March 25–June 4, 2017

631 West 2nd Street

Los Angeles, CA 90012

USA

redcat@calarts.edu

To begin with, nothing is obvious. Not even the seemingly trivial detail of which corner one would have to go around in the middle of a town in Hungary in order to avoid being discovered by border police. Nothing is obvious: everything comes down to determination, politics, luck, prejudice, tragedy, solidarity… these are what make the claim to the right to move into a reality. Still, although nothing is obvious, there are nevertheless some things yet to be claimed, proven, or found out, which, in retrospect, may seem more obvious than when they were only imagined.

It is obvious from the map examines the role of maps and map-making in the movements of large numbers of people from the conflict zones of the Middle East and Africa toward Europe. The exhibition takes its title from a detailed annotation on a fragment of a map depicting the border between Hungary and Serbia, a map made by people migrating and exchanged among them on social media, a map that instantiates and attempts to realize a basic right to migration. But maps are not only the insignia of agency and the pursuit of a new life. This show gathers three different moments of map-making from the current migration routes leading across or around the Mediterranean in order to chart the complex politics of migratory representations.

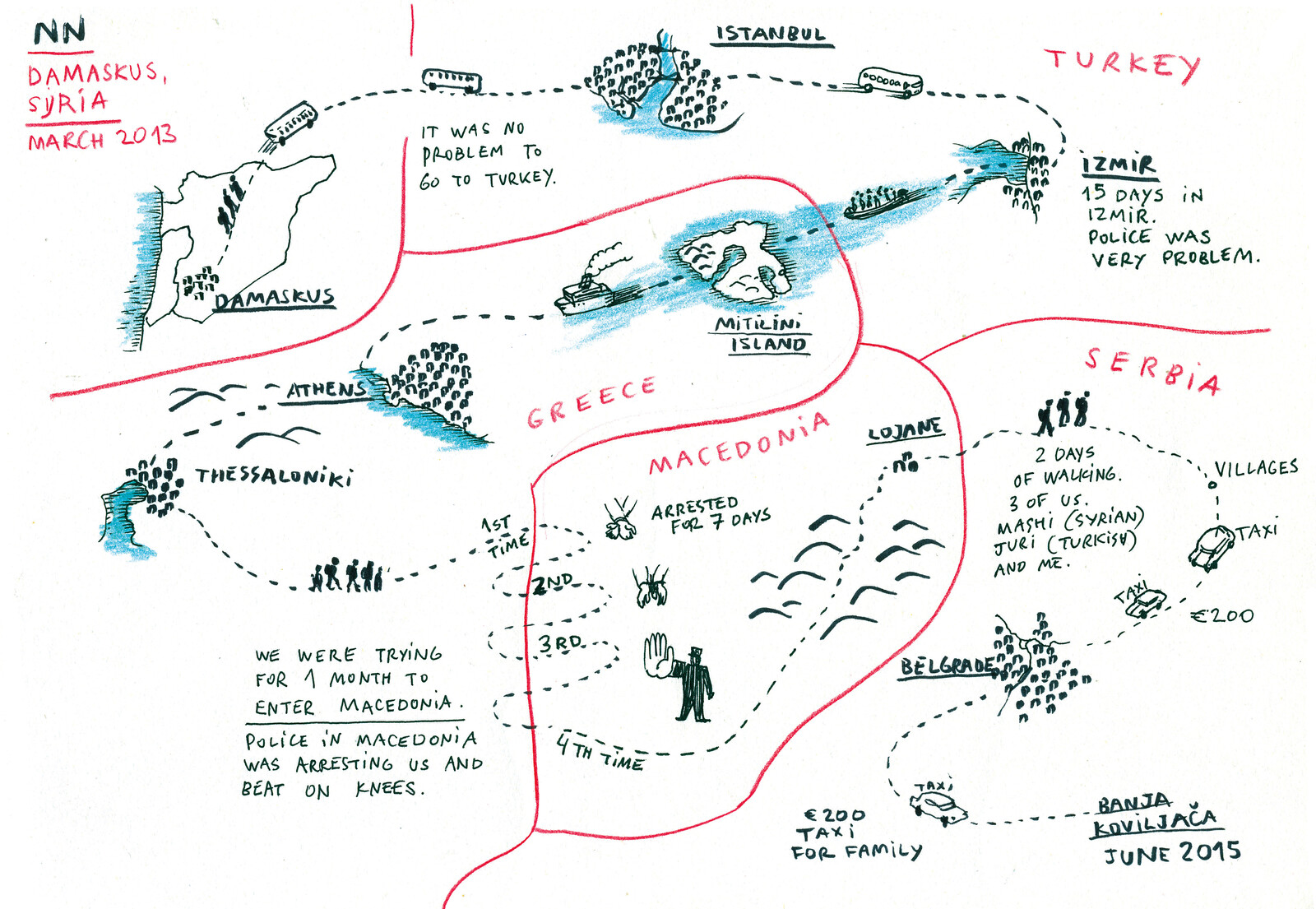

First, the exhibition explores the hidden archive of maps made by people on the move, images and diagrams that are exchanged, distributed, commented on, and annotated by and for the very people who use them. Before and during the journey come the maps; they bear witness and respond to the shifting regimes and technologies of fortification, to the intimidation, weather, hospitality, law, and violence that govern and structure possible journeys. These maps come, one by one and piece by piece, from the crowd en route—many bear very precise indexical traces, whether dropped pins or geotagged metadata, of where and when they came into being. Others emerge after the fact: Djordje Balmazovic from Škart collective, together with the NGO Grupa 484, has been making maps in collaboration with migrants in refugee camps across Serbia, retracing their westbound journeys.

Second, there are the maps that attempt to enforce the regimes constructed by state and regional agencies to assist in the governmental control of migration, whether that consists of directing resources for intervention, tracking migration in real time, or channeling the flow of people and vehicles. “Migration routes management” is a key element in the EU’s border control system. The anthropologists Maribel Casas-Cortes and Sebastian Cobarrubias have studied how these maps function as instruments of control, and not only over the obvious spaces. They show us how, by following migrants’ routes, border patrol and defense agencies have moved beyond the boundaries of Europe and into the territory of “source” and “transit countries.” The borders, now “externalized,” are no longer where we thought they were.

Third, using similar tools but to other ends, the research of Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani (Forensic Oceanography, Watch the Med) painstakingly reconstructs the traces inadvertently left in the Mediterranean by migrant vessels, boats that have disappeared—or boats that have been disappeared, whether by neglect or by rescues gone awry—but whose trajectories can nevertheless be ascertained by gathering and reframing data from a multitude of sensors. These maps too are witnesses, testifying to the criminal regimes that force people into dangerous journeys and that seek to curtail, control and interrupt their crossings.

The exhibition suggests that, these days, claiming to be human and to have rights is linked powerfully to migration. Movement, therefore, is essential to this assertion. These claims are not only made at the border, or in the camp, or at the train station, or at the asylum hearing: the journey itself is a way of exercising and realizing the right and the claim to recognition. This is not without its paradoxes: in the Bogovda camp in Serbia, in response to the question, “why did you make the journey?” a 16-year-old Afghan refugee said, “in search of equality and rights.” Call it “liberté, égalité, fraternité” or “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” these are the very foundations of the modern nation states in which they seek refuge—the foundations which, at the moment, are all too often denied.

Maps, obviously, are not the only ways to represent and propel journeys. The exhibition also includes other images and documents of bodies in motion across borders. Some contributions, such as the videos by Drone Media Studio, are shot from overhead; others, such as the work of Maria Kourkouta, are filmed on the ground; others still, including the work of Tomas van Houtryve, are excavated from deep within the landscape of real-time social media. Most of the material comes from right now, honoring the urgency of the present situation. This, however, can be misleading. As the exhibition also demonstrates, people have been making these trips for a long time, often along the very routes that are now so intensely contested, as the bi’bak collective show in their study of the “Gastarbeiterroute.” Then, there are also the hard facts—the names—of those who lost their lives in these journeys; those who drowned at sea, were stabbed in the streets of London, or died stowing away on trucks or ferries. These other histories, and the claims embedded within them, link the continents and deserve our respect and recognition. Especially since this exhibition takes place less than 200 miles north of a frontier that, for many years up to the present, has experienced similar trajectories and movement.

With contributions by: Bea Abbott and Basel Alyazouri, Djordge Balmazovic (Škart collective), Charles Heller and Lorenzo Pezzani, Maribel Casas-Cortes and Sebastian Cobarrubias, Banu Cennetoğlu & Nihan Somay in collaboration with UNITED, Drone Media Studio, Thomas Dworzak, Grupa 484, Maria Kourkouta, Moises Saman, Can Sungu and Malve Lippmann (bi’bak), Tomas van Houtryve

It is obvious from the map is curated by Thomas Keenan and Sohrab Mohebbi.

This exhibition is funded in part by a grant from Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Additional funding provided by Pasadena Art Alliance.

REDCAT is CalArt’s Downtown Center for Contemporary Arts