In 1963, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (1959–1990) called Singapore a “society in transition,” pushing the country on an upwards trajectory towards modernization and a place on the world stage.1 Now, four decades later, Singapore persists as a divided multicultural society where identity politics and inequality are evident in national policies towards skilled and unskilled foreign laborers. While the city-state pursues economic expansion marked by security, stability, and prosperity, these social benefits are mostly enjoyed by Singaporean citizens, and not equally distributed among its permanent and transit populations.

After the Cold War, Singapore was positioned as an anchor for intra-Asian operations by Western neoliberal democracies such as the UK, US, and Australia. In contrast to countries like Malaysia, where Malay workers were increasingly mobilized by the Malayan Communist party, the Singaporean government established non-communist labor unions with support from the US.2 As Singapore’s urban density increased with rising populations of skilled and unskilled foreign workers, these same workers became a site of contention for politicians, construction developers, and activists in relation to the nation’s economic and immigration policies. Where Singapore’s new buildings and infrastructure represented its financial affluence, the growing body of foreign laborers that built them became stigmatized as the embodiments of Singapore’s “addiction to cheap labor.”3

Today, uneducated workers from Bangladesh, China, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam arrive in Singapore with temporary visas to work in the construction and maritime industries. Around 200,000 unskilled workers are currently housed in forty-three state-regulated dormitories located in scattered urban locations. Overseen by the Singaporean government, these sites undergo frequent legislative changes in response to the evolving needs of employers and migrant workers. Worker housing is often relegated to sites next to petrochemical manufacturing industries, far from central neighborhoods. In the western district of Tuas, for instance, facilities for foreign workers—bedrooms, canteens, markets, communal facilities, and light-rail transportation—are located near the PUB Tuas South desalination plant. Another 95,000 unskilled workers live in 1,200 factory-converted dormitories managed by diverse employers around the city, and an additional 20,000 construction workers are provided with on-site housing by companies trying to reduce costs as much as possible.4

Climate change intersects with the forced displacement of migrants to reinforce existing inequalities of ethnicity, class, and citizenship. Poorly planned and provisional housing for transient workers is erected in a way that prioritizes state and economic efficiency over the living conditions of its inhabitants. Segregated dormitories are designed with little regard for the context of tropical climates, and often lack air conditioning or shaded outdoor areas. As tropical countries cope with hotter temperatures and higher levels of humidity, building standards around climatic design are becoming increasingly important. While affluent city dwellers continue to visit air conditioned spaces around Singapore, the inequity apparent in the design of worker dormitories continues to feed the growing gap in environmental discomfort between migrants and citizens.

By 2030, Southeast Asia’s worker productivity is predicted to decrease by 11% due to global warming.5 Human capital inflected by “Asian values”—namely, the preference for societal stability over personal freedom—is administered at the whims of the Singaporean government, for whom migrants’ labor is essential for the country’s growth.6 At the same time, these migrants are rendered powerless within planning systems that assign reduced living standards to foreign workers. The collision of human capital, climatic design, and migration policies has created an untenable situation in twenty-first-century Asia.

As a result of such collisions, the complex nexus between financial power, industrial manufacturing, and unparalleled construction growth has also served to widen the gulf between Singapore’s rich and poor, Chinese, Malays, and Tamils, permanent and transient populations. These socioeconomic and environmental trends converge forcefully in the workers’ purpose-built dormitories (PBDs). In this context, “climatic privilege” is an operative category consisting of power structures, technologies, and legal definitions of residency that determine who may apply for specific types of housing, schools, and jobs.7

Climatic inequalities are not only derived from systems of the technoscientific state. They also become visible at the level of buildings, where regulatory laws and building codes increase the precarity of vulnerable groups like unskilled laborers. In fact, some of the same mechanisms that make Singapore financially secure are used as legislative tools against the legal interests of migrant workers. By coupling financial interests with deliberate urban zoning, both policymakers and construction and petrochemical companies dictate how and where low-wage laborers may live.

Architecture is complicit here in reducing basic living amenities for migrant workers on building sites, in factories, and in petrochemical industries. Not only are air conditioning, shading, or other amenities rarely provided in the design of PBDs, but state legislation limits improvements that would make these buildings more bearable in the tropical heat and humidity in the name of cost efficiency. Born from the merger of corporate and government regulations, the climate inequalities materialized in the designs of worker dormitories facilitate greater exploitation of laborers, who endure hotter temperatures without sufficient legal protection.

Zones of Exemption

The legal jurisdiction to designate residential zones for migrant workers is rooted in Lee Kuan Yew’s efforts to modernize Singapore’s government beginning in 1974. By setting up a “government that runs like a corporation,” Lee transformed Singapore into the “Zürich of the East.”8 School curricula and foreign relations were carefully measured in terms of cost-effectiveness. Known as a democratic socialist, Lee crafted Singapore into a “rugged society” where multinational corporations supplied the island city-state with “capital, expertise, and export markets”—an economic policy that has endured into the present.9

Singapore’s “non-aligned foreign policy” makes it a useful ally to a number of foreign powers.10 Through bilateral trade agreements, it has encouraged Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates to provide crude oil for its local refineries in exchange for their investment in Singaporean industries. Recent estimates for Singapore’s exports are based on growth forecasts of its largest trading partner, China. Oil is also Singapore’s second largest export commodity to the US, valued at US$616 million in 2020.11 Such numbers demonstrate the scale of influence held by petrochemical manufacturers in Singapore. Under Lee, the government also moved aggressively into profitable enterprises by investing in shipyards, banks, hotels, steel mills, and even substantial stock shares of other companies located in diverse sectors.

The city-state approaches to migrant workers, their places of residence, and legal rights as economic assets that require close governance. Government legislation in Singapore standardizes which types of basic services can be provided in workers’ housing, but does so in consideration primarily of potential long-term impacts on Singaporean citizens. Any urgency to act on improvements for foreign workers is weighed against these other, and often contradictory, priorities.

Compared to Singapore, some megacities like Manila are making better attempts to provide environmental comfort for all types of residents in response to climate change. However, “energy poverty”—which goes beyond monetary terms—continues to be a significant problem in Southeast Asia. Access to energy services remains a pivotal issue: some households are unable to tap into an electrical grid or reach markets where they can purchase electrical equipment.12 This trend is exacerbated for rural residents and foreign workers since both groups are unable to choose where they may live in expensive cities like Singapore.

Inequality by Design

The immigration of low-skilled workers remains instrumental to finance and industrial production in Singapore. Not only do migrant workers supply a large source of seasonal and project-based labor, but they are also perceived as a source of human capital that expends a portion of the limited resources belonging to the city-state of Singapore. Foreign workers constitute at least 35.2% of Singapore’s total workforce of 2.99 million as of December 2009.13 In 2019, this figure increased by at least 284,300 workers in total within the construction sector alone.14 As such, worker housing links the large-scale manufacturing critical to Singapore’s economy to the management of migrant populations that is key to government policy. These buildings accordingly fall under the remit of at least four government agencies: defense, environment, labor, and urban planning.

The Employment of Foreign Manpower Act of 2007 and the Foreign Employees Dormitories Act of 2015 are two major legal measures enacted to regulate migrant worker dormitories.15 The latter act pertains to “boarding premises” that provide up to 1,000 beds for residents who are foreign employees. According to the 2015 Act, newer industrial zones must include spaces for worker dormitories and corporate parks, specifically in the technology sector. However, these mixed use zones have not considered the transportation needs of the large numbers of migrant workers who live full-time in these districts. Needless to say, clustering dormitories and industrial parks together on the outskirts of Singapore does not necessarily foster a strong sense of local community for these workers.

Within this context, developers play an active role in selecting key sites for their dormitories. As the second largest operator of dormitories in Singapore and Malaysia, the Westlite company (owned by Centurion) strategically chose five locations across the city and engaged in long-term land tenures for investment stability before 2011. Westlite’s hardline positioning, for example, allows it to keep up with the “increased costs associated with regulatory requirements,” covering at least 28,000 beds for workers. The remaining 4,000 to 5,000 beds in this sector are managed by twelve other dormitory providers, giving Westlite a dominant share of the accommodation market.16 Toh Guan, one of its first dormitories containing 5,300 beds, opened in 2011 as Westlite continued to acquire strategic parcels of land near industrial parks as their portfolio of buildings expanded to the present day.

Some employers shun these dormitories for costly reasons, preferring to house their workers on construction sites in “cheap, makeshift shelters” that are legal as long as they are deemed “structurally safe.”17 Before the National Environment Agency (NEA) and Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) became part of the Ministry of Manpower’s 2014 legislation on worker dormitories, construction companies possessed more leeway to choose any type of temporary accommodations for their workers. Previously, migrant workers could be found living on partially completed office buildings and storing their belongings in unfinished rooms. In an effort to reduce pressures on existing infrastructure in industrial areas with large numbers of worker dormitories, in 2016 the URA expanded the list of industrial areas where new buildings could not be erected.18

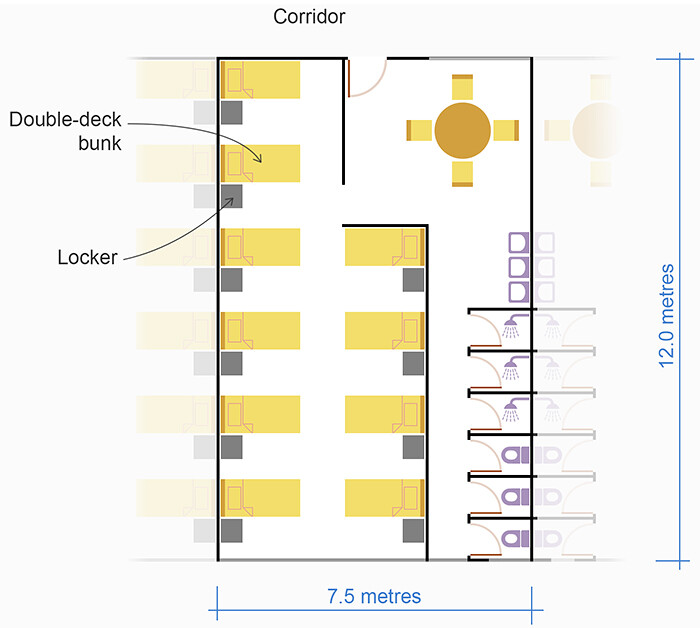

A schematic sketch of a typical room in a modern dormitory, with 4.5 square meters per occupant in a 20-person room, the minimum requirements according to the building code. The sketch is based on dorm visits by TWC2 volunteers and worker descriptions of their own accommodations. Diagram by TWC2 (transient workers count too), 2020.

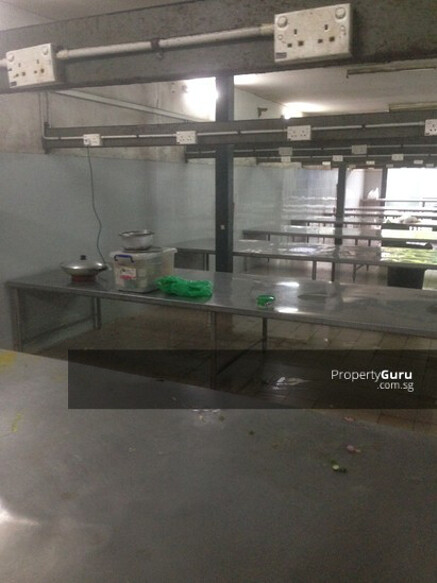

Photo of a Tuas View bedroom, taken by a real estate agent and posted in late 2019.

Photo of a Tuas View wall with a single window, taken by a real estate agent and posted in late 2019.

Photo of Tuas View communal kitchen facilities, taken by a real estate agent and posted in late 2019.

A schematic sketch of a typical room in a modern dormitory, with 4.5 square meters per occupant in a 20-person room, the minimum requirements according to the building code. The sketch is based on dorm visits by TWC2 volunteers and worker descriptions of their own accommodations. Diagram by TWC2 (transient workers count too), 2020.

Meanwhile, the NEA is concerned with worker housing, dormitories, and hostels alike from the perspective of health protections, and mainly addresses “lapses in hygiene that could cause infectious diseases.” Cleaning programs, refuse management system, and hygienic food preparation are closely monitored.19 The environmental guidelines for dormitories mandate a minimum of 4.5 square meters in gross floor area per worker, including basic living facilities, sleeping quarters, kitchen, dining, and toilet areas.20 This type of discretionary authority does not specify design elements such as designated rooms for sleeping or recreation, or circulation spaces like corridors, lifts, or stairwells.

Only the most rudimentary standards are outlined. Workers’ bedrooms should be “adequately ventilated and lighted.” Toilet facilities should include a water closet, urinal, hand wash basin, and a shower room. Cooking areas must be compartmentalized and placed at least five meters away from any external walls, above ground, with a roof overhead, and a raised floor slab set up with proper drainage. There is no mention of electrical outlets for fans or other basic appliances. Cooking areas must, however, contain a proper wash area and refuse bins for waste.21 There are specific guidelines for the management of mosquito breeding grounds. Contractors and developers are “strongly encouraged” by government agencies to provide additional amenities like a sickbay, laundry washing, drying area, and collection points for waste within their compounds. There is no mandate to include air conditioning or a cooling system of any kind.

Built Enclaves, Legal Exclusions

Near the Straits of Johor, worker dormitories in Tuas and other sites around Jurong Island could easily be mistaken for any other industrial district, like the three- to four-story bright blue and neon green prefabricated buildings situated alongside the road on the western edge of the Lion City. Owned by developer TS Group in 2014, the Tuas View Square dormitory is one of the first and largest purpose-built dormitories for foreign workers, home to around 5,000 residents. Spanning 8.4 hectares, the complex includes twenty four-story blocks, with recreational and service facilities including ATMs, an international money transfer service, medical and dental clinic, supermarket, gym, soccer court, beer garden, cinema, barber, clothing shop, and communal cooking facilities. Beyond the diverse amenities of the compound, its residents are paid on the average SG$600 per month as a living stipend on top of their housing costs (as of 2016).22 For a worker like R. Madhavan, who created the short film $alary Day (2020), a portion of his salary (SG$450) is sent back to his family as a remittance. The rest is used for buying groceries, prepaid meals, and topping up his phone card, leaving almost nothing left.23

Like the buildings erected by competitor Anderco, most of the TS housing blocks are built around a core of prefabricated systems. The generic slab buildings are fitted with narrow wall panels and a small number of shuttered windows. Many sleeping areas have only exterior ventilation slats. Bright blue balconies punctuate the railings and structural frames of the housing blocks, the sole component of a colorful visual identity. The migrant dormitory entryways are built as security checkpoints, and the exterior areas of the buildings are completely fenced in.

Inside, as many as twelve men may sleep in a single bedroom, sharing one or two ceiling fans. Shared bedrooms sometimes measure approximately thirty-nine-by-twenty-five feet, and are connected to a communal bathroom with a handful of toilets and sinks.24 The entryway into each unit includes a round dining table with only four chairs. Outdoor dining and cooking areas, with tables and gas burners, are minimally covered and left open to the air at one end. Some passive cooling takes place through the cross breezeways, but without central air conditioning, there is little comfort for migrant workers sleeping in overcrowded prefabricated modules. This is somewhat ironic, given Lee’s promotion of air conditioning as a modern technology that would transform Singapore’s productivity. Furthermore, the accumulation of air conditioners used in signature buildings only expels greater amounts of heat and humidity into the ambient environment where migrant workers toil.

In the process construction and maintenance sector, newer mixed-use dormitories are even more specialized. The ASPRI Westlite dormitory, built in 2018 for SG$200 million, combines housing for 7,900 residents with an integrated training center in Jalan Papan, Jurong East. Here, workers who commute to Jurong Island can save up to two hours per day by completing their subsidized courses and training exercises at home, a measure that not only reduces costs for employers but benefits corporations as well. Newsletters and mass e-mails are sent to workers explaining how much leisure time they can gain by living closer to construction sites. Westlite Woodlands holds weekly yoga classes for workers and sponsors excursions to Universal Studios Singapore and nearby Malaysia. Like other corporations, Westlite uses extra amenities to keep their workers content while living as close as possible to construction sites, keeping overall transportation costs to a minimum.

Worker Happiness?

Recent online advertisements for Tuas dormitory rooms feature slightly blurry photographs taken in cramped, narrow hallways: a communal bedroom with stacked rows of sparsely furnished bunkbeds scattered with random belongings; a wall with single strip window meeting an exposed ceiling—living quarters with harsh lighting, inadequate ventilation, and concrete slab floors. One image depicts the bare efficiency of a communal kitchen, its rows of stainless steel tables equipped with portable burners.25 Many advertisements on Gumtree or CommercialGuru show windowless rooms with holes sawn into the walls for ventilation.

The structure, design, and interior climate controls of worker dormitories should be treated and maintained as national assets. They embody an economic ecosystem rapidly expanding beyond the Singaporean government’s limits, posing a threat of precarity to the financial health of the construction and petroleum industries. But as long as worker dormitories and their government-regulated amenities are considered a privilege, rather than a guaranteed right, then migrant workers will have little recourse to demand better treatment.26

The legal language of economic opportunity used by the Singaporean government cloaks a deeper agenda: without the labor of migrant workers—the “human capital” so critical for the country’s financial security—there would be no one to erect the contemporary skyscrapers that have made the city-state so profitable. The accumulation of migrant workers in Singapore points to the industry negotiations and tradeoffs that Lee Kuan Yew carefully weighed when introducing corporate practices into Singaporean government.

Migrant workers have, meanwhile, been used in self-congratulatory media campaigns for the Singaporean government, where they are depicted as an active and engaged sector of society. The Ministry of Education promotes Singapore as a “global schoolhouse” for English speakers, aiming to attract a diverse selection of international students. Undergraduates from the National University of Singapore (NUS) even volunteer their time to share food with migrant workers.27

Migrant workers are visualized as a worthy social cause, but they are rarely accepted as permanent residents of Singaporean society and certainly, not as Singaporean citizens. In the entanglements between financial stability and urban growth, they inhabit the apex of economic aggregation and human accumulation, where citizenship trumps transitory visas. Even as differential treatment rears its head, the Asian values once propagated by Lee Kuan Yew as a cohesive form of national harmony are now fortified by Singapore’s brand of neoliberal injustice.28

Lee Kuan Yew, “The East Asian Way—with air conditioning,” New Perspectives Quarterly 26, no. 4 (2009): 111–120.

S.R. Joey Long, “Mixed up in Power Politics and the Cold War: The Americans, the ICFTU, and Singapore’s Labour Movement, 1955–1960,” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 40, no. 2 (June 2009): 323–351.

See Alex Au, “The dorms are not the problem,” transient workers count too, May 1, 2020, ➝. Contemporary buildings include Kohn Pedersen Fox’s Robinson Tower, Safdie Architects’ indoor waterfall within the Jewel Changi Airport, Bouygues Batîment International’s modular Clement Canopy, and WOHA’s Singapore Institute of Technology’s campus slated for 2023.

See Lim Yan Liang, “Rethinking Dorms: Next steps for foreign worker housing,” The Straits Times, May 26, 2020, ➝.

Tord Kjellstorm and Bruno Lemke, “Climate conditions, workplace heat, and occupational health in Southeast Asia in the context of climate change,” WHO Southeast Asia Journal of Public Health 6, no. 2 (September 2017): 15.

As a political ideology espoused by Mahathir Mohamed in Malaysia and Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore, Confucianism relinquishes attributes of personal freedom in favor of societal stability and prosperity. These values include social harmony, socio-economic prosperity and collective well-being, academic and technological excellence, loyalty and respect towards authority figures, and a preference for collectivism and communitarianism. Southeast and East Asian countries embraced these values up to until the 1997 Asian financial crisis, where a nation’s culture would determine its fate.

Climatic privilege is a concept derived from our ongoing collaborative project “Climate cultures” between the University of Sydney and National University of Singapore. My colleagues at both institutions (Christhina Candido, Jiat-Hwee Chang, Nathan Etherington, Erik L’Heureux, and Daniel Ryan) and I have been testing this term for a number of architectural contexts in Australia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Some scholars have also traced Singapore’s urban development as a fledgling colony back to the Jackson Plan or Raffles Town Plan (1822). On Singapore and Lee’s economic philosophy, see Louis Kraar, “Singapore, the country run like a corporation (1974),” Fortune, July 1974, ➝.

Transcript of speech made by Prime Minister Mr. Lee Kuan Yew, Queenstown Community Centre, August 10, 1966, National Archives of Singapore.

Ibid. Fortune magazine was quick to report on Singapore’s interest in global petroleum industries: “Singapore goes to considerable lengths to snare key industries. Two small offshore islands were cleared not only of jungle, but also of resident fishermen and their family graves to make way for an Esso refinery and Mobil oil-storage tanks. Thanks to its obliging attitude and central location, the city-state has become the site of the principal refinery complex in the region. Shell, British Petroleum, and Amoco also process oil there, primarily for Japan and other Asian markets. By the end of this year, total refining capacity will exceed a million barrels a day—making Singapore the world’s third-largest oil-processing center, after Houston and Rotterdam.”

On export and import commodities traded between Singapore and the United States, see “Singapore,” US TradeNumbers, 2020, ➝.

Sonal Jessel, Samantha Sawyer, and Diana Hernández, “Energy, Poverty, and Health in Climate Change: A Comprehensive Review of an Emerging Literature,” Frontiers in Public Health 7 (December 2019): 357, ➝.

Yap Mui Teng, “Singapore’s Systems for Managing Foreign Manpower,” in Managing international migration for development in East Asia, eds. Richard H. Adams, Jr. and Ahmad Ahsan (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2014), 220–240, ➝.

Refer to Ministry of Manpower, “Foreign Workforce Numbers,” Government of Singapore, 2020, ➝.

Centurion Corporation Limited, “Oversold and underrated,” financial report, October 2015, 10.

Registered accommodations only cost employers around SG$500 per worker, while unregistered spaces can be as low as SG$80 per worker. On the city of Nusajaya, see: Mimi Kirk, “The Peculiar Inequality of Singapore’s Famed Public Housing,” Bloomberg CityLab, June 9, 2015, ➝; Teng, “Singapore’s Systems.”

Urban Redevelopment Authority, “Circular to Professional Institutes,” URA/PB/2016/14-PCUDG, September 19, 2016, 1.

National Environment Agency, Good Environmental Health Practices for Dormitories and Hostels, Singapore, November 2008.

Urban Redevelopment Authority, “Appendix D,” Amenity Provision Guidelines for Workers’ Dormitories, 2.

See Environmental Health Guidelines for Dormitories, Singapore, August 2010.

On migrant workers’ salaries, see “TWC2 survey: starting salaries for migrant workers flatlined for the last 10 years,” transient workers count too, January 15, 2017, ➝.

R. Madhavan, $alary Day, YouTube, April 25, 2020, ➝.

Refer to the generic floor plan provided by TWC2. See “Covid-19: the risks from packing them in,” transient workers count too, April 3, 2020, ➝.

See Matthew Sacco, “What Does Singapore Owe its Migrant Workers?” Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, February 10, 2016, ➝. Ministry of Manpower has instituted an app called DormWatch where workers can log complaints about their living conditions and report defects and broken equipment to dormitory operators. For resources on organisations advocating for migrants’ rights, see: Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME), ➝; transient workers count too (TWC2), ➝.

NUS Students’ Union,“Makan with Migrant Workers,” Facebook, January 29, 2019, ➝.

Thanks to Nick Axel, Daniel Barber, and Erik L’Heureux for comments on earlier drafts of this essay.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

.png,1600)