The globe is on our computers. No one lives there.

—Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak1Being human is a praxis.

—Sylvia Wynter2

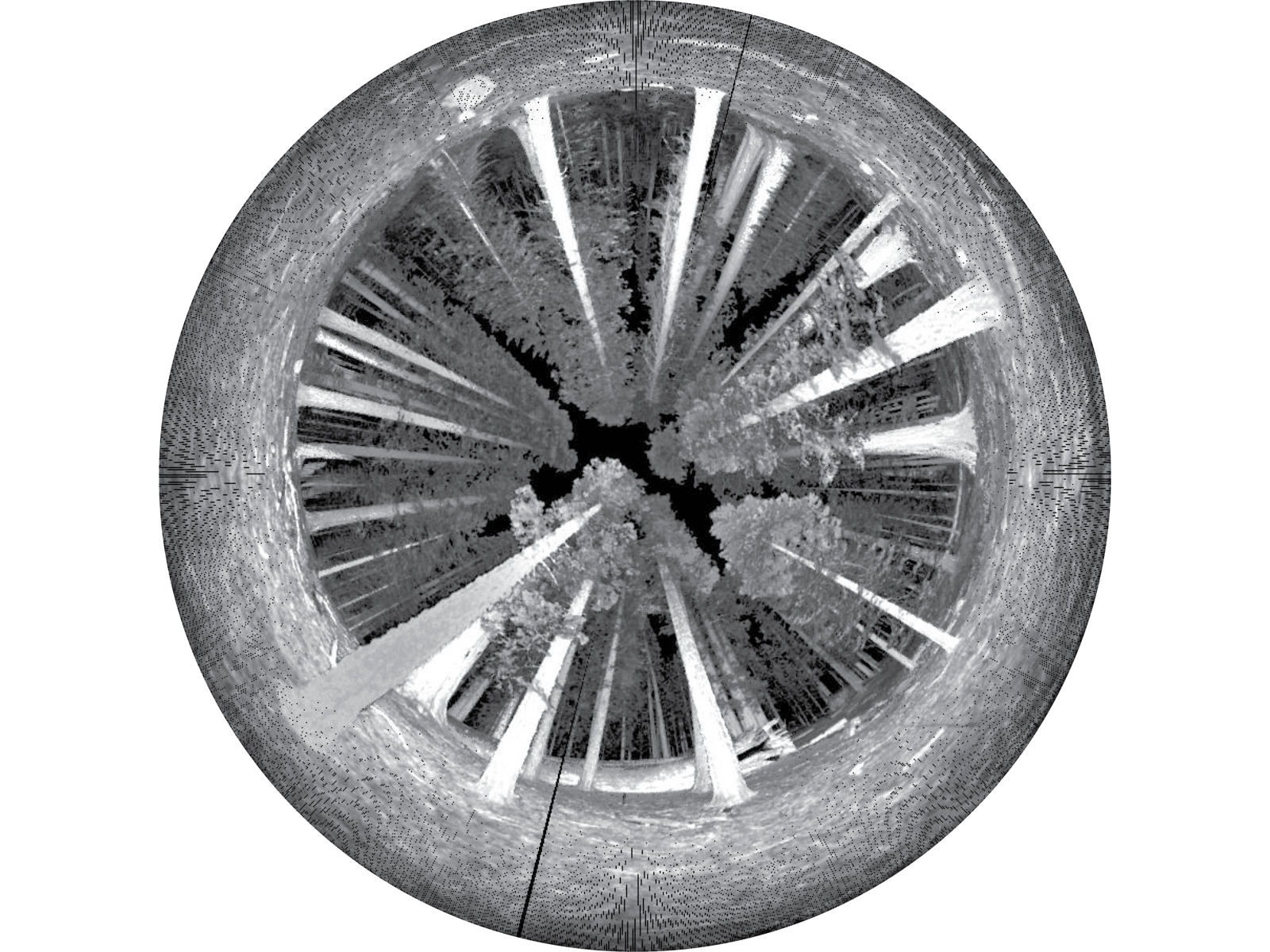

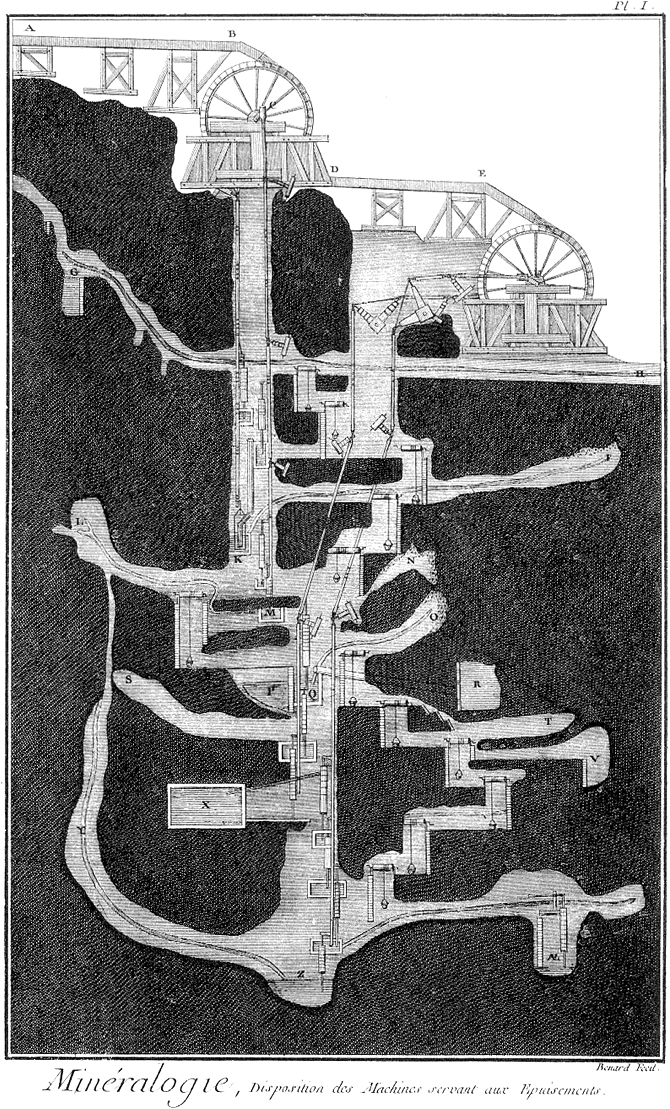

Multiple images stare out from between the lines of this text. They tell planetary stories. They are also forest stories. Through remote sensing, one image captures the accelerating decline and loss of forests in the Amazon. This time-lapse image produced by NASA begins in 2000 with an intact patch of forest green in Rondônia, Brazil. Over the course of twelve years, roads and settlements encroach upon and fragment the forest into corridors and swathes of brown terrain. By 2012, this same forest section had been turned into a pockmarked landscape, the work of extraction evident through the steady consumption of forest-as-resource.3 Another image switches from remote sensing to LIDAR scanning of the Black Forest in Germany. Forests are being lost, as the remote-sensing images indicate, yet they are also changing in structure and, in some cases, with ongoing resource and capital accumulation, losing their ability to store carbon.4 Yet another image shifts from these monitoring-based documents of forest decline to protestors occupying tree canopies in an attempt to halt their decline and destruction. Cables and wires secure figures in mid-air, attached to trunks, suspended in the thick of trees and impending logging activity. A final image moves from mass resistors protesting the construction of the Newbury Bypass in the UK to Palawan tribes harvesting honey from hives in Ginuqu trees in the Philippines, where for over a decade mining activity has threatened forests and forest-based ways of life. Here are forest people, subjects made with and through forest practices. Each of these images suggests ways in which to figure and reconfigure human-planetary relations.

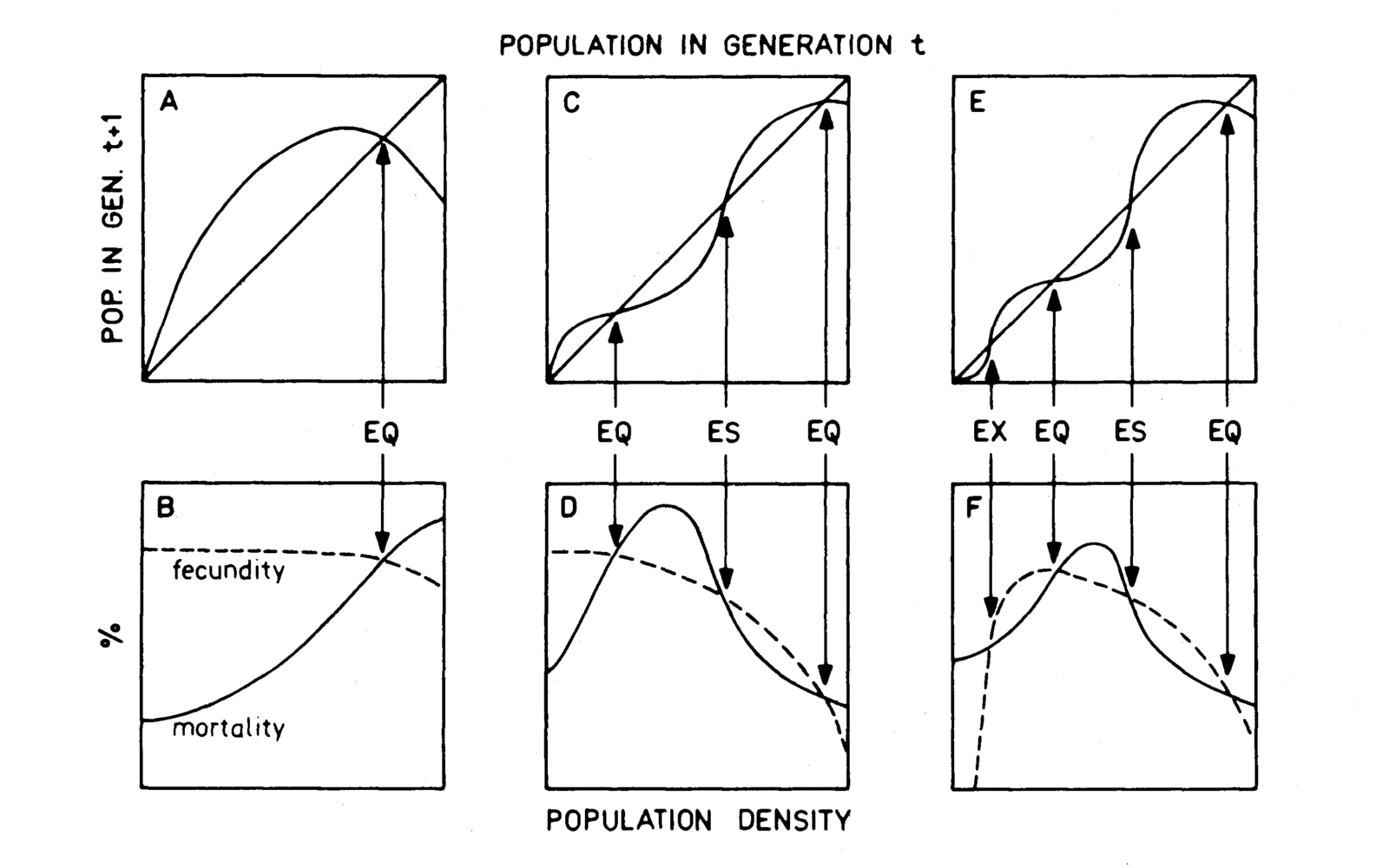

The forest, carbon, and media imaginaries that are captured in these different images tell diverse stories that span the remote, the durational, the extractive, the accumulative, the inhabited, and the contested. Forest media differently signal the configuration of the planetary and planetary subjects. Images such as these are increasingly common, charting the loss of forests as carbon sinks, the accumulation of heat leading to climate change, and the human subjects who are variously constituted along with these shifting environments. The planet transitions from forest to development, and remote and ubiquitous sensing technologies monitor, log, and display these changing conditions, as humans enter the frame as a diverse array of Earthlings, from remote scientists to protestors or pre-capitalist figures. With over four billion hectares of forest worldwide, these forests and their inhabitants are increasingly captured through monitoring and sensing media that seemingly provide a more planetary understanding of forests as systems. Yet these images also lead one to ask: In what ways does the planetary become evident—whether as object, process, or event? How is the planetary configured, rather than assumed and given? Is it only at the most zoomed-out scale of remote sensing, or through the LIDAR scanning of forests? Is the planetary evident in the temporal processes that endure over time and register through the composition of a forest, or through the occupation of a forest canopy or treetop?

It is now not uncommon for the planetary to be invoked in discussions of technology. Technology—especially computational technology—is analyzed as something on the “scale” of the planetary. Technology is seen to overrun and command the planetary. The planetary is discussed as a figure of massiveness. Its invocation suggests total dominion: the rolling out of behemoth systems that hold the planet and all of its entities in a space of complete capture. This total view of Earth has an even longer history within modes of control and colonialism. As Elizabeth DeLoughrey writes, “modern ways of imagining the earth as a totality, including those spaces claimed for militarism and globalization, derive from colonial histories of spatial enclosure.”5 While the total view might, on the one hand, suggest a mode of globality aligned with coloniality, on the other, it also suggests a mode of technology that is similarly aligned with colonial projects. The detached and distant view of Earth produces an entity that could seemingly be managed—or programmed. This total view of the planet suggests complete interconnectedness, but also forms of imperial control. It is the product of globality as well as universal science. A total view can even seem to be necessary: as a way to organize the problem of climate change, for instance, in order to act upon it. Climate change is an event that comes into view through planetary computation, where global infrastructures make it knowable.6 Yet in what ways do these modalities of the planetary reduce the possibilities of what the planetary is or might become—of being planetary as praxis? How might it be possible not to remake the pretensions of globality and globalization through planetary media projects, but rather begin to unsettle figures of totality and regulation in order to attend to the incommensurate, the unjust, and the yet to be recognized?

These questions point toward other readings of the planetary and of praxis informed by the works of theorists Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak and Sylvia Wynter. In asking what other figures or modalities of the planetary might be operationalized beyond those of the planetary-scale, we can take the lead from the multiple deliberations on the planetary developed by Spivak, who in working with and re-constellating this term sought to open the planetary toward other (collective) inhabitations.7 In a different, yet resonant way, Wynter’s work indicates how the problem of the raced human is inextricably tied to planetary problems. The “catastrophe” of climate change is also a “catastrophe” of the ways in which the “genre” of the human has been designated as an excluding and accumulating subject. Yet this mode or way of being human, as one limited genre, might also be questioned and transformed. She suggests a project that attends to being human as praxis as a way to engage with the processes that sustain—and that might also remake—ways of being human.8

Reading across these concepts of the planetary along with ideas for transformed and praxis-based approaches to the genres of being human, these thinkers and practitioners present other ways of encountering planetary problems by rethinking planetary subjects and humans that attempt to undo present catastrophic modes of accumulation. The question of the planetary cannot be addressed without also reworking divisions of the human, and the injustices that result from these limited modes of being. At the same time, by attending to the planetary it is possible to consider how the prevailing genre of the human has excluded more-than-human entities and relations. This proposal for a project of being planetary as praxis suggests that it might be possible to rework the usual approaches to humans and environments, as well as invent new conditions for planetary media.

The forest images included here are then less representational and more operational.9 Neither a worm’s-eye view nor a bird’s-eye view, they ask that one begin from within the thick of planetary inhabitations, in the forests as they are lost and potentially remade, and as they reconfigure relations across people, more-than-humans, technologies, politics, and the planetary. How does this gaze from within planetary inhabitations generate multiple modes of praxis? The ways in which climate change registers in forests can be read at once as a medial event, a planetary event, as well as an event implicating humans (of multiple designations). Forests are planetary media that register and operationalize collective accumulations of carbon and heat: they are proxies that record and register the effects of climate change.10 At the same time, forests involve multiple inhabitations, protests, and struggles for ways of being in the world. These images, as well as forests, are both forms of planetary media. They indicate ways of being planetary as praxis.

Being Planetary as Praxis

“The globe is on our computers.” In this statement Spivak suggests that the globe is contained by our exchanges, representations, and computations of it. The planetary can be a different figure for undoing the totality of globes and globality. Rather than bringing the Earth into view as a total object, as is often discussed through the figure of Earthrise, the planetary remains that which cannot be fixed or settled. The planetary resists representation. In Spivak’s development of the concept of the planetary, the point is not to generate an evasive figure, but rather to thwart an engagement with the planetary that hinges on uniform epistemic representations. The planetary is not a ground or grounding. Instead, it signals toward an “inexhaustible diversity of epistemes.”11 The planetary demands a mode of inhabiting with what escapes translation or “acceptance.”12 It does not definitively come into being as globes or picture-postcards of floating blue marbles.13 The planetary is the difference, distance, and duration with, within, and against which it might be possible to think differently about being human and becoming collective. The planet might even “overwrite the globe” to undo the assumed uniformity of global systems and exchanges. What planet is this? And what happens to computers when the globe inside is overwritten by the planetary, which computers cannot contain?

The planetary is a concept Spivak has worked and reworked, with her initial discussion of the planetary presented as a lecture on migration in Switzerland in 1997 as Imperatives to Re-Imagine the Planet. She expanded and developed her notions of the planetary and planetarity in numerous contexts, including her Death of the Discipline study of comparative literature written in 2003, where she takes a more psychoanalytic approach to the notion of planetarity.14 She subsequently extends this concept in multiple places, including in a planetarity contribution to the Welt (or World) entry in the Dictionary of Untranslatables.15 This is a concept that Spivak has written and rewritten, forged and revised. It is in her earlier 1997 discussion though that she draws attention to the planetary as a way of figuring the subject and “collective responsibility.”16

The imperative that Spivak sets out in her 1997 text is one of re-imagining the planet. This re-imagining might be read as a speculative condition that encounters the planetary beyond the abstractions of the globe and globalism. It also refigures what humans are through considering how subjects form through conditions and even rights to collective responsibility. Spivak’s articulation of this concept was formed specifically within the context of considering how to “think the migrant” in Switzerland, when immigration was occurring from beyond Europe.17 The planetary in this sense is not proposed as an abstract figure of earth science, nor is it a unifying globe that would make uniform and universal conditions for all humans. Instead, the planetary is in many ways irresolvable, and yet it is a way to figure, de-figure, and re-figure collective responsibility to the other in postcolonial and decolonial circumstances.18

Terrestrial Laser Scanning of a “Plenterwald” Forest in Southwest Germany, 2014. Source: Landconsult.de.

The planetary at once reworks designations of the migrant beyond the nation-state, but also gives rise to a set of considerations for how a “practical dialogics” might keep in play multiple modes of human inhabitation without having to resolve or synthesize these, or to render them within a relation of domination or subjugation.19 This is another way of parsing subjects and communities through reference to the planetary. With this in mind, Spivak proposes: “Let me then modify my title: I speak of an imperative to re-imagine the subject as planetary.”20 By re-imagining the planetary, the subject is also re-imagined. In other words, the designations of planet have consequences for the designations of subjects and communities. Far from a total force, absolute ground, or artifact of natural science, the planetary is more of an indeterminate condition and set of relations that sparks new encounters with collective inhabitations that do not turn into “multicultural liberalism,” or into the usual designations of environmentalism. Both the universal subject and the globe are undone in this planetary proposal.

This re-imagining of the subject is taken up in a different yet resonant register in the work of Wynter. For Wynter, the human as a category is formed through exclusions, especially on the basis of race. Wynter’s approach involves finding ways to do the human otherwise. Her work is an erudite reworking of the human toward other genres of being human, not as a definitional practice, but as a mode of praxis. This praxis has consequences for potentially undoing how people are raced, classed, sexed, and subjugated to be outside of the universal category of the human. “Being human as praxis” is thus Wynter’s proposal for how to expand the genres of the human to take account of and transform the racial and economic injustices and exclusions that are propagated through the current genre of the human. This praxis also experiments with other ways of being human in order to pluralize and diversify possibilities for being human—and by extension—for being planetary. Indeed, this is the point at which the planetary might be mobilized as praxis.21

By putting Spivak into dialogue with Wynter, it is possible to recast both the figure of the planetary, and the “genre of the human,” as Wynter has termed it. Planetary life and the figure(s) of the human are intimately connected. Indeed, as Wynter has convincingly demonstrated, the current version of the human that dominates modern life is not only based on a white Western privileged subject that is racially excluding; it also is an accumulative mode of the human as homo economicus.22 What has been rationalized and naturalized is a reductive figure of the human that is based on ongoing accumulation. Those people who do not figure as accumulators do not fit within the prevailing genre of the human. Indeed, those others who are outside the category of human might be extracted from, subjugated, dispossessed, or exploited in order to enable the accumulation of categorical humans. Furthermore, this mode of the human-as-accumulator leads to multiple exclusions and reductions in the possibilities for other ways of being human. Homo economicus—human as accumulator—is a figure of planetary destruction, since the crisis of climate change can on one level be characterized as a crisis of accumulation—not just of carbon and heat in the atmosphere and biosphere, but also as an accumulative mode of the human that is forever consuming and bound to economic growth. The split and designation of this particular category of human is then not just a matter of racial and social justice—how these humans are designated, and who does and does not belong to the Western bourgeois delineation of the human—but also it is a matter of planetary survival. The genre of the human must be expanded so that other less destructive modes of being human—and being planetary—might be formed.23

Wynter’s discussion indicates how we might find ways to do the planetary otherwise. If the subject or human were here to become planetary, following Spivak read along with Wynter, the universal designations of human and planet would be re-made and re-imagined. If Wynter proposes being human as praxis as a way to rework the possibilities for opening the category of the human, being planetary as praxis is a way to engage with the planetary-human joins that might also be re-imagined.24 We are planetary creatures, Spivak suggests, but this is not a fixed designation, as Wynter’s work further indicates. The sutures of difference that run through and across planetary creatures are also potential lines of praxis, giving rise to alternative configurations of “planetary thought” and planetary being and becoming.

The split into a particular category of human also involves, as Marisol de la Cadena suggests, a partitioning into universal nature and universal humans that depends on keeping these categories separate. Partitioning is not just a way of designating the planetary and the human. It is also a way of operating on the relations and segregations of each, such that ways of turning “nature” into “resource” and humans into accumulators might also occur. De la Cadena tells these stories through people’s struggles to resist development, to struggle against the conversion of their relations with more-than-human entities into “resources.” And yet, as she writes, “The interruption of the universal partition is a political and conceptual worlding event; what emerges through it is not a ‘mix’ of nature and human. Being composed as humans with nature—if we maintain these categories of being—makes each more. Entities emerge as materially specific to (and with!) the relation that inherently connects them.”25 De la Cadena reminds that the categorization of the human is not just one of making sub-humans; it is also one of carving off other more-than-human entities into categories such as resources. Writing across Wynter, Spivak and de la Cadena, one could say that separating humans by race, and designating the planetary as a globe or more-than-humans as resources, also involves separating humans from worlds that spark them into (other) ways of being. Being planetary as praxis, in this way, involves working from within the forests; thinking through and working toward modes of being neither from a ground or grounding, nor from above in a position of mastery or partitioning, but from within the middle of asymmetrical yet non-subjugating planetary relations.

In the current context, this might also mean that characterizations of the problem of climate change could be recast. At the time of Spivak’s writing, the planetary was a way to address the question of migration within Europe as one of collectively responsibility. This question still continues, and is now combined with forced migration through climate change. In a not dissimilar way, climate change then raises related questions about what collective responsibility as right, and about what mode of being planetary as praxis, might emerge here. The work of these thinkers signals toward ways not just of expanding and remaking the genres of the human, but also to ways of reworking and transforming human-planetary relations. The forest is a crucial figure and space within which these relations could be rethought, since it at once resists a universal and singular view, while also bringing into focus a multiplicity of subjects and inhabitations. Parsing the human is also a practice of parsing the planet and planetary relations. Projects of addressing racial injustice and inequity might then also be ones that remake planetary inhabitations, and vice versa. This could “unsettle” colonial ways of being as part of the operation of working toward less destructive inhabitations.26 How might this approach to the planetary and to being planetary as praxis then inform the ways in which that “unparalleled catastrophe for our species,” the event of climate change, is addressed?

A Palawan climbing an aerial bridge made of rattan canes to reach a ginuqu tree canopy. Photo: Dario Novellino.

Hothouse Earth, Hothouse Planetarity

In the summer of 2018, heat waves have occurred in multiple locations, from the High Arctic to southern Spain. Temperatures reached 46° Celsius in Portugal, and wildfires tore through Attica in Greece and northern Sweden. One scientific study published during this time suggested that the planet might become “Hothouse Earth,” with rising carbon emissions and temperatures forcing the crossing of thresholds to trigger non-linear responses and feedbacks so that methane begins to release from permafrost, forests cease to be carbon sinks and instead begin to be a net source of carbon, and oceans begin to acidify while absorbing less carbon and contributing humidity to atmospheres and energy to storms.27 Rather than operating in a relatively “stable” way with “self-reinforcing feedbacks,” ecosystems could amplify warming and irrevocably transform ecosystems—even to conditions that are inhospitable to human life—and in the process rapidly accelerate the process of climate change. Although the story of climate forcings, thresholds, and tipping points is not especially new, the article served as a reminder, in the midst of sweltering temperatures, forest fires, and flash floods, that planetary warming might kick into overdrive, making any current or near-future attempts at lowering emissions by marginal amounts an insufficient exercise.

While much of the focus within news media reporting on this article centered on the figure of the “Hothouse Earth” and its alarming rendering of a combusting planet, a less-reported aspect of the article pertains to the authors’ suggestion for ways to combat the scenario of a runaway warming planet. In order to prevent the possibility of “irreversible” climate change “driven by intrinsic biogeophysical feedbacks,” the authors suggest a pathway that could lead to a “Stabilized Earth” that could be achieved through “human-created feedbacks to a quasi-stable, human-maintained basin of attraction.”28 The authors suggest that “stewardship of the entire Earth System” would need to be addressed, including of the “biosphere, climate, and societies.” Examples of these Earth-sized actions that might move along to a stabilized state include not just using less fossil-fuel intensive modes of energy, but also developing new technologies, governance, and social codes. At the same time, planetary sinks might be cultivated to better store carbon. Forests here become a project for human stewards. Geo-engineering is also part of the mix, where “solar radiation management” could constitute part of the “stewardship” set of practices.29 Hothouse Earth thus becomes a medial project: it makes the planet into a medium of stabilized operation and control.

Robot sensor scanning tree canopies in the James Research Ecological Study Area, 2008. Photo: Jennifer Gabrys.

The planet, as the earth sciences often remind, consists of interconnected yet unpredictable systems. Planetary forces might easily cross a threshold toward other less livable conditions. This is not the self-correcting planet put forward in Gaia theory, but rather is one where accumulation runs amok. Carbon and heat do not just accumulate; they also amplify changes to the climate that differently shape conditions of planetary distress. Yet the planetary is ideally projected to be a figure of stability and control. The curious “basin of attraction” that humans might cultivate raises numerous questions about how “Hothouse Earth” might be addressed. What humans, or genres of being human, as Wynter would term it, are these? Specific practices of “stewardship” proposed potentially include technocrats involved in geo-engineering, forest workers reforesting continents, as well as speculative figures yet to be created for their planetary maintenance skills. It is equally unclear what sort of planet this might be, which would yield to a process of stabilization, veering away from “Hothouse Earth” to “Stabilized Earth” through the guiding practices of humans. Indeed, the end of “human civilization” is one aspect of climate change that scientists often designate as a likely outcome in their scenarios. Yet what does the planet have to become such that human civilization in this rendering might be sustained, however problematic that civilization might be? And what other planet-human configurations might be proposed such that human “civilization” is not a project of stabilizing the planet, but rather of re-imagining the human and the planetary as praxis?

“Hothouse Earth” then gives way to a “Hothouse Planetarity.” The usual forms of environmental science and environmentalism turn up here as conducted through the categories of universal science and the universal human-as-steward. Yet as Spivak writes, “to talk planet-talk by way of an unexamined environmentalism, referring to an undivided ‘natural’ space rather than a differentiated political space, can work in the interest of this globalization in the mode of the abstract as such.”30 The globe that is on our computers—and in a basin of attraction—is one that can seemingly be controlled by universal humans. Even if the “natural space” of climate science is one largely impacted by anthropogenic activities, here the proposal for how to address “Hothouse Earth” does not differentiate how such stewardship activities would unfold across diverse locations and by multiple contributors. For instance, humans are much more likely to become climate migrants in the Global South, and potentially less able to contribute to forest stewardship or geo-engineering projects, for better or worse.31 Indeed, science here remains within a universal and even “silent” modality, as Wynter would term it, by not engaging with the cultural practices and stories that code and recode ways of being human.32 Yet the problem of climate change forces a reconsideration of how new subjects, new humans, and new planetary relations are irrupting, even within proposals by climate scientists. “Hothouse Earth” proposes that a legion of eco-stewards emerge who would continually look after the planet to keep it in a stable state. Yet “Hothouse Planetarity” asks questions about which humans—and which genres of the human and the planetary—are enrolled here. Questions of social justice cannot be separated from problems of deforestation, biodiversity loss, rising temperatures, and environmental pollution. Planetary inhabitations are entangled with ways of being planetary as praxis.

To know the planet can be a way to fix it as a figure of analysis and management. Stability could even be seen to be a way to rid the planet of alterity: to make it knowable and so manageable within a universal science. It can be a way to elide planetary differences both within and throughout terrestrial inhabitations. Indeed, as the overall Welt entry to the Dictionary of Untranslatables charts, to know the world (here a different but useful concept to call into play when discussing the planetary) can be a much different relation than to have world.33 This having of world is less a condition of possession, and more a mode of experience and engagement. Where we are in the world and the world is in us, as Whitehead would term it.34 The planetary involves remaking environmental relations and remaking the subject-superject. If the planetary is a site of difference, it also constitutes and runs through subjects in diverse ways. If Spivak’s consideration of the planetary and planetarity is brought to bear, where the usual forms of environmentalism and custodianship are suspended, and yet the right to (collective) responsibility is held in play, then how might a “Hothouse Planetarity” unfold as a necessary rejoinder to the figure of the “Hothouse Earth”?

Planetary Media: Out of the Planetarium

This immense wooing of the cosmos was enacted for the first time on a planetary scale, that is, in the spirit of technology.

—Walter Benjamin35

While Benjamin wrote “To the Planetarium” as a way to capture the wartime effects of planetary-scale technology, becoming planetary and being planetary as praxis would suggest a move “out of the planetarium” as a way to disassemble the universal figurations of the planetary scale and universal science. By moving out of the planetarium of the total Earth and planetary-scale talk, one might also venture into the forest to find oneself in the thick of a set of planetary relations that are not easily fixed or figured, but which in their incommensurability signal toward other ways of being planetary as praxis. Being planetary as praxis is a move out of the planetarium to consider other designations and mobilizations of the planetary, the human, and techno-cultural practices. In this sense, media are neither planetary in scale, nor should they be figured through a universal computational or earth science imaginary. Instead, the planetary should be unsettled, along with media and the human. However, this unsettling does not arrive at an elemental materialism at the core of media, and it does not suggest a command-and-control stratum of technology permeating the globe. Instead, the planetary is an ongoing process of creating, articulating, and transforming human subjects and collective inhabitations.

The globe is on our computers, but the planetary forces a diverse and sprawling set of encounters with media, technology and science that might remake these practices. The becoming planetary of media is a concept that addresses the ways in which the planet, Earth, and environments are figured as medial projects.36 The planetary within discussions of media and technology has at times taken on an elemental or epic quality. In a not dissimilar way, environmental science often casts the planet as mix of large-scale atmospheric, oceanic, terrestrial, and biotic systems and media as elemental records. And yet, planetary media might necessarily involve an unsettling of these categorizations of the planet or media, since planetary media would neither be universally designated nor abstractly partitioned. To refer to planetary media is to call attention to the differences that planetarity invokes, to the inassimilable and incommensurate conditions of planetary inhabitation that cannot and do not settle into one coherent or planar object: not the Earth of earth sciences, the globe of capitalism, or the human of homo economicus. The becoming planetary of media forces a recasting of the usual ways in which the planetary and media might be understood or approached. In this space the becoming planetary of media might unfold not so much as a tale of elemental media, but rather more as collective narratives that generate lived storylines toward more just worlds for diverse humans, more-than-humans, and their planetary inhabitations.

Being planetary as praxis and the becoming planetary of media thus asks how the planetary might provoke other ways of figuring planetary inhabitations—of moving out of the planetarium and into the forest. Being planetary as praxis involves an attention to questions of colonial imaginations and control, of racial and economic exclusions, of environmental injustices, and of universal science and global abstractions that might be de-figured, superseded, and transformed in the search for more open and just ways of being human and planetary that are still to be re-imagined. The planetary is necessarily transfigured when re-considered beyond the partitions of universal science and global capitalism. The ways in which the planetary is constituted, informed, and even de-figured have consequences for planetary crises such as climate change, as well as proposals for addressing these crises through projects such as cultivating forests as carbon sinks. This approach to the planetary involves not just an abstract or totalizing set of planetary forces, but rather involves very distinct and unequal ways in which planetary politics, relations, and technicities unfold. This transfiguration reworks the planetary away from abstract globes and toward different genres of humans and collective responsibility. Planetary media in this context are less categories of elements and resources and more a constitution and re-constellation of collective responsibility through a planetary imperative. At the same time, it is not a human designation of the planet, but rather an unsettling of the ways in which subjects are partitioned and formed, against universal and colonial figurations.

This approach moves away from the satellite view or the much-referenced images of Earthrise or Blue Marble and toward the more entangled environs of a forest. While this view does not offer up an absolute expanse, fixed figure, or even foundational elementalism as the basis for knowledge, it does remake planetary-subject relations. Forests become planetary media. They are proxies for climate change—they tell stories about the accumulation of carbon and the shifts in environmental conditions. At the same time, diverse forest inhabitations also offer another way of figuring the human-planetary genres and praxes that move away from globes, universal man, accumulators or subjugators, to engage with the practices that irrupt through the prospect of becoming planetary and being planetary as praxis. More-than-human contributors, other genres of the human, and multiple worlds and ways of being members of collectives come into view here.37 Other ways of thinking about forest work—in contrast to the “Hothouse Earth” scenario—also emerge here. Mapping and monitoring with remote sensing platforms, forest watch toolkits, and sensing technologies are one way to figure modes of engagement with forests. Yet from within this reworking of the planetary and the human, there are still many other pre- or post-accumulative modalities, media and storylines that might be recognized and created. Becoming planetary is a way to consider how the planetary is not a uniform or fixed set of conditions, but rather signals conditions of difference, as well as collective responsibility and possibility with and through those differences.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Imperatives to Re-Imagine the Planet (Vienna: Passagen Verlag, 1999), 44.

Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species?” in Katherine McKittrick ed., Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015), 23.

NASA Earth Observatory, “World of Change: Amazon Deforestation,” ➝.

Elizabeth Zubritsky, “New NASA Probe Will Study Earth’s Forests in 3D,” NASA Global Climate Change, ➝.

Elizabeth DeLoughrey, “Satellite Planetarity and the Ends of the Earth,” Public Culture 26, no. 2 (2014), 261.

Paul N. Edwards, A Vast Machine: Computer Models, Climate Data, and the Politics of Global Warming (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2010), 25.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Imperatives.

McKittrick, Sylvia Wynter.

Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” Public 29 (2004): 12–22.

Jennifer Gabrys, “Sensing an Experimental Forest: Processing Environments and Distributing Relations,” Computational Culture 2 (2012), ➝.

Spivak, Imperatives, 74.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Planetarity” (Box 4) for “Welt,” in Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon, ed. Barbara Cassin (Princeton University Press, 2014).

For a discussion of the unsettling of these “global-world-spaces” within this collection on Accumulation, see Kathryn Yusoff, Epochal Aesthetics: Affectual Infrastructures of the Anthropocene,” in Accumulation, Nick Axel, Daniel A. Barber, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Anton Vidokle eds. (e-flux Architecture, 2017–2018), ➝.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “Planetarity,” in Death of a Discipline (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 71-102.

Spivak develops and reworks the planetary and planetarity in many more texts beyond these, and this is not an exhaustive list.

Spivak, Imperatives, 54.

Spivak, Imperatives, 44.

On these different renderings of science within Aboriginal land practices, see Helen Verran, “A Postcolonial Moment in Science Studies: Alternative Firing Regimes of Environmental Scientists and Aboriginal Landowners.” Social Studies of Science 32, nos. 5-6 (2002): 729–762.

Spivak, Imperatives, 80.

Spivak, Imperatives, 48.

The concept and phrase—being planetary as praxis—that I develop here is an extension on this phrase coined by Wynter, which she further elaborates in conversation with Katherine McKittrick in the stirring collection, Sylvia Wynter: On Being Human as Praxis. McKittrick, Sylvia Wynter.

Sylvia Wynter and Katherine McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species?” in McKittrick, Sylvia Wynter.

Wynter and McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe for Our Species?”

Wynter is influenced by Marx in her understanding of praxis, but also draws on Judith Butler in her discussion of praxis and gender, which she develops into an original take on storytelling, code, neural science and being human as praxis.

Marisol de la Cadena, “Uncommoning Nature,” e-flux Journal 65 (May–August 2015), 4.

Sylvia Wynter, “Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation—An Argument,” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (Fall 2003): 257–337.

Will Steffen, Johan Rockström, Katherine Richardson, Timothy M. Lenton, Carl Folke, Diana Liverman, Colin P. Summerhayes, Anthony D. Barnosky, Sarah E. Cornell, Michel Crucifix, Jonathan F. Donges, Ingo Fetzer, Steven J. Lade, Marten Scheffer, Ricarda Winkelmann, and Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene,” PNAS 115, no. 33 (August 14, 2018): 8252–8259.

Steffen et al., “Trajectories,” 8254.

Steffen et al., “Trajectories,” 8256.

Spivak, “Planetarity” (2003), 72.

Climate migration and its consequences for social and environmental justice is a topic addressed through numerous research articles and reports. For example, see Andrew Baldwin, “Racialisation and the Figure of the Climate Change Migrant,” Environment and Planning A 45, no. 6 (June 2013): 1474–1490. At the same time, this topic is the focus for security and development, as is evident through the report: Kanta Kumari Rigaud, Alex de Sherbinin, Bryan Jones, Jonas Bergmann, Viviane Clement, Kayly Ober, Jacob Schewe, Susana Adamo, Brent McCusker, Silke Heuser, and Amelia Midgley, Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration (World Bank, Washington, DC, 2018), ➝.

Wynter and McKittrick, “Unparalleled Catastrophe,” 17. Wynter draws here on Aimé Césaire, from “Poetry and Knowledge,” in Refusal of the Shadow: Surrealism and the Caribbean, Michael Richardson ed. (New York, Verso, 1996 {1946}), 134–146.

Pascal David, “Welt” in Dictionary of Untranslatables, 1217–1224.

Alfred North Whitehead, Modes of Thought (New York: The Free Press, 1966 {1938}). This planetary approach potentially runs up against Wynter’s configuration of the subject within autopoietic systems, where subjects construct environments—unless subjects are extended to multiple other entities. This discussion of autopoiesis and subject-superjects is a topic for another study.

Walter Benjamin, “To the Planetarium,” One-Way Street, Reflections, 93.

I have previously discussed the becoming environmental of computation to consider how sensor technologies configure and distribute environmental experiences. Through this discussion, I suggest this extended encounter with the planetary, the human, and praxis could stir a different constellation of the planetary aspects of media and technology, especially as configured in relation to climate change. Jennifer Gabrys, Program Earth: Environmental Sensing Technology and the Making of a Computational Planet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Towards an Anthropology beyond the Human (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013); Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “The Crystal Forest: Notes on the Ontology of Amazonian Spirits,” Inner Asia 9 (2007), 153–172.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

.png,1600)