Heat and its experiences are dynamic: bodies, architecture, and infrastructure are entangled with varying political, socioeconomic, and ecological factors in their negotiations with heat and the politics of heat exposure. Heatscapes influence everyday navigations of heat and comfort for urban residents in chronically exposed and increasingly overheated cities of the Global South.

Within these urban contexts, infrastructural uncertainties and the inadequacy and unavailability of cooling infrastructures compel people to engage in constant negotiations and compromises. These negotiations are necessitated by periodic power outages and the breakdown of cooling devices, the absence of shading infrastructure, and architectural designs that rarely take thermal comfort into consideration. In the design of Karachi’s largest public university, notions of identity and specific visions of development have long overshadowed conversations about thermal comfort and heat exposure.

Twentieth-century processes of decolonization in newly independent states were rooted in self-representation.1 The built environment became ground zero for these representations, and public buildings, particularly universities, were emblematic of progress, identity, and modernity. After its independence in 1947, bureaucrats and planners in Pakistan sought to establish a distinct identity for the capital city of Karachi, replacing the architecture of its colonial past with one that symbolized modernity. To achieve this, international architects were invited to deploy their skills, adapting elements of modern architecture for tropical climates according to the principles of tropical modernism.2 In the early 1950s, Michel Ecochard, a French architect and contemporary of Le Corbusier, was assigned the task of designing Karachi University, the first public university located at what was then considered the city’s periphery. Applying the principles of modern architecture to Karachi’s climate, Ecochard suggested that:

In a country where the wind plays such an important part in the comfort of the inhabitants, the right orientation of [buildings] will be the principal factor in the arrangement of the urban district.3

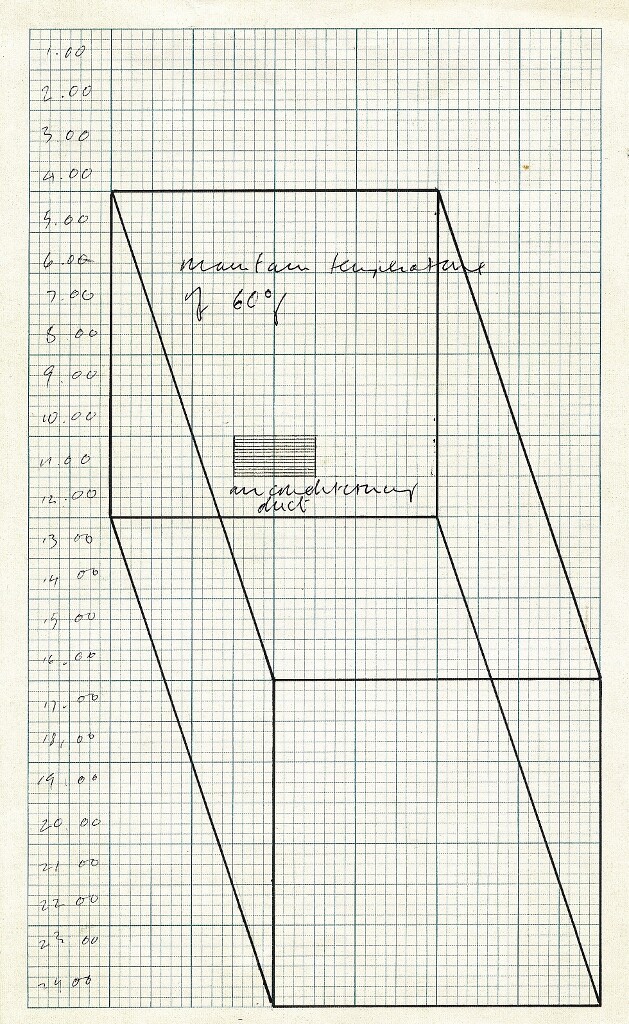

Ecochard’s theories of climatic responsiveness in Karachi were informed by and related to the work he had undertaken in other newly formed nation states in the mid-twentieth century, such as Guinea, Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Cameroon. Confronted with the challenge of designing at a site where electricity and other infrastructural provisions were yet to be delivered, Ecochard conceived the architecture of the Karachi University campus under the assumption that it must survive its first few years of existence without any mechanical cooling and electricity.4 Ecochard’s effective design, which focused on wind direction, shade provision, and a cognizance of the specific topographical features of the site, can be called “before comfort.”5

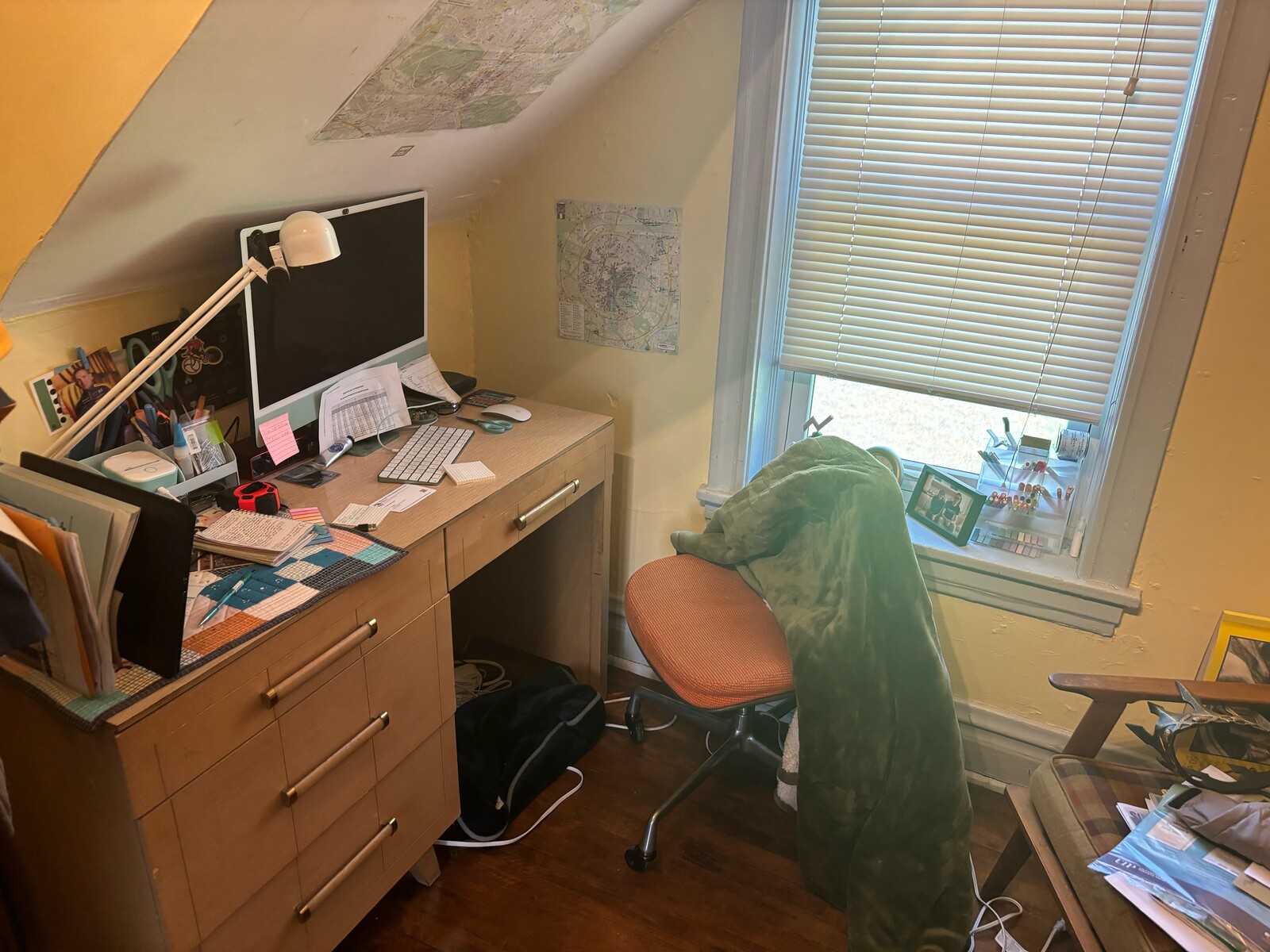

Elements such as the brise-soleil, the east-west orientation of windows, facades designed to catch the southwest breeze, shaded promenades, balconies, and an abundant use of screens remain visible features in Ecochard’s designs. By intertwining the existing natural landscape with architectural elements, his design produced spaces on campus that are thermally comfortable. Walking around these buildings today, the breeze passing though these corridors is impossible to miss. They are favorite loitering spaces for students seeking respite throughout the day, particularly during peak sun hours.

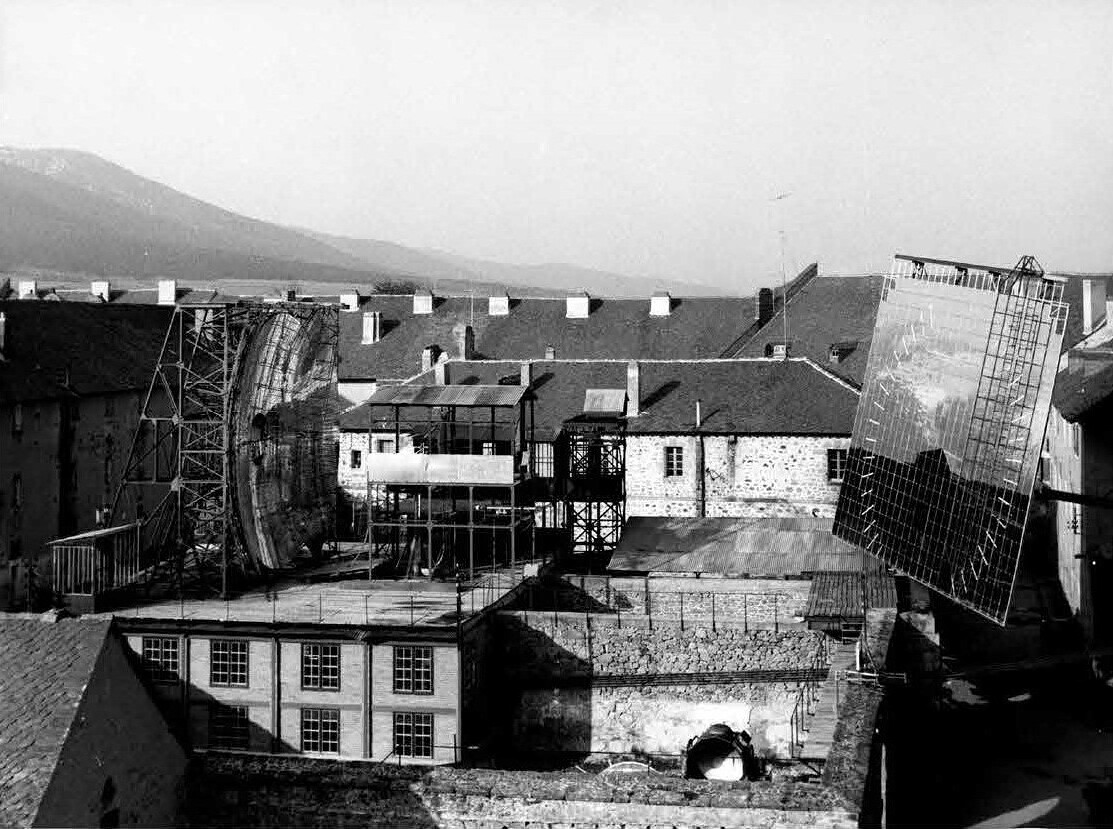

Ecochard placed great emphasis on the idea of habitat evolutif (“evolutionary habitat”), or the ability of a design to be altered over time according to the changing aspirations of the local citizens.6 However, as mechanical systems of comfort took over the way buildings were conceived, designed, and inhabited in Karachi in the late 1990s, new interventions were unfolding on the university campus. His buildings were subject to a wide array of interventions, most of which involved retrofitting them for a transition towards a “fossil fueled comfort.”7 These interventions deviated from Ecochard’s conception of evolutionary habitat and obscured his original design intent. Consequently, previously open concrete screens are now entirely filled in, air conditioners have been added to building facades, new screens seal existing basement openings meant for light and wind, and open terraces have been enclosed to regulate and standardize the thermal experience of the interiors and reduce cooling loss.

It is difficult to ascertain the original designs of most of Ecochard’s buildings since their transition to regulated comfort. Glass windows cover what was originally an open brise-soleil, rendering natural ventilation impossible. New structures are parasitically attached to older ones, albeit with little thought or attention to thermal comfort. One such structure includes a sculpture workshop that shares its wall with one of Ecochard’s original designs; with a black painted tin roof, it inadvertently replicates the experience of a burning oven on a hot afternoon. Furthermore, the uncoordinated and ad-hoc pursuit of comfort through mechanical means has failed to factor in the frequent power breakdowns on campus and the ensuing need for students to occupy outdoor spaces during prolonged outages. It is in these moments that students seek respite in those windy corridors designed by Ecochard. Unfortunately, these have also undergone transformations, and today, the wind in these corridors is blocked by new structures designed to meet the needs of an ever-expanding university.

Undeniably, buildings are meant to evolve. As the needs, aspirations, and desires of inhabitants change, the spaces they occupy must transition as well. However, when such interventions are executed without foresight or in a way that is insensitive to the original design of buildings, they may inadvertently do more harm than good to its occupants. Attempts to retrofit Ecochard’s buildings on the Karachi University campus towards regulated comfort have blatantly disregarded its contextually relevant design principles. His concept of habitat evolutif has its bleakest interpretation in the remaining structures on campus.

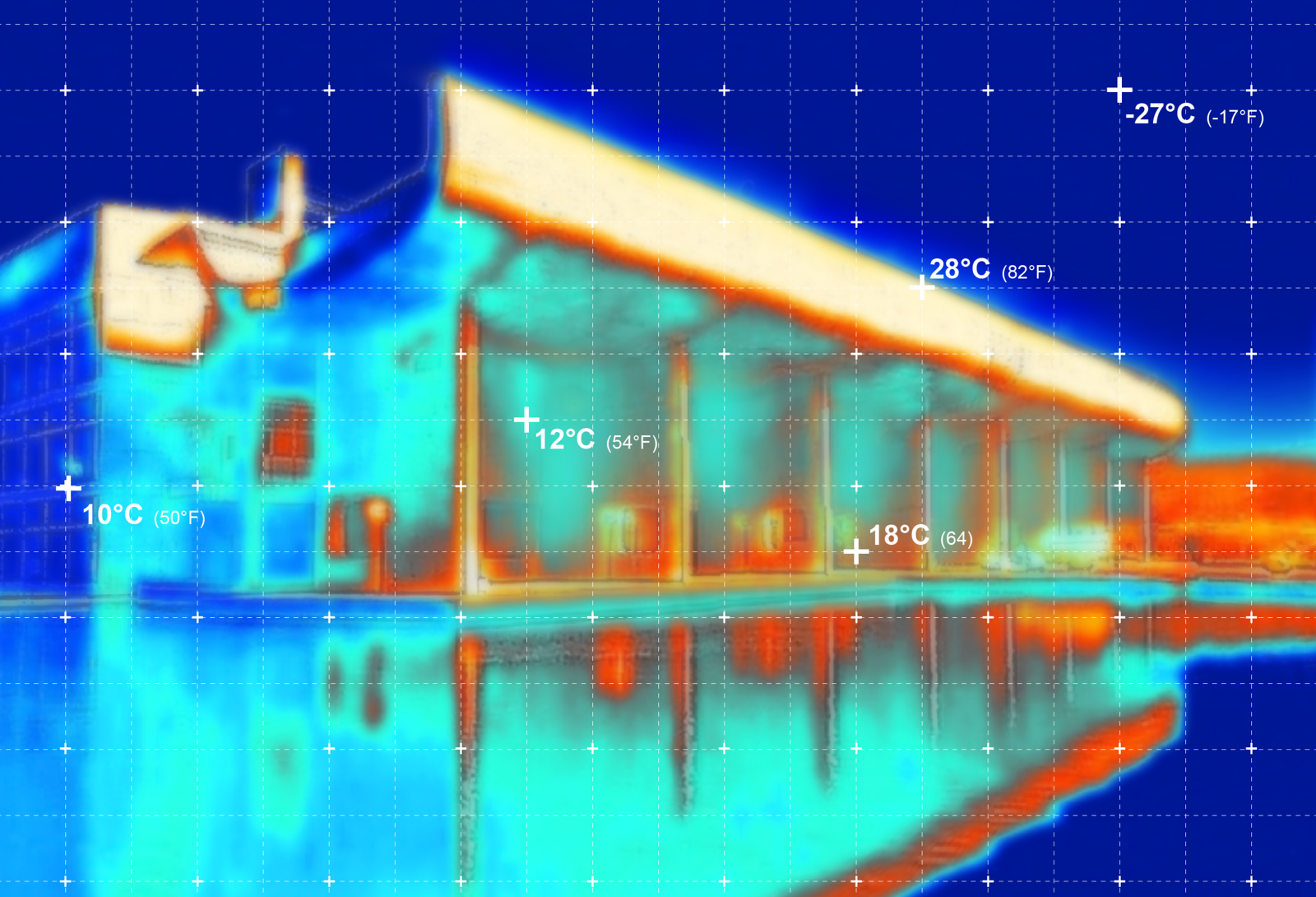

In the context of anthropogenic climate change, Karachi has warmed considerably over the past sixty years. Night-time temperatures have increased by 2.4ºC and day-time temperatures by 1.6ºC.8 Moreover, Karachi University is no longer on the city’s periphery. The university’s surrounding area has urbanized and, both outside and within campus, medium-density mid-rise construction dominates. Karachi’s urban heat island effect is exacerbated by warming temperatures and intensifying heat waves. This has led to a rising demand for shaded spaces and better ventilation in buildings around the campus. But such spaces are hard to find. Instead, bodies moving around the campus are increasingly exposed to the harshness of high solar exposure.

The visions of bureaucrats and planners have also shifted over the past sixty years. From the ideals of modernity to the desire to align with global conceptions of a “world-class city,” the city’s architecture is evolving to meet these changing aspirations. New structures and buildings on campus use abundant glass, concrete, and asphalt with limited green cover. Outdoor spaces now prioritize manicured grass and lawns over trees, with aesthetic preferences geared towards alien species of palm trees that deprive pedestrians of any shade. These material assemblages create heatscapes in and around buildings, designed with minimal attention to passive ventilation and relying on sealed building enclosures to cool through mechanical means.9 In the “Comfortocene” and its focus on interior consistencies, these buildings have become uninhabitable in the event of a power failure or when devices break down, which ironically happens because of extreme heat.10

Newly constructed buildings on campus prominently feature external air conditioning units that expel hot air into corridors. This is in addition to the “embedded solarities” trapped by building materials due to a lack of shading devices on southern facades.11 Some designs draw on nostalgic references from Islamic architecture, comprising false arches and domes, yet they fail to incorporate any of the non-energy-intensive vernacular cooling properties that were characteristic of this architectural style. Conversely, designs borrowing heavily from classical European styles disregard the effective spatial features of those forms and reduce them to visual references to a style that was considered ill-suited for this climatic context even during colonial times.

Ordinary citizens in Pakistan must cope with the daily impacts of energy poverty and survive within the interstices of infrastructure that is unavailable, inaccessible, unpredictable, or unaffordable.12 Under such infrastructural uncertainties, architectural design and the materiality of these heatscapes is perhaps the only means of achieving some degree of thermal comfort, or at least reducing discomfort. As summer temperatures of 40ºC and higher become the norm for Karachi, architects must reconsider and reconceptualize comfort and livable spaces and how they design for it. The pressing yet overlooked need for transitioning away from fossil-fueled comfort would benefit from re-examining architectural interventions from before mechanical comfort became the normative way of conceiving habitable spaces. Ecochard’s designs from before comfort exemplify the benefits of passive ventilation for sustained comfort, and should become the subject of detailed studies to derive lessons for the future scorching city.

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking after Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), 2.

Tom Avermaete, “Monuments of Country, Climate and Culture: Michel Écochard and the Design of the Postcolonial Tropolis,” docomomo journal 63 (2020): 32-39. See also Hannah Le Roux, “The Networks of Tropical Architecture,” Journal of Architecture 8, no. 3 (2003): 337-354.

Michel Ecochard, The University of Karachi, manuscript, IFA, fonds Écochard, Centre d’archives d’architecture du XX siècle, (1965).

Shabbir Kazmi and Mariam Karrar, “Architecture: Ecochard in Karachi,” Dawn, November 26, 2017. See ➝.

Michel Écochard, Gérard Thurnauer, and Pierre Riboulet, Report on the Proposed Plan of the New University of Karachi. Karachi (1954).

Tom Avermaete and Michel Écochard. “Crossing Cultures of Urbanism: The Transnational Planning Ventures of Michel Ecochard,” Crossing Boundaries, Transcultural Practices in Architecture and Urbanism, OASE 95 (2010): 22-33.

Daniel A. Barber, “After Comfort,” Log 47 (2019): 45-50.

Nausheen H. Anwar, Hassaan F. Khan, Adam Abdullah, Soha Macktoom, and Aqdas Fatima, “Heat Governance in Urban South Asia: The Case of Karachi,” (2022). See ➝.

Kara Murphy Schlichting, “Hot Town: Sensing Heat in Summertime Manhattan,” Environmental History 27, no. 2 (2022): 354-368.

Barber, “After Comfort.”

Nicole Starosielski, “Beyond the Sun: Embedded Solarities and Agricultural Practice,” South Atlantic Quarterly 120, no. 1 (2021): 13-24.

Adam Abdullah, Soha Macktoom, and Nausheen H. Anwar, “Thermal Comfort and Cooling Technologies Amongst Low-Income Households and Informal Outdoor Workers in Urban South Asia,” (paper presented at Cooling Asia: Technology, Environment and Society in Hot Climates, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, November 2022).

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.