In the opening of Theo Cuthand’s fifteen-minute film Extractions (2019), the artist remarks upon the inevitable entanglements between the earth’s plundering and the corporate funding of the arts. Over a close shot of a moving freight train, the prototypical symbol of modernity, he says, “Someone asked me recently if there is any type of funding that I wouldn’t accept to make art and I said resource extraction. But then, while lying in bed, I realized I already had.”

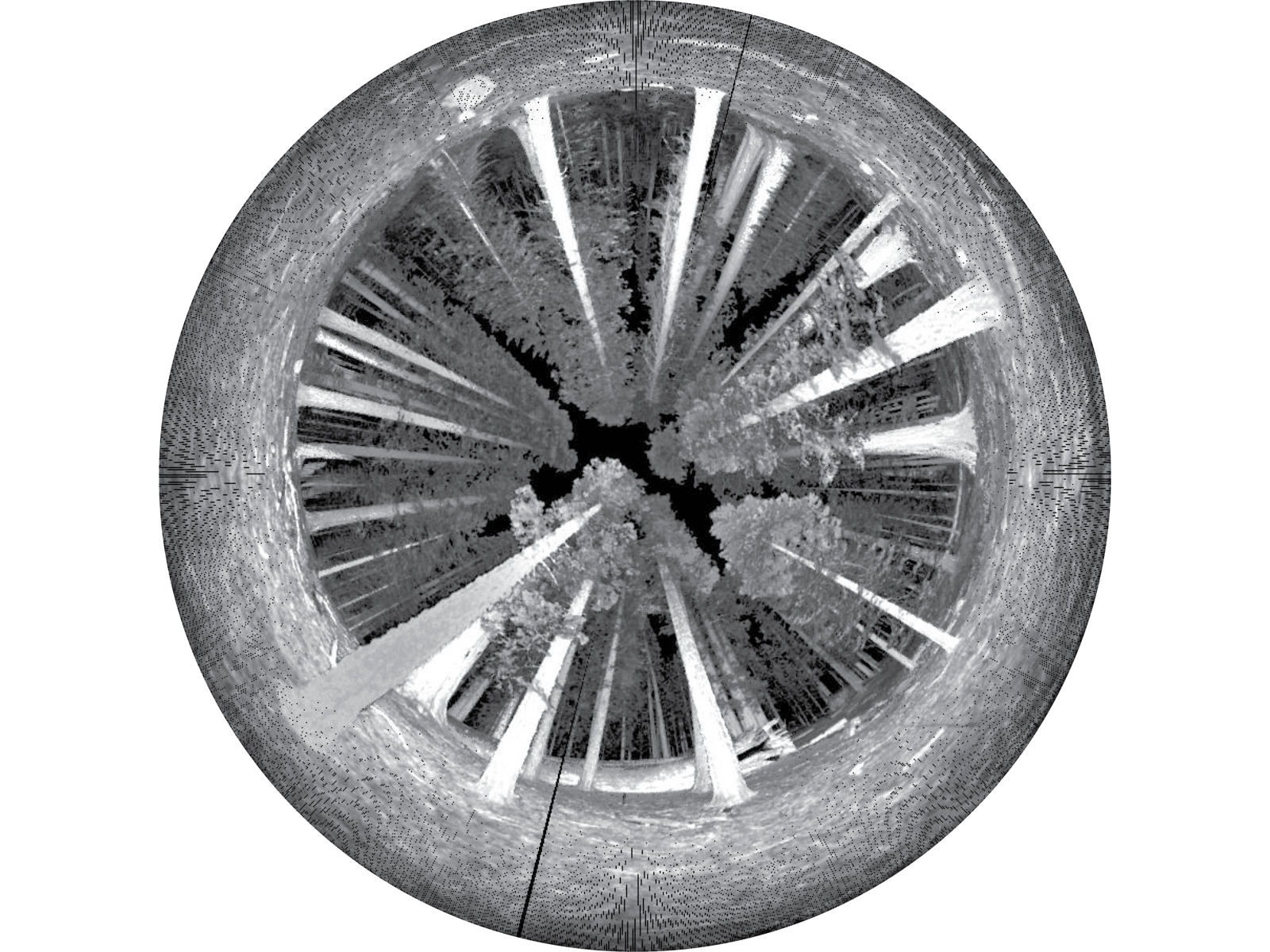

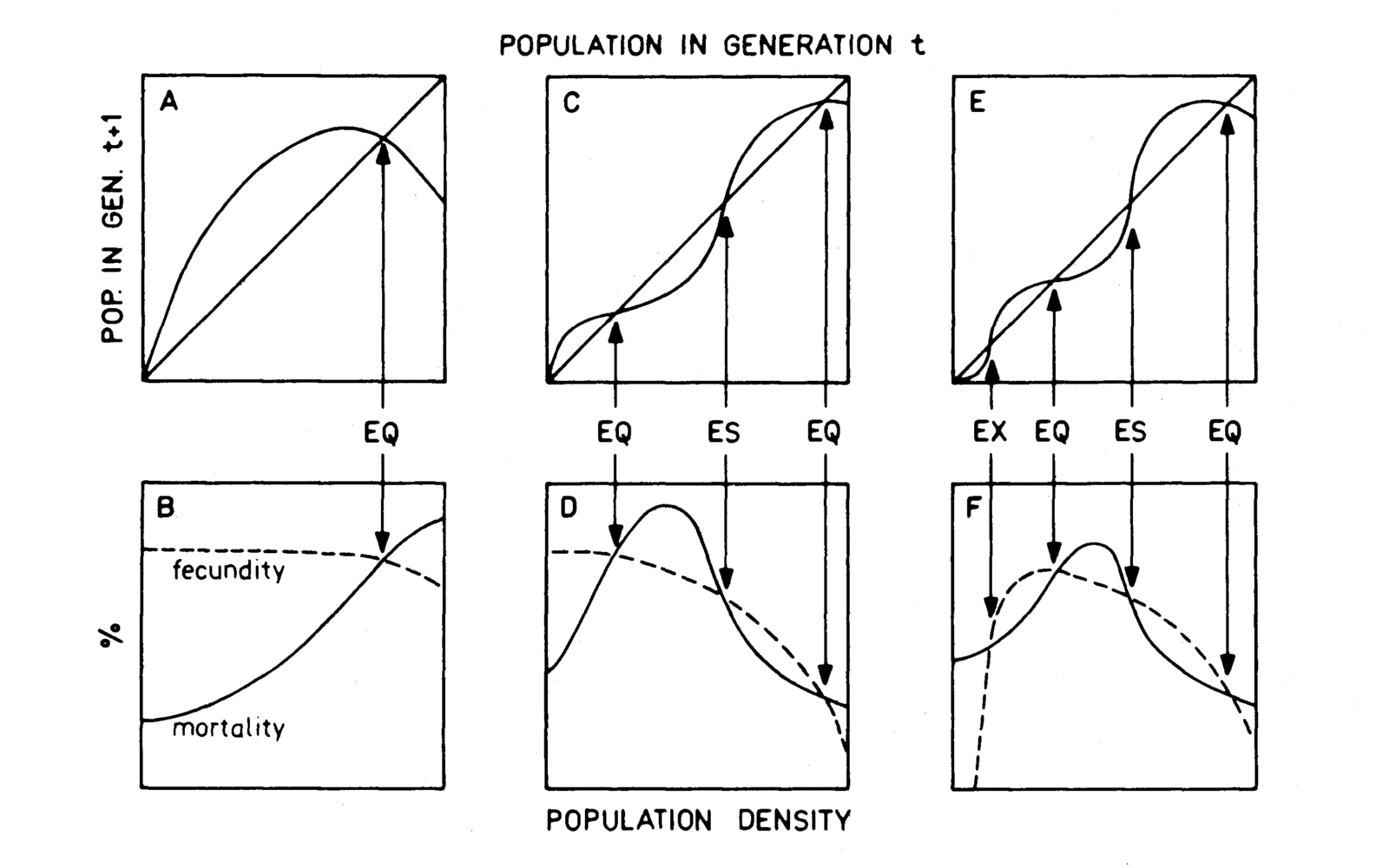

Extractions is organized around archival footage of uranium mining and the blasted landscape in northern Saskatchewan, in the Athabasca Basin of Canada. It is grounded in an Indigi-queer and trans perspective that visualizes how uranium is mined for nuclear power on a global scale. But the film’s visual language does not remain at the level of abstraction, or at the dominant scale of extraction. Instead, through discussion of IVF, egg harvesting, and the instabilities and chemical mutations of the trans-body, the film offers a more intimate and personal take on what it means to live in a neocolonial era of ongoing land exploitation within the liberal Western meta-narrative of progress. It also situates the complexity of Indigenous trans-masculine personhood and its complex relationalities, strategies, and negotiations with the settler colonial world.

At the end of the opening scene, Cuthand explains how he too is implicated in the extractive matrix of power, stating that, as an undergraduate, he received a scholarship from an organization funded by a resource extraction company. Pointing to the pervasiveness of his, and by extension our, creative and intellectual entanglement with extractive industries affords a profound level of reckoning with the extractive beast in our midst. Indeed, the persistent critique of nuclear modernity and settler colonialism that unveils the complex scales of entanglement with land occupation and the carbon and nuclear economy is an important dimension of what Cuthand and other Indigenous filmmakers offer.

The funneling of profits from resource extraction into the museum and cultural industries, as well as within digital economies, is central to uncovering the submerged capitalist relations and their inevitably close connections to more generalized conditions of pollution. We must unearth these architectures to contend with the accumulation, dispossessions, and degradations of extractive capitalism in order to give space to the delicate and resilient worlds of the otherwise by developing alternative models for a livable planet.

Un-Earthing as Method

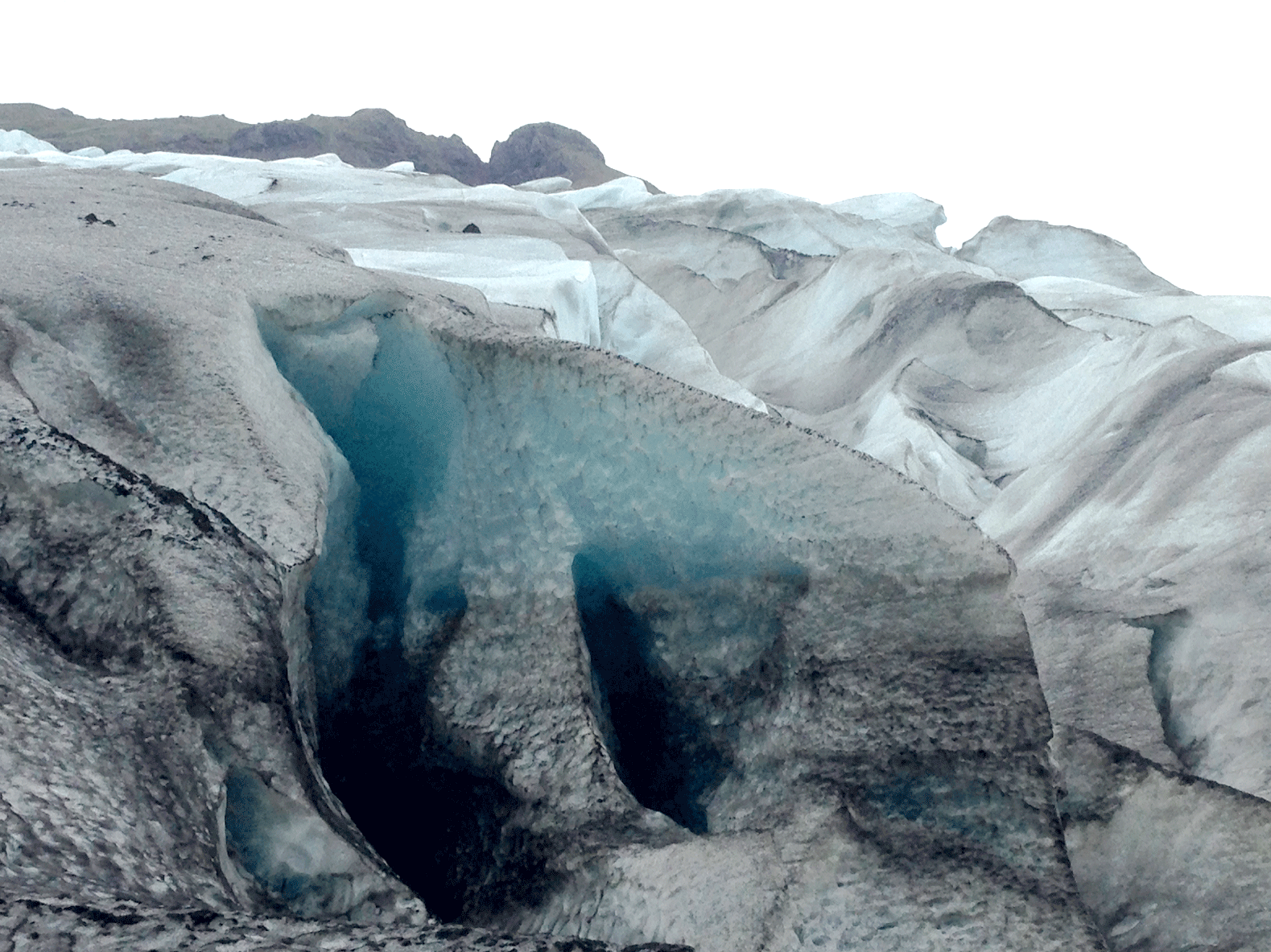

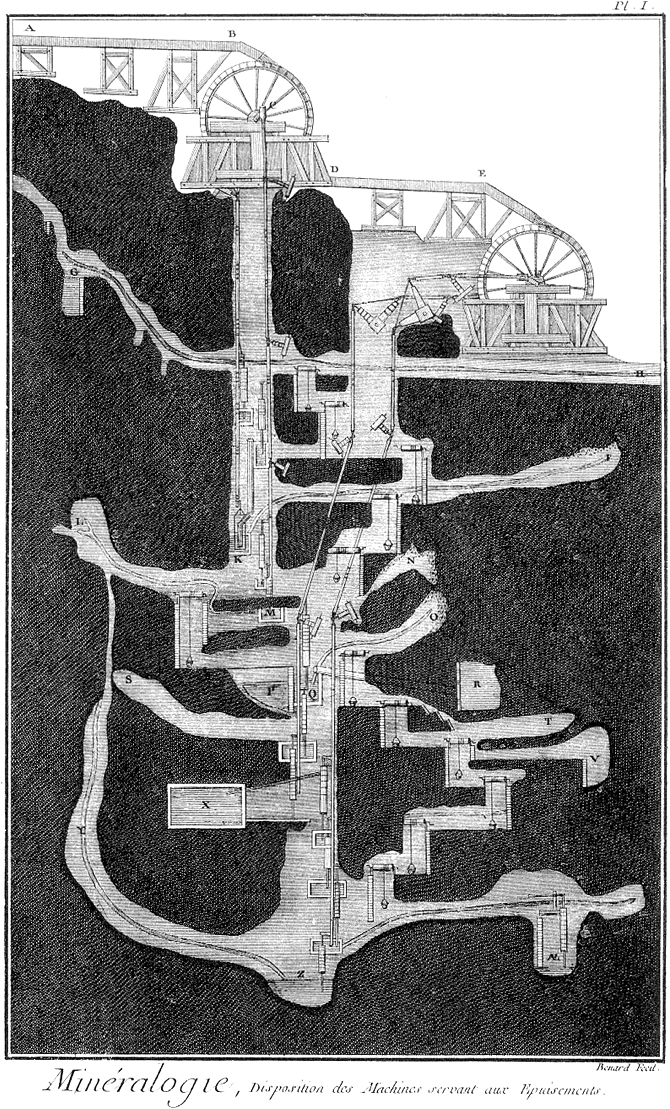

If architecture has been defined as the art and technique of design and building, then unearthing architectures is the decolonial analytical and activist practice that aims to uncover the financialization of culture, art, and the built environment as the long durée of colonial and neocolonial plunder, profit accumulation, and reinvestment. Unearthing architectures is a vital way to piece through the colonial Anthropocene by unveiling an urban model in ruins, one that is dependent upon death and destruction here and elsewhere. Unlike the bulldozer or the military tank (guanaco), this decolonial critical method reaches into the underlands to see how extractive cultural industries are saturated with unjust wealth and cultural capital accumulation by a billionaire class. Such a practice demands that extractive corporate entities be accountable for their art-washing monoculture. It also offers a way to dig up and lay bare the infrastructures that have contributed to a toxic world gravely in need of rebalance, redress, repair, and thinking with and beyond extractive capitalism.

I began this counter form of excavation and documentation in my books Where Memory Dwells, The Extractive Zone, and Beyond the Pink Tide.1 Later, I refined this method by watching and learning from Latin American trans*feminists in the struggle against the heteropatriarchal state, as well as by witnessing the successful campaign by Decolonize This Place (that learned from the Palestinian resistance and Standing Rock Sioux activisms). The latter campaign eventually led to the conditions that forced billionaire Warren Kanders to step down from the Whitney Museum’s Board of Trustees. One focus of the Whitney campaign was to make visible how the weapons companies owned by Kanders, Safariland, and Defense Technology, produced cannisters and smoke grenades used against migrants at the southern US border. Though Kanders had promised to divest from such industries, his ongoing investments in the military-industrial complex continued to accrue gigantic profits for a US and global economy based on war manufacturing, or what the late Kanaka Maoli Native feminist scholar and activist Haunani-Kay Trask calls “mili-capitalism.”2

The name Whitney No More is a reference to Idle No More, the grassroots movement among the Indigenous peoples in Canada, and the Whitney campaign itself generatively exposed the relations between this legendary cultural institution, its position upon Lenapehoking territory, and the violence unleashed against dispossessed migrants crossing the southern border. Within the current right-wing infused political climate that continues to criminalize immigrants as part of the project of reimagining a crumbling nation, it’s important to remember that the forced migrations arriving at this southern border are not homogenous groups. Migrants include Mestizx and Indigenous peoples of all genders and nations, including from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Panama, from Mixtec, Nahuatal, and Mayan-Quiche territories, and from dozens of other Indigenous occupied nations. Many of these migrants have either experienced US Empire directly, or their personhoods, livelihoods, and geographies have been haunted by the afterlives of American intervention.

Given the range of toxic conditions that military, racial, and extractive capitalism have produced, including failing infrastructures, the planetary climate crisis, biodiversity and cultural theft, and the chemical effects of carbon offsets, the museum strike has become an important node of emergent political activity. It is a place from which to unbuild, reimagine, denounce, and redirect resources. In Turtle Island, as throughout Abya Ayala (Indigenous nomenclature for the Americas), the museum has become an increasingly important memory–symbol, a way to make abstract capitalist relations visible.3 As Kirsty Robinson discussed in the wake of Idle No More, growing protest cultures challenge historical colonial relations and their new entanglements by striking museums, and thereby exposing the underbelly of broader economic, political, and cultural neoliberal economies.4

Cultural institutions such as museums and art and film collections, as well as media conglomerates, are primary sites of capitalism’s primitive accumulation, and must be unbuilt or rethought in ways that address these legacies. As artists, thinkers, knowledge makers, activists, educators, and cultural producers, de-cathecting with the dominant model of colonial museum and art industries allows for generative sources of creativity that do not continuously contribute to extractive capitalism.

Un-Earthing the Substrates

Petroleum monopolies and their wealth transfers are not a sideline to the story of modernity, but, like mining, are some of its main protagonists. The oil barons of the nineteenth century were known for their ruthless capitalist practices, and some of them later moved their investments into gold and mineral extraction. The American oil industry, including Standard Oil, Chevron, and Exxon, was built upon black gold—subsurface fossil energy that continues to power economic dependency for many Latin American, Arab, Asian, and Global South nations.5 The Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano renders these capitalist relations visible in his classic discussion of the “resource burden.”

No other magnet attracts foreign capital as much as black gold… Petroleum is the wealth most monopolized in the entire capitalist system. There are no companies that enjoy the political power that the great petroleum corporations exercise on a universal scale….

Standard Oil and Shell lift up and dethrone kings and presidents; they finance palace conspiracies and coups d’état; and they dispose of innumerable generals and ministers; and in all regions and languages, they decide the course of war and peace… The natural wealth of Venezuela and other Latin American countries with petroleum in the subsoil, objects of assaults and organized plundering, has been converted into the principal instrument of their political servitude and social degradation. This is a long history of exploits and of curses, infamies, and defiance.6

Within the subsoil of museum and art collections is a long history of exploits and plundering, where oil, hydroelectric damming, investments in carceral industries, and militarization link the owning class to the condemnation of resource-rich regions of the world. This is what Galeano refers to when he describes the plundering and conversion of the earth’s subsoils into “the principal instrument of their political servitude and social degradation.” Within the underlands of world-class museums lies the curse of resource wars, the subsurface deposits that have historically given rise to militarism as a form of external and state control over finite natural resources.7

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, US military forays in Latin America, the Caribbean, and other parts of the Global South deadened living ecologies in order to acquire primary materials, wreaking havoc along the way for national political autonomy, Indigenous sovereignty, and inter-American political solidarity. The war architecture and the trail of death that followed in its wake were then pronounced to be the “bright future” of the US petrol-expansionist imaginary. For instance, Greg Grandin shows how Henry Ford’s modern colonial adventures were rationalized through his rubber dreams that began in the Amazonian Basin and then extended across the hemisphere, interconnecting the oil economy with the rubber boom, and then with the Americanization of the world’s largest biodiverse region.8 Another instance of extractive interventionism was the Chaco War from 1932–35, in which Standard Oil’s competition with Shell Oil produced a conflict between nations that led to a socially and environmentally catastrophic war between Bolivia and Paraguay.

One cannot overstate how the world’s largest and most powerful art collections are also implicated in resource extraction. Both John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Paul Getty funneled their profiteering from petroleum into art collections, creating the foundation of major US cultural institutions. Solomon R. Guggenheim made most of his profits from silver mining and smelting in Colorado. One of MoMA’s original art patrons, John D. Rockefeller Jr., inherited and built on a fortune made from investments in oil wells in Pennsylvania and Ohio in the nineteenth century.

It is important to mention the gendered implications of these imperial histories of extractivism, war, and architecture that later return as liberal philanthropic motives to establish cultural institutions. Liberal philanthropy often passes through the bodies of tycoons’ wives. For instance, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr., was MoMA’s third president and founded MoMA with her husband and other millionaire wives. Thus, the museum is not an innocuous place that records, collects, and displays art, but a fundamental institution of hegemonic economic, political, and cultural influence. The history of art collecting, then, might also be told through the wives of powerful barons who aim to widen their cultural power in urban metropolises. Empires are forcefully taken, built, and then given away through kinder gestures as museum collections.

Rockefeller Jr.’s deep connection, ties, and direct political influence led to the expansion of the hemispheric carceral state in the latter half of the twentieth century. The Cold War criminalized the Latin American political left, intellectuals, and activists as subversives, producing death, suffering, and destruction in its wake.9 By targeting insurgent and militant groups through imprisonment and disappearance, resource empires created new architectures of security, extraction, and containment. As a new and intensifying phase of capitalism was born within dictatorship, neoliberalism required the decimation of those whose political imaginaries ran counter to the extractive machine. There is no innocence in these cultural substrates, just the damage of authoritarian afterlives and the fosas comunas (mass graves). At the end of his life, Rockefeller Jr. had become not only the world’s richest man, but also its greatest philanthropist. Yet in Latin America, Rockefeller has never been a benevolent paternal symbol, but a figurehead for the cruelties of an American empire that dispossesses by racializing, dismembering, and eradicating.

The obdurate connections between American empire, extractivism, and art are not always as well documented or displayed as they were in the 2020–21 Whitney Museum show Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art (1925-1945). Though I’d seen the mural in art catalogues dozens of times, it was incredible to personally experience the mural replica of Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads, the 1933 fresco that had originally been painted in Rockefeller Center, but was chiseled off the wall because Rivera painted Vladimir Lenin’s figure in direct opposition to Rockefeller, who had commissioned the piece. Influenced by New York leftist groups to make stronger visual connections to power hierarchies in his work, Rivera painted figures of the peasant and the worker as part of a communist future. This rare, overt inscription of the time before the Cold War, and the paternal role of Rockefeller as a kind of heteropatriarchal figure of hemispheric capitalism, offers an important artistic document of US economic and military domination.

Extractivism and Art Washing

Extractive art washing is the recurrent capitalist practice that normalizes colonial and modern relations of biodiverse resource theft by investing in art and art collections as a fungible commodity. This not exceptional in the US, as all nation states in our carbon extractive world depend upon an entangled web of oil and art.10 This does not mean that museums do not have continuing social and cultural value. Rather, it’s important to recognize that they collect, exhibit, and program in the long shadow of petroleum empires. Art ownership is a form of control over political and social value through the fungibility of art as a valuable commodity. A primary feature of collected art is that it expresses and erases the violence of the accumulative practices of capitalism and their carbon and imperial origins.

New York art galleries, museums, and their collections have long served as repositories for the wealth of investment bankers and multibillionaire international conglomerates. The Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, for instance, is a privately held collection based in both New York and Venezuela, founded by Patricia Phelps de Cisneros and her husband, Gustavo Cisneros, that archives a growing collection of Latin American contemporary art. The couple additionally established the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Research Institute for the Study of Art from Latin America at MoMA in 2016. According to the New York Times in 2002, Gustavo Cisneros is “a multibillionaire whose international conglomerate of 70 companies relies on unfettered access to high-ranking political and economic officials in nearly 40 countries.”11 As Galeano noted, such unfettered political access is never innocent in the distribution of myriad forms of inequality.

Cisneros made his fortune through diverse assets, with Venezuelan oil in the pre-Chavez period serving as the foundation of his first earnings. When easy access to underground petroleum reserves proved difficult, Cisneros diversified his portfolio and became one of the richest men in South America. In the post-Pinochet period of expanded neoliberalization in the region, state policies aimed at privatization and deregulation only helped grow Cisneros’s multinational economic and political influence throughout the Americas and world. Currently, Grupo Cisneros is a vast empire based in Coral Gables, Florida, and includes a conglomerate of digital media, entertainment, tourist, and real estate investments with an astounding consumer audience of more than 600 million Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking peoples throughout the hemisphere and in Europe. Grupo Cisneros is also one of the largest investors in Univision, which is broadly known as a conservative media organization with massive, global social and political influence on Latin American and European markets.

The Cisneros MoMA collection was founded by Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, a powerful patron of art in her own right. Yet, behind the surface of what has become one of the most important collections of Latin American modern art and the source of meaningful curatorial projects and fellowships are deep connections to extractive industries. Most recently, gold excavation in Cotuí, Dominican Republic, and in Antioquia, Colombia, has become central to the expansion of the Cisneros’s empire.12 Gold mining is an extremely toxic process that poisons the land. These contemporary currents in the world of American art cannot be allowed to hide the structural conditions that produce a billionaire class by destroying human and more-than-human communities.

Plundering petroleum-rich, biodiverse Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous territories is a core tenet of colonial modernity and capital accumulation in both the Global North and Global South.13 Yet in the digital era, oil, water, forests, and even pharmaceuticals and real estate are not the only lucrative commodities, as the rise of communications and digital media empires are the past, present, and future of extractive capitalism. Media and communications platforms provide valuable source materials that can be abstracted in ways that racialized capital thrives upon.14 These new technologies depend upon the same language as resource extraction, such as “mining” big data, “prospecting” and “collecting” biomatter, “tracking” users through surveillance, and normalizing dispossession through the agendas of the political right. Further, the military state is both the originator of and thoroughly engrained in this new media matrix’s domination.

The ability of the Cisneros Group to accumulate more than twenty billion dollars of net worth through media conglomerates, gold mining, and oil extraction at a time of increasing economic divisions in the world is evidence of the tightening grip of new extractive frontiers. Such investments into art and culture, particularly in New York, are part of the return on extracted value, in the form of appreciation, rent, and a rise in capital gains. In a world that circulates collected art to continually build up the billionaire class while impoverishing the majority—and especially racialized peoples and geographies—the artist and scholar can play an active role in locating, exposing, and unearthing the architectures of extraction.

Post-Extractive Futures

When I lived in Los Angeles, there were important struggles happening in East Los Angeles and in Boyle Heights over art-washing and gentrification of Chicanx historic spaces. Over the past decade, the intimate connections between real estate capitalist investment and an extractive art industry that displaces and dispossesses primarily Black, Latinx, and immigrant communities of color have increasingly polarized many cities. In the case of MoMA, as in the case of other museums like the Whitney, the target has been the board of trustees, where entanglements with weapons, illegal art collections, gold, silver, copper, oil, and media remind us once again of the importance of following the money.

Since Strike MoMA, I have thought a lot about the complexity of what it means to confront liberal institutions for their historic power grabs, their complicity and involvement in petroleum and carbon induced climate change, and their explicit connections to the machine of war, empire, and the exploitation of Indigenous territories. Even as it’s always difficult to speak truth to power, Strike MoMA has demonstrated the importance of transversal and coalitional work in creating new spaces for solidarity in an increasingly authoritarian, skewed, and unjust world.

Veronica Gago points to the state as the horizon of collective political potential.15 Gago builds upon the work of anarchist Rosa Luxemburg to consider how feminist, precarious labor, informal economy, Indigenous, queer, and trans-alliances provide new ways to counter the patriarchal and violent conditions of the modern and colonial state. This is a theoretically rich and elegant argument, and I don’t want to reduce the importance of embodied activism and theory-action work to a few lines. Instead, I would like to consider how the racial and heteropatriarchal state, especially in the Global North, and in particularly in the United States, is not the only horizon of political struggle. In epicenters like New York City, the art museum also represents an extractive epicenter, and an important site for multiple demands and dispossessions.

During the first wave of its efforts, Strike MoMA expressed diverse political articulations. It reflected upon the plight of the Palestinian people in the face of an apartheid state; it connected to Global South decolonization movements; it studied the ongoing struggle for Black people’s freedom, immigrant rights, and internationalism, alongside other issues of south/south and critical forms of solidarity. Maybe targeting carbon centers and media empires is what is needed. Maybe striking in every way possible is exactly what we must do to unbuild the colonial planetary and think towards the post-carbon potential of a non-extractive future.

Postscript: Beyond the Colonial Binary

We live in complicated times, between the loss of one empire and the rise of others; we live in times when crises, both intimate and imagined, local and national, become fodder for the capitalist machine. We live in the fracture, a time when our creative joy and faith in the potential of institutions is hijacked and without innocence. Who doesn’t know how bankrupt the institution is? Yet we continue to program, engage, and educate from within. And we try to improve it, demand from it. And to receive something in return. For all these reasons we demand.

As I have been researching and writing this essay, I also have inhabited the acute contradiction of our times. Important internal and external work at Brown University has led to recent returns by the Lindeman family, billionaire art collectors, of objects that date back 1,200 years from the Khmer Empire, to Cambodia. The story of the looted objects first purchased from art dealers and that have now been returned to the Cambodian government is extraordinary. As is the fact that Cambodian investigators first saw the items in the background of an Architectural Digest feature story that showcased the Lindemann mansion.16

I’ve been asked: What should be done with the stolen artifacts? I say: Give them back. I’ve been asked: What should be done with the museum spaces? I say: Program and distribute the funding to artists, especially disenfranchised queer and trans artists of color, and most of all to those outside the institution and inside the spaces of so much resource theft. I’ve been asked: Who should sit on the boards? And I say: Don’t make trustees out of carbon and oil kings. Or out of the punishment monarchy. Divest in those who invest in the military and police. Divest and unbuild to re-invest and make anew in the otherwise. But it doesn’t mean I don’t live these difficult and uneasy contradictions each day and in every place I work, inhabit, occupy, and endure. Like in Cuthand’s reflection, I, too, wrestle with these contradictions and continually unsettle. I engage the methods I know best: to unearth the deep relations of extractive architectures.

Macarena Gómez-Barris, Where Memory Dwells: Culture and State Violence (Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007); Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone: Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); and Macarena Gómez-Barris Beyond the Pink Tide: Art and Political Undercurrents in the Americas (Los Angeles and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018).

See Trask’s book From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai’i (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1993). An April 2022 report by Stockholm International Peace Research Institute found that military expenditures globally had hit record levels, with the five largest spenders in 2021 being the United States, China, India, the UK and Russia. That year, global military expenditure hit $2.1 trillion. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, “World military expenditure passes $2 trillion for first time,” April 25, 2022. See ®

In Where Memory Dwells, I discuss memory symbolics as art and expressive forms that enliven remembering and witnessing the past in fields of collective action.

See Kirsty Robertson, Tear Gas Epiphanies: Protest, Museums, Culture (Montreal: McGill–Queen’s University Press, 2019).

For an excellent analysis of the rise of petro cultures in the US and its imbrication in our current global petrol-based economy see Matt Huber, Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom, and the Forces of Capital (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Eduardo Galeano, The Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, 25th Anniversary Edition, trans. Cedric Belfrage (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1997).

See Michael T. Klare, Resource Wars, the New Landscape of Global Conflict (New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2002), and my book The Extractive Zone.

See Greg Grandin’s, Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2009).

See my first book, Where Memory Dwells and Micol Seigel, “Nelson Rockefeller in Latin America: Global Currents of US Prison Growth,” Comparative American Studies 13, no. 3 (2015): 161-175.

See Marie Stokkenes Johansen, “The Bond Between Art and the Oil Industry,” Contemporary Art Stavanger Journal, January 29, 2021. See ®

See Simon Romero, “Coup? Not his Style. But Power? Oh, Yes,” New York Times, April 28, 2002. See ®

See Hakim Bishara, “Washing their Hands with our Blood: Activists on MoMA Trustee’s Dominican Republic Gold Mine,” Hyperallergic, June 6, 2021. See ®

I discuss this in depth in my book The Extractive Zone.

See Ruha Benjamin, Race After Techology: Abolitionist Tool for the New Jim Code (New York: Polity, 2019).

Veronica Gago, The Feminist International (New York: Verso Books, 2020).

See Tom Mashberg, “Lindemann Family Returns 33 Looted Artifacts to Cambodia,” New York Times, September 12, 2023. See ®.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

Category

Subject

This essay was originally commissioned by Strike MoMA as part of its mobilization efforts.

.png,1600)