In Kampala, Uganda, several large shopping malls have been built and opened over the past decade. Fast-food restaurants, boutique shops, and chain-operated franchises are in rising demand by the expanding middle-income population. Within these malls, shops often occupy the space around the entrance, preventing sunlight from reaching deeper inside. These spaces then need to be illuminated by fluorescent lights, which produce glare. As glass-walled lifts go up and down through large atriums, air-conditioning units create a steady-state environment regardless of the season or climate.

Spaces around these malls are typically occupied by small stores and kiosks, which form improvised markets where people can shop and negotiate prices. Fruits and vegetables neatly displayed with price tags on chilled supermarket shelves stand in contrast to scenes of women with baskets on their heads, haggling and selling street food outdoors.

The rapid growth of Kampala’s urban population can be felt in the increasing traffic congestion during rush hours and the high volume of motorbike taxis zipping through the city at all hours of the day. Foreign capital can literally be seen flowing in through the ever-increasing number of shopping malls and luxury apartments. Construction sites usually feature rendered images with people shopping and eating at major fast-food restaurants, and display logos of major sports and fashion brands. These visualizations are meant to convey luxury, modernization, and contemporary Uganda. But in reality, this inflow of foreign capital has led to a standardization of services and building designs, resulting in a one-sided image of affluence.

It is within this context that the Yamasen Japanese Restaurant project commenced in 2015. The site is located on the outskirts of Kampala, specifically in a suburb known as Muyenga. The area is characterized by its tranquility, and is home to government officials’ residences as well as offices of international NGOs. Unlike the city center, the area is lush and green with many trees. That said, it has experienced significant change and commercial development over the last two decades. The restaurant’s site had been inherited from the landowner’s family; it was previously a place where local children would play football, weaving their passes among five trees of various sizes, all visible from the road.

One of the restaurant’s main goals was to re-evaluate the area’s climate and soil, and promote overlooked ingredients, materials, and techniques. We aimed to approach the architecture in the same way, which meant carefully observing and reinterpreting the environment, climate, way of life, spatial arrangements, and materialities that can be seen in Kampala.

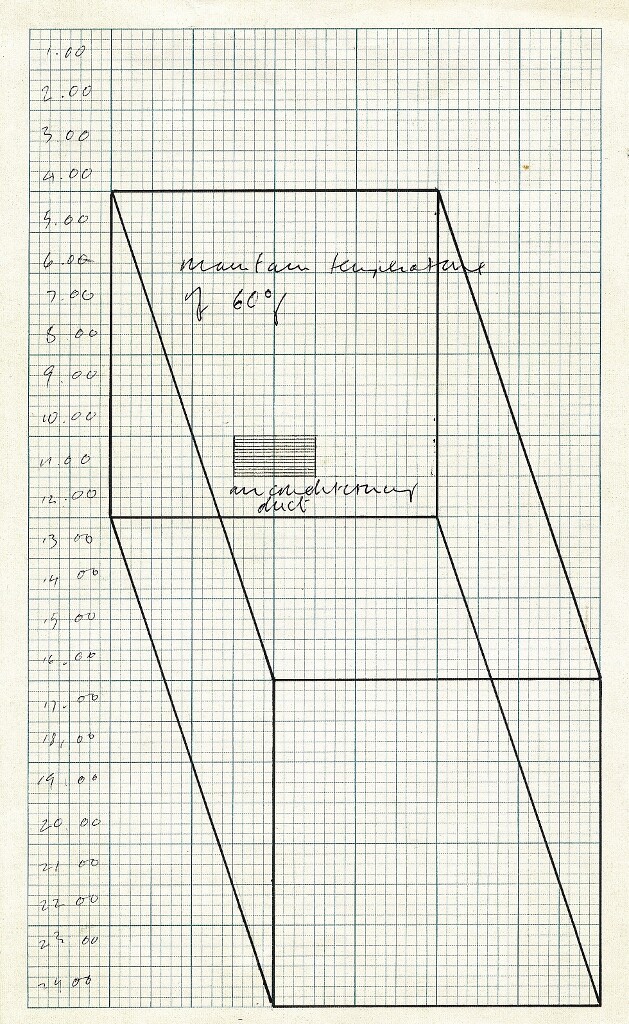

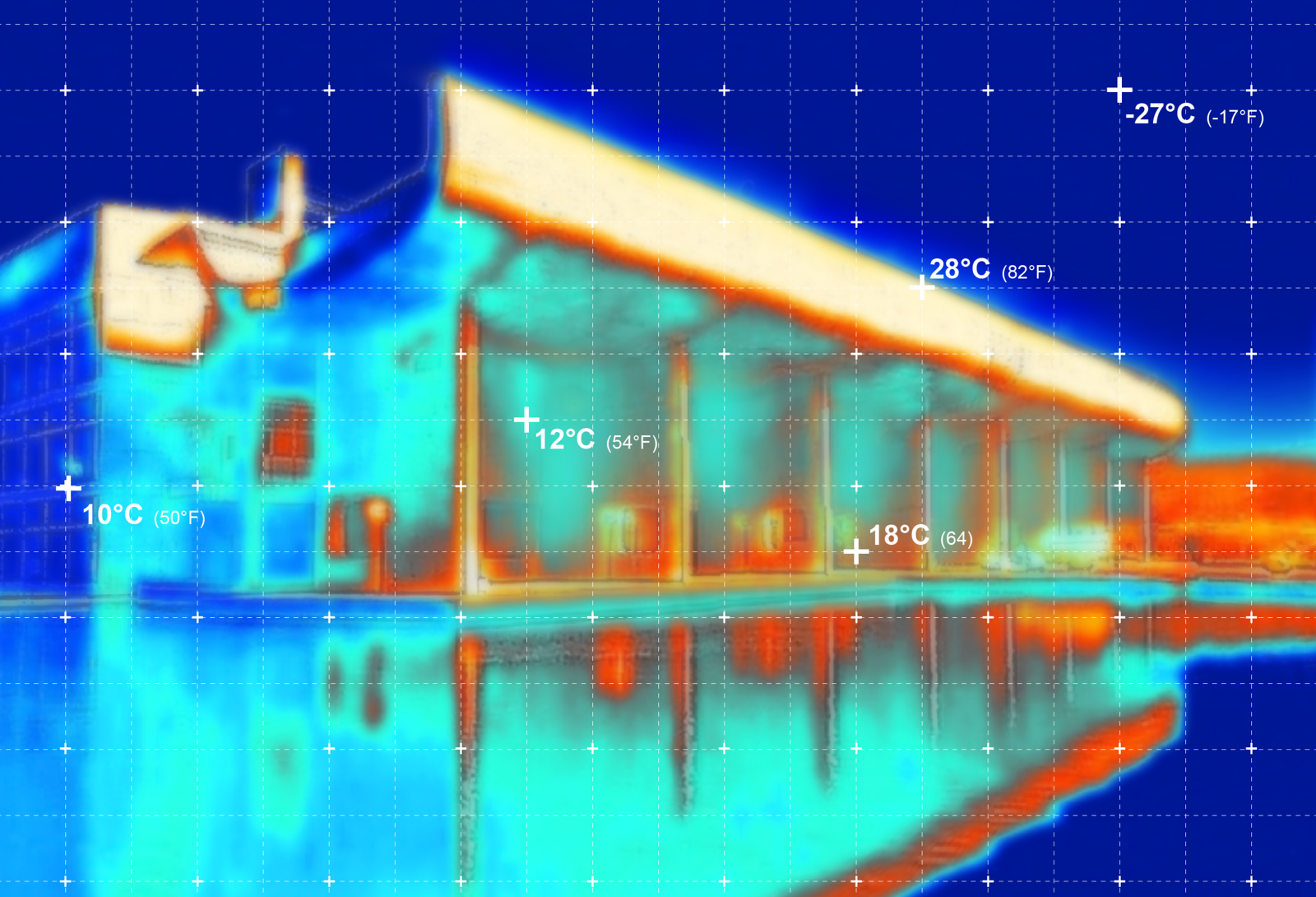

Kampala is located close to the equator, but due to its high altitude (about 1.2 kilometers above sea level), the average temperature is mostly below 30ºC, and rarely exceeds 35°C. The city is also subject to a north-south prevailing breeze, which is influenced by the rising and falling temperatures of Lake Victoria, the largest lake in Africa, located just five kilometers from the site. Rainfall varies widely with the seasons, ranging from 48 to 230 millimeters per month. The sunshine is strong enough to make one perspire when on the move, but sitting in the shade almost always brings a refreshing, cooling breeze.

In many urban areas of Uganda, houses lack proper lighting and ventilation, which prompts domestic activities such as cooking, washing dishes, or play to occur outdoors. Walking down an alleyway in Kampala, it is not unusual to come across women using sewing machines, and people playing games or sitting idly in chairs with bottles of beer or soda in their hands.

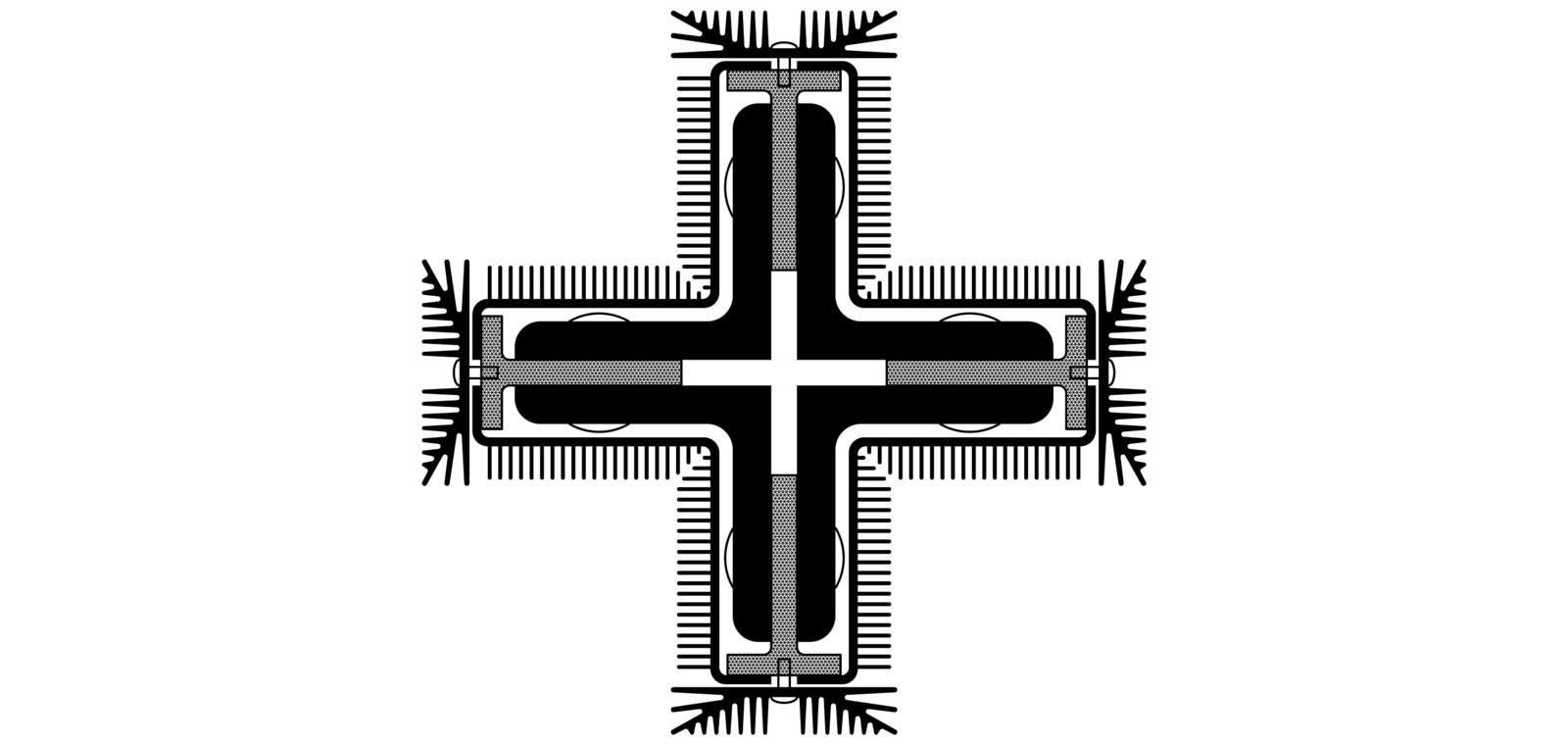

With the design of Yamasen Japanese Restaurant, we wanted to create an environment within which these kinds of scenes could take place. The architecture is comprised of a simple rectangular structure with a large roof that was subtracted from to protect the existing trees. Giving the building a north-south orientation was a way to take advantage of the steep topography of the site—a four-meter elevation difference—and give the impression that it emerges from the earth when viewed from the side.

A diverse range of spaces is included under the roof, including spaces with low eaves, spaces where the ceiling is so high that it’s almost unnoticeable, narrow and enclosed spaces that provide tranquility, and open spaces with wide views. Sunlight shines through the top of the roof and moves throughout the interior from sunrise to sunset, allowing visitors to likewise move through the space to avoid or seek out the light. Visitors can choose brightness or darkness, warmth or coolness, bustle or tranquility, grandiosity or intimacy, privacy or visibility.

A carpenter joining the main timber structure with steel plates that were welded on site. Photography by Timothy Latim.

The existing jackfruit tree defined the position of the terrace and provides both shade and fruit for the restaurant. Photography by Timothy Latim.

Open air café. The entire south facade is open to natural ventilation and lighting, allowing it to shift with the climate. Photography by Timothy Latim.

Interior; from north to south. To the right side of the image are the more private spaces, covered with an interior timber roof. To the left are the public spaces. Photograph by Timothy Latim.

Axonometric by TERRAIN architects.

A carpenter joining the main timber structure with steel plates that were welded on site. Photography by Timothy Latim.

Thatch, fired bricks, and eucalyptus are widely used as building materials in Uganda, but tend to be undervalued in comparison to imported materials such as aluminum cladding. For example, eucalyptus is a hardwood known for its strong propensity to warp, and is therefore primarily utilized for scaffolding and shoring. Eucalyptus is also known for its fast growth, and has been criticized for its potential to disrupt native forests in the area. It is a controversial material. However, it has become very common, even local, and therefore wanted to consider how to use it so it could last. By carefully selecting, drying, sawing, and milling, we were able to use eucalyptus wood for both structural purposes and finishing.

On top of sixteen large, exposed, structural wooden frames sits a thatched roof, which used thatch native to the northern part of the country and which was detailed and built according to the methods of local thatchers. The walls were boarded with half-sawn structural eucalyptus timber, and were also carefully formed with fired bricks made from local soil.

Alongside these organic materials, inorganic materials such as concrete, steel, and glass are readily available in Uganda, and an extensive community of artisans has developed around them. Our objective was not only to utilize local, organic materials wherever possible, but also to enhance their value by combining them with more inorganic and industrial materials. Concrete was used mainly for the substructure and in areas where it would otherwise be impossible to attain structural strength using other locally available material. The concrete floor is finished in a raw, natural state, and over time will undergo gradual wear. Steel was used as reinforcement, bracing, and, importantly, as a connection between the eucalyptus timber and concrete. These connections were made from steel found in local hardware shops and shaped by local artisans. The wooden frames were reinforced with round steel braces, and the posts were anchored to the concrete slab using rectangular steel sections welded to make a post, all locally fabricated. Glass is mainly used between the courtyard and the seating area and in parts of the café. Their eucalyptus frames protect against heavy rain and wind, and allow visitors to dine and shop while feeling the presence and changes taking place outside.

The clinical and controlled environments typically found in shopping malls in Kampala represent an extreme alternative to the unpredictable and chaotic environmental conditions prevalent in local markets and traditional homes. The growing use of inorganic materials can also be viewed as a response to the use of traditional organic materials, which often require much more frequent maintenance. As non-local architects, it’s easy to criticize the highly controlled, comfortable conditions and the excessive use of industrial materials in Kampala. However, we also recognize that this phenomenon is evolving into a cultural feature that cannot be simply dismissed or overlooked. The role of the architect, then, might be to carefully reinterpret what already exists and to express it anew through novel approaches. We must seek a balance between comfort and discomfort, rigidity and flexibility, steadiness and unsteadiness—not to disregard traditional culture, but also not to be overly nostalgic about it.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.