Researchers, activists, and citizens are speaking more and more about “getting away from the system of production.” The goal is no longer simply to replace the owners of this system, as it was in the communist era, by giving the proletariat ownership of the “means of production”; it is also not to more equitably distribute the profits of this cornucopia, as the social democrats have always tried. No, the demand is becoming more and more insistent, more and more urgent, and, especially since the public health crisis, more radical: it is the system of production itself that we must now get away from—and the very concept of the production of goods.1

But what are we really trying to say by this? In what way is it a revolutionary pursuit? Why, for that matter, should we deprive ourselves of production, now that each of us lives surrounded by all the goods we’ve desired for so long, the possession of which enchants us? What is the reasoning for such an injunction now, as an economic crisis, on the heels of the health crisis, throws onto the street millions of unemployed people? Why would we not rather see the “picking up of production” as quickly as possible?

There is certainly something rotten in the kingdom of production. As if it were, deep down, irreformable. As if, the opposite of King Midas, it destroyed everything it touched—after having turned it into gold. It seems, in fact, that the ecological mutation—which follows, surrounds, precedes, exceeds the health crisis—demands that we ask the question of an alternative to production and its role in a system that can be neither reformed nor revolutionized, but instead always carries on in the same direction and reinforces itself—as we risk seeing, alas, with the “economic resurgence” after la Covid (the feminine article is mandated by the Académie Française).

For a few years now, I have tried to stress the contrast between the system of production and what I suggest calling practices of engendering. Why? Because to speak about plural practices is to already remove oneself from the dangerous hegemony implied by the notion of a singular system: faced with a system that is too complete, too coherent to be modified in pieces, one can only bend to it, or dream of bringing it down entirely; to confront it is to cut off one’s own arms and legs. In addition, to speak of engendering is to establish a distinction between the act of producing—which attributes the undertaking and the central role to the human agent—and the act of contributing to the generation—which shifts the center of gravity onto other modes of action.

One could dispute the choice of this expression, but I find it has three advantages that at least justify using it to open the discussion.

Engendering contains gender—and this is no coincidence. The repression of all that has to do with genesis, care, and the maintenance of lifeforms is tied, in Western history, with elision, eviction, and even the persecution of the feminine. There is thus a compelling interest in critiquing the system of production through the lens of the immense ongoing project of feminism and, in particular, in understanding the invention of the economy as an unfolding masculinization—whose history is now partially complete. To “get away from” the system of production, is, by definition, to get back to the question of gender and the allocation of affects and expertise between the sexes. It is also, more deeply, to reformulate the question of origin: from whom and from what are humans born?

Another advantage of speaking in terms of practices of engendering is that it forces us to situate in time and space the particular enterprise of systems of production.

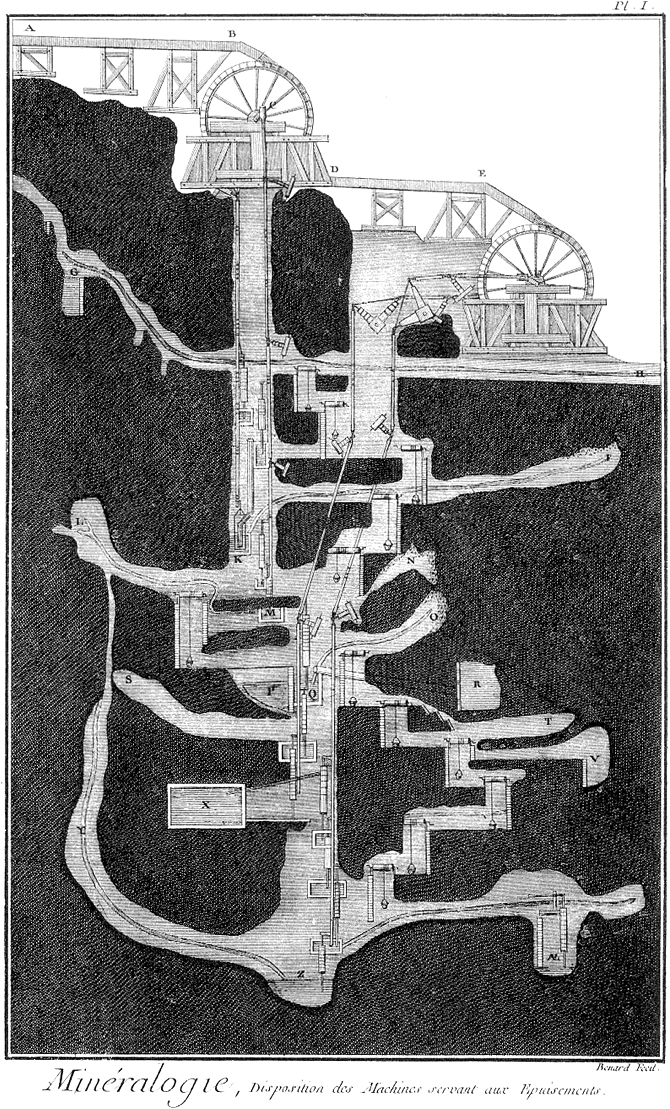

Despite their apparent expansiveness, there is nothing universal about them. Anthropologists have worked hard to make readers in industrial societies understand just how inappropriate it would be to take the gardens of the Amazonian Indians, the farming of yams in New Guinea, the breeding of horses in the steppes of Tibet, and turn them into “more or less productive acts,” inserting them into a “system of production.” It’s not for lack of trying, of course. Economists, colonial administrators, and sociobiologists have indeed tried to make each of these practices of engendering “fit into” a kind of faux-system of production, but, most often, the result has been to destroy such practices or render them incomprehensible.

We have to accept it: since the dawn of time, communities have procured their own wellbeing, have known relative abundance, have enriched themselves and prospered without their practices being qualified as the “production of goods.” On the contrary, resisting the pressure of economization has been essential. Hence, the idea that “we are not producing, we are participating in the engendering of combinations of lifeforms” would not be a bad way to describe that resistance.

The third advantage of this contrast is to embed the act of production within practices that render the act possible, but whose importance it otherwise denies.

The universal resistance to the notion of production, in fact, is not linked only to exotic terrains, to ancient societies, or to the margins of industrial societies. The sociology of work, and of organizations, has shown, for a long time now, how many micro-inventions have been necessary to advance an assembly line of cars or to carry out an order. Planning offices might be ignorant of what happens on the assembly line; the workers know perfectly well that the assembly lines, as roboticized as they are, would jam in a few minutes without their intervention. More generally, there is not a single course of action that does not require, at some point before it can be brought to fruition, a restart in each of its parts through an innovation, no matter how minuscule. All production unfurls, in fact, because around and within it, countless practices of engendering allow us to see it through.

Thus, what we call the “system of production” is only ever one single part of what renders it possible, or, to use a perfectly suited word, its viability always and still today relies on what it cannot “take into account.” What one says of the invisible feminine work that renders visible production possible must also be said of the very notion of the “system of production”: it is, by definition, a form of organization that ignores or even denies the conditions through which it is accomplished. To return to an expression from Matthew 2.1, “so the first shall be last and the last first” (or a phrase popularized in France during the pandemic, “pas de premiers de cordée, sans premiers de corvée”). Or, to put it in yet another way, we call the “system of production” that which manages to extract a value of engendering that it doesn’t recognize—meaning a surplus value of engendering that is surreptitiously added to the surplus value of the labor theory of value in traditional analysis (and which, for that matter, explains its nature).

Evidently, these three elements must be further developed, but if I consider them as established, it’s because of the irruption in politics and in the media of what we could call “disturbances in the engendering.” I find it very indicative that, from the far right to the far left, political sentiments are no longer expressed in terms of their relationship to production (who from the State or from the Market should triumph; how to more equitably distribute goods; must we reform or revolutionize the economy; how to guarantee continued progress; whether to allow “the reopening”, etc.) but in terms of the risk run by the genesis of lifeforms. As if it were indeed an existential question, a question of the continuity of forms of “generations” that has become the heart of public life.

Never during the “Trente Glorieuses” would we have conceived of an activist movement that would be called the “Extinction Rebellion”—added to the rebellion of the former far left is henceforth this new shadow cast by the new risk of extinction. The temporal horizon has been completely modified by it. On the other side of the political spectrum, how can we not be startled by the appalling effort put into the fight against “gender theory” in the French academy—in addition to those against abortion and “marriage equality.” The threat of the return of gender is perfectly clear. As for the far-right fear of “the Great Replacement,” it seems to be the ideal symptom to perfectly designate the abyss of extinction. And what about the staggering spread of theories of collapse (oddly referred to as “collapsology”), which influence just about every political position? As if the risks run by the “genealogical principle” had become the common vulgate and yet remained hidden from the general public.

Even the most reasonable iterations of ecologization use expressions such as “sustainable development,” “short circuits,” and “circular economy,” which all highlight the need to maintain the continuity of exterior “resources” used on top of production itself. More striking is the return of the question of land, of earth, of territory both in the most reactionary forms—the neonationalist imposition of borders of all kinds—as well as in the most progressive demands—the irruption of Gaia. In all their possible forms, the earth, the land, the planet emerge as “factors of production” that had been completely forgotten during periods of modernization.

Brusquely the question returns: “What earth will I be able to live on, and my descendants?” a question that echoes simultaneously on the left, in the center, on the far left, on the right, and on the far right. Even as we believe there to be a complete dispersal of political opinions, attention has unanimously shifted toward a new subject: the end of the world. In this sense, it is not certain that we must seek an alternative to the system of production: mentally, we have already gotten away from it. Except there is no shared definition of the alternative. That’s what justifies exploring the expression “the practices of engendering.” Is it a suitable way to bring about this new space of political representation? As if the opposition between practices of engendering and the system of production would be able to serve as a compass for us to identify the new political polarizations? It seems to me that these questions deserve to be posited now at a time when the world has witnessed, if not an end, then at least a brutal and completely unexpected halt of the entirety of its economy—before throwing itself, just as blindly, into “picking up” production again.

This essay was originally written for isolarii, as a foreword to Salmon: A Red Herring by Cooking Sections. isolarii is a series of island books, released every two months by subscription.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

Translated by Emma Ramadan.

This essay was originally written for isolarii as a foreword to Salmon: A Red Herring by Cooking Sections. isolarii is a series of island books, released every two months by subscription.

.png,1600)