“The purpose of the home is to keep inside inside and the outside outside,” writes Jonathan Hill, implying a deep, psychological layering of what is understood to belong with us in our interiors.1 To “keep” is not a static gesture but rather a constant metabolic negotiation. For as long as people have built homes, they have also had to consider issues such as how to retain the warmth of the fire inside while effectively disposing of its smoke, or how to fend off the burning rays of the sun while maintaining a flow of fresh air indoors. Buildings contain air, but that air is never constant. As Nerea Calvillo writes, “The air is moving architecture, exchanged with the exterior and managed through ventilation, heating, and breathing,” hinting at the technological, cultural, and biological factors affecting indoor environments, as well as the inherent leakiness and interdependence that characterizes the porous boundary between inside and outside.2

And yet, the proliferation of knowledge about urban air pollution, as well as the popular assumption of the individuality and safety of the home, has resulted in the belief that the indoors is a safe space, which can be sealed and made immune to devastating environmental pollution outside. The history of drying laundry in the city complicates this notion, posing laundry practices and people living in buildings as leaky, moist subjects. Beyond revealing issues of overcrowded, damp housing, internal air pollution, and practices of comfort and cleanliness, with their associated energy consumption implications, laundry histories are also a way to amplify critiques of sustainable technofixes and sealed environments.3

Hawkins electric clothes dryer, UK, 1958. Credit: Alamy.

In the UK, where housing (particularly in the rental sector) faces widespread issues of damp and mold, condensation guides are commonly distributed to tenants by landlords and management organizations to instruct them on how to produce less moisture.4 The implication of these guides is that residents are responsible for the proliferation of harmful damp and mold in their homes by misusing their flats or simply producing too much moisture. While some suggestions sound helpful, like “ensure your bathroom extractor fan works,” some slip into absurd, like “cover your pans while cooking or take shorter showers.” All reveal the indelible fact that daily life is an inherent source of moisture. Some of the guides remind residents that condensation is even formed at night, when they sleep and breathe. Working class bodies, with their leaky breath and humid labor of reproducing life, are to be curtailed and confined. The instructive brochures distributed to residents position them as mere moist inconveniences capable of causing damage to the landlord’s building. Much like the gendered shame of unruly fluids, here classed bodies are positioned as leaky, excessive, and threatening: their reproduction is to be managed, cut back, or at least contained.5

Drying laundry indoors is one of the most frequent culprits in condensation guides against the formation of damp and mold. Drying clothes inside is responsible for up to 30% of the humidity in indoor air. Yet residents frequently do not have other options.6 Either they do not have private outdoor space, are forbidden from hanging their washing outdoors, or cannot afford the costs of buying and operating a tumble dryer, especially as energy prices rise in Britain. What condensation guides do not mention is that indoor drying has detrimental effects not just on buildings, but also on internal air quality and human health, through the emission of hazardous carcinogenic chemicals from fabric softeners, the production of dust mites, and the high mold-spore counts that contribute to respiratory conditions and eczema.7 These issues are further compounded in homes that are poorly ventilated and overcrowded.

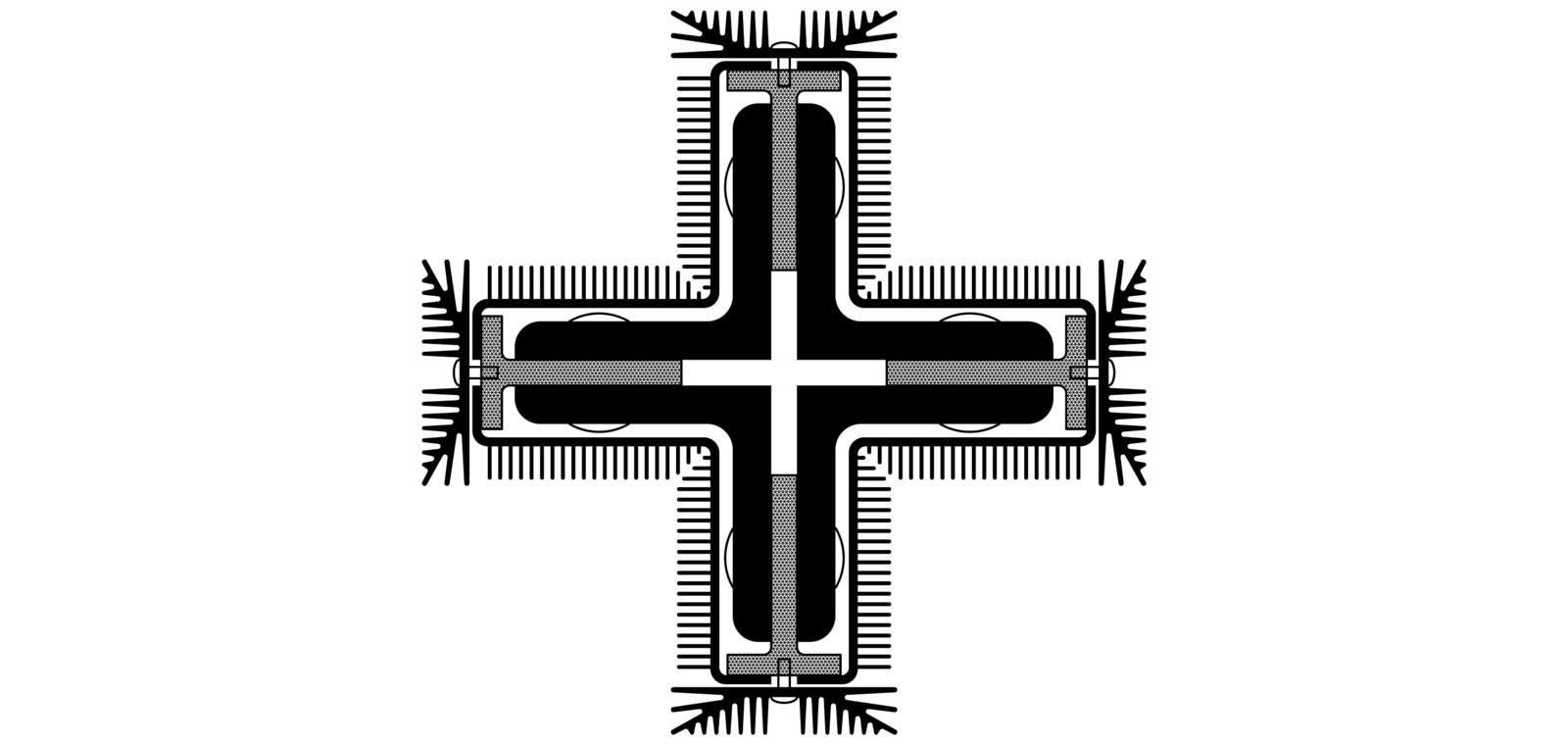

Plan of proposed baths and public laundry, Finsbury, London. Source: Alfred W. S. Cross, Public Baths and Wash-Houses (1906).

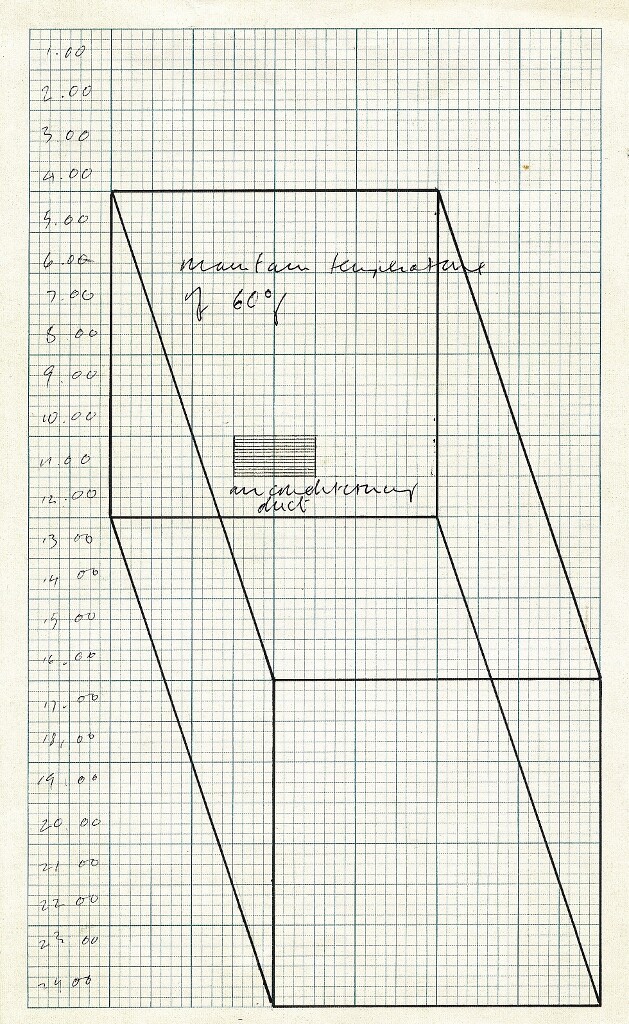

The detrimental impact of air-drying laundry on the internal environment was identified as early as the mid-nineteenth century, when overcrowding and squalid housing conditions pushed the British government to introduce legislation that would prevent further waves of epidemics. The Baths and Washhouses Act was introduced in 1846 to enable local authorities to build public baths and laundries, motivated in part by the need to alleviate unhealthy indoor environments caused by air-drying laundry indoors.8 As a result, the moisture-producing labor of laundry was deemed not to belong in the private home, and was brought out into the public sphere, to purpose-built civic buildings where women from different households worked side by side. Laundry has since largely transitioned back to the private home, with commercial launderettes and communal laundry rooms forming an intermediary stage of this history.9 In 1976, there were about 1,000 laundry and drying rooms on social housing estates in London; almost none are left today.10

The postwar explosion in access to private property and consumerism, as well as the boom in the domestic appliance market, propelled the individualization of laundry in the West. Tumble dryer advertisements from the 1950s and 1960s sold not only the myth of the end to domestic drudgery, but also promised complete control over one’s environment, independence from unpredictable elements and from the weather outside. All this for just the price of a new appliance and a steady consumption of electricity. The tumble dryer discreetly confined laundry, and its moisture, to a neatly sized domestic machine. As Dianne Harris writes, in the postwar American suburbs, it became a status symbol to own one and, consequently, the sight of outdoor washing lines became associated with lower-class living and non-white identities.11 The tumble dryer has remained a mainstay of domestic laundry routines in the USA, cementing specific notions of comfort and cleanliness associated with the appliance, and upholding the taboo status of outdoor drying. Some homeowner associations’ strict rules still ban washing lines outside.12

A similar gesture of commodification and privatization was undertaken during the 2023 refurbishment of the modernist landmark and social housing icon, the Balfron Tower in London. Designed in 1963 by architect Ernő Goldfinger for the London County Council, the building exemplified the optimism and social agenda of the time. In addition to shared music rooms, hobby rooms, and sports rooms, the twenty-six-story tower contained several communal drying rooms for laundry, located in the service tower. During the refurbishment, which transformed the building into luxury housing, the drying rooms, as well as other shared amenities, were turned into spaces of leisure, including a yoga room, library, private dining room, and cinema. The change of use of the drying rooms speaks to the transition from utility to trophy apartments, and highlights the ways in which the original design’s socially-minded ethos was appropriated.13

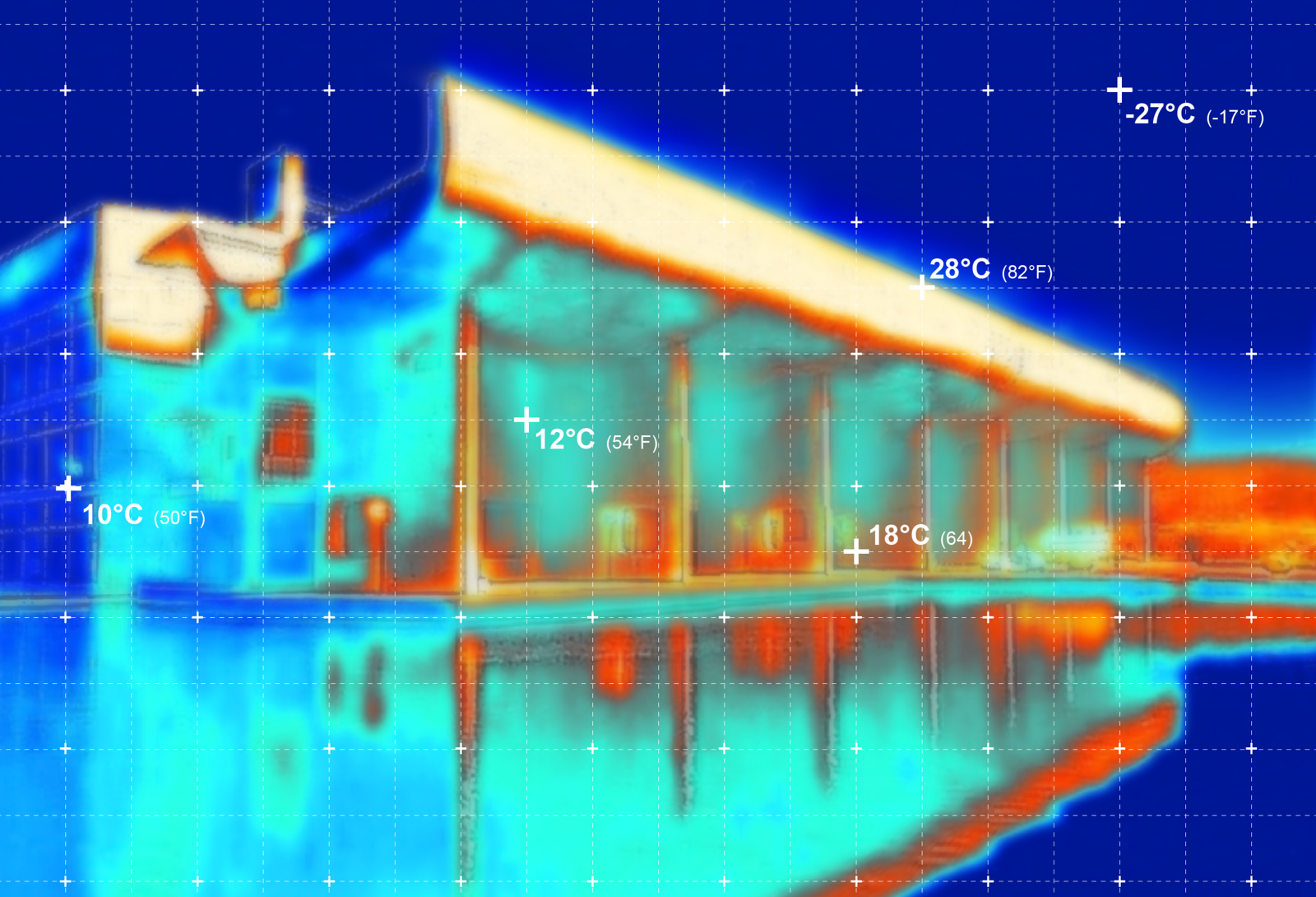

These transformations were accompanied by sealing windows on the building’s east elevation, which faces the busy A12 highway. This was done to reduce acoustic and air pollution, but it also obstructs cross ventilation through the building.14 The turn away from communal provision for drying, and the simultaneous closing of the apartments, cemented the private interior as a discreet “sealed environment.”15 At the Balfron Tower, with the technological help of mechanical ventilation and tumble dryers, flats became, in the words of Peter Sloterdijk, independent “pieces of enclosed air”: simultaneously protecting residents from traffic fumes and trapping them with the less spoken of effects of internal air pollution.16 The refusal of the communal provision of laundry facilities for the sake of an individual solution in each flat, reliant on more sophisticated mechanical ventilation systems, aligns with Sloterdijk’s critique of the apartment as a fully self-sufficient, isolated, metabolic unit, devised for the cultivation of the individual’s relationship to themself. Here, a parallel appears between the individualism of modern society and the apartment’s seemingly discreet separateness and independence. Confining moisture-producing domestic routines to the privately-filtered individual home is a short-term fix against long-term challenges (such as urban traffic pollution), especially considering that the key to good internal air quality is the rate of exchange with outdoor air.17

Much like how tumble dryers came to signify notions of cleanliness and comfort in North America, line-dried washing epitomizes the desirable scent and feel of freshness in many other parts of the world. In Singapore, flats built in the government’s large-scale resettlement scheme starting in the 1960s were small but came with external pole-and-socket system for drying clothes. Still today, rows of spiky laundry poles loaded with washing extend even to the highest floors of multi-story residential blocks. However, private developments and recent aspirational public housing projects employ a more conservative approach to drying, incorporating screened “service yards” and banning laundry racks on balconies.18 But the attachment to line-hung laundry is so strong that the market responded with an appliance that mimics external conditions within the confines of the home. The so-called “indoor automated drying system” is the bewildering love child of the washing pole and air-conditioning. Designed to be installed indoors, this high-tech washing line uses electricity to produce heat and breeze to dry washing. The process of drying can now be frictionless and controlled—there is no need to hang laundry outside nor to take it back inside in case of rain. In a country that relies on air-conditioning to fend off constant equatorial heat and humidity, power-generated heat and artificial UV rays to dry clothes indoors epitomize the deep paradoxes in domestic energy regimes.

In the words of Emma Pask, “[it] is embarrassing to leak,” and yet we must.19 Writing about the understanding of bodies as bounded units, Pask invokes the sexed shame that still surrounds public menstruation or lactation. Through dirty laundry’s close association with the sexed body, its fluids, and reproduction, clothes drying outside and in the public view have long been stigmatized and coded as embarrassing in the West.20 Sustainable technofixes driving much contemporary architecture today advocate against leaks too, through the construction of increasingly airtight building envelopes and carefully controlled mechanical ventilation systems. The green transition in the built environment is often presented through the lens of the household employing the latest technologies to solve issues and lower bills on an individual scale. But as mounting housing and health crises show, the management of moisture and pollution in the home is an urban, legislative, and infrastructural challenge. Taking the labor of laundry out of the private home and into the public realm can therefore be part of a wider cultural shift to address the deadlocks and interdependencies in the current era of environmental breakdown and of reliance on constant, individualized comfort. There is only so much moisture a single home can contain, or reasonably process. Humans and buildings alike are moist, porous subjects. We should seriously consider once again airing our laundry in public.

Jonathan Hill, Immaterial Architecture (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2006): 8, with thanks to Eliot Haworth, whose work on porosity and anthropod life at Couvent Sainte Marie de La Tourette first alerted me to this quote and text.

Nerea Calvillo, Aeropolis: Queering Air in Toxicpolluted Worlds (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2023): 24.

Elizabeth Shove emphasises that “people do not consume energy, water or gas. Instead, units of consumption and change relate to the specification and reproduction of normal conventions like those of comfort, copresence or cleanliness.” She thus argues that a transition to a more sustainable society does not only include cutting down energy use but also necessitates a deep understanding of the conditions of everyday life and how notions of safety, comfort, and cleanliness are constructed and reproduced. Elizabeth Shove, “Sustainability, System Innovation and the Laundry,” in System Innovation and the Transition to Sustainability: Theory, Evidence and Policy, ed. Boelie Elzen, Frank W. Geels, and Kenneth Green (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2004): 88; Calvillo writes “Sustainable techno fixes aim to ‘solve’ pollution problems through technology, leaving its social attachments and impacts unattended. While surely this kind of solutionism can temporarily alleviate local issues—crucial in contexts of lethal exposure—it often contributes to the problem” (Aeropolis, 27-28); see also Daniel A. Barber, Modern Architecture and Climate: Design before Air Conditioning (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020).

The death of toddler Awaab Ishak in 2020 was ruled by the coroner to be caused by chronic exposure to mold in his home and associated respiratory issues. “Awaab’s Law,” which would introduce strict time limits for repairs on landlords is currently undergoing consultation. George Lythgoe, and Rumeana Jahangir, “AWAAB’s Law: Rochdale Mouldy Homes Tenants ‘Told They Breathed Too Much,’” BBC News, January 14, 2024, see ➝.

feminist architecture collaborative, “The Incubator Incubator, the Administration of Leaky Bodies, and Other Labor Pains,” Harvard Design Magazine no. 46 (2018): 147-153.

Rosalie Menon and Colin Porteous, “Design Guide: Healthy Low Energy Home Laundering” (Mackintosh Environmental Architecture Research Unit, 2011).

Menon and Porteous, “Design Guide.”

“Baths and washhouses,” UK Parliament, see ➝.

For more about launderettes, see Edwina Attlee, Strayed Homes: Cultural Histories of the Domestic in Public (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2022).

More on the 1976 closure of laundry and drying rooms and the urban washing line can be found in Marianna Janowicz, “Where There Is Life, There Is Laundry: The urbanism of the washing line,” Islands, ed. George Kafka and Lila Boschet (London: Design Museum, 2023): 44-50. See ➝.

Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Though this is illegal in many states. See ➝.

David Roberts, “Make Public: Performing Public Housing in Erno Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower,” The Journal of Architecture 22, no. 1 (2 January 2017): 123-50.

Olly Wainwright, “‘The Council Tenants Weren’t Going to Be Allowed Back’: How Britain’s ‘ugliest Building’ Was Gentrified,” The Guardian, July 26, 2022, see ➝.

Barber, Modern Architecture and Climate.

Indoor air pollution is reported to be 3.5 times as high as air pollution outside. “Indoor Air Pollution 3.5 Times Worse than Outdoor Air Pollution,” Global Action Plan, ➝; Peter Sloterdijk and Daniela Fabricius, “Cell Block, Egospheres, Self-Container,” Log no. 10 (2007): 89-108.

Rachael Wakefield-Rann, Dena Fam, and Susan Stewart, “Routine Exposure: Social Practices and Environmental Health Risks in the Home,” Social Theory & Health 18, no. 4 (December 2020): 299-316.

Jennifer Polland, “Singapore’s New Public Housing Project Looks a Lot like a Luxury Condo,” Business Insider, April 3, 2013. See ➝.

Emma Pask, “Becoming a Leak” The New Inquiry, May 30, 2017, see ➝.

For more on laundry’s close association to the sexual female body and related spatial marginalisation, see Diane Ghirardo, “Women and Space in a Renaissance Italian City,” in Intersections: Architectural Histories and Critical Theories, ed. Iain Borden and Jane Rendell (London: Routledge, 2000). See also Aritha Van Herk, “Cleansing Dislocation: To Make Life, Do Laundry,” in The Domestic Space Reader, ed. Kathy Mezei and Chiara Briganti (Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 2012), 194–187.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.