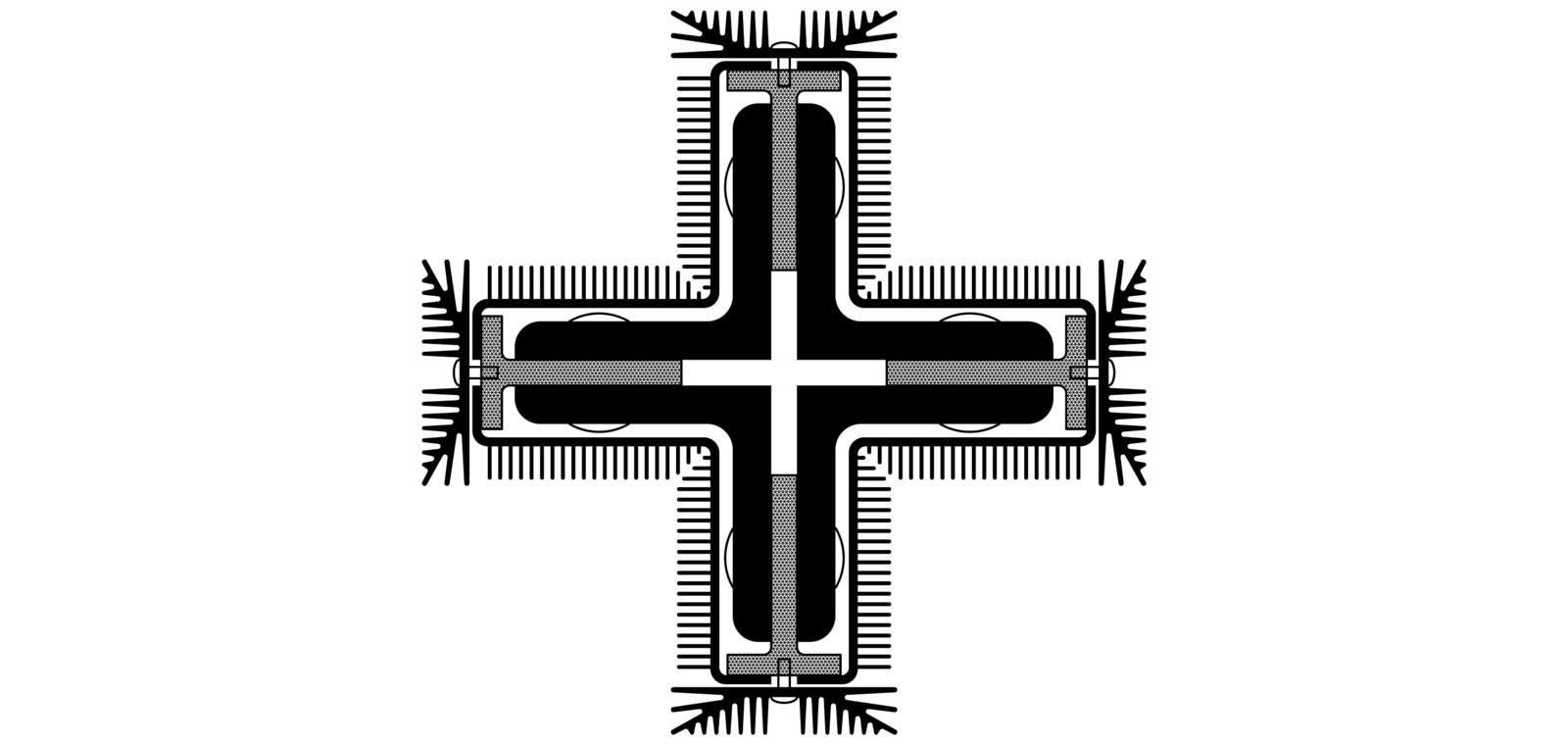

A crucial feature of vernacular log houses is their ability to keep inhabitants warm during the cold winter months. The evolution of fireplaces in log houses is thus inseparable from the evolution of the building typology itself. From around one thousand years ago until the nineteenth century, most of these buildings were smoke houses, meaning that they lacked a chimney. Instead, fireplace smoke rose upwards before being drawn out through holes in the ceiling and timber channels called lakeistorvi. The ceilings were high enough (3.5–4 meters) to allow the lower parts of the indoor space to be relatively free of smoke.

During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, chimneys and tile stoves—previously a luxury exclusive to urban areas—became widespread in the countryside, and many smoke houses were refurbished with them. This profoundly affected the design of residential spaces: tiled stoves were much smaller than smokehouse fireplaces, which made smaller rooms and more varied house plans possible.

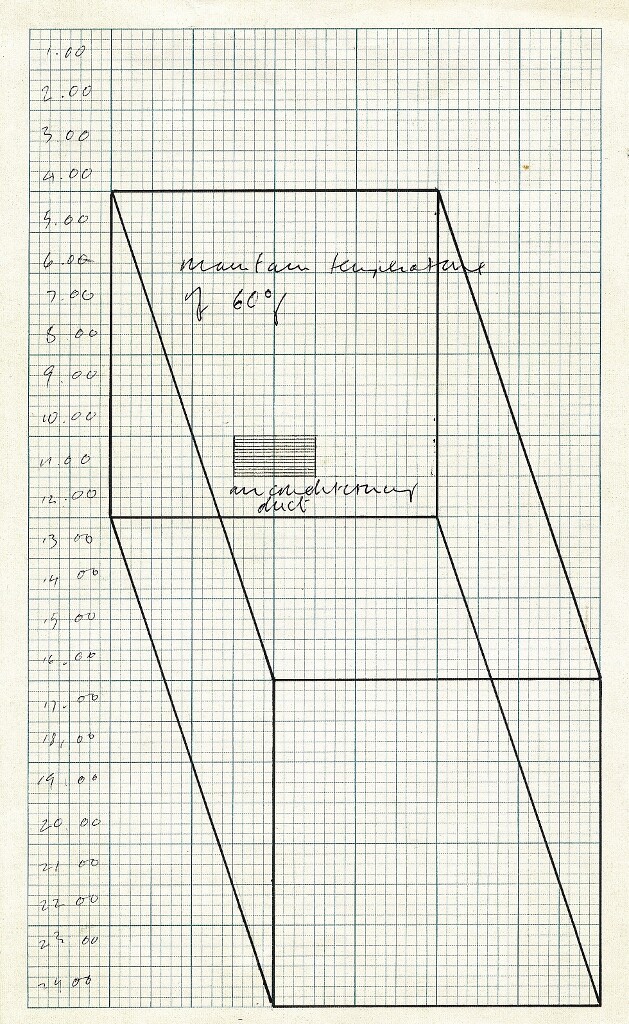

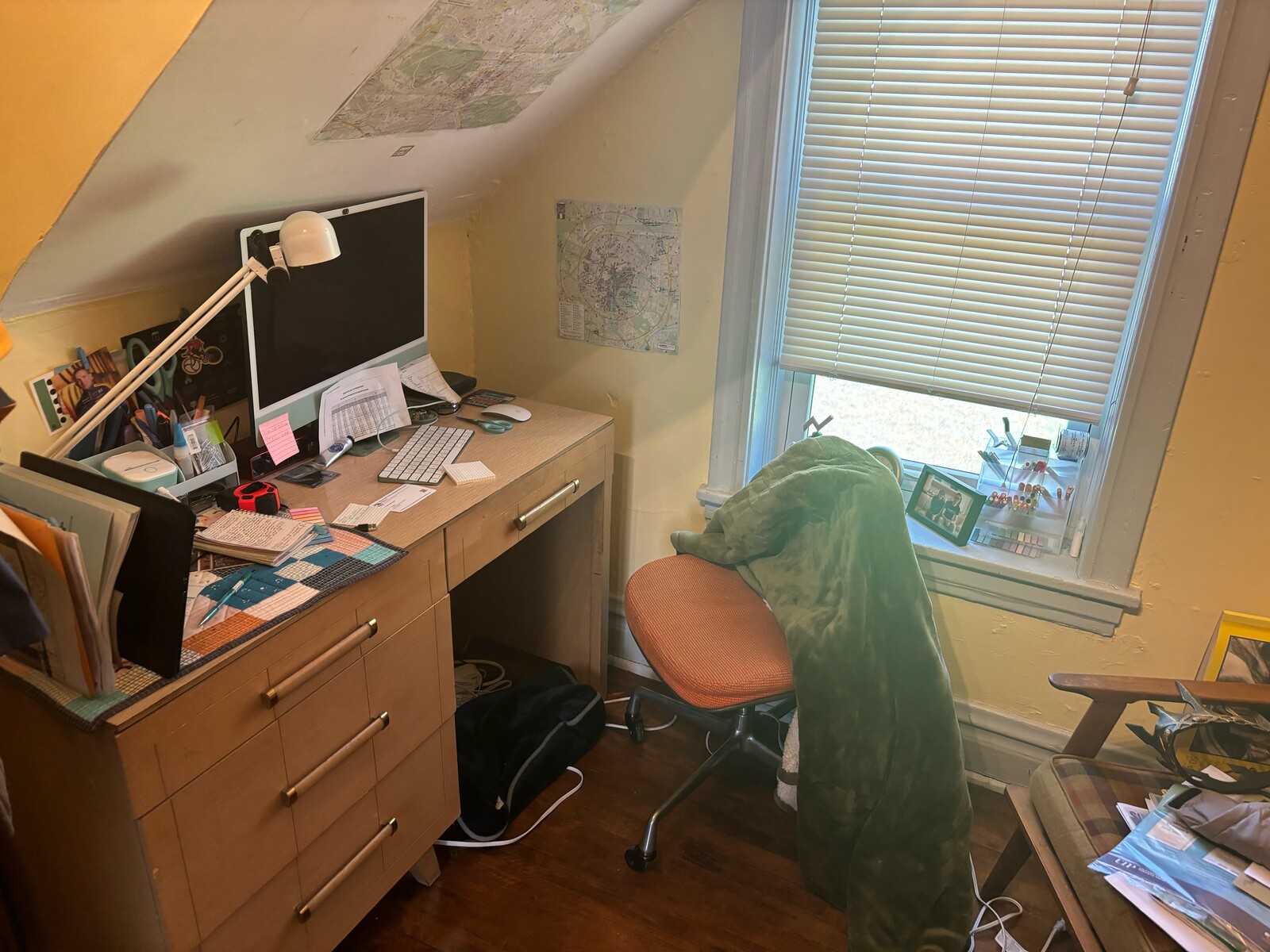

Before the introduction of the tiled stove, log house residents needed to balance the availability of firewood with optimal indoor comfort. This was achieved through interior zoning, or cultivating different patterns of use according to the season and outdoor temperature. A typical vernacular farm consisted of several, even dozens, of separate buildings, each with its own specific function, in part distinguished by seasonal conditions. In the warm summer, residential functions would extend to barns and storage rooms. But in the colder, winter months, only the main residential building, where all members of the household lived and slept, would be heated. Another key element of maintaining thermal comfort across the seasons were warm clothes. Still today, wool socks remain an ordinary piece of winter clothing to wear inside log houses.

Modern Comfort in Vernacular Buildings

After World War II, vernacular log houses in Fennoscandia began to disappear, except in Russian Karelia, where they only began to disappear after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Modern materials and “solutions” replaced those traditionally used in log house construction, and many of these historic buildings were torn down. Concurrently, however, provincial heritage institutions and private house owners began systematic campaigns to protect their vernacular heritage.2 In more peripheral regions of Russian Karelia, there are still today villages filled with well-preserved log houses.

Today, historic wooden log houses close to urban areas make for desirable real estate, be it due to their aesthetics or their context. The way they are inhabited now varies greatly. Some still use original fireplaces that have been carefully conserved, while others have been completely refurbished with modern interiors and geothermal heating. Renovations and restorations are, however, increasingly attempting to preserve the original appearance and structural and thermal performance.

Although new log houses with natural ventilation and vernacular materials are rare, it is a viable alternative for modern construction techniques and materials. Logs are easily recyclable, and log houses are resilient and repairable. A log wall twenty-centimeters-thick can meet modern energy performance requirements, and, as a naturally hygroscopic material, it helps to stabilize indoor humidity.

The vernacular architecture of Northern Europe has undergone thousands of years of evolution, and is testimony to sustainable ways of producing comfort. If past conditions do not meet our modern sense of comfort, wisdom deriving from vernacular architectural might still offer architects critical insights and ideas for how to build and what kinds of thermal conditions, performances, and behaviors we should aspire towards. The contemporary ideal of comfort aims to provide the same indoor temperature and conditions throughout the year. However, we might alternatively think of thermal comfort as being a dynamic condition that changes throughout the seasons.

A. Nissi, G. Grotenfelt, S. Freese, T. Jeskanen, and V. Helander, Hokos, Warma, Voloi. Houses and villages from the Finnish archipelago, Karelia and Ingria (Helsinki: Helsinki University of Technology, 1997).

See e.g. R. Vuolle-Apiala, Hirsitalo ennen ja nyt (Helsinki: Otava, 2016).

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.