Precarious Entanglement

In the Anthropocene—the current terminal period of neoliberal capitalism marked by climate change, environmental degradation, and social-political unraveling—calls to rethink human life abound. In response, a powerful subframe of Anthropocene theory—what we might name “precarious entanglement” or “dwelling in the ruins” thinking—forwards one way of doing so. For proponents of this perspective, the infrastructures, promises, and aspirations of modernity are seen as ruins themselves.1 To think otherwise would be to miss the lessons the Anthropocene holds for us: modern humanism and attendant ideas of progress, hubris, and freedom were an error, and now drive current devastation. Humanity must, this narrative insists powerfully, be humble.

“No more agents of history. We all agree on that,” argues sociologist Bruno Latour, whose work perhaps most fully fleshes out this narrative.2 Reversing the modern story of human freedom as a matter of rising above, separating from, or hubristically trying to transform the world, this line of Anthropocene thinking argues its inverse: that subjection to volatile earth forces and entanglement amidst ruins are the real nature of human existence. This entanglement in social-ecological-technological relations, once elided by modern thinking, is not to be escaped but to be embraced, argues philosopher Timothy Morton; such loops, he maintains, are our “fate” and “destiny.”3 Seeing ourselves within complex systems to which we are bound reveals that rather than makers of worlds, we are defined by precarity. Instead of holding on to hope or dreams of a “happy ending,” we must now learn to survive, to use anthropologist Anna Tsing’s terminology, “in capitalist ruins.”4 The perfect image of our new earthbound existence, Latour says, is the brutal ending to Béla Tarr’s film The Turin Horse:

In the final tempest of the last days of Earth, father and daughter decide to flee their miserable shack isolated in the middle of a desperately parched landscape. With a sigh of relief, the spectator sees them finally going away, expecting that they have at least a chance of escaping their diet of one potato a day. But then, through a reversal that is the most damning sign of our time, a reversal that I don’t think any other film has dared show, instead of moving forward to another land, one of opportunity, full of great expectations, full of hopes (remember America America), we see with horror that they come back, exhausted, despondent, bound to their shack, resuming their old even more miserable life until eventually darkness envelops them in its shroud.5

This reading of the Anthropocene, political theorist David Chandler argues, is itself “increasingly affirmed as a positive and enabling opportunity” to overcome modernist frameworks and embrace the actual nature of life: precarious survival amidst entangled ruins.6 What is affirmed is the apocalypse that is capitalism at present, the very conditions that define the Anthropocene. In making explicit what is often implicit in neoliberal governance approaches—forwarding images of life as insecure, apolitical, and hostage to volatile systems—precarity-entanglement theory limits itself to thinking through what exists rather than exploring ways to refuse or change it.7 Works in this vein frequently deploy a universalizing “we” whose sins and pride have brought on the Anthropocene.8 The wreck of the good life, the postwar period of high consumption and wages in the West, is normativized and deployed as an effigy of excess, rather than what it was: a brief postwar apparatus, which resulted from pitched workers’ struggles in the twentieth century, and that was ultimately tenuous and uneven. Described in dramatic prose is a new “we” of the Anthropocene that will wander in the wastelands, embracing its precarious and diminished existence, much akin to the life many of us are already living in the early twenty-first century. In a conservative move, this narrative is abdicating human agency, experimentation, and radical challenges to the social order in the name of accepting “our” fate. But, as systems technology analyst Venkatesh Rao recently stated:

It’s funny how people think a post-apocalyptic landscape will be relatively flat socioeconomically. At most they think there will be small-scale warlords or Dunbar-scale anarchist communes. No. There will be deathstar billionaires with private armies and narrow-deep tech stacks.9

Constraining human being to the is—precarious survival amidst entangled ruins—rather than the possible contributes, intentionally or not, to the already-omnipresent sense that what is, is all that is possible, and renounces hubris and audacity at a moment when poor and working-class people seriously need these qualities.

Disentanglement and Delinking

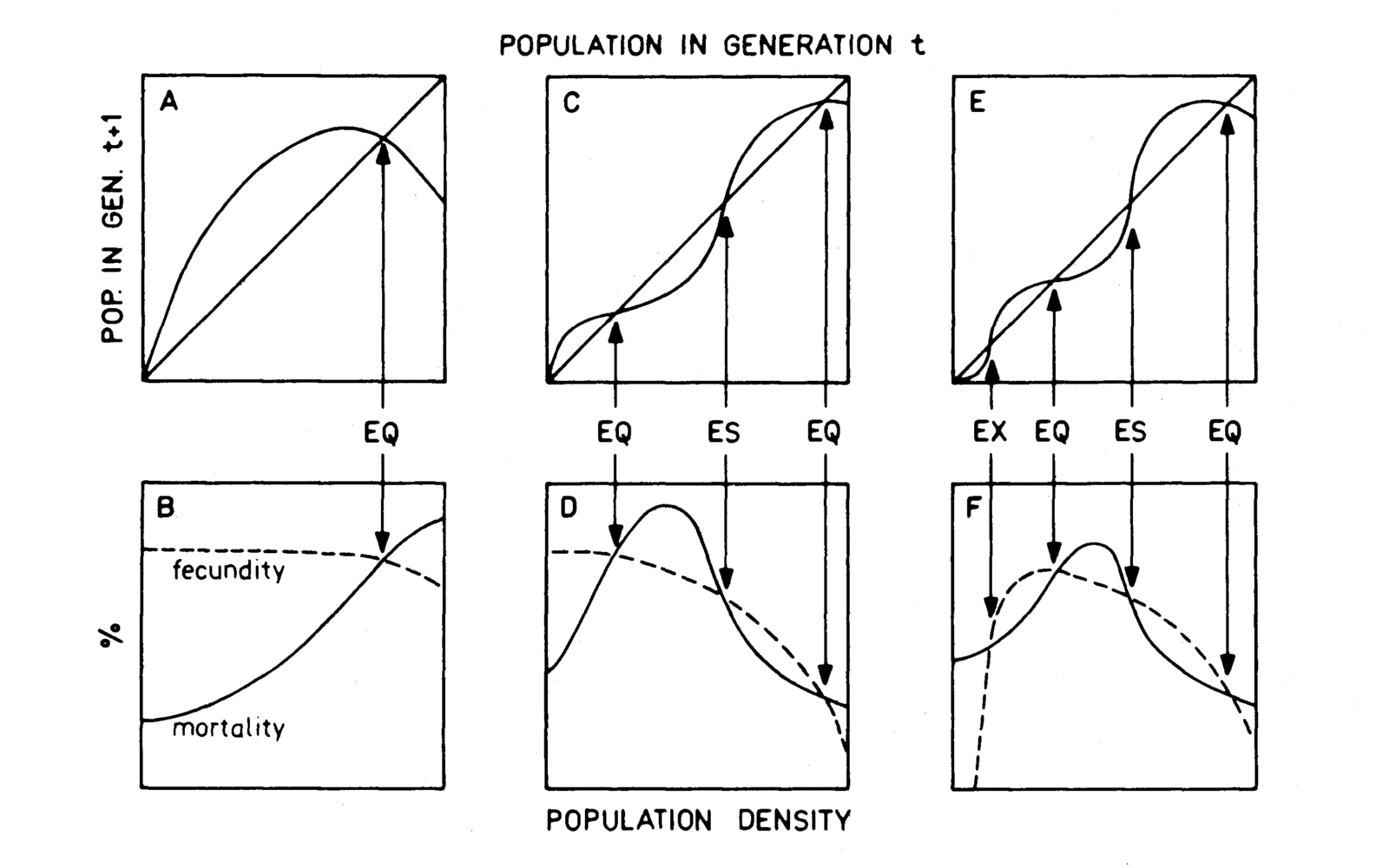

Ultimately, this particular version of Anthropocene thinking fails to capture many of the characteristics and possibilities of the present. By this I do not mean that the current moment is not marked by entanglement. On the contrary, defining and administering life cybernetically in terms of information, feedback, and non-equilibrium interconnection—dismantling the modern subject—has been central to western neoliberal governance for decades.10 Post-September 11, securing interconnected critical networks came to be seen as especially paramount, with American military analysts like Thomas Barnett dividing the world into a “functioning core” and a “non-integrating gap,” the latter defined as “disconnected from the global economy and the rule sets that define its stability.”11 “Eradicating disconnectedness,” argued Barnett in his much-discussed The Pentagon’s New Map, “therefore becomes the defining security task of our age’’12 with failure or refusal to integrate into the global economy and its rule sets enforceable by military action.

From Lagos to New York, urban planners and governments have more recently emphasized connectedness as key to building resilience to climate change and its effects.13 Originating in cybernetics and ecology in the 1970s, resilience is both an ontology and design practice based in systems thinking, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of the social, ecological, and technological.14 Whereas modern forms of administration were based in city/nature binaries and sought to eliminate volatility and risk, resilience is a governance paradigm that welcomes entanglements, understands instability as inevitable, and views cities as coupled social-ecological-technical infrastructural systems that must develop their capacity for absorbing turbulence.15 In resilience approaches, entanglement is thus viewed not only as politically mandatory (as for early 2000s geopolitics) but also ontologically natural: a corrective to erroneous modern ways of thinking.

However, while entanglement is increasingly celebrated, we are also witness to some of its opposite. In the United States, one might observe that there seems to be growing tendency toward “delinking” or “islandization” in response to Anthropocene conditions and events. For example, politicians promote ever-more securitized borders and walls as a manipulative solution to the suffering of working-class people. The very wealthy detach their stacks and supply chains, shore up urban networks against climate change, or disconnect from the same social media they own, while also preparing infrastructure for bigger moves in the future to secure themselves and their forms of life. This may be seen as the Anthropocenization of what historian Nils Gilman calls the plutocratic insurgency that has been underway for decades; a revolt by capitalist elites against the confines of modern postwar territorial power configurations.16 In this insurgency, the rich seek to detach themselves legally and infrastructurally from what Gilman terms “social modernism”: an ideological and institutional formation centered around the nation state as a provider of welfare and economic growth.

Along with off-shore tax havens, Fourth Industrial Revolution modes of labor management, and gutting the West’s working-class and welfarist structures, a key component of the plutocratic insurgency is the creation of enclaves like those documented by Mike Davis.17 “These islands of elitism,” explains Gilman, “are designed to be largely self-sufficient in their ability to deliver health care, food, security, education, entertainment, etc. to their residents, even as they sit amid seas of social misery…From the point of view of the denizens of such communities, the primary function of the wider society is to serve as a source of cheap, servile labor, and as a well of resources to be looted.”18 But gated communities, Gilman further argues, “are merely an example of a broader pattern, in which economic, social, or political enclaves are carved out of a national state and enabled to play by a fundamentally different set of rules from the surrounding territory.”19 Taking this forward, Kanye West recently floated “building a fireproof community” after he and Kim Kardashian hired private firefighters to save their $60 million California mansion during the 2018 California wildfires. Meanwhile, the Seasteading Institute, founded by Milton Friedman’s grandson and originally funded by Peter Thiel, is exploring how to set off a “Cambrian explosion” of autonomous artificial floating cities starting in the Pacific Ocean. In the Institute’s eyes, seasteads are a solution to sea rise as well as what they see as the domineering overreach (read: taxation) of existing governments—a way to “liberate humanity from politicians.”20

These earth governance efforts exist alongside private space colonization projects couched as an escape hatch from an increasingly degraded earth.21 Elon Musk has built and successfully tested rockets on which SpaceX intends to send humans to Mars by the mid-2020s (NASA plans to land astronauts there by 2033) and predicts beginning colonization as early as 2025. Most Left commentators cynically scorn such space ventures.22 However, it is understandable how others might see in them a worthy human venture, one that current and future generations might find actually desirable, not least because it might offer escape from the social carnage of neoliberalism’s cataclysmic continuation on earth. There is nothing necessarily wrong with imagining oneself in the shoes of the first humans to see Mars’s surface with their own eyes, descending from a rocket doorway to touch the planet’s rocky red crust with their own feet. Just like the writings of science fiction author Steven Erikson, commercial space ventures contain their own poetics: the desire to go where no human has gone before; find other life; or sink into the stars at warp speed.23

In the more pragmatic vision of the world’s on-and-off wealthiest person and Star Trek fanatic Jeff Bezos, the only way for poor and working-class people to get to space will probably be as free labor in one form or another. As Bezos recently described, with resources on Earth running out, “space is the only way to go.” Rather than colonizing Mars, though, Bezos plans to build artificial worlds—O’Neill cylinders rotating to create artificial gravity—orbiting Earth and able to support one million people each.24 Some of the cylinders will be agricultural areas irrigated by drones, while some will be cities and others more recreational.

“What does architecture even look like when it no longer has its primary purpose of shelter?” asks Fred Scharmen.25 Like “Maui on its best day, all year long. No rain, no storms, no earthquakes,” Bezos responds. Earth, he envisions, will be rezoned as a residential and light industrial zone.26 “We send things up into space but they are all made on Earth. Eventually it will be much cheaper and simpler to make really complicated things, like microprocessors and everything, in space and then send those highly complex manufactured objects back down to Earth, so that we don’t have the big factories and pollution generating industries that make those things now on Earth.” And as to the question of “who is going to do this work?” Bezos concluded: “not me,” and gestured to a group of school children in the audience wearing shirts from the children’s club of his space company, Blue Origin. “You guys are going to do this, and your children are going to do this.”27

Human Agency: A slender air-bridge to the possible

It is increasingly important to refute assertions—both those of governments and some critical theory narratives—that nothing else is possible. Both literally and figuratively, “this” world is actually not the only world there is. Much is actually possible. The first grunt labor force sent to Mars could blow up the return Starship™—gone Croatan, albeit on the red planet. Still, beyond contributing to the present shredding of the social fabric or desperately flinging oneself against it in vain, it can be extremely difficult to imagine what liberation in the Anthropocene might look like, especially for the poor and working-class. To say anyone knows the answers to the unbelievably complex problem of contemporary neoliberal capitalist society would be disingenuous. To say that a preidentified system would provide a better world seems even more off, especially considering the outcomes of such projects throughout the twentieth century. We cannot imagine what we cannot imagine. If the emergence of the Anthropocene tells us anything it is that we need a break with existing structures and institutions and ways of thinking, perhaps including ones that have risen so recently to hegemony in the epoch’s name.

This need for a break is felt widely. Eco-cybernetic entanglement, precarity, and lack of agency are circumstances in which much of the population lives and not by choice. Rather than celebrating Anthropocene conditions, it is worth considering seriously that an equally descriptive image of the present is that of the current order’s structures on fire. This zeitgeist was well-summarized in political scientists Michael Bang Petersen, Mathias Osmundsen, and Kevin Arceneaux’s recent survey, covered by the New York Times with alarm, which reported highly affirmative responses to statements such as: “When I think about our political and social institutions, I cannot help thinking ‘just let them all burn’” (40% agreed); “We cannot fix the problems in our social institutions, we need to tear them down and start over” (40% agreed).28

This sentiment is part of the attraction many Americans have to apocalyptic movies and TV: the end promises an escape from the present order. Take, for example, the once extremely popular TV series The Walking Dead, which during its golden age—season 4 (2014)—was the most popular show for Americans aged 18–49 (15.7 million people watched the season finale). Episode “Still” opens with a survival skills montage of characters Daryl Dixon (grizzled crossbow-toting fan favorite whose face is featured on “Don’t Mess with Daryl Dixon” t-shirts sold at Walmart) and Beth Greene (blonde, Christian, suburban) collecting tools, trapping animals, and roasting snake. Devastated by the recent murder of Beth’s father and loss of their band of companions, the pair wander a zombie-ravaged landscape. Inside an abandoned country club where they search for bottles of liquor, Daryl discovers piles of money. Falling to his knees, he shovels the bills into a duffel bag, frantically acting on old impulses. Later, they hole up in an abandoned rural house. Car parts and old tires litter the yard. Inside, cigarette butts overflow plates atop a junk store kitchen table. On the porch they drink their found moonshine and share stories from their pasts (while Beth’s sheltered upbringing is known, Daryl’s “before” story has until this episode remained unknown).

“Home sweet home,” says Daryl, reminiscing to Beth how he grew up in a house just like this. He recounts how his abusive racist father would place jumbo, plastic, bra-shaped ashtrays on the TV and use them for target practice, sitting in his underwear drinking in a dumpstered camouflage La-Z-Boy. “You want to know what I was before?” he asks Beth. “I was nobody. Nothing. Some redneck asshole.” “I’m just used to it, things being ugly. Growing up in a place like this.” “We should burn it down,” Beth suggests. Beth too has experienced great pain and loss and is ready to leave the past behind in her own ways. They gather the money they’d hoarded—valueless now as money anyway—and the alcohol with which they’d tried to drown their pain and use them as tinder and fuel to burn the house down. In an extraordinarily beautiful scene—which reverses Latour’s Turin Horse-inspired vision—Beth and Daryl, their faces lit up by flames, point their middle fingers at the ruined house, turn their backs and walk into the night.

It’s not that a better world awaits ahead, and the scene is not triumphant. But to paraphrase Beth, at least you’re not living how you used to, not anymore. This version of the apocalyptic is powerful and popular because it offers a way out of the crushing hopelessness and the impossibility of becoming something or someone else that many poor and working-class people in America feel. Or at bare minimum, a proper response to the structures that create these conditions.

Daryl’s past—represented by the dilapidated manufactured home—offers an image of the rural poverty across the American hinterlands, where unemployment and debt are extraordinarily high and “deaths of despair” (suicide, drug overdose, alcoholism) common.29 Far from the spaces of academic theorizing, such “ruined” places represent the much broader death of the so-called American dream, the sum of the post-1970s decades of revanchism and counterrevolution waged via deindustrialization, wage cuts, urban crackdowns, hyperincarceration; all strategies flanked by a massively increased wealth gap and soaring profits for the very wealthy, now augmented by ecosystemic collapse. Daryl and Beth embody a fictional response to a certain experience of this. But such imaginaries only echo larger scale, real world responses to other, differently situated experiences which have been launched in recent years from America’s impoverished cities and suburbs—such as Ferguson, Missouri—by humans sick of being dehumanized by the never-ending police shootings of African Americans, ghettoization, and economic precarity.30

In spite of theoretical prescriptions to the contrary, we need ways to pry open the walls closing in around us (walls around the imagination, walls between the now and the future, between peoples). Toward this end, Alfredo Bonanno once described insurrection as an air-bridge to the unknown, a non-rational breaking through the structures of the present—wage work, for instance—to a space of the possible in which we might see in new ways. “A slender air-bridge between the tools of the past and the dimensions of the future.”31 Rather than celebrating the ruins or qualities of entanglement and precarity imposed by governments and companies, perhaps building these air-bridges might have something to do with delinking. This can mean detaching, as theorist Eva Haifa Giraud suggests, from structures and situations which strangle us, to reweave others, according to other priorities.32 Perhaps delinking as a liberatory—not resentful or conservative—political matter will also involve both reconsidering what building power today means and working towards freedom as a serious and urgent goal, even (and especially) as the old orders shred themselves apart.

Here we might note, in America at least, the growing normalization of once-outlier activities amongst growing numbers of working-class individuals and families. Examples of this include learning survival skills, building local infrastructures (wireless mesh networks, food production, whether farming or engineering protein bars, etc.), and taking up physical fitness regimes.33 Such activities are representative of an increasingly widespread desire to decrease dependency and take back some degree of power over one’s life and abilities—to reappropriate one’s means of existence, even if the only time to do so is found during lunch breaks. Yet placed alongside the scale, vision, and material means of delinking activities of the world’s very wealthy and the force they mobilize, these scattered efforts too often seem to reflect a powerlessness—an inability to build real power or autonomy—rather than the opposite.

Life exigencies and lack of resources often mean that, at best, such practices result in an increased preparedness to survive the next Coronavirus or hurricane (no minor feat itself of course), in a time where the definition and horizon of life has become “normalizing survival.”34 Still, even prepping is often animated by important questions such as how to help oneself and others and how to not be hostage to relief agencies, FEMA camps, or governments that disdain whole populations. How to save your family from sleeping on a gym floor, like the Kims in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite? How not to allow oneself to be reduced to scrounging for the last can of beans at the panic-ravaged grocery store? How to take care of oneself and one’s own communities—the things and beings you love? Such questions are a pragmatic and existential matter of refusing to be dependent on corporations and algorithms. Addressing them also opens up much broader horizons.

As the Anthropocene progresses, will emancipatory trajectories of delinking take shape at a comparative scale and depth of power to those of the planet’s ruling classes? Will the epoch be marked by a widespread movement of peoples delinking from dehumanizing structures to create other, rich, unbounded territories, ones infrastructurally and subjectively capable of deciding how to live on their own terms? Using recent work by geographers on the concept, “territory” here might be thought of less in terms of a two-dimensional bounded area and instead as heterogenous, emergent assemblages on land or sea; powerful “volumina” made of their own technologies of living, ways of moving, geopowers, and relations with humans and nonhumans.35 Although it is an antagonistic concept, “territory,” philosopher Elizabeth Grosz writes, is also “artistic, the consequence of love not war, of seduction not defense.”36

It’s impossible to know in advance whether this would lead to more livable futures. But surely exploring the possibility offers a more promising direction than affirming precarious entanglement and abdicating human hubris to the rich. Delinking and relinking on one’s own terms are not techniques that conservative forces monopolize. However difficult it may be to explore this direction, given that most lack a financial or territorial base to begin from, it seems crucial to build material power. But then again, maybe some zoomer will say this is an antiquarian modality; that more power can be found enmeshed in ethereal flows accessible alone in one’s bedroom on a laptop (whether using Google or Tor). For some this might be unacceptable or at least not enough, but that doesn’t make it wrong.

Precarity-entanglement thinking recognizes something important about the Anthropocene: we require new ways of thinking and living. But the task of thought should never be to instruct others in how to live, to provide universals to define life, or to flank governmental assertions that “nothing else is possible” other than the resilient continuation of existing structures while the world burns and floods. Taking the claim that old world is ending seriously opens up much broader horizons. The end of the “one world world”—or what I call the Anthropocene’s “back loop”—is not the time for reasserting new universal definitions for what life should be, but for reaching out into the infinite range of what we and others might make it.37 Just as scholars such as Clive Barnett and Stephen Collier have argued against reductive or ontologizing critiques of government, so too is there a need for critical Anthropocene thinking to resist this approach.38

Acknowledging that the world is not there “for us,” that the earth has its own intractable forces and autonomy, need not require as its corollary to sink into self-hatred or disavowal of human capacities. Surely there are other possibilities beyond this false binary that some versions of Anthropocene thinking tether human being to. As Chandler suggests “perhaps it is a false and forced choice to choose between ‘the human’ and ‘the world’? Perhaps rethinking modernity does not necessarily involve the refutation of any possibility of political alternatives other than those based on accepting our newfound fragility and vulnerability?”39

At a time when human power and hubris have become objects of disdain for some, it is important to insist on its critical importance in the Anthropocene. One could look back to a vast and varied range of hubristic human efforts, with some dominating nature or oppressing populations and others embodying collective struggles for freedom. But emancipatory struggle is not an object of remembrance. Rather, it is a basic human need elaborated in ever-new ways. Thus, it is fitting and appropriate that the 2010s opened and closed with global waves of anti-government uprisings (although resistance at the decade’s close was notably subdued in the US). What’s needed now is a hubris proper to both the Anthropocene and the subjects trying to escape from it. Without such a hubris, without the embrace of profound experimentation with existence, we cede the future and our lives to the billionaires and petty warlords, technocrats and politicians.

Stephanie Wakefield, “Infrastructures of Liberal Life: From Modernity and Progress to Resilience and Ruins,” Geography Compass 12, no. 7 (2018).

See Bruno Latour, Isabelle Stengers, Anna Tsing, and Nils Bubandt, “Anthropologists are Talking—About Capitalism, Ecology, and Apocalypse,” Ethnos 83, no. 3 (2018): 587–606; Stephanie Wakefield, Anthropocene Back Loop: Experimentation in unsafe operating space (London: Open Humanities Press, in press).

Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016).

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016), 8.

Bruno Latour, “Facing Gaia: Six Lectures on the Political Theology of Nature,” The Gifford Lectures on Natural Religion, Edinburgh, February 18–28, 2013.

David Chandler, Ontopolitics in the Anthropocene: An Introduction to Mapping, Sensing and Hacking (London: Routledge, 2018), xv.

See Andreas Malm, The Progress of This Storm: Nature and Society in a Warming World (London: Verso, 2018); Brad Evans and Julian Reid, Resilient Life: The Art of Living Dangerously (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2014).

Scholars have criticized the Anthropocene extensively for its invocation of a single figure of Man (or Human or Anthropos), its erasure of race and gender difference or its elision of the fact that the destruction now wrought by “humanity” is in fact caused by the actions of a very small percentage of wealthy people. See, for example, Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019); Andreas Malm and Alf Hornborg, “A Geology of Mankind? A Critique of the Anthropocene Narrative,” The Anthropocene Review 1, no. 1 (2014): 62–59.

Venkatesh Rao (@vgr), “It’s funny how people think a post-apocalyptic landscape will be relatively flat…” Twitter, October 5, 2019, ➝. While Rao holds a PhD in Aerospace Engineering and previously was a researcher at Xerox and Cornell, he currently works independently as a management consultant and writer, sharing analysis via his popular blog Ribbonfarm and Twitter. While not a well-known theorist like Latour, Rao is one of a growing number of critical thinkers exploring the present in interesting ways outside the limits of traditional institutions. In this vein, see New Models, ➝.

Manuel Castells, The Rise of the Network Society, The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture Vol. I (Malden and Oxford: Blackwell, 2009).

Thomas Barnett, The Pentagon’s New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-First Century (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2004), 8.

Ibid., 8.

See Stephanie Wakefield, “Urban resilience as critique: Problematizing infrastructure in post-Sandy New York City,” Political Geography 79 (2020); Kate Driscoll Derickson, “Urban Geography III: Anthropocene Urbanism,” Progress in Human Geography 42, no. 3 (2018): 425–435; Ross Exo Adams, “Becoming-Infrastructural,” e-flux architecture, 2017, ➝.

See Carl Folke, “Resilience,” Ecology and Society 21, no. 4 (2016): 44; Kevin Grove, Resilience (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018).

Bruce Braun, “A New Urban Dispositif? Governing Life in an Age of Climate Change,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32, no. 1 (2014): 49–64.

Nils Gilman, “The Twilight of Social Modernism,” in Plutocratic Insurgency Reader, eds. Robert Bunker and Pamela Ligouri Bunker (Bethesda: Small Wars Foundation, 2019), xix.

Mike Davis, City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (London: Verso, 1990).

Nils Gilman, “Plutocratic Insurgency,” in Plutocratic Insurgency Reader, eds. Robert Bunker and Pamela Ligouri Bunker (Bethesda: Small Wars Foundation, 2019), 2.

Ibid., 2.

Rory Rowan, “Beyond Colonial Futurism: Portugal’s Atlantic Spaceport and the Neoliberalization of Outer Space,” e-flux lectures, April 18, 2018, ➝.

This orientation is found in Naomi Klein’s response to the popularity of Musk’s shooting a car into space in 2018; Naomi Klein (@naomiaklein), “About Elon’s big day…this is a car commercial in space. Everyone: pls stop participating,” Twitter, February 7, 2018, ➝.

Steven Erikson, Willful Child (New York: Tor, 2014).

“Going to Space to Benefit Earth (Full Event Replay),” Blue Origin, May 9, 2019, ➝.

Fred Scharmen, Space Settlement (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019). See also Felicity D. Scott, “Securing Adjustable Climate,” in Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary, eds. James Graham, et al. (New York: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2016): 90–105.

Marina Koren, “Jeff Bezos Has Plans to Extract the Moon’s Water,” The Atlantic, May 10, 2019, ➝.

Ibid.

Michael Bang Petersen, Mathias Osmundsen, and Kevin Arceneaux, “A ‘Need for Chaos’ and the Sharing of Hostile Political Rumors in Advanced Democracies,” PsyArXiv, September 1, 2018, ➝. The authors conducted four surveys in the United States (5,157 participants), and two in Denmark (1,336 participants). Media stories on the survey framed the affirmative responses as a window into the hearts and minds of right-wing Americans; however, according to one of the authors, affirmative responses “correlate positively with sympathy for Trump but also—although less strongly—with sympathy for Sanders. It correlates negatively with sympathy for Hillary Clinton.” See Thomas Edsall, “The Trump Voters Whose ‘Need for Chaos’ Obliterates Everything Else,” New York Times, September 4, 2019, ➝.

Chloe Watlington, “Who Owns Tomorrow?” Commune 5 (Winter 2020), ➝; see also Phil Neel, Hinterlands: America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict (London: Reaktion Books, 2018).

Neel, Hinterlands, 131–146.

Alfredo Bonanno, From Riot to Insurrection: Analysis for an anarchist perspective against post-industrial capitalism (London: Elephant Editions, 1988).

Eva Haifa Giraud, What Comes After Entanglement? (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019).

Wakefield, in press.

Annalee Newitz, “How to be a smart Coronavirus prepper,” New York Times, February 29, 2020, ➝.

Peter Sloterdijk, Bubbles: Spheres I (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2011).

See Elizabeth Grosz, Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 69; Kathryn Yusoff, et al., “Geopower: a panel on Elizabeth Grosz’s Chaos, territory, art: Deleuze and the framing of the earth,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30 (2012): 971– 988; Philip Steinberg and Kimberley Peters, “Wet ontologies, fluid spaces: giving depth to volume through oceanic thinking,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 33 (2015): 247–264; Stuart Elden, “Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power,” Political Geography 34 (2013): 35–51.

See John Law, “What’s wrong with a one world world?” Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory 16, no. 1 (2015): 126–139; Stephanie Wakefield, “Inhabiting the Anthropocene Back Loop,” Resilience: International Policies, Practices and Discourses 6, no. 1 (2018): 1–18.

See Clive Barnett, The Priority of Injustice: Locating Democracy in Critical Theory (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2017); Stephen Collier, “Topologies of power: Foucault’s analysis of political government beyond ‘governmentality,’” Theory, Culture & Society 26, no. 6 (2009): 78–108.

Chandler, Ontopolitics in the Anthropocene, xvi.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

.png,1600)