A Forest Was Filling the Room

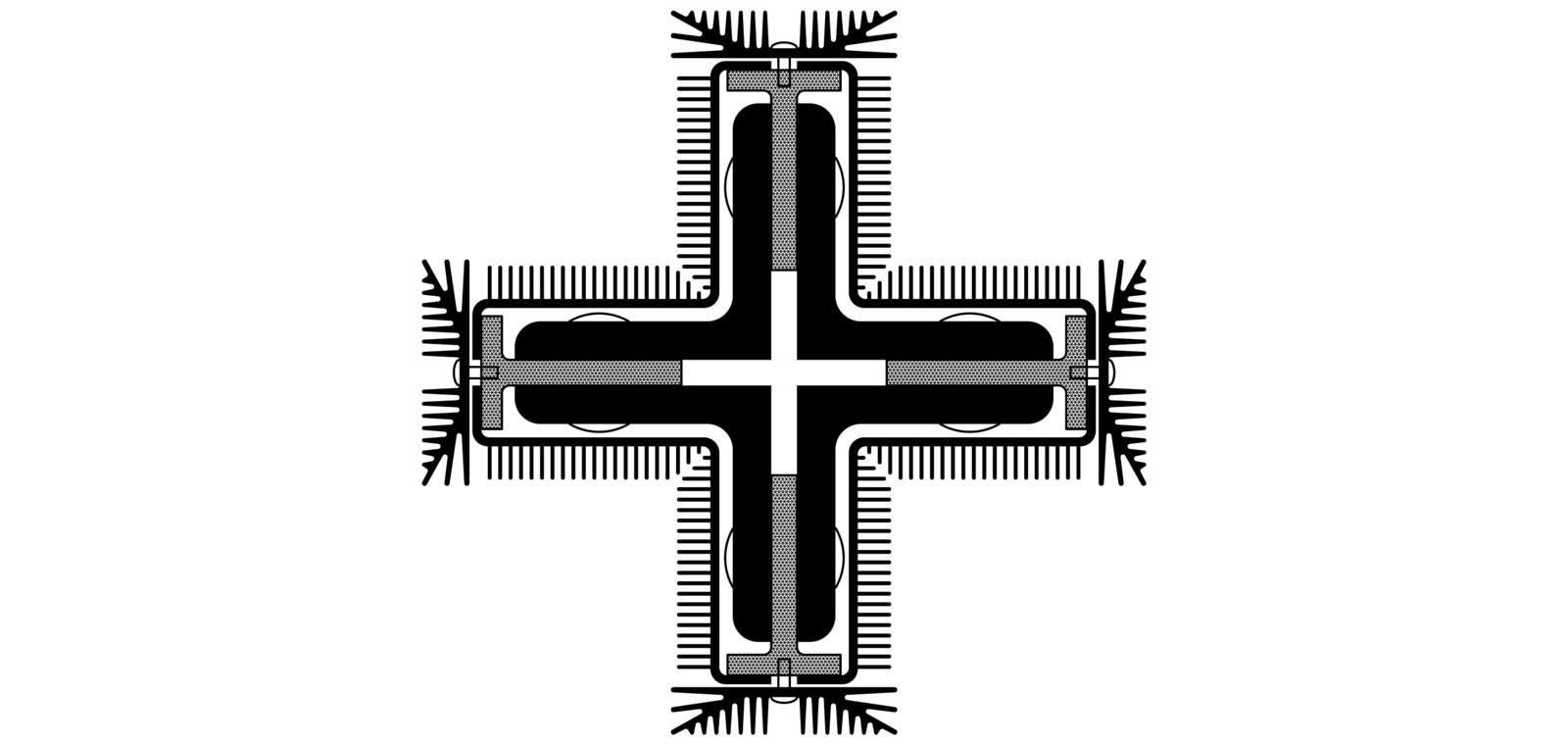

Architects and designers tend to think of themselves as agents of change and innovation, yet what they do is overwhelmingly reactionary. Indeed, design mobilizes and transforms disparate objects and materials towards one another, unlocking their ability to communicate and interact. For example, the design of a window will guide the manufacture and assembly of glazing units and aluminum frames, and allow them to perform, together, in ways that the original materials or components could not. However, if the outputs of design spark new affordances and potentials, they do so by relating to—and abiding by—pre-existing networks, standards, and infrastructures.

Potentials (the ability to do, or the ability to change) do not exist in a vacuum. They are not essential or intrinsic to designed objects (a pencil can write), but woven and wrought across physical and extra-physical networks (the ability to write is an emergent property of the encounter between a pencil, a sheet of paper, and a human hand; a direct consequence of the mining and processing of graphite ore; the result of writing lessons; etc.). To design a pencil, that is, one must presuppose the sheet of paper as a writing substrate, or at least take for granted what writing is.

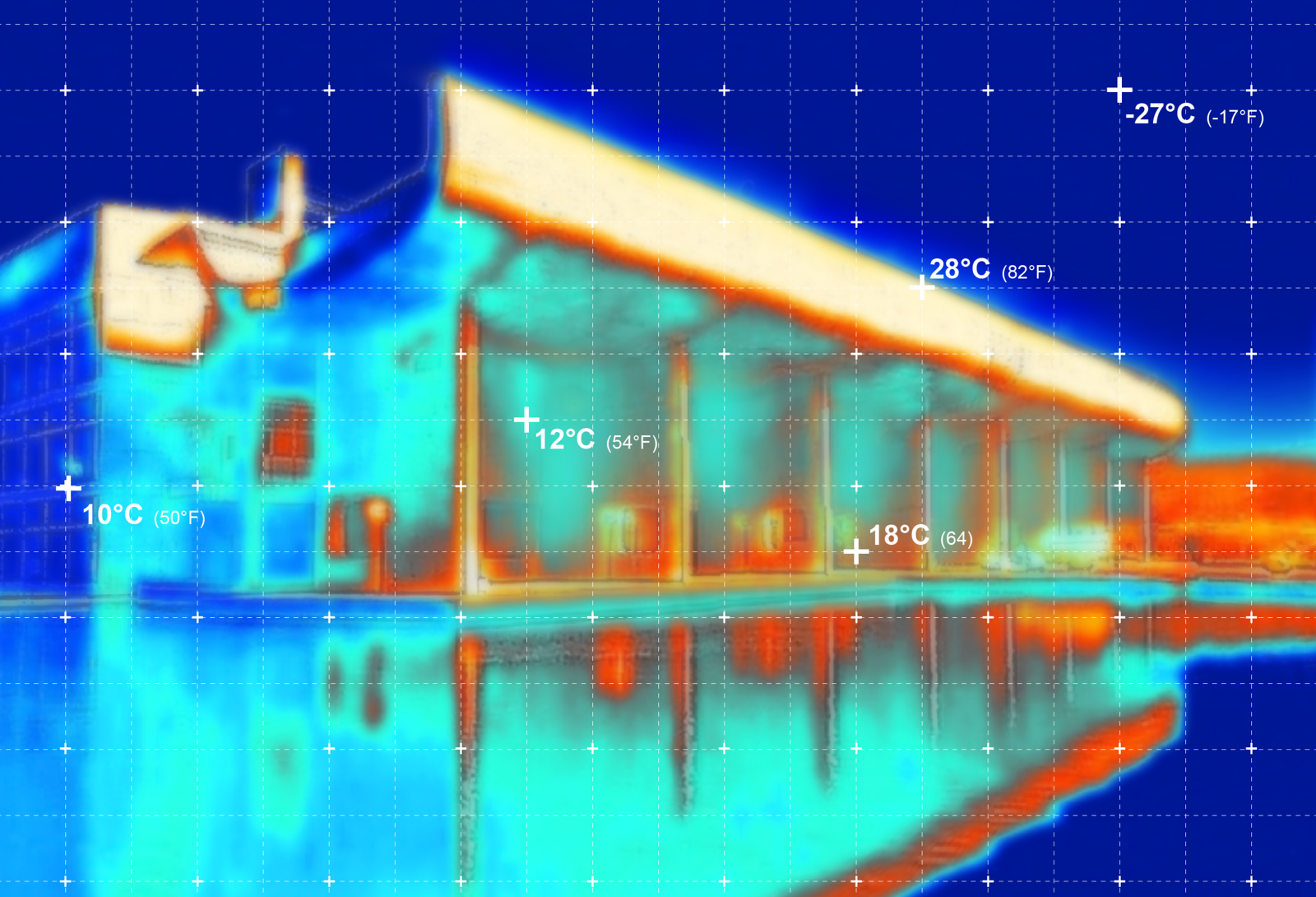

The same goes with buildings. A window affords views, natural ventilation, and insulation by condoning the environmental violence associated with the extraction of sand and bauxite ore.1 The clarity and transparency of low-iron glass is a direct consequence of polluting regimes that include “a radical increase in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide and nitrogen oxides.”2 A door is openable by endorsing a particular kind of body (the one capable of opening it) as its appropriate or universal user.3 And if a floor-to-ceiling curtain wall can be hermetically sealed and feature no openings, it is only by presuming that fresh air and comfort will continue to be provided by energy-intensive heating and cooling systems.4 Design decisions are never just decisions about a design.

Discourses about the Anthropocene have prompted a growing awareness of the spatial and temporal disjunction between the narrow focus or articulation of design intents and the actual effects of design decisions on human and nonhuman systems. It is therefore not surprising to note that buildings in over-consuming countries are often vectors of ecocide, uneven exchange, and environmental injustice.5 While their formal, conceptual, or functional content might offer some measure of innovation, agency, or even delight, they also perpetuate, naturalize, and unmark the status quo and its violence. In this sense, it might be time to admit that a building’s habitability or value does not solely rely on the building-object (a “machine for living in” or the associated projects), but on the widespread spatiotemporal ecologies upon which it depends, from the continued operation of HVAC systems to the baking of limestone, the provision of electricity and potable water, the felling of trees, the inheritance of stolen land, the polluting remainders of aluminum production, the weekly dusting of furniture, and the opening and closing of windows, just to mention a few.

I call these extended networks “ecologies of inception.” While the word “ecology” (from the Greek oikos, meaning family or house) identifies a fundamental relational unit (one that could replace objects and their shapes as the focus of design), the term “inception” foregrounds, on the one hand, the stimulation of novel interactions and affordances (from the Latin incipere, to begin, and capere, to be receptive, to grasp), and on the other, the violence implicit in annexation, appropriation, and incorporation (from in-capere, to capture, to enclose).6 The two etymological roots overlap: new powers (from the Latin potere, to be able) are often powers acquired—or taken—from somewhere or someone else.

A passage from Marguerite Yourcenar’s novel The Abyss vividly captures these transfers and translations, and the shift from objects to the ecologies they compose, both in synchronous arrangements (between stools, tables, doors, and human bodies) and in diachronic ones (the associated displacements of resources and embodiments of energy, labor, and violence). She writes: “Objects no longer played their part merely as useful accessories … they were beginning to reveal their substance.”7

A forest was filling the room: the stool, its height measured by the distance that separates a seated man’s rump from the ground, this table which serves for eating or writing, the door connecting one cube of air, surrounded by partitions, with another, neighboring cube of air, all were losing those reasons for existing which an artisan had given them, to be again only trunks or branches stripped of their bark… [Here] and there the carpenter’s plane had left lumps where the sap had bled. These corpses of trees were laden with ghostly leaves and invisible birds, and still creaked from tempests long since gone by. This blanket and those old clothes hanging on a nail smelled of animal fat, of milk, of blood. These shoes gaping open beside the bed had once moved in rhythm with the breathing of an ox at rest on the grass; and a pig, bled to death, was still squealing in that lard with which the cobbler had greased them… Everything was actually something else: the shirt that the Bernardine sisters laundered for him was, in reality, a field of flax, far more blue than the sky; but it was, at the same time, a mass of fibers put to soften in the bed of a canal.8

The Postbox Turns into a Nest

Zygmunt Bauman describes modernity as a “condition of compulsive, and addictive, designing” because it shares with design the common recipe for the construction of powers: the drawing of boundaries that separate that which “works” and has value from that which, and those who, are unproductive and can thus be disposed of and forgotten.9 When viewed from the narrow perspective of a single project (for example, the design of a bicycle, or the cultivation of food in the former British colonies), an ecology of inception is the apparatus through which such boundaries are drawn. It marks a zone of potential cooperation, action, and interaction (e.g., the ability of the various components in a bicycle to co-function, or the effectiveness of Western forms of cultivation), while also tracing the borders of an epistemic territory that rejects and obliterates what lies beyond, or what fails to comply with its scripts (e.g., the disposal and replacement of a rusted bike chain, or the eradication of non-European models of land ownership and agriculture).10

In this extended sense, the repurposing of buildings that depend on (and are the product of) energy-intensive, life-supporting systems—what Elisa Iturbe calls “carbon form”— addresses more than questions of performance, sustainability, creativity, and architectural merit.11 It lifts the curtain on modernity’s “semblance of totality,” claiming other ways of being possible—other forms of imagining, knowing, and living.12

To repurpose is to change the functional orientation of an object, usually maintaining a degree of integrity in the original structure or form. But it is also to forgo and rewrite its presumed ontology (what it is), and to leverage and divert the ecologies that surround and comprise it. To the common names of objects correspond presumably fixed identities (e.g., a mannequin is a dummy for displaying garments; an escalator is a staircase moving people across floors) that are constructed by narrowing the object’s horizon of use—by identifying the intended users and uses (its telos or function) as the only possible or appropriate ones. Yet, if potentials are not intrinsic to objects but a function of situated encounters, then what an object is or does remains contested and contestable, and continues to change over time.

Sara Ahmed explains that when birds nest in a postbox, the postbox turns into a nest.13 “Something is what it provides or enables,” she writes, “which is how what something ‘is’ can fluctuate without changing anything at the level of physical form.”14 The same is true of buildings, or at least is true enough to challenge their demolition. Here, the gap between form and function—between what a building is and what it is for—can turn into a reservoir of emancipatory potentials, one that could be steered towards Ahmed’s “queer use” (the use of things “in ways other than for which they were intended to be used or by those other than for whom they were intended”),15 Giorgio Agamben’s “inoperativity” (“a subversion of the established relations between means and ends”),16 or Aníbal Quijano’s “delinking” (“a de-colonial epistemic shift leading to other-universality, that is, to pluri-versality as a universal project”).17 To dismiss a functionalist view of powers (of what something or someone can do) is not only to imagine or defend the emergence of other ecologies or uses, but to postpone the very subordination of value to productivity, action, or goals.

Borrowed from evolutionary morphology, the term “exaptation” is useful for thinking about the suspension or delaying of functionality, and about how design outputs (what they are; what they can do; what value they retain) exceed the singular projects, ecologies, or generations that might have wrought them into existence. Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vbra coined the term to describe the nonlinear history of complex biological features, noting that these are not only built by natural selection for their current function (ad + aptus, towards a fit), but also co-opted by reason of their form (ex + aptus). In other words, complex biological features are often constructed over subsequent waves of primary adaptation, exaptation, and secondary adaptation.18 Yet, if utility can be, as Gould and Vbra contend, a “future condition,” then the present usefulness of a form may be as relevant as its continued availability and co-optability.19 Exaptive design, in this sense, suspends the purifying obsessions and hubris of modernity, committing both to staying with the imperfect and polluted reality of that which already exists, and to the radical reset-ability of the parameters according to which it is deemed suitable to perform particular roles or tasks.20

Carpet Beaters, Tricycles, and Hula Hoopers

In 2022, the owners of the Ocean Terminal shopping center in Leith, Edinburgh invited The Living Memory Association (THELMA)—a charity that promotes the recording and sharing of life experiences and oral histories, and that already occupied spaces in the center—to turn a section of the building that had remained vacant after the closure of a Debenhams department store into a community and heritage center. What resulted is the so-called Wee Hub. The arrangement relieved the property owners of a large tax burden, while making over 90,000 square feet of space available to local communities for free, at least until the approval of the center’s future demolition and redevelopment. The resulting diversions and co-options are exemplary of exaptive design across a range of ecologies and scales. If stories about the repurposing of spaces tend to hinge on single turns of use (from X to Y) demonstrated by photographic evidence (before and after), the changes made in the Wee Hub are simultaneously more radical and subtle—more distributed, layered, and unstable.

While their “Museum of Memory” is housed in an adjacent unit, THELMA, alongside other local heritage and reminiscence groups, also occupies an area (the Wee Heritage Hub) on the upper floor of the old Debenhams. Here, the department store’s partitions and shelving units, previously used to display and advertise merchandise—to promote consumption and the modern obsession with the new—are turned into time capsules, preserving and celebrating the past. Old objects—magazines, books, toys, hats, photographs, washboards, food containers, tape recorders, board games, cameras, and so on—line surfaces and are stored inside cashier counters as curiosities landed from a different planet. Opening a drawer, one finds a carpet beater and a message: “carpet beater—before vacuum cleaners, you would beat the dust off rugs and carpets with this!” What is so powerful about these displays, which are surrounded by couches, armchairs, and coffee tables in what appears to be large, common living rooms, is not only nostalgia, or that they foreground and make visible relatively recent changes in how people live—describing a familiar shift from skilled labor and care towards carbon-powered comfort and convenience. Most objects, separated from their primary ecologies of use, remain unlabeled and unnamable, and don’t make sense unless re-coupled with those who made, experienced, used, named, and remember them. The object in the drawer, that is, can only be a carpet beater in connection with the rug and with the person doing the beating, and only for those capable of recognizing it as part of a carpet-cleaning ecology. In this sense, the objects are triggers and openings for cross-generational communication: for asking questions and for cherishing those who can answer them.

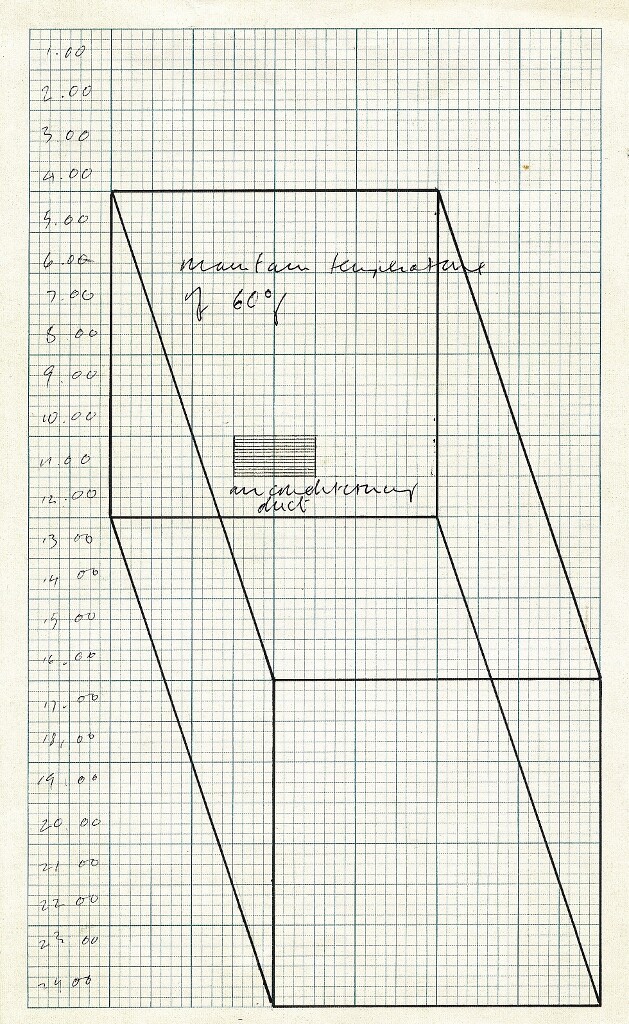

The large floor plate and lack of natural ventilation or lighting in the vacated department store present a challenge, and so does the fact that, depending on who you ask, the HVAC system is either broken or not being turned on. As upgrading a soon-to-be-demolished building would be foolish, the Wee Hub remains stuck in an intermediate state, as a limit case and prototype for repurposing stranded assets through (almost) occupation alone. One community response has been, of course, to wear many layers of clothing, to drink warm tea, and to not occupy the building during the coldest spells of winter. Another, however, has been to reimagine the thermal practices afforded within it.

Fencing class at the Wee Hub, 2023. Photo: the Wee Hub. Courtesy of THELMA.

Dance class at the Wee Hub, 2023. Photo: the Wee Hub. Courtesy of THELMA.

The Wee Hub’s escalator garden. Photo: the Wee Hub. Courtesy of THELMA.

Fencing class at the Wee Hub, 2023. Photo: the Wee Hub. Courtesy of THELMA.

The circulation through a conditioned department store is designed to funnel consumers along paths and browsing aisles, into changing rooms and checkout lines. Breaking these prescribed shopping choreographies allows vast areas to be cleared and made available for nonstandard movement and the warming and sweating of bodies: children on scooters, balance bikes, and tricycles; ping-pong players; dancers and dance teachers; fencers and fencing instructors; hula hoopers; soccer players; acrobats; jugglers; unicyclists; etc. The mirrors that reflected private dressing and undressing scenes now stand next to one another in arrays along rehearsal studios, providing visual feedback to free dance classes and circus community jams. The escalator, which sits under the only source of natural light, a skylight, is now a linear community garden—moored into place, filled with potted plants, and cared for by a dedicated gardening club.

Another response to the building’s spatial and thermal conditions has been to retain it as storage, or rather, as a holding area for the reclamation and reactivation of discarded objects. A local charity displays available items of furniture and organizes weekly up-cycling workshops. Another runs a digital arts program and maker space, also storing and repairing musical instruments to be donated to libraries and schools across Scotland. On the same floor, large quantities of disused pianos are retuned and offered up for adoption. What is significant here is not simply a shift from the sale of primary goods to the reclamation, repair, and reconditioning of secondary ones. By keeping materials and components in a state of suspension—preserved and co-optable—these initiatives bridge the temporal gaps between their availability on the market and their reusability or exaptability; between their embodied (real) value and their value as set by the ecologies to which, one day, they may return or be consigned. The size of the building and the scale of operations possible within it also suggest a much-needed move from the individual domain of the bricoleur’s stock toward urban-scaled infrastructures for the collective keeping and sharing of resources.

Some of the most striking examples of repurposing in the Wee Hub are the interventions curated by Pianodrome, a social enterprise that, aside from diverting unused pianos and making them available to the public, also disassembles untunable ones and reassembles their components into sculptural and architectural constructs.21 A trail of reconfigured pianos punctuates the two floors, guiding visitors around the space. The largest assemblage is an amphitheater-cum-musical-instrument comprising three seating wedges made entirely out of discarded pianos and piano parts. It anchors the reoccupation of the department store, turning it into a venue for concerts and performances, for spending time together (beyond the opening hours of the old Debenhams) and for gathering small crowds (incidentally, one more way to generate heat). There, as in many of the department store’s spaces, visitors are endowed with the rare ability to be loud or to participate in loudness: the exhilarated screaming of children playing around a cashier-counter-turned-pirate-ship; the cheering and clapping of young adults during live music performances; or the singing of a choir composed entirely of elderly people with dementia.

Many worlds overlap and collide here, negotiating precarious boundaries of coexistence and forming new bonds of solidarity, reciprocity, and community—artists, filmmakers, pensioners, cooking classes, knitting and craft clubs, chess tournaments, underprivileged children, teenagers, reading groups, language instructors, volunteers, circus and carnival artists, model makers, refugees, curators, teachers, musicians, and so on. While the Wee Hub’s destiny remains uncertain—and the building will likely be demolished—its remarkable social and cultural vibrancy demonstrates that the value of buildings cannot be decoupled from dispositional horizons of use. More precisely, it exemplifies how value can emerge from (rather than precede) new patterns of use and regimes of habitation.

For an account of the ecological and social degradation associated with the mining of sand, see for example Vince Beiser, “Why the World Is Running out of Sand,” BBC Future, November 18, 2019, ®. For a thorough examination of the history and impacts of the primary and secondary production of aluminum, see Carl A. Zimring, Aluminum Upcycled: Sustainable Design in Historical Perspective (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017).

Andrés Jaque (Office for Political Innovation), “Architecture as Ultra-clear Rendered Society,” in Vanessa Grossman and Ciro Miguel (eds), Everyday Matters: Contemporary Approaches to Architecture (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2022),165.

For insights at the intersection of architecture, design, and disability studies, see for example Aimi Hamraie, Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017); Sara Hendren, What Can a Body Do? How We Meet the Built World (New York: Riverhead Books, 2020); and David Gissen, The Architecture of Disability: Buildings, Cities, and Landscapes beyond Access (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022).

Daniel A. Barber, “After Comfort,” Log, no. 47 (2019).

For an exemplary articulation of this point see Kiel Moe, Unless: The Seagram Building Construction Ecology (New York: Actar Publishers, 2020).

Simone Ferracina, Ecologies of Inception: Design Potentials on a Warming Planet (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2022).

Marguerite Yourcenar, The Abyss (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997), 186.

Yourcenar, The Abyss, 186–7. Italics mine. The passage also reminds me of Jane Hutton’s powerful definition of materials as “fragments of other landscapes.” Jane Hutton, Reciprocal Landscapes: Stories of Material Movements (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2020), 5.

Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity, 2011), 30.

Brenna Bhandar, Colonial Lives of Property: Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 8.

Elisa Iturbe, “Architecture and the Death of Carbon Modernity.” Log, no. 47 (2019), 12.

Rolando Vázquez, “Translation as Erasure: Thoughts on Modernity’s Epistemic Violence,” Journal of Historical Sociology 24, no. 1 (March 2011), 42.

Sara Ahmed, What’s the Use? On the Uses of Use (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 34.

Ahmed, What’s the Use?, 34–35.

Ibid., 44.

Giovanni Marmont and German E. Primera, “Propositions for Inoperative Life,” Journal of Italian Philosophy, no. 3 (2020), 10.

Walter D. Mignolo, “DELINKING: The Rhetoric of Modernity, the Logic of Coloniality and the Grammar of de-Coloniality,” Cultural Studies 21, no. 2–3 (March 2007): 453. Rolando Vázquez writes that “Decoloniality is about delinking: it is about being otherwise. It is about recovering the possibilities of deep relations that overcome gender, heteronormativity, the human-nature divide, anthropocentrism, and individualism and move towards the communal.” Rolando Vázquez, ‘‘What We Know Is Built on Erasure,’’ The Contemporary Journal, no. 1 (January 25, 2019).

Stephen Jay Gould and Elisabeth S. Vrba, “Exaptation: A Missing Term in the Science of Form,” Paleobiology 8, no. 1 (1982): 4–15.

Gould and Vrba, Exaptation, 11–12.

For more information on the notion of exaptive design, see Ferracina, Ecologies of Inception. See also Simone Ferracina, “Exaptive Design: Radical Co-Authorship as Method,” in Rachel Armstrong, Experimental Architecture: Designing the Unknown (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2019), 121–43.

I discuss the story of the Pianodrome before its arrival at Ocean Terminal in Ferracina, Ecologies of Inception, 111–114.

After Comfort: A User’s Guide is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the University of Technology Sydney, the Technical University of Munich, the University of Liverpool, and Transsolar.