With the rise of Trumpism, the US finds itself in nothing less than a state of emergency. We face a conflictual and volatile regime of post-liberal plutocracy dedicated to extreme wealth accumulation, fueled by patriarchal and white supremacist resentment. With repressive attacks on independent media and civil society activism, the president’s administration appears poised to enhance militarized borders and surveillance-equipped counter-insurgency forces to fortify its rule, dividing and conquering via a politics of racist, sexist, and religious scapegoating. Time will tell whether this political formation—one that has been an occasion for critics to revive the term “fascism” in relation to our present—will join analogues in Europe, Asia and Latin America in defining a global ascendency of post-democratic authoritarian capitalism. What we do know is that Trump’s nationalist fixation on domestic “development” is thoroughly extractivist—attempting to exploit all available natural and human resources in an effort to maximize profits at a time of grotesque economic inequality, even while he inspires working-class support with his “America First” rhetoric. Indeed, many unions have misguidedly backed his patriotic-defined rush to drill, mine and build a wall, constituting a contradictory politics symptomatic of today’s dire situation of socio-economic precarity, according to which we’re all led to believe that there is no alternative to sacrificing the Earth if we are to have jobs. That agenda, tied to outmoded industries, needless to say, spells disaster for the nation’s diverse workforce, as well as its civil society, educational system, media, sciences, arts and humanities. Though Trump’s predecessor was certainly no champion on environmental matters—Obama both resisted many environmental regulations and supported an “all-of-the-above energy strategy” that led to the major expansion of oil extraction and pipeline infrastructure in the name of national energy security—the current regime threatens to set us back in incalculable ways.

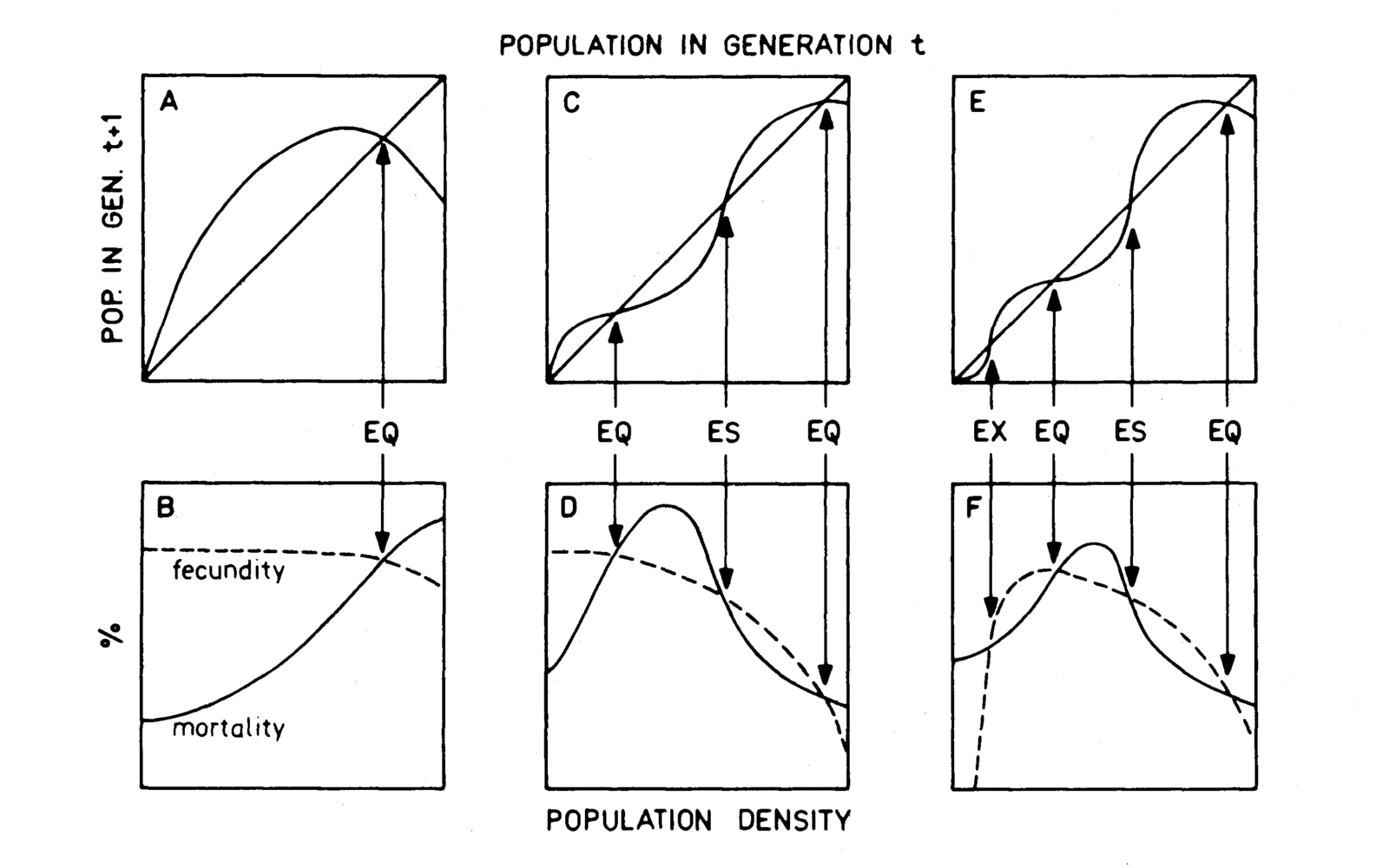

Adding fuel to the fire, this political shift arrives at a time when we have entered an unprecedented geological interstice, when fossil-fueled climate change has yet to deliver its full impacts owing to the temporal lag between cause and effect. Those transformations—hotter temperatures, drought, rising seas, depleted resources, degraded lands and seas, species extinctions—accompany and exacerbate social, agricultural, economic, political, and military crises. Not only will they worsen in the next few decades, but adding in the Trump factor, promise to strike with even more violence and intensity. No doubt ours is the era of a great transformation—or what the writer Amitav Ghosh has recently termed, provocatively, The Great Derangement—through which we (and future generations) will live, dream, and die with more or less inequality and impoverishment, and thus more or less suffering and injustice, depending on how aggressively we confront—or continue to ignore—the current crisis.1 We know that in any case the climate effects will be geographically distributed unevenly, with countries in the global South, those with the least resources, hardest hit. How will future analysts view this historically unprecedented situation, where our political systems are as out of whack as our ecologies are disturbed? When will we recognize that our current growth-obsessed economic system—cloaked in the myths of freedom and American exceptionalism—provides not the best hope for guaranteeing the continuation of life, but is instead the very cause of the politico-ecological catastrophe we now face? If so, how can culture—as the location where enduring social values, where the narratives, images, and sounds through which we understand ourselves, our relations to each other and to the world we live in are created collectively—contribute to sensing and comprehending the risks and dangers of our present order? More importantly, can it generate livable and desirable alternatives? How can the arts provide new perceptions and affects (for instance, those of justice, responsibility, and mutuality) through which life might be reinvented?

Reassuringly, we’re also seeing the growth of major ruptures in the dominant regime, in the US and beyond. This includes the Movement for Black Lives, the massive Women’s March on Washington and spreading Sanctuary cities movement, Indigenous resurgence insisting on land sovereignty and environmental protection, artistic-activist formations contesting petrocaptialist cultural institutions, and the ongoing nationwide General Strikes—each of which refuses to normalize Trumpism, doing so with multiple intersectionalist solidarities between them. And despite the election, the recent past has witnessed undeniable gains, even if near future push-backs are already in motion: Indigenous water protectors at Standing Rock temporarily stopped a nearly four billion dollar oil pipeline from being constructed on their land in North Dakota and threatening their water sources, while activists associated with #sHellNo in Seattle’s port interrupted the oil giant’s plans to drill in the Arctic. Meanwhile, the London-based collective Liberate Tate, part of the international Art Not Oil Coalition, won a heroic six-year campaign to get the Tate Galleries to cut sponsorship ties with British Petroleum, and the New York-based group Not An Alternative organized a public petition signed by dozens of renowned scientists urging museums in the US to sever links with fossil-fuel corporate sponsorship that led to the removal of billionaire oil-heir, rightwing philanthropist, and climate-change denialist David Koch from the board of New York’s American Museum of Natural History. Additionally, radical farmers, climate activists, and artists in western France—building on recent UK-based anti-fossil-fuel occupations such as the Climate Camps—have been successfully defending their territory known as the Zad against the state’s plans, in cooperation with the French construction corporation Vinci, to develop the area with a new airport, and install in its place a radical experiment in commoning.

A tractor parked during a ZAD protest, Fall, 2012.

These are gains to be celebrated, even though they represent a small sampling of practices with lesser or greater stakes, assorted modes of engagement and varying degrees of privilege and sacrifice. Yet all are both exemplary of the spread of popular creative uprisings and joyful rebellions and constitute growing resistance to the current political-economic impasse regarding global climate crisis. Measured over the last twenty years of UN climate conferences, we’ve witnessed nothing less than the complete failure of climate governance to enact policies that would limit emissions to keep the Earth within two degrees Celsius of pre-industrial temperature levels. Indeed, CO₂ emissions are over 50% higher than in 1992 when the UNFCCC was signed at the Earth Summit in Rio by all UN members who pledged to “prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” Twenty five years on, we face an insufferable antinomy between the yearly promises to limit global warming and the reality of our movement toward climate chaos.2 Unsurprisingly, the ultra-wealthy are busy investing in million-dollar silos of escape in preparation for the coming apocalypse, apparently not quite believing policymakers who endlessly insist that climate solutions are compatible with continued economic growth. Meanwhile, responsible members of society have demanded radical system change, such as the climate scientist James Hansen, who disparaged the 2015 COP 21 Paris agreement as a “fraud” for its voluntary contributions to emissions reductions, and has recently, following the last US election, called for nothing less than a new “revolutionary party.”3 With ever greater challenges for our present brought about by the rightward movement of governments toward populist authoritarianism, extreme extractivism, military neoliberalism, and post-political market-based rule, the continuation of petrocapitalism’s suicidal trajectory appears to have no end in sight.4 Yet the resistance is growing, with calls for insurrection sometimes coming from the unlikeliest of sources.

Liberate Tate, The Gift, 2012. Performance at Tate Modern. “On 7 July 2012 Liberate Tate installed a 16.5 metre, one and a half tonne wind turbine blade in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in a guerrilla performance by over 100 members of the art collective. The artwork, called The Gift, was submitted to be part of Tate’s permanent collection as a gift to the nation ‘given for the benefit of the public’ under the provisions of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992, the Act from which Tate’s mission is drawn.” See →.

Defending an autonomous zone, blocking an oil pipeline, invading museums: this turn towards civil action joins a long history of oppositional culture and anti-colonial politics, creating what some have termed “beautiful trouble.”5 Its resurgence is not surprising today. When conventional political routes are shut down—whether corrupted by corporate, illegitimate, or anti-democratic influence —we are left to live according to collectively-determined ethico-political convictions, which leads new questions to arise: How might current formations direct their energies in ways that are long-term, sustainable, and transformative, building on the gains of recent Occupy mobilizations, even while they must operate in an increasingly intolerant political environment? Given the limitations of representational politics, when many demonstrations seem to present the performance of political affects delinked from any appreciable results within the corporate-beholden political process, how can grassroots citizen-led transformation lead to new forms of governance and a transition beyond the current carbon regime including its corrupt politico-economic framework?6 More specifically, how might cultural transformation infuse and direct new political organization, bringing militant and insurrectionary actions into relation with coalition-building and electoral politics—the type of relation between the grassroots street and the politician’s policy room that was glimpsed in the Sanders campaign? These are urgent and uneasily answered questions, yet they must be asked. Yet regardless, as in the above instances, creative cultures of resistance and collective practices are being built beyond the terms of the petrocapitalist order, and in this era of emergency we would do well to consider their significance and how we might contribute to their growth and expansion.

That said, the divides between gallery-based art practices and the abovementioned cultural formations only seem to be growing, which, given present crises, invites the question: What if these practices—none of which are recognized or self-identified primarily or solely as art—were not simply slotted into the category of activism and dismissed as such by those of us in the cultural sector but viewed, discussed, and taught as the most daring, bold, and courageous expressions of what art might be today? Certainly it would not be the kind of art that is commonly validated in well-resourced art institutions and supported by a generally elite and conservative patronage.7 But what if those practices that do garner the greatest visibility in exhibitions and the press—typically dedicated as they are to individualist autonomy, self-expression, duty-free creativity and visual spectacle—were to be seen as covering over a widespread cultural failure at addressing the most significant world-historical event facing contemporary civilization? What if, in the climate-changed future, those most visible art forms will be precisely the ones that will be indicted for refusing or declining to engage with our contemporary state of emergency?

I’m reminded here of the argument Ghosh puts forward, where he notes a fascinating historical conjunction during the years of colonial and industrial modernity when the Anthropocene emerged at the same time as the establishment of modern fiction. Ghosh notes how fiction, in failing to address climate change, has generally relegated the natural to oblivion. One can also note the larger coincidence of the Anthropocene with Western modernism, premised on similar divisions and hierarchies that have broadly privileged culture over nature. Aside from a small array of artists, which is nonetheless growing, the engagement with ecology has been largely absent from modernism and its histories. What if this is precisely the problem from the expanded perspective demanded by the Anthropocene? As Ghosh writes: “Indeed, this is perhaps the most important question ever to confront culture in the broadest sense—for let us make no mistake: the climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination.”8

For just as the scientific basis and sheer complexity of climate change appears to force the latter’s cultural address into the genres of non-fiction, so does it assume a seemingly natural relation to documentary modes in the visual arts. Yet both non-fiction and the documentary are equally liable to derision either within the literary institutions of what Ghosh calls “serious fiction” or by those who celebrate gallery-based art that is unmotivated by referential demands and political direction.9 But maybe it’s the very organization of culture—including the morbid continuation of these hierarchies that place autonomy and freedom above all else—that’s been thrown out of whack, and are yet further symptoms of the great derangement of which Ghosh speaks. If so, then with the examples of blockadia, Indigenous resurgence, climate camps and institutional liberation pointed towards above, maybe we are witnessing not a failure of the imagination, but rather a structural transformation of the conditions of cultural practice—including a blurring of art, performance, media, theater, and architecture—that is adapting to and critically negotiating the shifting challenges of life at the very moment when the reality of the Anthropocene—or Capitalocene, as some prefer—is sinking in.10 These formations are materializing and performing ongoing cultural mutations and disjunctions that, though easily misrecognized, rendered illegible or wrongly dismissed, are enacting the very rupture most needed within our petrocapitalist complex.

Water is Life

The event at Standing Rock represents not only a remarkable Indigenous convergence—building on the Idle No More movement that has energized and networked First Nations across Canada and the Americas in the collective struggle for native rights, treaty enforcement, and self-determination—but also a structural transformation of the conditions of cultural practice. Dedicated to stopping the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on sacred burial grounds and under the Missouri River, the camp was set on protecting the water source for tribal members and for millions of people who live downriver from their campsite.11 All was threatened by the project of the Texas-based Energy Transfer Partners, representing the most visible and recent large-scale investment in the ongoing development of fossil fuel infrastructure and extraction. But this has been more than just a struggle over a pipeline. For Native American environmentalist and writer Winona LaDuke, #NoDAPL represents a “battle for dignity and the future of a nation”—a claim that applies specifically to the Dakota and Lakota peoples (and Native Americans more widely), as well as to us all, for a future of a nation whose character has yet to be determined.12

Marked by its prayerful nonviolent resistance to the brutal onslaughts of police and private security acting in the service of corporations, Standing Rock has also gathered an astonishing array of collective, representational, technological, and performative practices of opposition that are not simply reactive to repression but actively define an alternative form of living together based on trust and cooperation. An amazing array of protest graphics and print designs have been unleashed inspiring and mobilized in collective protest and spread virally online, which draw upon the creative resources of Indigenous artists and their allies.13 Part of that protest has been the inspiring processes of alliance-building, including the event when US Veterans for Peace movingly sought forgiveness before a group of Sioux elders for the US military’s role in the centuries-long cultural destruction of Indigenous peoples. Videos documenting the camp’s tent encampment, built on a non-monetary economy of mutual care and support, have circulated widely as well, along with diverse photographic imagery of courageous direct actions and front-line confrontations with militarized police. Counter-drones have been launched to surveil police encampments and document instances of police brutality. Large-scale mirrors have been deployed that not only shield water protectors, but also reflect the image of aggressive state violence back to the police. These practices of anticolonial visuality produce critical shifts in perception and dis-identification from state narratives of the conflict. They also promote the knowledge—amplified in the widespread publicity of allied social movements such as 350.org—that this conflict, in which the bodies of defensive solidarity assemble against the force of fossil corporate power, is nothing less that the continuation of centuries of Native-American resistance to the practices of state-perpetrated genocide adapted now to the extractivist interests of the authoritarian capitalist present.

While each of these acts of collective mobilization and creative mediation are notable, even more is the convergence of their visual, audible and participatory forms that ruptured the order of contemporary state power. In this case, art—designating the formation of an aesthetics of collective resistance and decolonial self-determination—has been integral to the process of not only cultural survival but also projective world-making. #NoDAPL is not simply a protest over another pipeline; it’s a matter of growing a culture that rejects the priorities of everything Trumpism represents, a reality where everything is up for sale. Yet that significance isn’t typically recognized because, as Cannupa Hanska Luger explains, artist and member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, “the media’s general interest is in ‘struggle porn,’” and “people have missed what is beautiful about [Standing Rock].”14 What is beautiful about Standing Rock is the cultural resurgence of people who have suffered a still-unfolding history of cultural destruction at the hands of settler colonialism, a conflict that is nothing less than cosmopolitical—an event of collective reality-defining status—in its stakes. The central rallying cry of #NoDAPL “Mni Wiconi,” Lakota for “water is life,” or “water is alive,” did not simply infuse all the activity and death-risking conviction at Standing Rock while the camp was active, but glimpses what botanist and Potawatomi Nation member Robin Kimmerer and philosopher and environmental activist Kathleen Dean Moore claim to be “a story that is so ancient it seems revolutionary.” They explain that “[t]he land is sacred, a living breathing entity, for whom we must care, as she cares for us. And so it is possible to love land and water so fiercely you will live in a tent in a North Dakota winter to protect them.”15 That love, that sacredness, that perspective, which views water as life, needless to say, is fundamentally different from the dominant capitalist valuation of oil, and indeed water, as a commodity to be possessed, hoarded, and profited from.16 The decolonization of water enacted at Standing Rock both connects to long histories of Indigenous knowledge and reinvents emancipatory forms of being and ways of relating to one another and to the land.17

Liberating Institutions

The context and achievements of institutional liberation—perhaps most visible in Liberate Tate’s successful six year campaign—represents a struggle occurring within and around art institutions, as well as public science and natural history museums in the case of Not an Alternative, that is clearly distinct from the front-line Indigenous struggles for cultural survival in violent confrontation with the fossil state-corporate complex. These groups nonetheless express solidarities with Standing Rock, and the movement for institutional liberation is likewise dedicated to a politico-ecological transition to a post-carbon future founded upon social justice, the difference being that they start with the emancipation of public cultural and educational institutions from petrocapitalist economics, sponsorship, and propaganda. They expose and target the cultural philanthropy—or “artwashing”—that grants corporations like BP, Shell, and Total a “social license to pollute,” in the same way that others challenge the “greenwashing” that allows some to manipulate the rhetoric of sustainability to disguise unsustainable practices.18 Their central question is also how to mobilize collective forms of direct action towards transformative ends, defined by David Graeber as insisting upon acting in an unjust society as if one were already free, according to one’s ethico-political convictions, as if the desired future is now.19 Operating within the cultural centers of Western state power, these groups refuse the politics of representation alone by enacting unauthorized, or rather self-authorized, public performances of resistance to the fossil-fuel cultural economy.20 The alliance-building activities of these groups effectively draw together scientists, environmentalists, artists, and diverse publics, and point towards the formation of a “collective power” that, according to Jodi Dean, member of Not an Alternative, “mobilize[s] in an emancipatory egalitarian direction, a direction incompatible with the continuation of capitalism and hence a direction necessarily partisan and divisive.”21

With divisive partisanship, solidarity becomes a key term, occurring in the socially impoverished context of social media’s info-bubble economy and of renewed attacks on organized labor. Solidarity proposes an embodied sociopolitical relationality of support and mutual care driven by shared political conviction which, even if it is not wholly unified in every way, is markedly distinct from neoliberal social atomization and the mediascape of managed connectivity and enforced separation. While there is an important moment of negation in these activities that draws participants together, there’s also the creation of an emergent shared culture of positive transformation. While groups are resisting museum security and refusing to endorse its narrative, challenging the financial privacy claims of publicly funded institutions and opposing the extraction of cultural value to normalize corporate operations, they are also charging artistic interventions with the energies of social movements, re-infusing institutions with public interest and pushing museums into symbolic sites where the stakes of collective wellbeing are waged against the narrow interests of financial elites. Not only are cultural private-public sponsorship arrangements suddenly made strange and ethically questionable, but the everyday gestures and unexamined internalizations of such arrangements are consequently made intolerable. Like Standing Rock, this movement preempts the ongoing reproduction of fossil capitalist culture, decolonizing the future from its capture by short-term profit priorities and expanding zones of ecological sacrifice.

As Liberate Tate has explained, their practice builds on a long history of institutional critique in art—from Michael Asher and Hans Haacke in the 1970s to Fred Wilson and Andrea Fraser more recently. Current practice signals its difference from that genealogy in explicitly drawing on the power of social movements in order to connect with their “instituent power”: “[A]ctivist-art’s growing popularity marks an entry of social movement strategy into art’s spaces” as well as infuses and draws upon the counter-publics and undercommons beyond and around them.22 As such, institutional liberation goes beyond merely challenging fossil-fuel sponsorship. At its most ambitious, it joins formations like Standing Rock in defying petrocapitalism and creating “counterpower infrastructure.” As Not an Alternative explains, “institutional liberation isn’t about making institutions better, more inclusive, more participatory. It’s about establishing politicized base camps from which ever more coordinated, elaborate, and effective campaigns against the capitalist state in all its racist, exploitative, extractivist and colonizing dimensions can be carried out.”23

Not an Alternative, Koch is off the Board, 2016.

Blockadia

The Zad, while no art institution, is precisely such a politicized base camp. With resistance against the construction of an airport at Notre-Dame-des-Landes going back to the 1960s when the French government first announced its plans, the conflict heated up once again following periods of dormancy in 2015 when those who live and farm in the area, some 4000 acres of wetlands, fields and forests, were put on eviction notice. Since then they have repelled numerous attempts to clear the area by the militarized police, transforming the technical term for large-scale development zone d’aménagement differé into a zone à defendre. Thousands of participants have since joined the fluid, shifting, and growing movement including farmers, trade unionists, pensioners, radical eco-activists, squatters, engaged activist-artists.24 As the Mauvaise Troupe Collective explain, “the Zad is a space where different ways of inhabiting this world—fully and generously—are invented in the here and now … It is a hope rooted in histories we hold in common, enriched by the momentum of tens of thousands of rebels and relationships woven thick by time … like blazing bearings for the future.”25

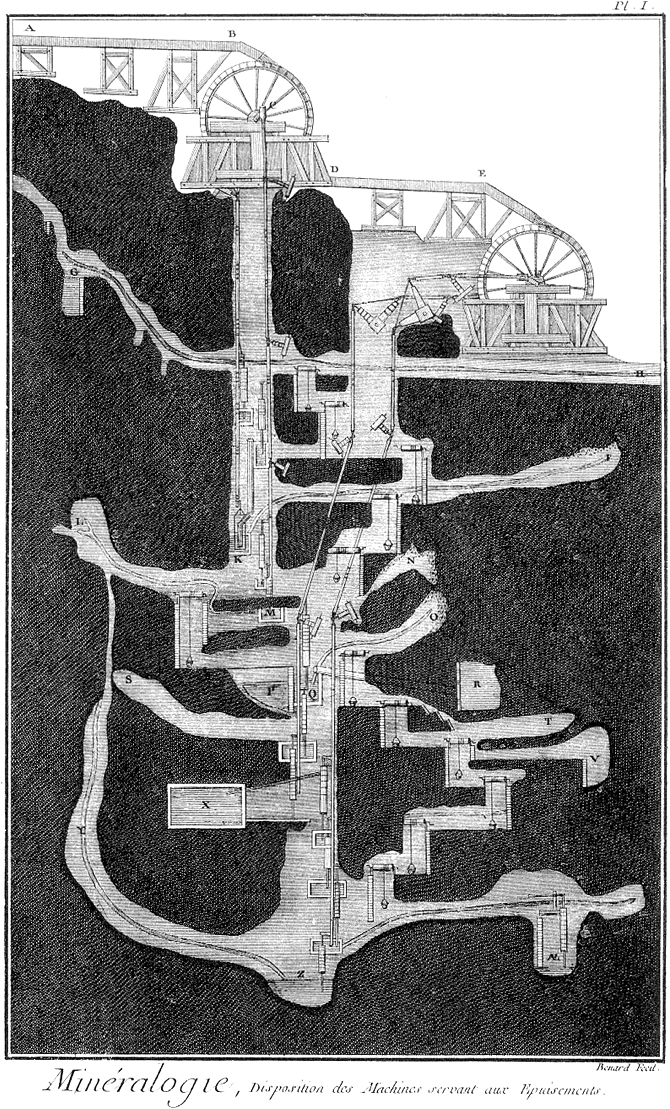

As an experimental environment, the Zad contains informal architecture like huts, yurts and caravans, and recycled materials placed in a bricolage of spatial accumulations for inhabitation or blockade. Residents regularly hold “non-markets” where fruit and vegetables, breads and flour are freely offered or exchanged in barter, organize collective meals prepared to honor guests and guarantee that everyone has a place to sleep. With its bakeries, tractor repair workshop, brewery, banquet hall, medicinal herb gardens, weekly newspaper, flour mill, library and lighthouse, the Zad operates as an ambitious social experiment in creative and noncapitalist collective living. Zadists publish their own books and texts, create images and videos and maintain a website and pirate radio station that will soon offer programs in both French and English. Its inclusive, collective decision-making and communal practices contrast starkly with the authoritarian turn in French and European governmental politics, increasingly beholden to xenophobic fears and neoliberal austerity following the crisis over migration and terrorist attacks in recent years. The Zad figures as a flashpoint in the network of Blockadia, glossed by Naomi Klein as “not a specific location on a map but rather a roving transnational conflict zone that is cropping up with increasing frequency and intensity wherever extractive projects are attempting to dig and drill, whether for open-pit mines, or gas fracking, or tar sands oil pipelines,” or indeed, transport infrastructure.26 Going beyond mere occupation with a short-term goal, Blockadia defines a revolutionary autonomous formation fighting for a society based on principles of direct democracy, gender equality, and environmental sustainability, much like Rojava, the Kurdish radical movement in northern Syria, with which the Zad expresses solidarity.27 As an attempt to “change everything,” the Zad camp figures as a “biopolitical assemblage,” a convergence of bodies and signs, technology and media, spatial architectures and social networks.28 Its existence is defined by the daily practice of creative disobedience and the reinvention of the arts of living.

As Martin Legall points out in a recent article on the Zad, the formation echoes the aims and strategy of the Invisible Committee, the French anarchist collective that advocates the arrest of capital at sites of opportunistic disruption rather than targeting national assemblies and political bodies directly.29 Like the US group Deep Green Resistance, it calls for the formation of underground collectives such as communes, affinity groups and strike forces to advance anti-capitalist revolution in moments of political, social, and environmental crisis. Indeed, as the Zadists have it, “We call for the spirit of the Zad to continue to spread, taking a unique path every time, but with the desire to open cracks everywhere. Cracks in the frenzy of security measures, cracks in the ecological disaster, cracks in the tightening border regimes, cracks in the omnipotent surveillance, cracks in a world that puts everything up for sale.”30 The Zad is therefore far from advocating an exodus or disengagement with the world, but rather connecting directly with social movements beyond itself and mobilizing past potential futures—from the commune, May ’68 to the Battle in Seattle—as a radical inheritance to inspire the creative reorganization of life now and to come.31

The Great Transition

With each new scientific report on the declining conditions of our political, economic, and natural systems, it’s becoming clear that the leading question of our time is not simply how to survive and make life livable in a world of capitalist ruins, but how to stop the progression toward ever greater forms of disastrous environmental transformation and limit the impacts of current capitalist plunder while we still have the chance.32 These are the questions that are driving the contemporary transformations of cultural practice. Together, they underline the imperative of enacting a radical system change that will interrupt the seemingly inevitable movement toward an increasingly deranged future.

The engagements outlined above, in sum, are not oppositional to art, just as they are surely not collapsible into that category. Instead, they draw on a diversity of artistic approaches in their ambitious redefinition of the limits of what creative world-making can mean today. In this context, aesthetics, emancipated from institutionalized categories and commodification, becomes a way to reorganize the sensible realms of experience, rearranging in turn our perceptions and desires, which carries the capacity to reinvent the material, socio-political, and ecological conditions of life itself. All are invested in creative alliance-building and tying art-making to social movements; all are practicing a concerted unlearning of our relations to water as a commodity, to public institutions as privatized spaces of corporate propaganda and to community organization as ruled by the narratives of competitive individualism, market logic and the police. With Standing Rock, institutional liberation and the Zad, we have the collective construction of images and stories of nature’s intrinsic value, of the commons, and of self-determination, initiating a creative break from the current economy of petrocapitalist development. While the Anthropocene does make apparent the necessity of thinking in scales of time and space far beyond the present, and with new ethico-aesthetic imperatives, these movements thwart its neoliberal strands that support geoengineering as the unavoidable technological fix for climate crisis.33 Entering the breach opened up between our current politico-economic order and alternatives, these creative practices unleash “beautiful trouble” in the sense that it describes, on the one hand, a radical reconfiguration of the otherwise conventional notion of beauty, revaluing it to name creative acts that contest capitalist realism.34 On the other, beautiful trouble joins aesthetics to ethics and social justice to climate solutions in producing ruptures from the ruling order, wherein a future of collective ongoingness and liveability is born. The above examples are only the most visible and mediagenic flashpoints of oppositional assembly and occupation in recent years, but they form part of a rising tide of massive opposition wherein we witness the revolutionary energies called for by figures such as James Hansen.

Grounded in scientific consensus, recognizing the near-future threat of disastrous climate change is undoubtedly the best motivation for a “Great Transition” called for by leading voices within the diverse environmental movement to designate a systemic shift in social, political, and economic life toward a socially just, post-carbon future.35 But that recognition, we know, is contingent upon a complex psychology, including diverse forms of social belonging and other determinants of subjectivity that play powerful roles in the formation of knowledge that can lead to action. To enact a paradigm shift in fundamental values—one that may take generations to accomplish, but that begins with the resources of past struggles as set within the emergency conditions of the present—will take nothing less than the building of entirely different cultures. With these creative ecologies of collective resistance, we experience just that: new combinations of images and stories, music and participation, solidarities and sacrifices, wherein this great transition has already been initiated. Now is the time to push it further and advance it into common sense, so that it can empower diverse allies and would-be participants to transform the world as we know it.

Amitov Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

It’s important to note as well that warming is distributed unevenly around the globe: two degrees for some will be four degrees or more for others. See, for example, Forensic Architecture’s investigations of “Climate Crimes” and proposals for a “forensic climatology.” See ➝.

For more on the long history and recent examples, see Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution, eds. Andrew Boyd and Dave Oswald Mitchell (New York: OR Books, 2012); and Disobedient Objects, eds. Catherine Flood and Gavin Grindon (London: V&A Publishing, 2014).

Or as Elizabeth A. Povinelli notes in “What Do White People Want?: Interest, Desire, and Affect in Late Liberalism,” “The global expansion of explosive affect is intensified by the simultaneous expansion of the individual via social media and the tight restriction of the same individual in terms of her imaginary socioeconomic future,” ➝.

See Andrea Fraser, “L’1% C’est Moi,” Texte zur Kunst (August 2011); Hito Steyerl, “Politics of Art: Contemporary Art and the Transition to Post-democracy,” e-flux no. 21 (December 2010), ➝.

Ibid., Ghosh, 9.

One limitation of Ghosh’s book is that he doesn’t consider sci-fi—such as the writings of Margaret Atwood, Ursula LeGuin, Octavia Butler, Kim Stanley Robinson, and China Miéville—as not only part, but leading examples of “serious fiction.” That said he’s clearly holding the conventional literary institutions that maintain such genre divisions to account.

See Jason W. Moore, Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism (Oakland: PM Press, 2016); and T. J. Demos, Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (Berlin: Sternberg Press, forthcoming).

The pipeline, if completed, would transfer 570,000 barrels of crude oil daily from North Dakota to Illinois, connecting fracking wells from Bakken Shale to refineries in the Midwest.

Winona LaDuke, “The Dakota Access Pipeline: What Would Sitting Bull Do?,” Ecowatch (August 30, 2016), ➝.

See, for instance, Just Seeds collective’s portfolio of graphics dedicated to Standing Rock and #NoDAPL, ➝.

Cited in Carolina A. Miranda, “The artist who made protesters’ mirrored shields says the ‘struggle porn’ media miss point of Standing Rock,” Los Angeles Times (January 12, 2017), ➝.

Robin Wall Kimmerer and Kathleen Dean Moore, “The white horse and the humvees—Standing Rock is offering us a choice,” Nation of Change (November 7, 2016), ➝; for more on water politics and Standing Rock, see Divided Films, Mni Wiconi: The Stand at Standing Rock, 2016, ➝; and for a wider background, see the Standing Rock Syllabus, ➝.

Standing Rock, in this regard, enacted the decolonization of water at the very moment of its threatened privatization, and not surprisingly, with Trump’s recent declaration to approve further work on the pipeline, the movement has shifted to an international divestment campaign, to date removing more than $55 million from the leading financial institutions funding the DAPL construction (in fact Seattle’s Affordable Housing, Neighborhoods and Finance Committee just voted to divest $3 billion from Wells Fargo, one the project’s leading financiers). Frances Madeson, “Defund DAPL Spreads Across Indian Country as Tribes Divest,” Yes! Magazine (February 02, 2017), ➝.

See Kyle Powys Whyte, “The Dakota Access Pipeline, Environmental Injustice, and U.S. Colonialism,” Red Ink: An International Journal of Indigenous Literature, Arts, & Humanities (January/February 2017): “Indeed, the ceremonies at the #NoDAPL camps, expressions such as ‘water is life,’ the sacredness of the Black Hills, the leadership of women, and the many other moral claims about plants, animals, and ecosystems that protectors are making arise from the time-tested knowledges of Dakota and Lakota governance systems that preexist U.S. settlement”; and Nick Estes, “Fighting for Our Lives: #NoDAPL in Historical Context,” The Red Nation (September 18, 2016), ➝.

Mel Evans, Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

David Graeber, “Direct Action, Anarchism, Direct Democracy,” in Direct Action: An Ethnography (Oakland: AK Press, 2009): 203.

Examples include Liberate Tate’s Human Cost (2011), the presentation of a human body soaked in an oil-like substance in a Tate Britain gallery so as to signify the biopolitical costs of petrocapitalism’s externalities; Hidden Figures (2014), the group’s collective gatherings around a giant black square of cloth allegorizing and contesting Tate’s bureaucratic and financial opacity; BP or Not BP’s guerilla theater performance of counter-BP publicity without permission before unsuspecting audiences at London’s Royal Shakespeare Theater and the British Museum; and a coalition of groups including Liberate Tate and Not an Alternative arranging an oil spill intervention at the Louvre to challenge the flagship museum’s sponsorship arrangements with oil multinationals Total and Eni at the time of COP 21’s meeting in Paris.

Jodi Dean, “The Anamorphic Politics of Climate Change,” e-flux Journal #69 (January 2016), ➝.

Liberate Tate, “Confronting the Institution in Performance: Liberate Tate’s Hidden Figures,” Performance Research 20/4 (2015), 83; they cite Stefano Harney & Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013) and Michael Warner, Publics and Counterpublics (New York: Zone Books, 2002).

Not an Alternative, “Institutional Liberation,” e-flux Journal #77 (November 2016), ➝.

Mauvaise Troupe Collective, Defending the Zad (2015), ➝.

Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate (New York: Allen Lane, 2014), 294–95.

Ibid., Mauvaise Troupe Collective, 20.

See Anna Feigenbaum, Fabian Frenzel and Patrick McCurdy, Protest Camps (London: Zed Books, 2013); Yates McKee, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition (London: Verso, 2016); and Ibid., Flood and Grindon.

Ibid., Legall; and The Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection (Cambridge: Semiotext(e), 2009).

Ibid., Mauvaise Troupe Collective, 20.

Thanks to the Otolith Group for the term “past potential futures.”

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015).

See the pro-geoengineering position of Stewart Brand et al, “An Ecomodernist Manifesto” (April 2015), ➝; and for a counter-position, Ibid., Demos.

See Ibid., Boyd and Mitchell, to which Jordan was a contributor; the work of the late Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Ropley, England: O Books, 2009); and Richard Smith, Green Capitalism: The God that Failed (London: College Publications, 2016).

Stephen Spratt, Andrew Simms, Eva Neitzert, and Josh Ryan-Collins, The Great Transition: A Tale of How It Turned Out Right (London: New Economics Foundation, 2010), ➝; “The Leap Manifesto,” issued by a broad coalition of Canadian authors, artists, national leaders and activists in September 2015, ➝; and the eco-socialist coalition System Change Not Climate Change, ➝.

Accumulation is a project by e-flux Architecture and Daniel A. Barber produced in cooperation with the University of Technology Sydney (2023); the PhD Program in Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania Weitzman School of Design (2020); the Princeton School of Architecture (2018); and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University, the Speculative Life Lab at the Milieux Institute, Concordia University Montréal (2017).

.png,1600)