Whether as praise or complaint, you’ve probably heard of Indonesian art collective ruangrupa’s sprawling, radically decentered approach to curating Documenta 15. They have pushed back on the most basic tenets of art-industry professionalism including artist lists, commitment to announced public programming, installations being completed before the opening, and apparently knowing what works were going to be included. In a way, that was the point. Their collective-of-collectives lumbung framework dispensed with hierarchical organizational structures as an ideological stance. But curating by delegated committee, or what artist and curator Mohammad Salemy has likened to a Decentralized Autonomous Organization, (1) created a Jesus-take-the-wheel rookie mistake of participatory action, proving that, as on the internet, Godwin’s law applies to the world’s foremost exhibitions of contemporary art. (2) With estimates of around 1,500 artists credited as participating in Documenta 15, the scale and the distribution of responsibility and accountability made it all but guaranteed an offensive work would slip through the cracks. For many, the resulting central display of a work bearing anti-Semitic imagery ultimately made the strongest case for what ruangrupa’s lumbung was meant to be an alternative to—centralized curatorial authority.

If you are reading this, you are likely aware of the institutional crisis sparked by the Taring Padi piece that was removed. The story has taken on a media life of its own, invoking calls to shut down the exhibition and for the German cultural minister to resign, and provoked the resignation of Documenta’s director general Sabine Schormann. (3) Among the voices and opinions chiming in on the nuances of the scandal was German artist Hito Steyerl, who contended in an op-ed that the whole affair suggests that the clock has run out on the “arrogant paradigm of the world art show” and perhaps even globalization as a project of Pax-Americana liberal hegemony. (4) Steyerl’s opinion in the fray is notable given that she is, or was, also one of Documenta 15’s participating artists and by far the most high-profile in a roster that the art-industry establishment largely snubbed for operating outside its purview. (5) Yet convoluted pre-opening media communications meant that for most viewers on day zero of the “Museum of 100 Days” her participation in the INLAND exhibition came as a surprise.

Founded by artist Fernando García-Dory in 2009, Campo Adentro, anglicized to INLAND, links artistic and agrarian labor in a freewheeling and difficult-to-define practice that merges community organizing and leadership development with ecological and pastoral aesthetic inquiry. Among INLAND’s many initiatives: study groups, a choir and canteen, an art academy, a global delegation of nomadic people, a twenty-two-village culture-based development program, a UN consultancy, a shepherd school, a school for peasant leaders, and a school of crafts. In Kassel, INLAND’s offerings are no less bountiful: an exhibition claiming to be an “un-folk museum” at the Museum of Natural History Ottoneum, a summer art academy, a “cave” for curing cheese and a pavilion for selling it. And finally, Cheesecoin, a conceptual collaboration with Steyerl on a cheese-based crypto-critical currency work of five hundred “coins” allegedly circulating in real life and tracked digitally.

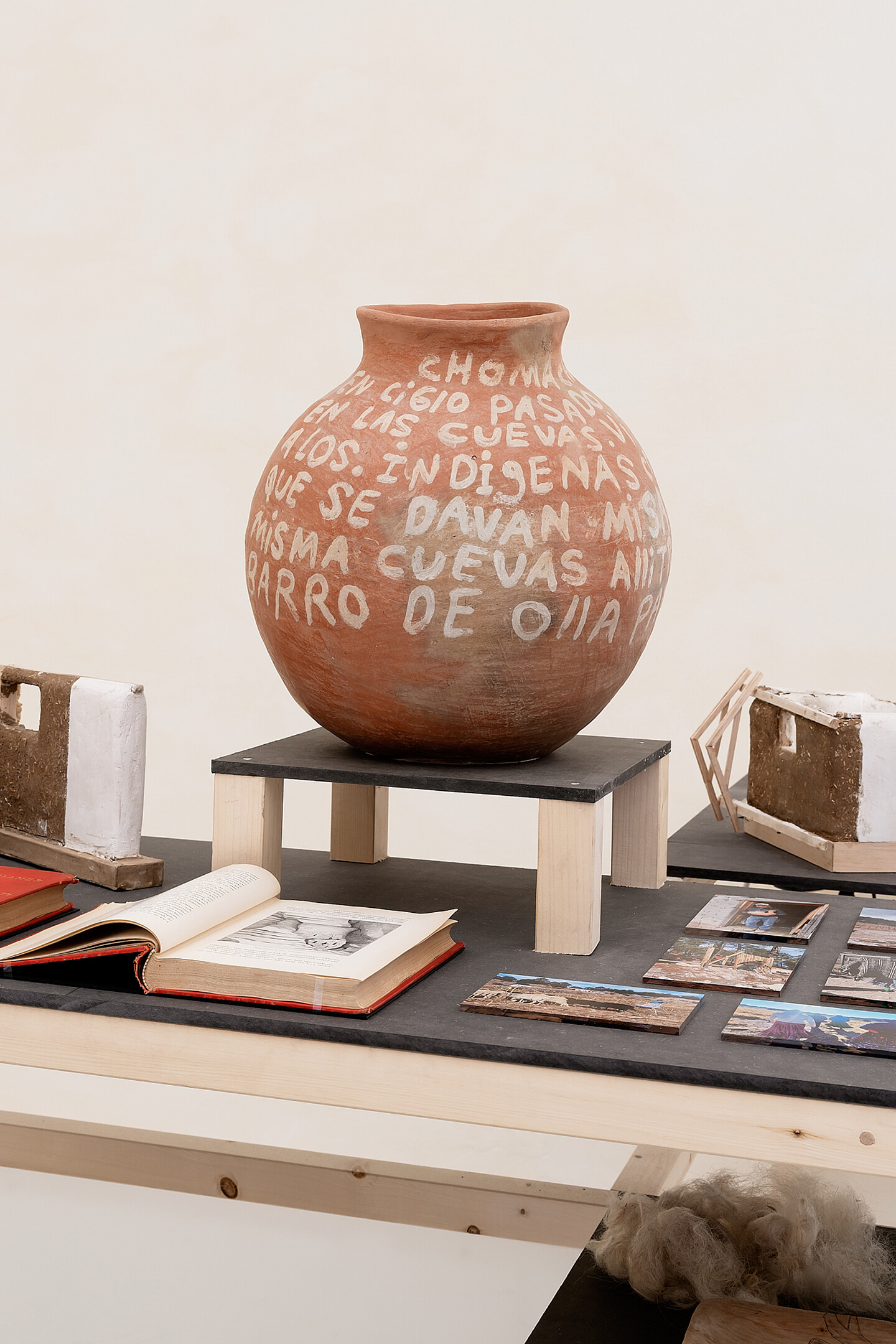

INLAND lists the participation of thirty-two artists, but with sparse wall labels, relatively few objects on display, and a robust public program, with few exceptions, it was hard to know what to credit to whom. In the garden in front of the museum, the Cheese Pavilion operates as a temporary concession stand selling refreshments and INLAND cheese sandwiches—the Wonka-like distribution mechanism of Cheesecoin. Inside the museum, the introductory didactic mentions some of INLAND’s community work but leaves out significant projects, meaning anyone seeking a sense of INLAND’s work and history will have to take to the internet. Rather, the text frames the exhibition as a “cabinet of curiosities comprising knowledge from farmland and forest ecology.” The mostly research-based work, collected ephemera, and artistic exercises are presented in an unfussy exhibition design. Pieces like a small relief of a goat under a tree and an arrangement of branches covered with terra-cotta tile-like figures are displayed directly on the floor. A gathering of shepherds’ staffs lean directly against the wall. A backpack hangs in a corner so casually it’s unclear if it’s a work. The cryptic Cheesecoin collaboration between INLAND and Steyerl is represented by a wall label explaining the project as a “narrative device” alongside a sheaf of Cheesecoin bucks and a table outlining the Cheesecoin-to-sea glass currency conversion. Then there’s the cave.

The cave is, or was, a dark room-sized installation featuring a multiwall projected video work in which an AI animation brings to life the animal figures from Lascaux amid bulbous wall-hung terrariums in which small rounds of cheese sat nestled, ripening between plants under purple lights. One wall featured Steryerl’s video Animal Spirits, which at least superficially stole the show. It was loud. It was sort of high-tech. It was definitely high-gloss. It was funny and weird and invoked reality TV, NFTs, video games, and Keynesian economic theory. It looked expensive and, in an exhibition of research ephemera by outsider artists, gave off the celebrity wattage of being made by an ArtReview Power 100 leader. To this end, it was one of few art-world works in all of Documenta.

But in July, Steyerl announced her withdrawal from the exhibition citing a lack of satisfactory response by ruangrupa to the anti-Semitism allegations. The cave was closed and Cheesecoin ceased to circulate. Yet, if we take INLAND and ruangrupa at their word, these losses of conscientious objection are not critical blows. Animal Spirit may have been the loudest voice in the room but it was far from the most important. This is where things get dicey.

Journalistic integrity holds that if I’m to write about a work I need to experience it, so here’s where I have to come clean. I can’t write about the most important part of Documenta 15 or INLAND’s participation in it because the whole point of this edition is public programming, and I wasn’t there for it. Welcome to the shadow side of the lumbung.

A central aim of ruangrupa and INLAND’s work is a desire to square off with capitalism’s orientation to time and geography as device of value extraction. Both have been clear that their interest is in building community, activism, and experimental inquiry. Objects on display, which most people equate with capital-A art, here are really just pretext. So, with the true focus on public programming and participatory action, none of which had yet to transpire during the press week, all the presentations were somewhere between zero and roughly eighty-seven percent ready, depending on what one considers “the work.” The effect was the feeling of arriving to social-justice art summer camp, but a week too early and not necessarily invited.

This community-action oriented work, which critic Ben Davis dubbed “international NGO aesthetics,” makes sense as an attempt to contend with the way that the commercial art industry is intertwined with the realities of cultural-institutional operations. (6) It’s no secret that the histories and funding needs of museums and biennials have long made them complicit actors in systemic social ills by absolving the reputations of states and philanthropists whose wealth has been gained at significant expense to civil societies. In their curatorial statement in the Documenta 15 Handbook, ruangrupa is explicit: “We learned from the permanent staff that has produced previous editions that most of the artworks exhibited are sold backstage by gallerists during the hundred days of the exhibition and shipped to the collectors afterwards. We decided to move this to the frontstage to make questions about economy, ownership, labor, and exchange a matter of culture.” (7) But by offering a summer of conversation, bearing witness, and extended hanging out as an alternative to commoditization and commercialization, ruangrupa also created a quinquennial that is structurally out of sync with the media economy.

Setting aside for a moment the question of ruangrupa’s responses to the complexity of the anti-Semitism accusations leveled against them, the second-order effect of the collective’s focus on durational community work is that it created a vacuum of messaging. Sadly, no publication is going to pay a journalist to spend a whole summer reporting on public talks. There’s no market for a return on that kind of investment. (Though, thanks to the market dynamics of scandals maybe now there is.) Similarly, art-writing honorariums don’t come close to covering the costs of texts that require travel for three days, much less three months. As it is, every article written by someone other than a staff writer is subsidized. Likely by the author.

I bring up something as crass as the economics of media amid this complex cultural debate to emphasize how the business incentives of press are shaping the conversation. A lot of work at Documenta will go unconsidered in public record because it demands a relationship with time that isn’t economically possible. So, when Documenta 15 opened exhibition halls repurposed as not-yet-occupied community centers, classrooms, and daycares, the exhibition left journalists with relatively little but scandal and scale to talk about. On the one hand, this vacuum exposed how media, as an ad-based business, is imbricated with the art market: it’s fairly easy to write about objects, which also happen to support commercial art enterprise. It’s a lot harder to write about conversations that haven’t happened yet, which don’t. On the other hand, it revealed the degree to which media in the attention economy generates feedback loops of stories that ultimately make their own meaning.

Documenta 15, also known as Lumbung 1, was not designed for the press or the regular crowd of art industry insiders. That was a big part of what made it so refreshing. But as the hundred days of nongkrong, or “collective hanging out,” wear on, it’s becoming less and less clear who exactly it was designed for. Afterall, it’s not just members of the press who can’t afford to dedicate a summer to attending public programming far from home. INLAND does make a gesture toward inclusion by offering videos of their panels on YouTube. But the video of the first panel again highlights questions of access and audience. The hour-long handheld cellphone-recorded video shows about six people attending a talk with chairs for roughly twelve out in front of the Natural History Museum. At one point, a man off-camera, who sounds sincerely interested, tries to join the audience listening to the conversation between García-Dory and ruangrupa member Farid Rakun. García-Dory patiently explains to the man that since he’s not part of the INLAND academy he can’t stay. The exchange heightened the sense that in this edition the participating collective-of-collectives are both the artists and their own audience, making this Documenta structurally more insular than it alleges. In this light, the kumbaya rhetoric provokes questions about how much inclusivity is necessary to count as community engagement.

In the case of Documenta 15 specifically, and even in light of Germany’s complicated relationship with its own past, I’m not fully convinced that the issue, as Steyerl argued, is the “arrogant paradigm of the global art show.” Lumbung 1 tested a hypothesis for the kind of art global intersectional emergency calls for. Grappling with systemic challenges using activist aesthetics but without engaging policy makers raises relevant questions about the power and limits of art to make change. It reveals that “the public” is not pure. Centering community engagement opens the door to all kinds of decency and damage. Don’t we have systems of leadership, government, and curators to protect us from ourselves?

No doubt, it was naïve of the organizers to think that they could make Documenta their subject of inquiry by limiting their critique to market infiltration. Certainly curator Julia Voss’s research in the 2021 exhibition at the Germany History Museum which revealed the Nazi affiliations of members of the institution’s founding team, and the lasting mark it left on German art history heightens the charge of the painful imagery in the Taring Padi piece. (8) Yet it remains true that the violence of late-stage capitalism daily foregrounds increasingly alienating states of emergency that make it difficult to survive today much less dream of futures or contend with pasts. Against the backdrop of extreme wealth inequality and planetary destruction that is already disproportionately affecting the developing countries that so many of the Documenta 15 artists hail from, the contemporary art industry’s relevance has largely drifted to luxury commodity and branding. In this context, ruangrupa’s attempt to center underknown global practices that reassert the primacy of collaboration and communal experience remains meaningful. The scandal, as much as this gesture, invokes complex questions around the ambiguous ways local and global pasts and futures continue to messily inform one another. We shouldn’t turn away from either.

For decades we’ve been stuck in a postmodern shell game that swaps culture for commerce, impoverishes public space, displaces populations, and creates yearning for connection. Maybe the nerve that Documenta 15’s collective-of-collective shortcomings touched was related to the way that it revealed how the institutionally sanctioned summer of nongkrong vibing felt great but also turned out to be merely palliative against the systemic challenges they contend to take on. I want to hope that this turns out to be a time-horizon question. Perhaps we are just at the beginning. After all, this is Lumbung 1.

For now, it calls to mind a tongue-in-cheek line from Steyerl’s now-shuttered Animal Spirits: “All artists fail the interview and the Reality TV show goes ahead….”

(1) Mohammad Salemy, “Antisemitism is the least of Documenta Fifteen’s Problems,” Arts of the Working Class, →.

(2) See →.

(3) See “Head of top German art fair resigns in anti-Semitism row,” Al Jazeera, July 16, 2022, →.

(4) Hito Steyerl “Context is Everything Except When It comes to Germany,” Triple Ampersand, June 4, 2022, →.

(5) Kate Brown “Documenta Presents an Invigorating Alternative to a Market-Driven Art World. Maybe That’s Why the Industry’s Establishment Has Largely Dismissed It,” Artnet, July 1, 2022, →.

(6) Ben Davis, “Documenta 15’s Focus on Populist Art Opens the Door to Art Worlds You Don’t Otherwise See—and May Not Always Want to,” Artnet, July 6, 2022, →.

(7) ruangrupa, “From Mini to Akbar: We Are Not in Documenta Fifteen, We Are in Lumbung One” Documenta 15 Handbook (Ostfilderm, Germany: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2022), 27.

(8) Maximilíano Durón “New Research Shows that Former Documenta Advisor was Member of Nazi Paramilitary Organization” Artnews, March 12, 2021, →.

Kim Córdova is a student the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where she is studying contemporary art and public policy. She is a graduate of the Programa Educativo Soma in Mexico City and College of Creative Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. In 2021, she was named an Eisenhower Fellow.