Located roughly thirty kilometers east from Amsterdam, the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve stretches out over about 5,600 hectares, about 3,000 of which are wetland and water. The piece of land it is situated on, Flevoland, only recently come into existence as a product of land reclamation, the engineering practice of constructing land from sea bed. Flevoland is part of the Zuiderzeewerken (the Zuiderzee works), a large-scale hydraulic engineering system consisting of dams, dikes, and pumps that altogether make up about 180,000 hectares of reclaimed land. Its construction started in 1928 with the draining of the Wieringermeer, and continued with the construction of the 33.4-kilometer-long Afsluitdijk, or enclosure dam, halting the tidal movements of the North Sea from entering the shallow inlet the Zuiderzee. Three more large polders followed, the last of which was drained in 1972.

Such a gigantic infrastructure was built to create a reliable food supply following shortages resulting from the first world war and the growth of major urban areas, as well as job creation and flood protection. But the construction of the Zuiderzee works was narrated according to a frame of colonial conquest. Instead of going overseas or beyond the country’s geographical boundaries to take it by force, as the Netherlands had done for centuries prior, new land was “peacefully acquired” through the use of science, technology, and the “visionary resourcefulness” of Dutch engineering.

The Zuiderzee works were taken up primarily by socialist planners, who together with other politicians and experts perceived the lands to be a “clean slate” on which they could experiment with new and innovative policies and intervention.1 In a spatial sense, this might be an apt description: since the large muddy planes left behind by the water used to be flat seabed, they had no visible cultural historical markers. Emptiness, however, is a slippery concept. Like space itself, emptiness is relational, which means that what is considered empty is dependent on the beholder.2 The idea of uninhabited space as a discovery or a clean slate, a Terra Incognita (“unknown land”) for the exercise of new order, adheres to the deeply colonial imaginary of land as passive, waiting to be used for the production of capital. It relies on the erasure of peripheral knowledge and custom.

The preparation of Flevoland’s polder fields for cultivation sped up in the 1940s and 1950s by distributing seed by airplanes. Kilometers of reedbeds helped evaporate water, further solidifying the soil with their roots, while flaxseed brought oxygen and nutrients to the already fertile soil. The particular patch of land where the Oostvaardersplassen are located was initially planned to be filled with heavy industry, like blast ovens for steel and an oil refinery. Global political and economic conflict in the 1970s, however, called these original plans into question. Furthermore, a substantial part of the area lied particularly low, making it vulnerable to flooding. As a result, the government decided to keep it as a shallow water reservoir. This produced a kind of wetland that was rare in the Netherlands and western Europe. Reed beds and flaxseed started blooming. Rare water and migratory birds began to appear and nested between the pools.

Among paleo-ecologists at the time, there was an ongoing debate about the ecological composition of pre-human landscapes in Europe. It was essential for nature conservation, paleo-ecologists claimed, to have the “correct” baseline.3 Rather than the common theory that Europe was originally covered in forest and canopy, Frans Vera, a paleo-ecologist who worked for Staatsbosbeheer (the Dutch National Forestry Agency), believed that it looked more like a steppe-landscape with open patches and grassland. Unlike many paleo-ecologists, who had to reconstruct this scenario on the basis of historical data, Vera saw the Oostvaardersplassen as an opportunity to actually test it, as if it was a laboratory. Vera began publicizing his proposal to facilitate what he called “spontaneously arisen nature,” to use this new piece of land to create an ecosystem that resembled the Netherlands before “human” history. Elaborate management plans and maintenance strategies for the area were soon developed.

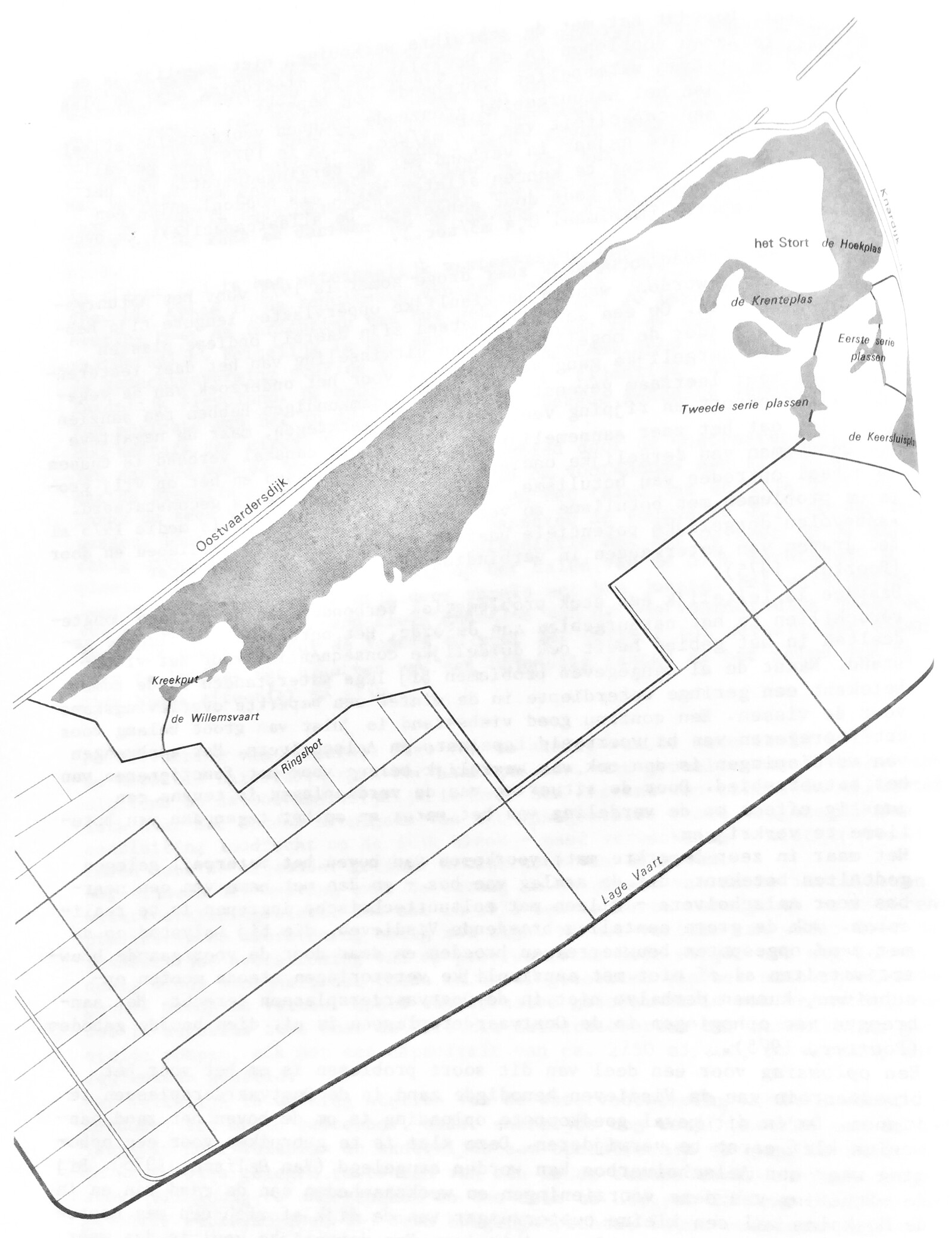

Map of channeled waterways in Oostvaardersplassen. Source: Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning, and Environment, De Oostvaardersplassen. Ontwikkeling en onderzoek van een nieuw natuurgebied in Flevoland (“The Oostvaardersplassen, development and research of a new nature reserve in Flevoland”) (1979). Source: Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer: Centrale Sector, nummer toegang 2.17.03, inventarisnummer 3774.

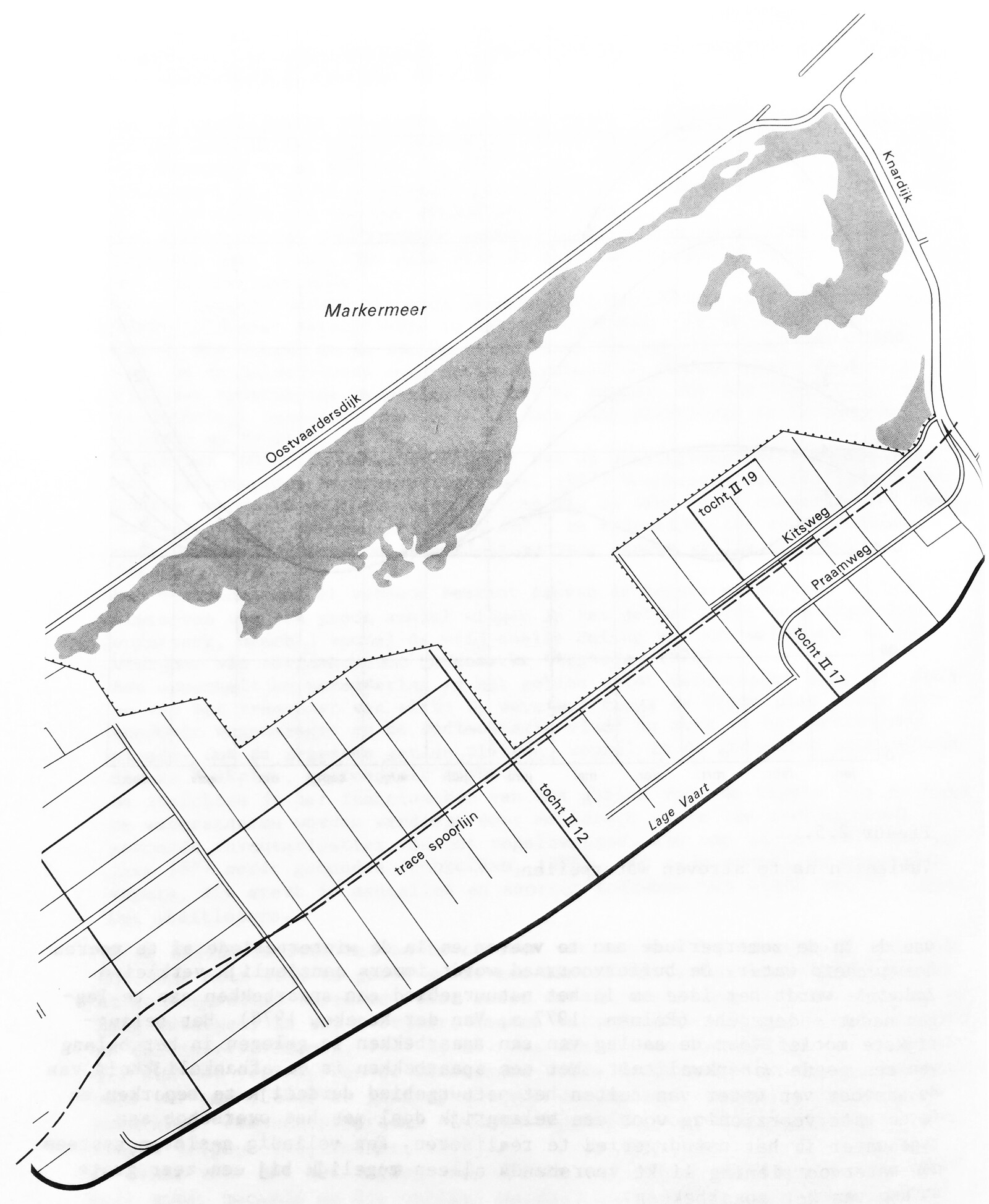

Map of roads constructed in Oostvaardersplassen in 1977 and 1978. Source: Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning, and Environment, De Oostvaardersplassen. Ontwikkeling en onderzoek van een nieuw natuurgebied in Flevoland (“The Oostvaardersplassen, development and research of a new nature reserve in Flevoland”) (1979). Source: Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer: Centrale Sector, nummer toegang 2.17.03, inventarisnummer 3774.

Altitude map of Oostvaardersplassen, 1974. Source: Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning, and Environment, De Oostvaardersplassen. Ontwikkeling en onderzoek van een nieuw natuurgebied in Flevoland (“The Oostvaardersplassen, development and research of a new nature reserve in Flevoland”) (1979). Source: Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer: Centrale Sector, nummer toegang 2.17.03, inventarisnummer 3774.

Map of channeled waterways in Oostvaardersplassen. Source: Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning, and Environment, De Oostvaardersplassen. Ontwikkeling en onderzoek van een nieuw natuurgebied in Flevoland (“The Oostvaardersplassen, development and research of a new nature reserve in Flevoland”) (1979). Source: Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer: Centrale Sector, nummer toegang 2.17.03, inventarisnummer 3774.

Throughout the 1970s, Vera’s views about “right” and “wrong” nature made it into national governmental policies, and in 1975, the Rijksdienst voor de IJsselmeerpolders (National Service for the IJsselmeer polders), the institution that drained and owned the area, declared the Oostvaardersplassen to be a juridically protected nature reserve. The idea was to let the ecosystem evolve with minimal human interference. Nontheless, they immediately started to develop and apply different technologies to shape the landscape in such a way that it would resemble the hypothetical Pleistocene wetlands. They started digging ditches and organizing a water management system that mimicked a “natural” wetland ecosystem.4 To this day, the area still needs intricate water technolocy and continuous maintenance.

To maintain the open landscape, it was necessary to cut the grass and reedbeds. This was first done by Greylag geese, but Vera came up with an additional grazing technology. Large herbivores were brought to Oostvaardersplassen, which were meant to replicate the grazing behaviour of different species of Pleistocene megafauna—notably Tarpan horses and Arouchs—that went extinct in 1906 and 1627 respectively. In 1983, thirty-four Polish Konik horses were introduced and fifteen more in 1987. A herd of seventeen Heck cattle was introduced in 1984, and fifty Red Deer followed in 1992.

Herds of big grazers were meant to be left and fend for themselves as much as possible in order to de-domesticate and re-wild them. Humans, however, were not entirely kept out of the reserve, as it also served a purpose of public education and recreation. Yet, their presence was heavily regulated through a lay out of paths, routes, and fences that dictated where humans could and could not walk. Large animals could be observed from a distance, indicated by signs, and Staatsbosbeheer built observatory huts from which bird watchers could observe the water birds.

The Oostvaardersplassen is now one of the most high-profile efforts of an approach to ecological conservation that ecologists call “rewilding.” The Oostvaardersplassen has been part of the Natura 2000 initiative that is funded by the European Union since 2006, a network of threatened and protected areas that aims to improve the recovery of biodiversity through rewilding practices.5 Still, scientific consensus about exactly how rewilding should be done is all but clear.6 The term circulates among scientists within ecological and biological discourse and has been picked up by environmental activists who put it forth as a solution for biodiversity loss. In practice, conservationists, ecologists, and public institutions work together to create new ecosystems based on historic ecosystems modelled as much as possible after pre-human landscapes.7 Managers of reserves that choose this approach create what they think are the right conditions, and then hope that landscapes and ecosystems will “restore” themselves. These conditions include the removal of human infrastructure, the reintroductions of extinct species, and the minimal interference with populations of flora and fauna.

In essence, the recreation of a “wild” state that rewilding aims for is a purified state in which human presence or cultural history is minimized. “Wilderness,” then, is not only a scientifically slippery concept, but insofar as it is defined by imaginaries of uninhabited territory, it is rooted in the same contested histories of empty land and is predicated by its same mechanisms of colonialism and erasure.8 The Oostvaardersplassen are an example of how it is practically impossible to keep human interference out of rewilded reserves. The wilderness fantasy that it emulates is still heavily planned, regulated, and managed.

The large grazers that were introduced in the Oostvaardersplassen were meant to make it look and behave like an ideal Pleistocene wilderness, but the realities turned out to be more complex. Their herds have expanded; together they grew from a little over 100 to more than 5,000 animals. There are no natural predators of the large herbivores in the Oostvaardersplassen, so an initial policy of culling was developed in the early 2000s. Nonetheless, the herds kept growing, and with a limited grazing area, starvation became rampant. Staatsbosbheer then began shooting starving animals on a large scale in order to maintain what they determine to be a healthy population, which in 2019 was 1,100 large grazers, 600 horses and cattle, and 500 deer. Their so-called “early reaction policy” dictates hunters and foresters to shoot a number of animals before the winter sets in to prevent unnecessary suffering. The selection of the animals that are killed is done according to the “predator model,” which prioritizes the killing of weak, old, and sick animals.9 Foresters shoot roughly 1,000 animals yearly, but in the winter of 2017–2018, after a relatively mild fall and winter and a late onset of harsh cold temperatures in the early spring, this number was almost three times as high. All in all, about 90% of the deaths that season were “unnatural.”

Security cameras in Oostvaardersplassen. Photo: Leonoor Zuiderveen Borgesius.

Since the early 2000s, there have been recurring and fierce debates in the Netherlands about the welfare of the large mammals in the Oostvaardersplassen. Images of the horses, cattle, and deer starving or dying of hypothermia circulate in printed and social media, and have led to questions about responsible management. Along the fences that make sure animals don’t wander off into agricultural or urban areas outside of the reserve are surveillance systems with large lamps and cameras that record anyone who feeds the animals or cuts the fence. Where Frans Vera, other ecologists, the Staatsbosbeheer, and the owners of the area keep insisting that seasonal death—whether of “natural causes” or because of culling—is a naturally occurring and necessary phenomenon in “the wild,” animal welfare organizations and other protesters continue to question the “wild” status of the animals. They argue that de-domestication is impossible in a fenced-in area with not enough room to feed, and call upon the caretakers’ juridical duty of care for what they see as simply domestic animals.

Oostvaardersplassen is an exemplary case study in the collapse of the division between what is natural and what is cultural. The violent histories of colonialism and imperialism that are implied in how the nature/culture dichotomy organizes space as two separate and incompatible domains show that it was a construction all along, and one that served particular political and ideological agendas. The same is true for the notion of wilderness as a more historically specific version of a “true” nature. The fascination with purity that informed the development of the Oostvaardersplassen is met with the irony that the draining of the territory was never natural to begin with.

The land was never “wild,” and neither were the horses and cattle. The Konik horses came from Poland, where they have been said to be phenotypically alike to the extinct Tarpan horse, while Heck cattle are the result of an attempt by the Nazi brothers Heinz and Lutz Heck to breed extinct Ur-oxen back into existence. Both came from parks, zoos, or farms, and the effort to “de-domesticate” them was treated simply as minimizing additional feeding and veterinary care. Them being “wild” is therefore not about the animals’ welfare, but to fulfil an arbitrary fantasy.

When they reduce these animals to scientific objects, ecologists overlook the reciprocity of the human and non-human relationships that were engaged in bringing them into the Oostvaardersplassen in the first place. They ignore the affects on both the animals and the public that these animals’ lives and deaths have as they perform their “wildness.” They also refuse to acknowledge the fact that these animals are workers; they labor for the humans who made and maintain the area in which they live. Their grazing keeps the Oostvaardersplassen wetlands open for rare birds to nest. If that would be taken seriously, they should be entitled to care, to nurturing, shelter, food, and water in similar ways as farm animals are.

The makers of the Oostvaardersplassen accidentally created an unexpected “natural” assemblage of non-human animals and plants. In turn, the charismatic herbivores that were introduced there remain in need of care, evoke human sympathy, and refuse to become “wild.” What this means in concrete terms is for them to figure out, but what is clear is that while they are doing so, the caretakers of the Oostvaardersplassen need to start to take seriously their role of giving care, both to the animals themselves and relationship between humans and animals, which deserve attention, compassion, and nurturing. Its future should be imagined in terms of relationality, reciprocity, and empathy.

How far this conviction of the malleability of land and society went showed also in the population of those new lands, that went according to extremely rigid and eugenic selection criteria. They had to guarantee that only the most genetically, economically, and ideologically suitable people were granted a place.

Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway (Duke University Press, 2007).

Frans Vera, Grazing Ecology and Forest History (Wallingford, Oxon; New York, NY: CABI, 2000), 1–8.

Rogier Kuil et al., Natura 2000-Beheerplan Oostvaardersplassen (78) (Den Haag: Rijksdienst voor Ondernemend Nederland, 2015), 25.

See ➝.

Dolly Jørgensen, “Rethinking Rewilding,” Geoforum 65 (2015): 482–488.

Jamie Lorimer and Clemens Driessen, “From ‘Nazi Cows’ to Cosmopolitan ‘Ecological Engineers’: Specifying Rewilding through a History of Heck Cattle,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106, no. 3 (2016): 631–652.

William Cronon, “The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature,” Environmental History 1, no. 1 (1996): 7–28.

ICMO, Reconciling Nature and Human Interests, Report of the International Committee on the Management of Large Herbivores in the Oostvaardersplassen (ICMO) (The Hague/Wageningen: WING, June 2006).

Where is Here? is a collaboration between Het Nieuwe Instituut and e-flux Architecture following Who is We?, the Dutch pavilion at 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale.