A firestorm is a fire whose intensity is so great that it creates and sustains its own weather. Its own wind system, to be more precise. The Horse River Fire that devastated the town of Fort McMurray, Alberta in 2016, for instance, generated pyrocumulonimbus-driven lightning: fire-generated clouds that produced lightning which, in turn, ignited or reignited more fires. Altogether, Horse River burned 1.4 million acres. Firestorms used to be freaks of weather, but are becoming more common. The frequency of megafires, fires that burn at least 100,000 acres, also has increased. Climate change is one factor in the uptick—warmer, drier weather brings more fire, creating fuels (dry brush, lightning, etc.).1 But the commonness of megafire also has to do with the increased proportion of the landscape called intermix: environments where residential or industrial use spills into wildlands. “In the United States, there are now more than 46-million single family homes, several hundred thousand businesses, and 120 million people living and working in and around the country’s forests,” writes the Canadian journalist Edward Struzik.2 Despite national programs intended to build resilience into forest communities, like Canada’s FireSmart and FireWise in the US, “homes built within a stone’s throw of a forest continue to be built with highly combustible cedar-shake shingles and flanked with ornamental cedars.”3 I recall a photograph of burning cedar topiary in Ventura, California—my old hometown—amongst the news images of southern California’s Thomas Fire of December, 2017. The topiary, symmetrically framing the entryway to a hillside home, was lit by flame at the top, like candles. Our high-end real estate, edged against forests, tucked into hillsides, offers an accumulation of fuel.

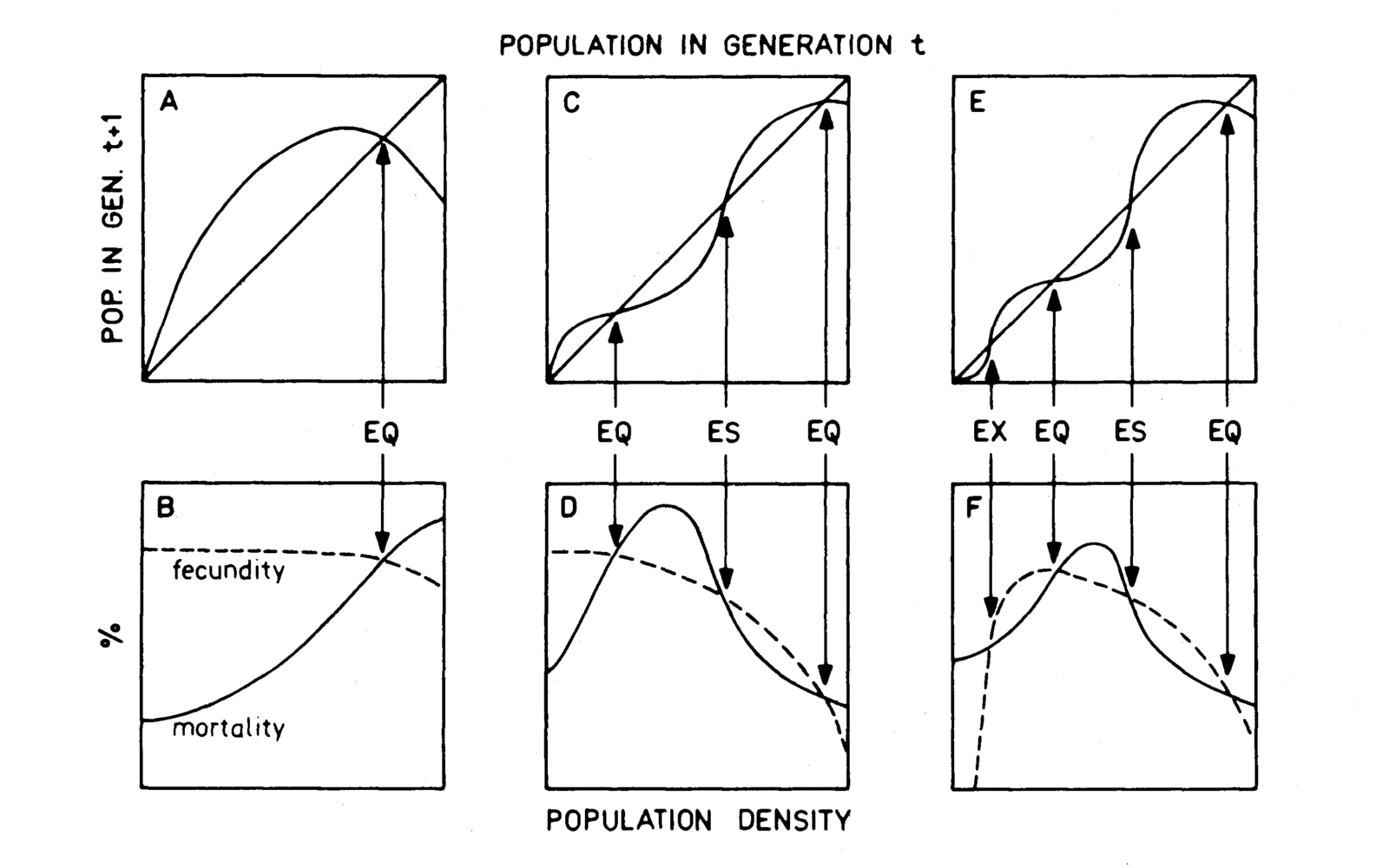

The scaling up of fire into pyrocumulous weather across North America has to do with a human failure to interact with fire in creating healthy ecosystems. This failure is attributable in part to the reimagination of fuel as carboniferous matter to be worked through internal combustion, an imaginative shift made during the industrial revolution. Cultural theorists Nigel Clark and Kathryn Yusoff argue that the cultural study of energy ought to be “combustion-centered” in the long human history of “artisanal pyrotechnologies” rather than fixated, as it has been, on the relatively short reign of internal combustion.4 The industrial revolution marks the beginning of a move away from fire as work humans do outdoors or in the relatively open space of the household hearth (the latter now conceived as a health hazard). “Fire is an extraordinarily interactive technology,” writes fire historian Stephen J. Pyne, “and humans can create powerful synergies by felling, ringbarking, grazing, sowing, pruning, digging, transplanting, moving species, and otherwise rearranging fuels and the patterns of fire.”5 The industrial revolution, the modern science of forestry, and the invention of public wildlands in the US and Canada curtailed both indigenous and settler-agricultural uses of fire. Both the scaling up of megafires into firestorms with their self-generated weather and the greater likelihood of megafires themselves are the products and the effects of colonization. The North American landscapes made by indigenous fire tenders and desired by settlers—who occupied the indigenous lands they admired and in some cases learned from or imitated indigenous fire tenders—are largely gone, at a time when only about 3% of US residents are farm workers.6 Modern agricultural landscapes are fossil fuelscapes, whereas wildlands, without the deliberate use of fire as an agent for thinning mature trees, become accumulations of fuel to spark massive, destroying fires.

“Academic forestry, betraying its agronomic origins, condemned fire as superstitious, slovenly, wasteful, primitive,” Pyne laments.7 Massive settling and road-building in the North American West of the late nineteenth century, including the creation of transcontinental railroads, opened up new fire corridors, landscapes of hasty construction and waste. The Gilded Age, Pyne tells us, was conceived by some elites—those with an eye toward European forest management—as “an environmental potlatch in which the frontier folk and the monopolist robber barons had gleefully heaped the nation’s natural wealth into flames.”8 This historical association of American decadence with fire ignored the pyrogenic character of many Western regions, like boreal forests, and many fire-friendly Western species. Pyrophytes are plants that have adapted to tolerate fire; pyrophiles are plants which require fire to complete their cycle of reproduction. The North American West has plenty of both, and there is significant scientific evidence that Western wildlife, too, benefits from fire—including increasingly scarce species like flammulated owls and spotted owls.9

The benefits of fire to animals arise from relatively low-intensity naturally occurring wildfires, not from the new breed of megafires attributable to the cessation of Native American and rural controlled burning, an irreplaceable means of resource management.10 As early as the start of the twentieth century California foresters recognized “Indian” intelligence on tending fire, and by the 1940s the science of fire prevention in the US recommended controlled burn, but fire suppression remains the primary work of federal agencies. And as sociologist Kari Norgaard has shown, the cultural violence done to Native communities by US policies of fire exclusion are at least as significant as the ecological and economic impacts of the same policies.11 Meanwhile, moribund twentieth-century infrastructures like above-ground power lines continue their tentacular reach into drier forests, recreating exurbanites drive their Range Rovers onto the Bureau of Land Management’s brush-lined gravel roads, private homes spring up on the edge of wildlands, and oil pads live within them.12 The very love of the wild instigated by North American environmentalism has generated an accumulation of tinder. Fossil fuel modernity made necessary, for some, the establishment and dream of wildlands. It now invades and privatizes wildlands, fanning the flames.

Insofar as fire fuel is a character of modern North American landscapes that signifies how they act as accumulations of tinder, it is also fire media. In other words, the dry brush, immature trees, pine needles, and other fuels of untended wildlands are expressive carriers of narrative and affect. Fire fuel tells a story of urban/settler ignorance of fire, and it is that story.

That said, fire generates deliberate media experiments, too. Modes of orientation toward fire reflect the complex of urban values that fire historians and fire ecologists point to as foundational to the settler/urban inability to recognize fire as an ecological tool. Historian Mike Davis has written extensively about the mediatization of Southern California as an apocalypse theme-park, noting how fire has been demonized as a kind of intruder into a Mediterranean climate that in fact depends upon fire for its health.13 My own experience as a southern Californian for fifteen years, and now as an Oregonian for five (in a region hit so hard by wildfire in late summer that I own a smoke-filtering mask) calls to mind a different kind of mediatization—fire-orienting media for the Anthropocene. The photographic, filmic, and cartographic media of megafires—especially abundant in online formats—describe relationships between the human subject and fires so overwhelming as to defy any knowledge we might have (even theoretically) of fire as a Neolithic or contemporary ecological tool. These media do not claim that humans and fire have been long-term collaborators in landscape design, nor that humans suppress fire in a triumph of Enlightenment modernity. Rather, they present the idea that fire is its own reality and, as with firestorms, its own weather, a mode of time (temps). If we consider time as an incredibly intimate media concept, insofar as it may express the experience of the human body and even species, what might it mean for “time” to be felt as explosive, multi-sited, and unpredictable—megafire time?14 What is being suggested here is the shifting temporality of Nature—another media concept that carries, for settler/colonialist cultures, the meanings and felt experiences of life. Natural time has become a kind of ambient trauma, dealing death to some and leaving survivors to tend the ruins or figure out how to get beyond the perimeter of the latest incident.

The graphic and data journalist Joe Fox created a virtual environment of megafire for the Los Angeles Times in January 2018, when the Thomas Fire was contained. Titled “The Thomas Fire: 40 Days of Devastation,” this interactive satellite map with a 3D terrain layer presents the fire through black narrative text boxes linked to specific satellite images. Lighter-colored instructional text boxes—like an author’s footnotes—hover in the midst of specific images. The viewer can “drag the map to look around” and flip an individual image on its axis to appreciate the 3D terrain layer. The narrative of the map progresses by way of the viewer clicking on a “next” tab, and is structured as a daily diary or incident report. Links in most narrative text boxes make possible a closer examination of a particular day’s progress.

Screenshot from Joe Fox, “The Thomas Fire: 40 Days of Devastation,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2018.

Screenshot from Joe Fox, “The Thomas Fire: 40 Days of Devastation,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2018.

Composite screenshot from Joe Fox, “The Thomas Fire: 40 Days of Devastation,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2018.

Screenshot from Joe Fox, “The Thomas Fire: 40 Days of Devastation,” Los Angeles Times, January 23, 2018.

The “God’s-eye view” made available by this map is both enlightening and it is infuriating. How can it be that a media tool as sophisticated as this co-exists with a culture so profoundly vulnerable? The sophistication of this media intelligence suggests a culture already having given up on Earth’s ecologies, honing its skills elsewhere. What is the relationship of the photographs showing moribund and poorly sited infrastructure—car-choked highways surrounded by flame, devastated suburban plats—to this gorgeous, interactive media? By the time Fox brings us to Day 38 (“281, 893 acres burned” and mudslides inundating the coastal town of Montecito), the narrative has developed an almost wry tone. “At least 100 homes were destroyed, and at least 21 people were killed, including some outside the mandatory evacuation zones.” Small red dots on the map image indicate where bodies were found among Montecito’s hillside homes. We see only two red dots in the mandatory evacuation zone, and the rest in the voluntary zone. As I count the red dots, I flip the map so that the mountains are vertical—almost a nervous preference for visual orientation to the human POV— and I search the hillsides for the area where I think an old friend of mine still lives, in a rented cabin. We used to ride horses up there together, winding around chaparral trails and stumbling into the grounds of elegant mansions. She’s a hermit, and I’m not sure she has a cellphone. I wonder if she, and her horse, are alive. Am I angry at this interactive media, almost a “game” version of tragedy? Not really. It has, after all, shown me how the fire moves. I am simply made uncomfortable by its visually arresting assurance, in juxtaposition to the chaotic, raw story it rationalizes. That incongruity reads a bit like a joke. (Maybe a rather old one, circa Chaplin’s Modern Times).

Day 40. The interactive map closes, suggesting I conduct my own exploration, outside of narrative time. In terms of memory, for those who lived through it or who know these places, the Thomas Fire has no narrative—an end, yes, but no therapeutic closure.

Online newspaper photographs—of charred avocado and orange trees at a market farm I used to visit in Santa Paula, the rural town near where the fire originated, and photographs of a charred mental health facility where a friend worked—vividly recall scenes of habitual living in and around Ventura in the early twenty-first century. I lived in a West Ventura neighborhood, near to the inland town of Ojai, for seven years. It was shocking to see my former everyday—with both the comfort and boredom that term implies—blackened and broken. In the first few days of the Thomas Fire in early December, I tried phoning my former next-door neighbors, but did not receive an answer. It was probably because they evacuated, but I have yet to reconnect with them. Another neighbor recounted the terror that she and others felt as the fire descended, the rapidity and absoluteness of its force—and this in an area where “hill fires” regularly occur. When the hill burned on its fairly regular, six-year cycle, neighborhood residents climbed onto their roofs with garden hoses. Southern Californians are used to suppressing—and even enjoying—their apocalypse theme-park. But the Thomas Fire scaled up far beyond creative, local response, resulting in the destruction of six hundred apartments and homes, twenty-three human deaths (two attributable to the fire, the rest to the mudslides), and the deaths of more than sixty-six horses.15 Its destruction was, and still is, traumatic. It was, briefly, the largest fire in California history, before being overtaken by the Mendocino Complex fire in 2018.

In the first five days of the Thomas Fire, no maps that I could find online made clear exactly where the burned houses were, exactly which neighborhoods were in the fire’s path and which escaped it. I learned more as I reached more friends by telephone. I know of no close acquaintances who lost property or life to the fire. My old neighborhood remains intact. For the seven years that I lived in that neighborhood, we fretted under the rolling landscape we called “the hill,” with its periodic fires and known risk for landslide—this landslide risk now a point of interest on Google Earth. We were a plucky neighborhood of Latinx, immigrants, and queers, considered both the bad part of town and the arts district. This time, neither the fires nor the slides got us. Aging electrical infrastructure still hangs precariously over the old neighborhood, with many of its houses from the 1920s still wired with knob-and-tube. California, like the rest of the West, gets hotter, drier. The landslide looms, waiting for the next El Niño.

Pyne, the fire historian, makes clear how ignorant suburban and urban people are of the rural uses of fire—and how this ignorance primes us to live in places and in habitats that accumulate fuel for megafires. While I largely agree with Pyne’s description of my demographic (I identify here as a settler/urbanite), I would quibble with his insistence that our primary means of conceiving fire is through the demonizing lens of mainstream environmentalism—which has turned fire into a weapon against Nature since the debut of the film Bambi in 1942.16 The source of my ignorance of fire can be located in another kind of media: InciWeb, a site well known to all US Westerners, and its analog predecessors.17 My relationship to fire has not been one of imagined antagonism, where I denigrate rural and indigenous fire tenders for torching the wilderness that makes my (sub)urban existence bearable. Yet the relationship I have to fire comes from a related strain of ecological and cultural blindness. My understanding of fire originates in a (sub)urban/settler image of wildlands, and much of the West, as sites of recreation. The way this relationship plays out is through driving. Driving to hike, to swim in a mountain lake, to kayak. Every time I drive east, toward Oregon’s high desert, for example, I check InciWeb for fire. Which roads you take, where you gas up, where you stay overnight, depends on where the fires are burning. It is not a matter of “if” they are burning. We assume fire, in late summer and early fall. Our task is to move around it. That pragmatic living with the fires of a desired elsewhere—in our diminishing and disrespected rural regions, in so-called wildlands—as if they are minor traffic frays to avoid, may be an even more potent imaginative block to building resilience to megafire than would be an explicit bias against fire.

Before you go anywhere, check InciWeb. Of the 85% contained “Boxcar Fire” in central Oregon, InciWeb recently told me: “The Deschutes and John Day Rivers, boat launch sites, camping areas and highways are open for recreation.” But: “Visitors should use caution while driving as rocks may dislodge and become a hazard along the roads. If precipitation occurs, flash flooding can move large amounts of soil and debris. Always be aware of potential hazards when moving through recently burned areas.”18 Why did so few residents of Montecito who were in the Thomas Fire voluntary evacuation zone choose to evacuate, such that twenty-one died? Fire’s relative normalcy in the West, for (sub)urban recreators, makes megafire and its corollaries, like mudslides, even more potent adversaries. The New West’s familiarity with wildfire is itself an accumulation of fuel. Fatal tinder.

See Tania Schoennagel, Jennifer K. Balch, et al. “Adapt to More Wildfire in Western North American Forests as Climate Changes,” PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) 114 (May 2, 2017): 4582–4590.

Edward Struzik, Firestorm: How Wildfire Will Shape Our Future (Washington DC: Island Press, 2017), 5.

Struzik, 15.

Nigel Clark and Kathryn Yusoff, “Combustion and Society: A Fire-Centered History of Energy Use,” Theory, Culture, and Society 31 (July 2014): 203–226.

Stephen J. Pyne. America’s Fires: Management of Wildlands and Forests (Durham, North Carolina: Forest History Society, 1997), 14.

This somewhat outdated figure is from Pyne, 1997.

Pyne, 16.

Pyne, 6.

Struzik, 223.

Struzik, 224.

See Kari Norgaard, “The Politics of Fire and the Social Impacts of Fire Exclusion on the Klamath,” Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 36 (2014): 77.

Mike Davis, “The Dialectic of Ordinary Disaster,” in The Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998), 9.

This is essentially Amitav Ghosh’s argument about the temporality of realism and/or Nature within the era of climate change. In Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 20-21. See also Davis.

Brittny Mejia, Harriet Ryan and Paul Sisson. “’An Unprecedented Loss of Life: The grim toll of Southland fires on animals born to run.” The Los Angeles Times, December 9, 2017, ➝.

Pyne, America’s Fires, 22.

➝.

“Boxcar Fire: Incident Overview,” National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), June 27, 2018, ➝.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

Category

Subject

The author thanks Heather Houser for explicitly identifying the genre of this map and for her innovative work on the “infowhelm” in the era of climate change.

.png,1600)