The history of the house in which I live is a history of combustion. Erected in 1886, it is one of the earliest post-Great Chicago Fire houses on my block in Logan Square. Constructed from brick masonry, the house rose in the shadow of great flames, yet also in the service of small ones—those found in a central, coal-burning stove. The twentieth century electric revolution came and went, the choice was made to trade in one form of burning for another, and, at some point, the coal-burning stove was exchanged for the gas-powered radiators we have today.

1886 was an interesting time for building science. By that point, much in the building industry had already or was starting to become standardized, such as nail size and lumber grading, considerably lowering construction costs. Houses sprung up like weeds thanks to mass production, and to a railroad logistics system that was fast approaching its early-twentieth century apex. Yet 1886 was still fourteen years before Wallace Sabine came up with the equation for reverberation time. This is what kickstarted the acoustics revolution, which in turn led to many developments in insulation technology as a means of dampening sound. Thus, it wasn’t until the 1920s and 30s that knowledge around insulation began to play a role in a maturing building science.1

Meanwhile, in the late-nineteenth century, many wall cavities in homes were stuffed with newspaper to keep in the heat, if that. My house is bearable in the summer because it was built long before air conditioning and the large windows enable decent cross ventilation. In the winter, however, those windows leak air like a sieve. But this was not the concern of the coal-fired stove era, which tended to solve the problem by blasting heat from a single central source. The only problem is, in 2024, we don’t have one. Instead, we have rather lackluster radiators that are reliant on an extremely expensive fuel source. To live comfortably in the winter would require exorbitant monthly utility bills in the hundreds of dollars. And because we rent, and the costs of refurbishment would be astronomical, a real fix isn’t coming soon. If it came, it would entail stripping the house, removing all of the plaster (which would likely not be replaced), digging into the meat of the wall, and adding an actual layer of modern insulation. It would also mean having to find somewhere else to live for the foreseeable future. And so, we find other ways of getting comfortable, or, at least, minimizing discomfort.

There is a vast submarket of products that claim to help people stay warm in the winter without raising their heating bill. Some are better than others. Some, like a space heater (of which we have two), merely redistribute the cost from the gas bill to the electricity bill. Others, such as heated socks, are products of desperation. Most of them are, frankly, bad. All of them have made me consider the broader role of technology as it relates to climate in architecture at the domestic level, and at the level of the human body. These technologies are broadly separated into two categories: wearable and non-wearable. All of them were purchased from Amazon.com.

The first line of defense against a cold house is putting on more clothes. Anyone who’s had a parsimonious father knows the saying, “if it’s cold, put a sweater on.” In my case, it’s putting on a fleece-lined pair of leggings and undershirt.2 This is the cheapest option. (Cost: $32.99/pair for the leggings, $18.99/fleece lined undershirt.) One would think that this is the most sustainable one as well, until one finds out that almost all fleece-lined anything is polyester, which is to say, made of oil and shipped from China. And so, one burns oil to compensate for the lack of oil. The purpose of the liners is to keep air close to the body. Later, I would wise up and add a wearable blanket ($19.99, also polyester) over my clothes to greater effect—however unattractive and unpresentable to house guests.3 This works quite well for the core and for the legs. But the extremities immediately become numb.

Product name: Heated Socks for Men Women, Battery Heated Socks, Electric Heating Socks for Men Women Camping Fishing Cycling Skiing Skating Hunting Hiking. Available on Amazon.

People think wearable technology is some kind of sexy, unique concept involving VR headsets and the blockchain. For all the hype about wearables, let me offer a distinctly terrible counter-example: heated socks. Socks with little electric coils on them! What a brilliant idea! This sounds like a fantasy, speaking as someone with Raynaud’s syndrome, which makes my feet exceptionally prone to cold.4 The second I learned of heated socks, I bought a pair ($30), eagerly awaiting a new life beyond the immobilizing pain of constantly cold feet.5 There are numerous forms of heated socks, none of which are good. Heat actually requires, well, a power source. The most common power source of heated socks is batteries. Sometimes, these are rechargeable, but a charge only lasts for two or so hours, much less if you wear them outside and have to jack up the power. The first socks I bought were powered by regular batteries. When six AAs didn’t even last me an entire day of warmth, I deemed the sock project a failure. Feet are constantly in contact with cold surfaces, like the floor or shoes, and heating them is like trying to catch a thunderstorm in a bucket.

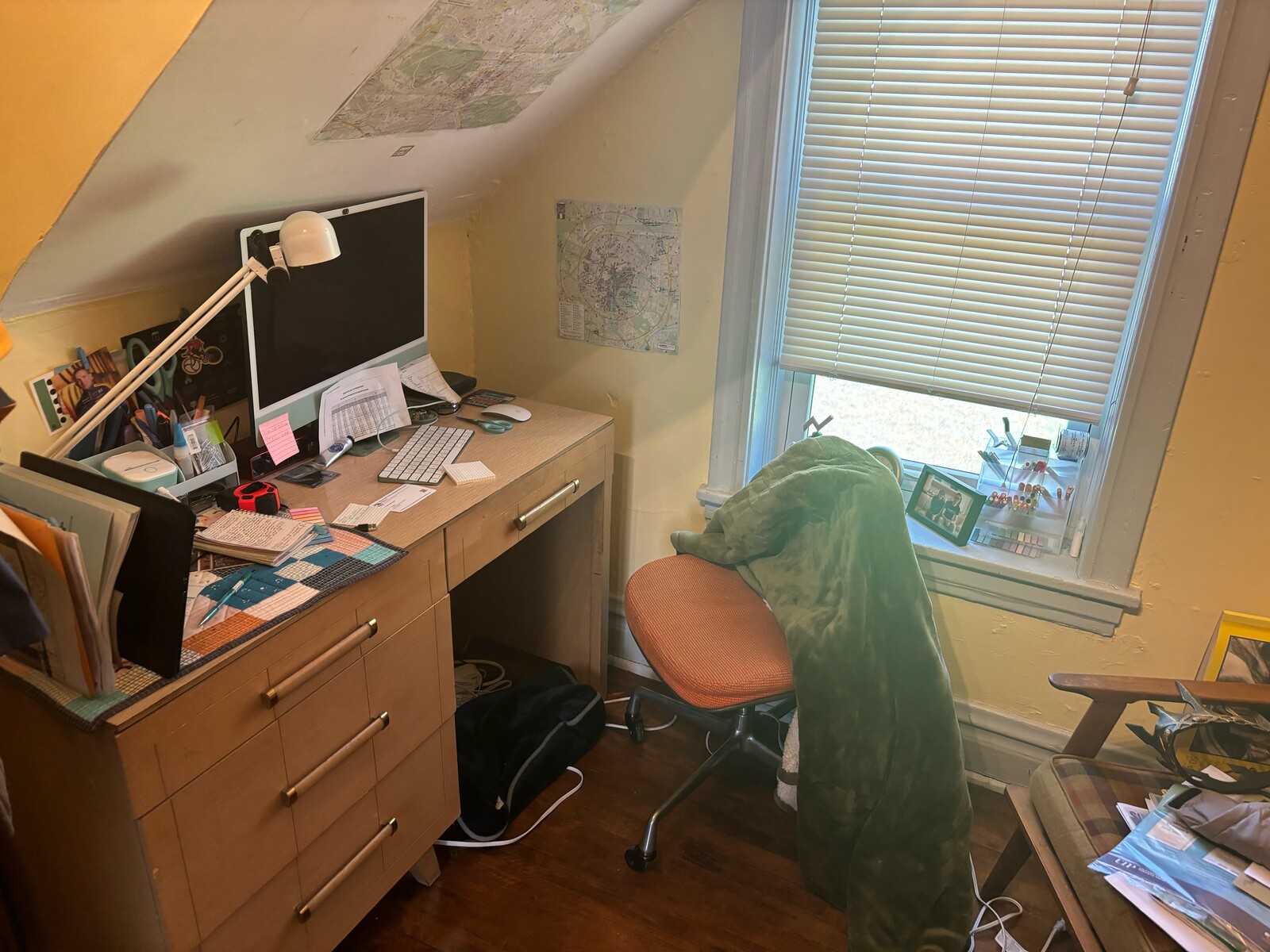

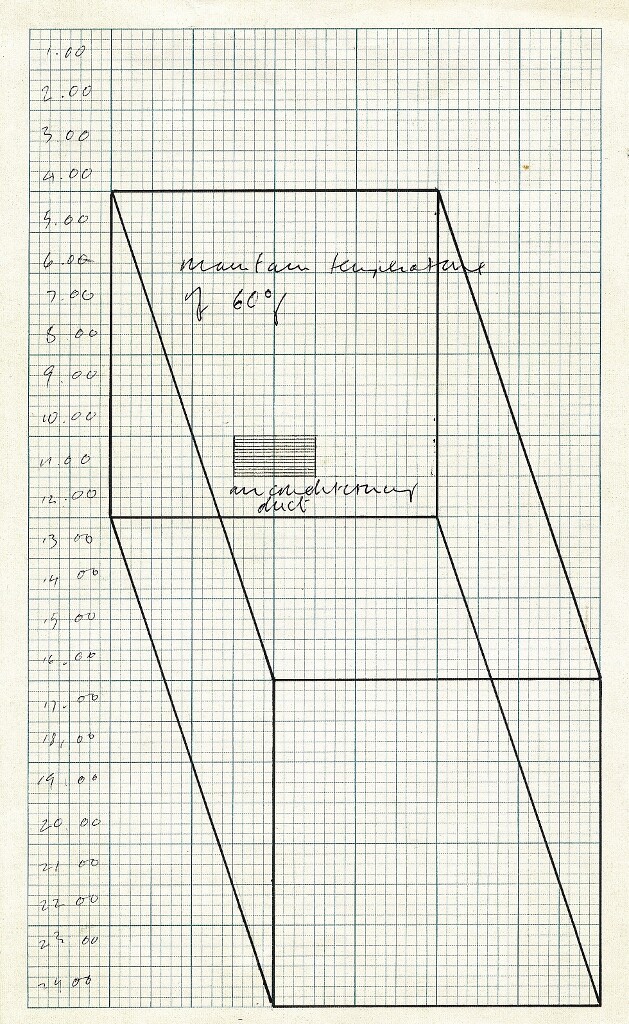

The street-facing wall of my home office is uninsulated because it is located under the stairs. It is the coldest room in the house by far. There, additional measures have to be taken beyond clothing, yet they still remain embodied. Consider them the remit of “half-wearable” technology, an academic euphemism for heated cloth. These come in two forms, both of which are still much more energy-efficient than something like a space heater. Perhaps one of the most effective combatants of a cold house is the electric blanket ($36) and its cousin, the electric foot warmer ($30), which sits under my desk.6 The electric foot warmer is a great psychological trick. By surrounding and insulating the extremities from the floor (using, you guessed it, polyester), the whole body feels warmer as a result. However, the electric blanket is the most useful way of getting warm quickly.

Often during this past winter, I would be working in my office trying to tough out the temperature, but even with my ugly non-outfit of layers, I would become so cold that I needed to take reprieve in my bed, with the duvet and the electric blanket, and recharge my body’s warmth for about thirty minutes. For those thirty minutes, I would be overwhelmed by the thought of how much I hate architecture, and of how unready architecture is for anything resembling a climate crisis. I would think about how, if the heat and the electricity went out—if everyone in the city’s heat went out—we would die. We would simply die in that house. The heat would evacuate so quickly that frost would appear on the plaster walls within the hour. But then I would become warm again and these thoughts would dissipate, would return to the place where the self-conscious deems the rational hyperbole.

Product name: Ceramic Space Heater for Indoor Use, Overheat Protection, Tip-Over Protection, Low Noise Heating, Safe Electric PTC Portable Fan for Office Home Room, Black Smart Handy Warmer for Bedroom Desktop. Available on Amazon.

This leads us into non-wearable technologies. By February, when outdoor temperatures reached -7 degrees Fahrenheit, I reached a point of such desperation with my office that I had to buy a little space heater. The office is tiny—not big enough to be a real bedroom, only about 8x8 feet—so I bought the smallest space heater I could find. (Because I am design-oriented, I got the one that looks the most like a Dyson; $25.)7 I resent somewhat how well the space heater works. I had spent every previous winter in this apartment (this is my fourth) refusing to use a space heater because they are extremely dangerous and use a lot of electricity. They are, so to speak, the coal-fired stove of contemporary cheap heating solutions. They work stupidly, as big versions of the same technology that makes up the electric blanket: heated metal coils. It wheezes by way of an incompetent little fan. Space heaters are correctives to rooms that should be better. Better insulated, better laid-out, better heated using their existing radiators. They are naked electricity suckers. When I owned one in Baltimore, the lights would flicker every time I turned it on. But this past winter, I didn’t care. I was willing to risk total combustion of everything around me to be a little warmer, and, in this way, I became a small metaphor for a greater human crisis.

The space heater, however, can be helped a bit, its use reduced from the constant to the periodical, through soft solutions (literally soft). The most effective is a door draft stopper ($15), which keeps heat from escaping from the gap between the door and the floor.8 It is made of polyester and polystyrene. The other solution is velvet curtains ($27), which are made of…9 The velvet curtains made the house so dark we had to keep the lights on during the day. I first tried them out when my husband was away and hated them so much I decided I would rather be cold and see the sun, which never came out anyway. By this point, the winter was easing its harshness. The foot warmer became enough. The frost stopped appearing as a thin glaze on the inside of my window. The space heater was turned off and put back into the closet.

All of this may seem funny, a long, seasonal mishap. But the desperation I felt trying to stay warm in a house that fought tooth and nail against me materialized in real tears, in frequent trips to go sit on the radiator or under the blanket, in violent shivering and teeth so clenched my jaw would hurt by the end of the day. In the end, the only real solution is either gutting the house or burning fossils fuels to jack up the heat ($300/month) only for it to disappear right back out of the shitty-landlord-special vinyl windows.

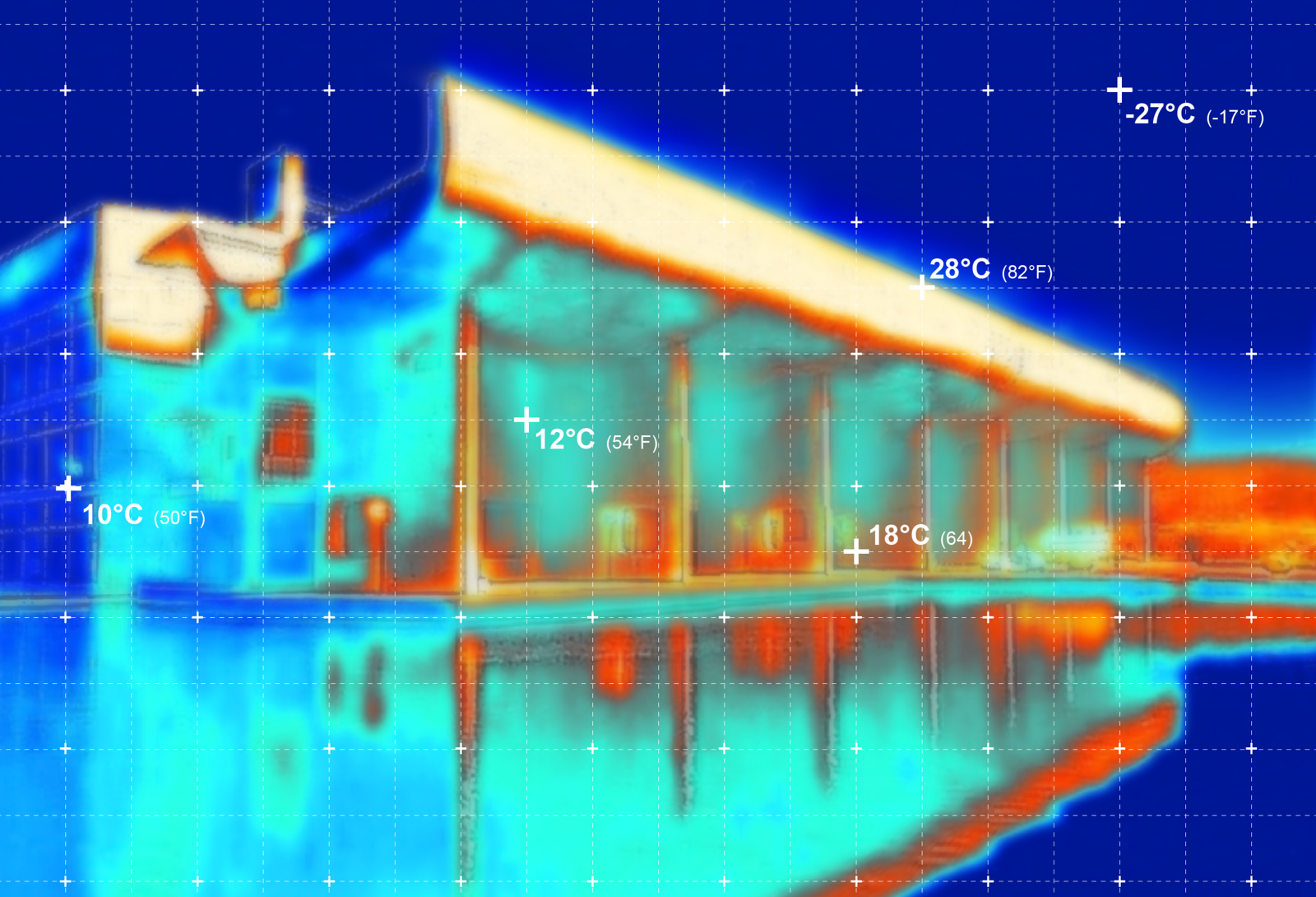

People ask me all the time what architecture can do to mitigate climate change, which will only make abnormal weather events like extreme cold more likely, despite the generally rising temperature. Meanwhile, day after day, architects continue to propose floating cities and green roofs and green walls that are half dead in a year, and create hundreds of renderings for theoretical projects that do not interrogate the things that need interrogating (namely anything related to technology, which is seen as the final and only savior at the last minute). Every time I’m asked, I want to scream: none of this will be sexy. None of it will look like a tropical paradise serviced by flower-petaled solar farms. It will look, at least I hope, like insulation.

A great book on the topic is Emily Thompson’s The Soundscape of Modernity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004).

“Catalonia Wearable Blanket with Sleeves and Pocket, Cozy Soft Fleece Mink Micro Plush Wrap Throws Blanket Robe for Women and Men, Gift for Her,” Amazon, ➝.

“Raynaud’s Disease,” Mayo Clinic, ➝.

“Heated Socks for Men Women, Battery Heated Socks, Electric Heating Socks for Men Women Camping Fishing Cycling Skiing Skating Hunting Hiking,” Amazon, ➝.

“Homemate Heated Blanket Electric Throw - 50”x60” Heating Blanket Throw 1/2/4/6/8 Hours Auto-off 10 Heat Level Heat Blanket Over-heat Protection Flannel Sherpa Heater Blanket Electric ETL Certification,” Amazon, ➝; “Double Sided Electric Foot Warmer with LCD Display & Machine Washable, Electric Feet Heating Pad with Non-Slip for Under Desk,Bed,Office,Home,Navy,20”*20”,” Amazon, ➝.

“Ceramic Space Heater for Indoor Use, Overheat Protection, Tip-Over Protection, Low Noise Heating, Safe Electric PTC Portable Fan for Office Home Room, Black Smart Handy Warmer for Bedroom Desktop,” Amazon, ➝.

“Holikme Door Draft Stopper Door Sweep Weather Stripping Noise Blocker Window Breeze Blocker Adjustable Door Sweeps, Grey,” Amazon, ➝.

“Velvet Heavyweight Pinch Pleat Curtain Panel Pair, 63” Length, Teal,” Amazon, ➝.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.