Kwabena Appeaning Addo: What inspired your design for the Inno-native House in Accra, Ghana?

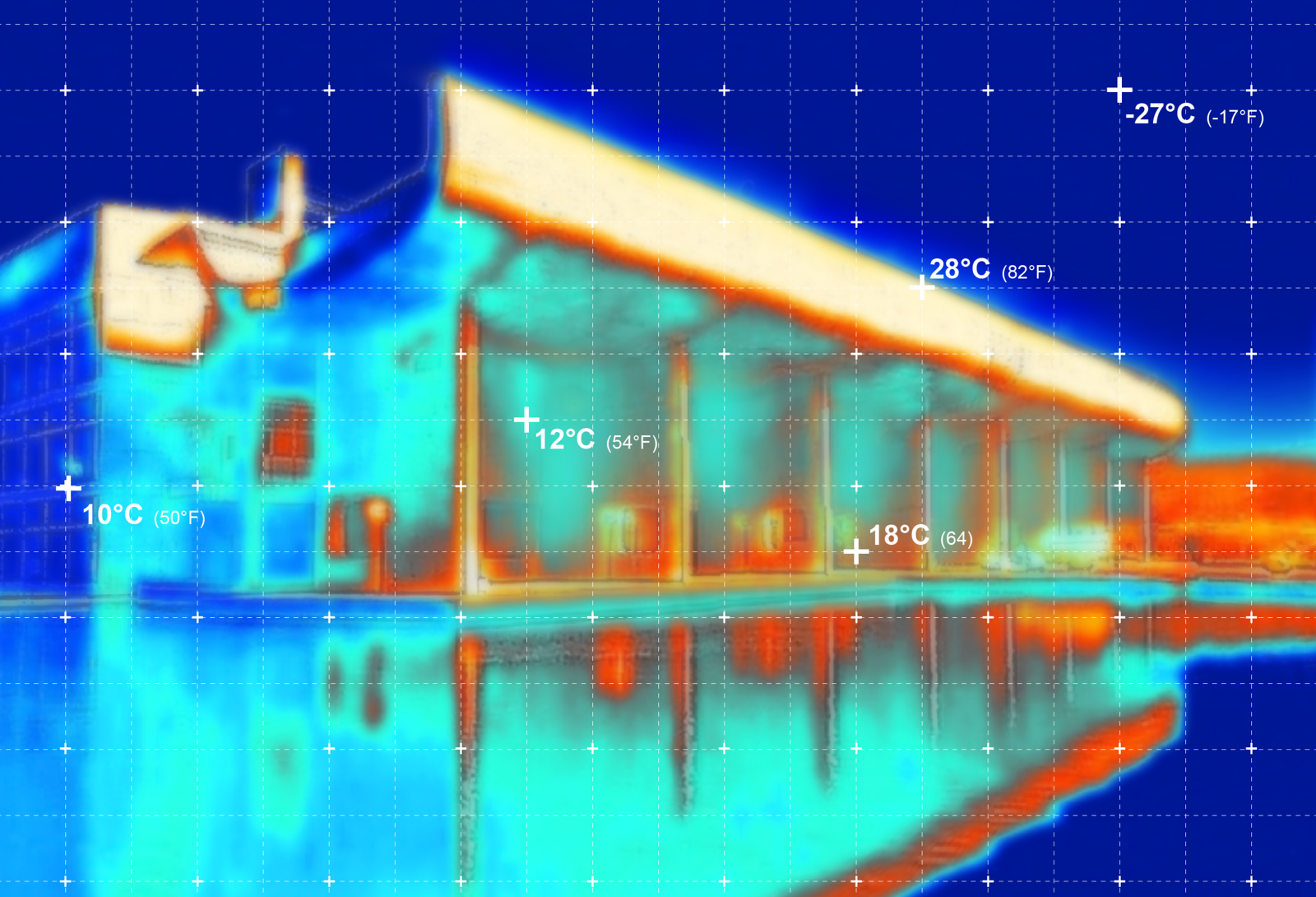

Joe Osae-Addo: My first thought was “How do I create a building that responds to the weather better than most,” so that I don’t have to use air conditioning? That was my primary focus. I then began thinking about the landscape, about how trees can be used as the first line of defense against heat, and also about how to position a building so that there is no direct solar gain. I was working in Los Angeles at the time, and I learned that the worst heat comes not from the sun, but through conduction from the earth, through the floor slab. So I thought to raise the building by about a meter, removing all direct contact between the floors and the earth, and insulating the building with a pocket of air. Those were my design parameters.

KAA: What happened when you took those principles onto the building site?

JOA: The site and the climate drove the initial layout of the building. After pouring the raised foundation, the first thing I did was to plant mature trees. I didn’t want to plant seedlings, because I wanted the trees to cover the roof by the time construction was done. So, I took a drive out of Accra to the area between Tema and Shai Hills, where there is a natural forest of trees. I went on a rainy day when the soil was wet, with a truck and laborers, and dug out mature—but not fully grown—trees, approximately three meters tall. We brought them back and planted them immediately. A year later, when the house was done, the trees had fully grown in. The ground also had a high water table, so I planted papyrus plants, knowing that they would suck up water. But even so, the site is very wet. On a rainy day, the concrete walkway in front of the house gets wet both from above and below. For the driveway, I used gravel, not concrete, to allow water to flow through and absorb into the ground when it rains. The landscape was integral to the design from the beginning. It is what allowed me to create a cool building.

KAA: What about in the design of the building itself?

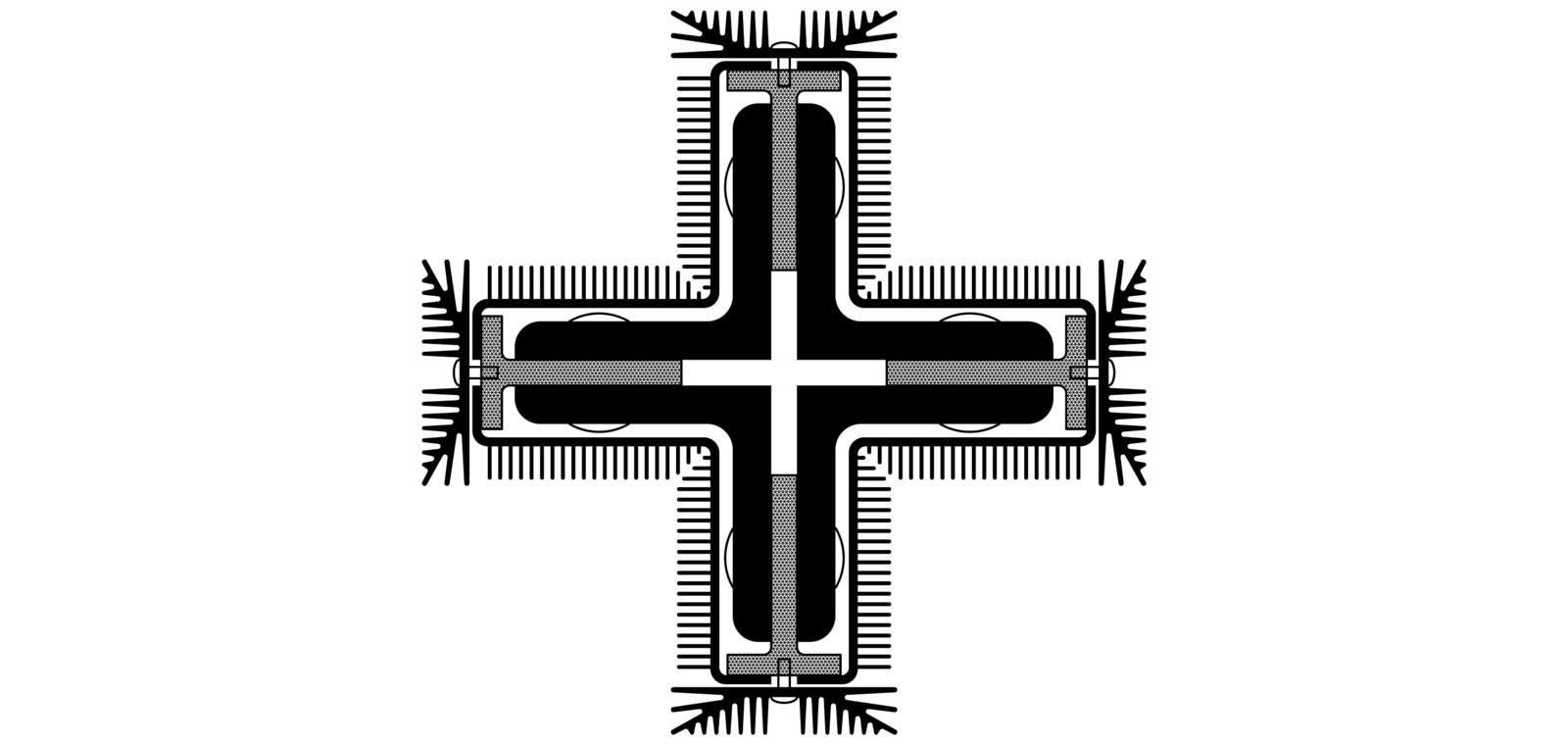

JOA: Glass louvres are typically undervalued in contemporary Ghanaian architecture, but they are fantastic at creating cross-ventilation. Many of the exterior walls include glass louvers, at times from floor to ceiling. The rest are made either of laterite blocks or of timber frame walls joined with a tongue and groove system. The interiors of these wood walls are covered with stucco plaster, which makes it feels like a typical cement block wall, but on the outside it is clearly wood. This construction technique, known as Type V construction, is how most buildings in California are built: a 2x4 timber stud frame, 24 inches on center. In my case, however, since there is no air conditioning, there is no need for insulation. The third type of wall in the house, which I am very proud of, is made of wooden slats with a mosquito net attached. The wooden slats have a half-inch gap between them so that air can come through, but because of the net, insects can’t. The interiors are therefore always aerated.

KAA: So does it work?

JOA: Yes, it works! If we had air conditioning, the timber studs would let out so much cold. But because the diurnal temperature variation in Ghana is not significant, designing for cross ventilation works so much better.

KAA: Can you further explain how the walls were designed?

JOA: At the entrance, for example, there is a wall that looks like it is painted concrete block, but it’s actually just plastered. To do this, we placed half-inch plywood against the timber studs, and then placed chicken-wire mesh over the plywood as the support for the plaster.

KAA: So on the inside, it looks like a normal wall, but on the outside, it has a wooden finish. What is it like to maintain the house?

JOA: Well, I haven’t touched it in twenty years.

KAA: Really?

JOA: Well, there was some damage to the surface of the wood deck in the back, but that was because of poor detailing—I shouldn’t have used galvanized nails, which can rust and rot the wood. I haven’t had to repair any of the vertical surfaces.

KAA: That means that it must have been really well constructed.

JOA: Yes, it was. I built it myself, so I made sure everything was right.

KAA: It also means that the wood was treated very well.

JOA: At that time in Ghana, kiln-dried wood wasn’t available. All of the wood we used had to be air dried, so I picked the hardest wood available, which was called “Odanta,” or iron wood. It’s expensive, but I knew that maintenance would be a big issue if we did not use quality wood.

KAA: Does the fact that it doesn’t touch the ground also help?

JOA: Yes! Termites are often an issue if you use wood in Ghana, but this was solved by elevating the building off the ground.

KAA: At the Presbyterian Boys’ Secondary School I went to, some of the teachers’ bungalows were made of wood and they sat on the ground, so I can attest to this! Can you speak further about the laterite walls?

JOA: The laterite walls are composed of compressed earth blocks. I made the blocks myself with the standard cement block formwork. They are stacked and kept together using cement mortar joints, and then finished with stucco. To make the render, we filtered laterite through a sieve to get the finest particles, and added a bit of cement and water. After it dried, we applied clear masonry sealer to protect it from the rain. This generally works, but direct rain can still create damage. So I placed some vertical and horizontal wooden fins on the balcony, so that water does not hit the building directly.

KAA: Is there any benefit to using laterite blocks over sandcrete, which is more typical in Ghana?

JOA: I don’t know the physics of it, but sandcrete seems to conduct more heat than laterite.

KAA: In the middle of the living and dining space, the roof material changes to a translucent acrylic panel. Why is that?

JOA: I wanted to bring in some light. Most of the roof is made of long span corrugated metal, so it serves as a kind of skylight. I didn’t use Perspex because over time it would melt. This is about twenty-years old, and it’s still in perfect shape. Though it occasionally needs cleaning from above to make sure the light doesn’t get too blocked.

KAA: What about the floors?

JOA: The house has polished concrete floors. But the flooring is actually timber, because the house is raised. At the bottom is the timber frame, then, on top of that, plywood, then roofing felt, then chicken wire, and finally concrete, which is primarily made of quarry dust to get as smooth of a finish as possible.

KAA: I also noticed that the kitchen and dining room are lower than the rest of the spaces.

JOA: Yes, they are lower because I was following the topography of the site, which slopes downward. If they were kept at the same level, it would have been very inefficient. Besides, it makes for a nice transition from living room to dining area.

KAA: What about the spatial organization of the rooms?

JOA: Well, the house has no corridors. So you either move from room to room, or use the wraparound deck to avoid disturbing people in adjacent rooms. The reason for this is that when you have an interior corridor, it is difficult to maximize cross ventilation.

KAA: What were some of the challenges with the project?

JOA: Well, one challenge was finding the right carpenters. In Ghana, we don’t often use wood to construct buildings, so getting workers to understand the details and the drawings was difficult.

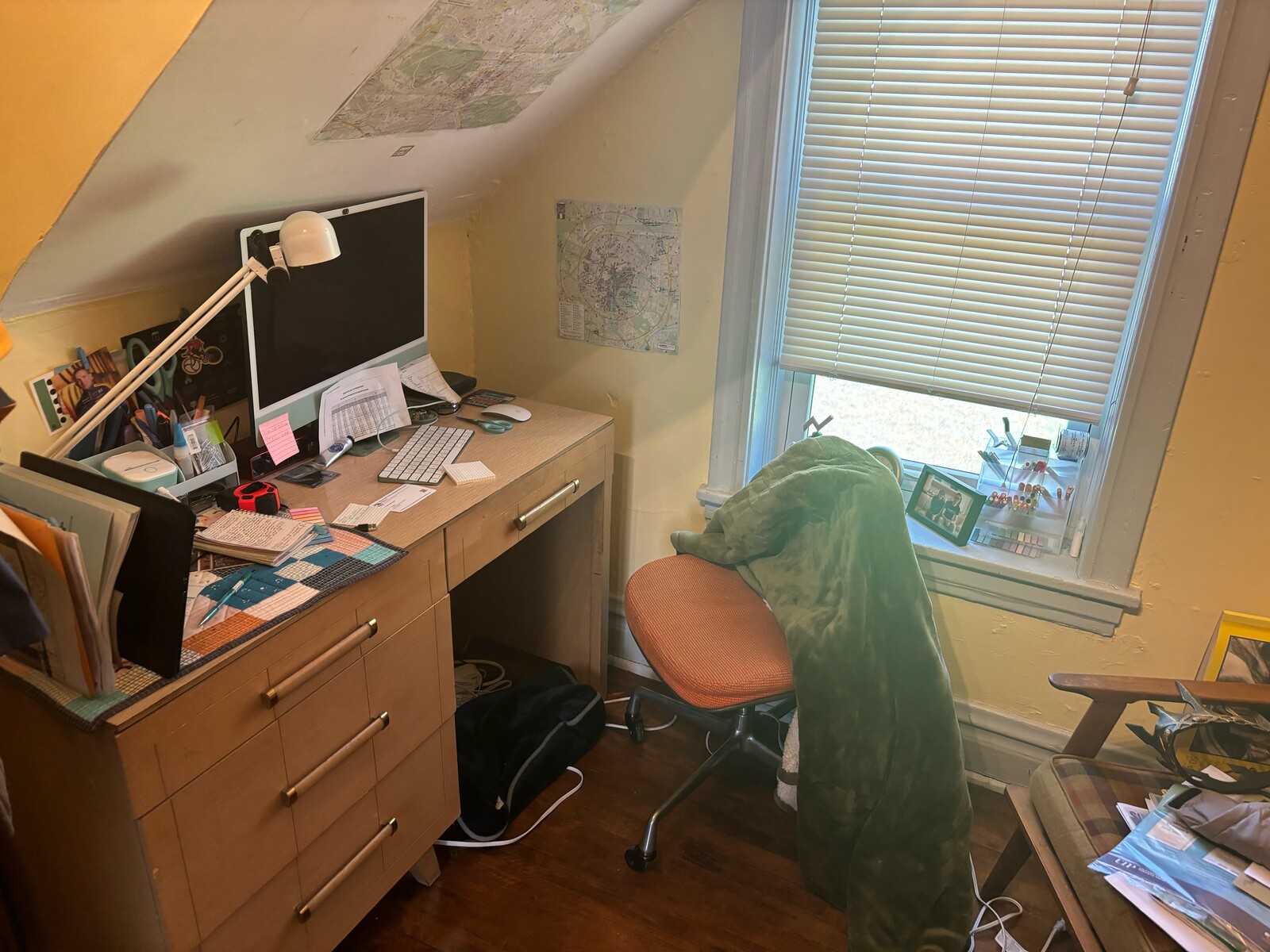

Inno-native House in Accra, Ghana. Photo by Kwabena Appeaning Addo.

Inno-native House in Accra, Ghana. Photo by Kwabena Appeaning Addo.

Inno-native House in Accra, Ghana. Photo by Kwabena Appeaning Addo.

Inno-native House in Accra, Ghana. Photo by Kwabena Appeaning Addo.

Inno-native House in Accra, Ghana. Photo by Kwabena Appeaning Addo.

KAA: How did you address this?

JOA: I wanted to complete everything in twelve months. Since the laborers and artisans were getting paid a daily rate, the longer the process lasted, the more I would have to pay. But since I was the contractor, I could set up systems to speed construction. After we built two bays of columns, for instance, the carpenters I hired to build the timber frames started prefabricating columns, so that we could erect them whenever we needed them. After a certain point, the process of construction became one of assembly.

KAA: Based on your experience, what advice would you give someone who wanted to create a similar design?

JOA: Designers need to make sure that they’re not putting materials in places where they’re going to be compromised very quickly. And, in general, the use of metal should be avoided. Rust is a big issue, particularly in coastal zones. The marine air is corrosive. I used louvres with plastic frames because the metal would have rusted by now. And if you use wood, after it rains, it should be cleaned. No matter how high quality the wood you use is, keeping it dry is best.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.