In the days of the wheel so much energetic expenditure was used in overcoming friction: a constant drag on progress and perpetuity. Caused by the need to push opposing surfaces of microscopic crystalline mountain ranges over each other, considerable energy was required to make things slip and roll. The frictional resistance of a wheel or bearing was a simple multiple of the weight that was carried. Great resources were expended as axles ground hotly and noisily against their bearings.

In the world you knew, friction was always the same, irrespective of speed. There was no advantage in slowing down. We wanted to increase our income, we were bound to urge things on, to speed things up. Same day, next day, everyday delivery: streams of lorries on the highways. We gritted our teeth, pushed the pedal to the metal, and ground through a hard and smoky life.

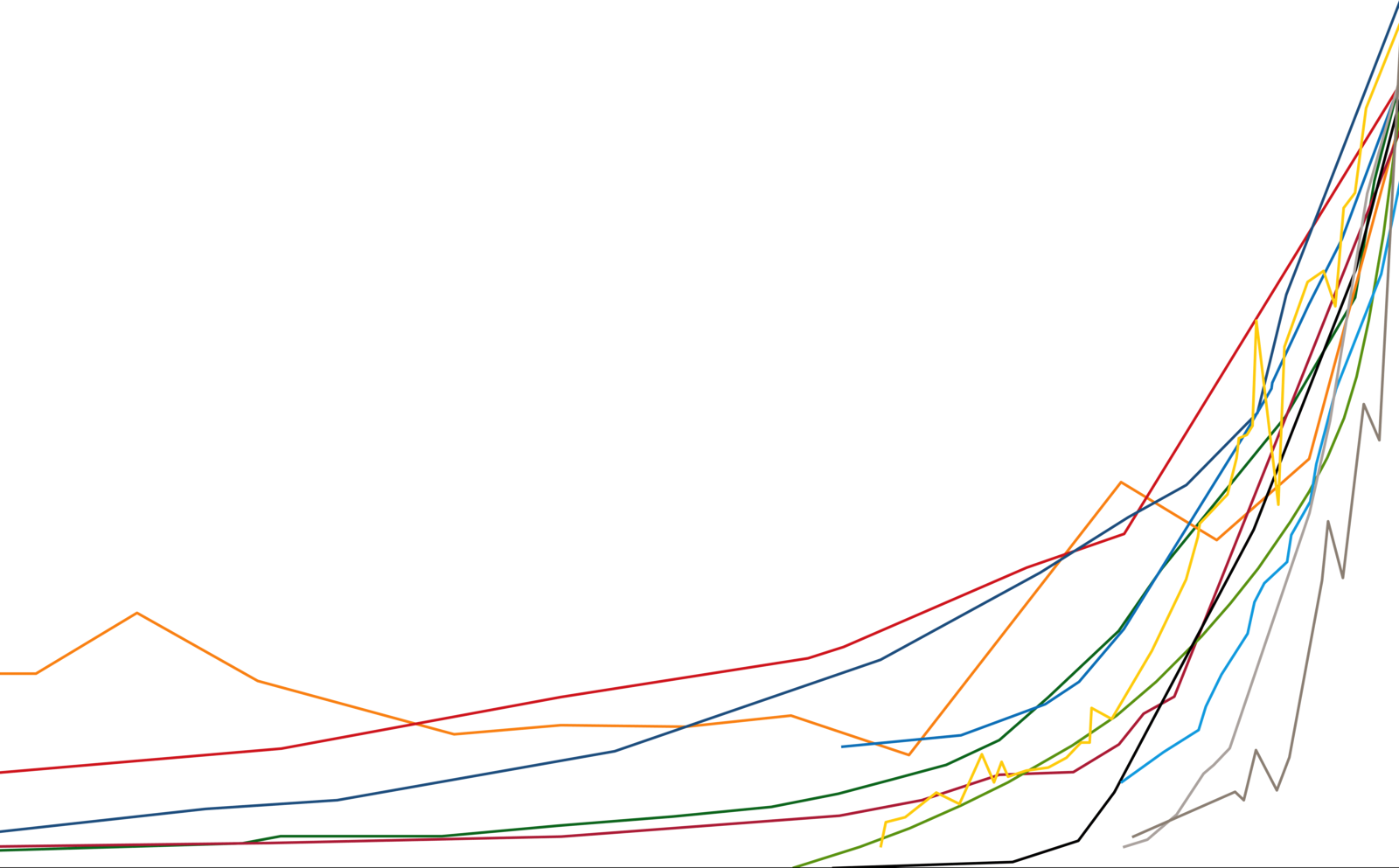

After you left, the region changed. There was scarcity. Fuel was scarce. Not just fuel to make things move, but fuel to make steel and new means of power generation. There were never enough wind turbines. We needed land to grow food and solar farms and fuel crops. Rebellions in mining areas meant lithium for batteries was in short supply. Magnetic trains and hyper loops fought against friction in ingenious ways but were costly to run and maintain. The economy demanded circulation but after 400 years of burning up coal, gas and oil, we were running out of the means to provide it.

Distribution became erratic. Complex systems for food dispersal had never had to cope with an actual lack of fuel before. The computer choreography of logistical distribution networks failed with spectacular disarray. Starvation then violence, then unmentionable barbarity. We’d driven ourselves right to the turning head of an energetic dead end.

The resistance of an object’s passage through water is proportional to the square of its velocity. Speed makes a difference on water. Cut the speed in half and you quarter the resistance. Quarter the resistance and you quarter the energy. Water borne transport favours the long, the thin and the smooth. Tiny amounts of energy are required to gently impel immense tonnages at very low speeds.

The transport of heavy goods on road or rail was outlawed. The furious cyclicality of the wheel would no longer drive us round the bend and it became clear that water had always been the answer.

Tarmac was banished, room only for slick, puddled clay. The tyrannical need for precision in rail or road was exchanged for the sloppy digging and flooding of simple trenches. Water courses were crudely made, but water, standing, sits perfectly level, effortlessly providing a smooth surface for passage.

The ubiquitous drone of distant roads was silenced. Suspensions, brakes, tyres, shock absorbers, all became unidentifiable bygone objects. The terror of collision death, and the knife-edge mortal suspense of a million juggernauts hurtling along a motorway has sunk into the past with other extinct pestilences. Roll bars, airbags, seatbelts and mangled bodies hydraulically cut from smouldering steel car wrecks are recalled with morbid fascination.

Our minds are now dedicated to the honed curves of hydroplanes. Our ideals follow the sliding of liquids over the flow lines of bodies cut from timber’s grain. Our days have poise like the synclastic arches and spars of boat hulls made light and simple as the physics of water flow and static balance are brought together in elegant form. In today’s water borne world speed is the enemy. The slower we are the better we live.

With the new slowness, expectations have changed. Time has changed. Waterborne time is quiet and smooth, comprising long rolling hours that glide by: an ecstatic restraint against excess. Human psychology has adapted too. The narrow eyed, manic grip on the plastic steering wheels of the past has been swapped for gentle palm pressure on smooth wooden tillers. The quiet things, once submerged in a cacophonous world, float back into consciousness. The wan light of back-lit clouds, the wind in the grasses, the chirp and slush of water.

I think slowly about what I want, but now I also have time to think about what I want for others and what they might want. I am prevented from impulsive actions by the time it takes to realise them. I have to think carefully about a new pair of shoes. I need them to last but be comfortable. A cobbler three weeks away made shoes for an acquaintance. Pebble grain leather, oxblood brown, I’ll order from her. I consider the style. While working sometimes I take a break, lie back, close my eyes, and imagine how they will fit. How well they’ll match my clothes. I have time for this. I make my selection, I send my order in writing, and I wait.

The movement of citizens has changed too. If you are needed in another city you pack a book and two changes of clothes for the journey. Canals have taken the place of roads and rails. You travel little but when you do it is a pleasure. You used to call this kind of time meditation, when it had to be deliberately prised from the rest of the day. Now you journey under clean skies in gentle movements through the land, sluicing your mind of worry and flooding your lungs with damp cool air.

Slow flowing time promotes localism. It expands distances. Our small country is now huge and varied, requiring months to traverse. The season and your location dictate what you eat and what you can look forward to eating. These changes have reduced the flow of goods but have made the goods taste better.

Seas are no longer a barrier to internationalism. The frontier of the mode change from wheel to hull or plane no longer exists. We are neither closed nor global. People and things just drift across borders. Bodies come and go on boats, uninhibited by fences and officials, slowed down like thick treacle to an imperceptible pace. No waves or inundations just slow circulation and a sap-like coalescence of races and peoples seeping through our watery arteries.

A waterborne society has emerged. Slowness was the answer to our energetic problems and for many the calming has been welcome. Inactivity, or slow doing, means consuming less, and it is laudable. Non-consumption requires less transportation. We work little, eat and buy little.

We foster friendships and value conversation and humour. We dedicate time to each other. The elders, the youngers, the sisters and the brothers all get the time they deserve. We have more time for love. More time for more loves.

Doing nothing slowly is greatly admired. Consciousness is valued for its own sake and not as a tool to fill pockets, shelves or stomachs. There is nothing better for the soul than an hour sat by a window lost in thought.

But there is a shadow to the lauded slack. Boredom is a malign worm in the minds of many. Boredom breeds trouble, conflict, and irascibility. The prohibition of speed is strictly prescribed. The wheel is outlaw, its temptations taboo. Boredom has bred resurgence in certain parts of the kingdom, where people think of speeding back up. For those of us to whom the moral canal of slowness is trusted, this boredom is a cancer. Society cannot forget where it came from. The authorities are clear on that.

Certain groups have begun to conceal wheels. They fashion motorbikes from old engine parts. They have been seen to roar across the land. The young are particularly susceptible to such heady excess. We had to slow them by force.

Arrests, forced re-education, incarceration. Sometimes leaders must debase themselves for their ideals. Kinder methods were attempted too. We dosed the water with Prozac. It calmed the speedlust, but took a terrible toll on the national libido.

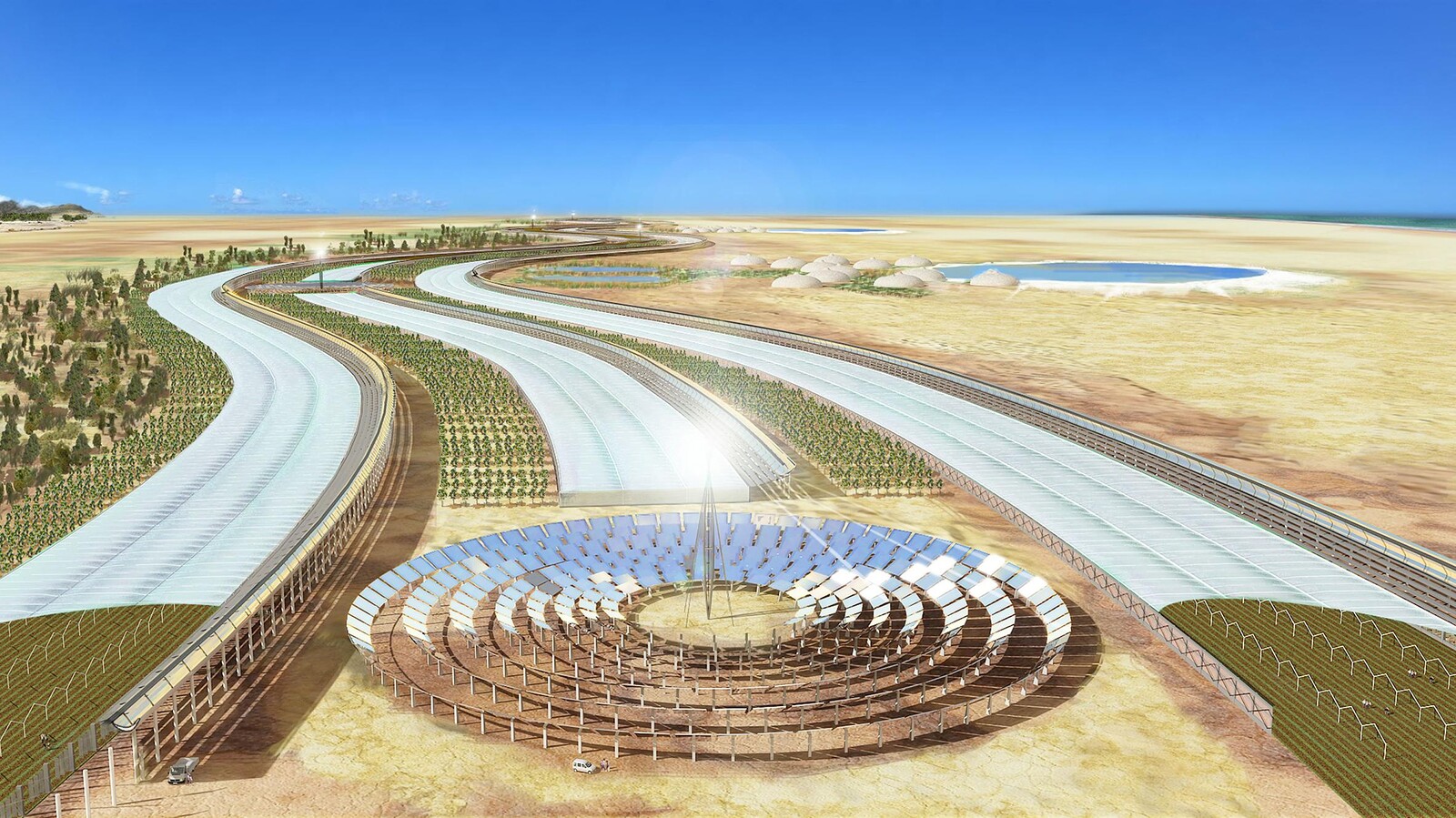

We have come to understand that the young need fulfilling occupations and objectives. A project has been conceived of such scale and awesomeness that it will define our nation’s identity and unify our people. As the ancient societies pacified idle labour between agricultural cycles by the creation of massive monuments, we too will engage in mass creative efforts. We are, as you know, rationalists, so the project will eschew the pointlessness of pyramids and palaces. It embraces logic and restraint and above all characterises our slowness. I am pleased to be able to write to you about this great effort—an aqueduct system—to enclose our major settlements: a series of immense humanmade aqueducts.

Stone is the only material with the strength and availability for construction at such a scale. We forgo the fuel and waste that would make steel. Arches are the only form to span distances in stone. Tall, parabolic red sandstone arches will soar into the air on slender granite ankles. Fan vaults will support the canals at a height far above the canopies of the tallest trees, and disappear into low clouds on winter days. Every piece will be hand carved and reek of human endeavour and of love. I carefully weigh the stresses and balance of these stones with pencil and paper at my old wooden desk so that they will allow barges to soar high in the sky.

Like the Great Wall of China, the aqueducts will be constructed gradually, in a piecemeal fashion by groups of the young. They will be welcomed into new communities of builders, leaving their parochial homes behind to bond in labour and in craft.

The project will span generations, and offer a greater purpose than traditional religion. We offer service to the physical manifestation of our ideals, and this manifestation will be a utilitarian object of permanence and in time, give service to us. We have heard, over the radio waves, that your young are causing you trouble—we would be glad to welcome them here, to offer them a home and a watery path to redemption.

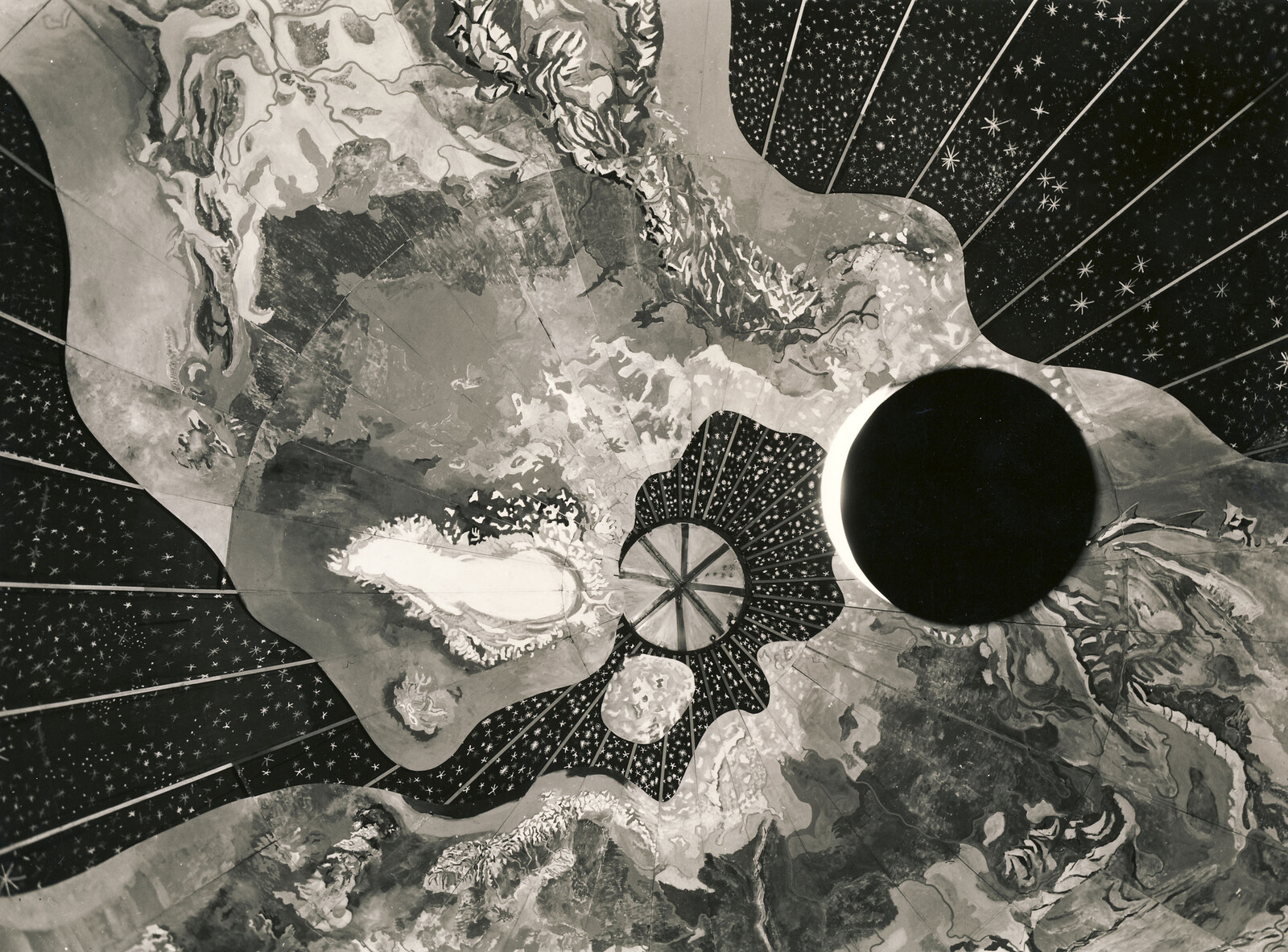

If I rest my pencil for some minutes now, and look into the future, I can see great hubs in the geometric centre of each aqueduct, upon which people will be encouraged to stand. These blessed beings of the future will have unencumbered views of the aqueduct. They will turn around on the centre of this hub and perceive in grateful astonishment the aqueduct at a fixed distance in every direction, its vertical arches linking and enclosing all around.

I hope this transmission reaches you. It is, no doubt, in vain that I wish you could look back down at us from your unfathomable height. How you would perceive that the aqueducts are in fact perfect circles of immense diameter. Virtuous circles of water encompassing and limiting every city—the final giant symbol, visible even from space, that the wheel has been banished forever.

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition, and is supported by the Nordic Culture Fond and the Nordic Culture Point.

This story appears in Gross Ideals: Tales of Tomorrow’s Architecture, edited by Edwina Atlee, Phineas Harper, and Maria Smith (The Architecture Foundation, 2019).

Overgrowth is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the Oslo Architecture Triennale within the context of its 2019 edition.

.jpg,1600)

.jpg,1600)