Field Notes: Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill in “The Milk of Dreams,” 59th Venice Biennale

by Leo Cocar

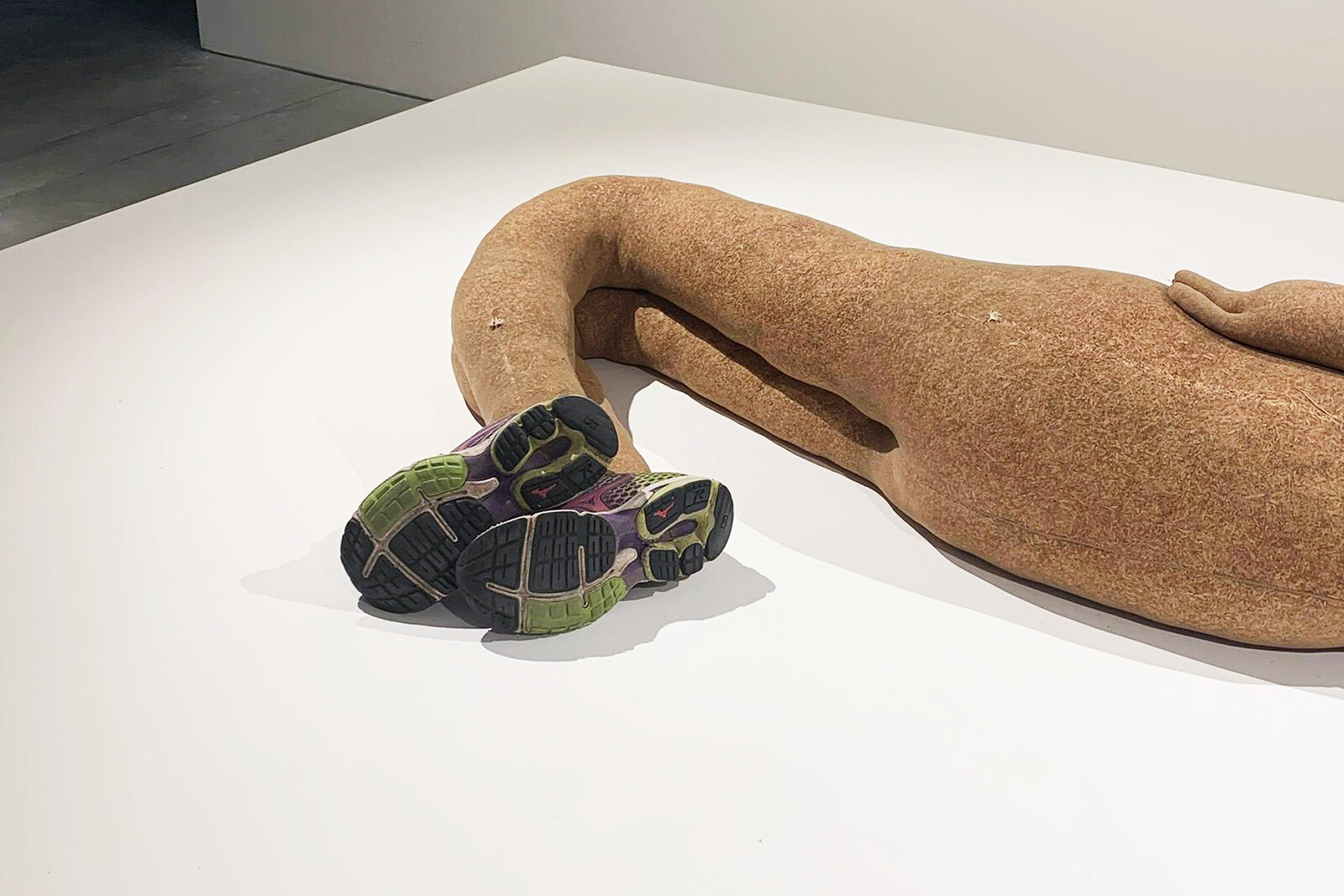

Ducking into the Central Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale, the scent of the city’s slightly fetid saltwater and the Giardini’s sunbaked paving stone gives way to a heady mix of sweat and duty-free fragrances. Passing through the high-vaulted entrance of “The Milk of Dreams” and into the side galleries, a new smell lingers in the air—tobacco. It is faint but undeniably present, flitting in and out of perceptibility; its notes are bitter, medicinal, and earthy. This aroma is not the byproduct of a tourist packing too much rolling tobacco but from a sculpture by Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill. Titled Counterblaste (2021), the work takes the form of a person-sized human–rabbit hybrid figure constructed out of pantyhose stuffed with tobacco and posed in the manner of a reclining Buddha before entering nirvana. The figure’s serenity, however, is interrupted by eight swollen breasts jutting out of its chest and the charms stuck into the rounded, bio-organic contours of its body. A pair of purple Mizuno running shoes suggest the human–rabbit’s “athleisure” lifestyle—commoditized bodily performance masked as relaxation. Hung behind the rabbit chimera are four wall-mounted works from Hill’s Spell series (2018–ongoing), small, abstract works on paper painted with tobacco-infused oil and studded with street ephemera.

Within the grander scheme of “The Milk of Dreams,” Hill’s works is both apt and refreshing. One of the exhibition’s major conceptual underpinnings is an interest in a larger historical trajectory of art production that seeks to undo dualistic world views. As the curatorial statement suggests, the tripartite crises of ecological disaster, technological pressure, and social breakdown have blurred ontological divides. Human and non-human life, machine and flesh, the body and the world are categories much more intertwined than was previously conceived. These conceptual binaries have not only come undone in the face of socio-technological change, but historical consciousness of these categorical “undoings” has been undeniably prescient in understanding how deeply embedded into the web of life we really are.

Frankly, it is exciting to see these discourses being presented to the Biennale’s wide and varied public (at least, that is, by art-world standards). One the show’s major successes is showcasing the ways in which many ideas that have a certain currency in today’s art discourses—the decentering of humans as Earth’s privileged species, for instance—are not recent debates but millennia-old concepts in the so-called “non-West.” Still, certain works, complex and powerful on their own, risk slipping into dangerous discursive territories in this curatorial framework by equivocating Earth with a notion of womanhood defined by reproductive organs, geographical belonging as defined by ethnicity, and easy myths of ecological purity. What of gender as a process of transformation? What of the Earth as fanged and agential?

Hill’s work takes up ideas of categorical ambivalence in its use of Indigenous knowledge systems. Tobacco, for instance, does not situate Counterblaste within a primordial past but rather, as material and signifier, provides a poetic point of departure. Other critics of Hill’s work have noted that tobacco embodies a double life: in Indigenous communities, it is simultaneously a spiritual material, a gift, and an object of trade that resists any of the impersonal calculations of capital. Conversely, within settler capitalism, tobacco is a commodity like any other in a marketplace ruled by the value-form. What Hill’s work hints at is the way the settler state is fundamentally indebted to Indigenous knowledge, an exchange that occurs through violent forms of institutional legitimization or delegitimization. The title Counterblaste takes its name from a seventeenth-century treatise by King James I that disdained tobacco as a habit derived from “barbarous Indians.” Of course, the settler state embraced tobacco to suit its own ends, with the plant-cum-commodity playing a crucial role in the economy of England’s North American colonies. This process of “commodifying the subaltern” continues to play out today, for example, in the branding of American Spirit cigarettes. Then as now, the settler state is not shy about profiting off the colonized.

On the topic of blurred lines in our hazy present, tobacco evokes issues of identity. Hill noted in an interview with Public Parking that as a Métis artist living and working on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, and Squamish nations—or so-called “Vancouver”—tobacco and its multifaceted role as both gift and trade object have survived as a cultural practice in her life despite the ongoing violence of settler colonialism. (1) Temporality and bifurcation are crucial elements of the settler project, in that colonial discourse legitimizes the settler state by placing Indigenous peoples in the past and the colonizer in a more advanced future. Indigenous subjectivity, however, is no less “authentic” in the contemporary Canadian metropolis than in an imagined precolonial territory, and in the face of erasure and suppression, Indigenous epistemologies continue to thrive. Counterblaste’s Mizunos further trouble any attempt to temporally or culturally purify Hill’s work: if colonization is a process still ongoing, Indigenous resilience is right there with it. Spells suggests an environment in which the figure of Counterblaste acts. Hill’s Rauschenberg-esque combine works rematerialize the topography around the artist’s studio, illustrating highly subjective understandings of space within the confines of unceded territory. If the settler project is contingent on the robbery and privatization of land, what does gathering and wandering look like in a world of fences and CCTV?

In Hill’s work, tobacco figures time as flowing and continuous rather than segmented and crystalized and thus attests to the continuance of colonization and poses a potential threat and alternative to settler capitalism. Hill has stated that she began working with tobacco in art school due to an interest in creating work that could be smelled rather than seen. (2) What she noticed in turn was how scent conjured wildly different memories of the same substance: the scent of tobacco evoked ceremony for Hill but corporate greed for her classmates—a sensorial point of contestation. (3) As psychologists have noted, smells are conditioned stimuli that are capable of changing one’s mood, depending on the memory associated with them. (4) Hill’s use of smell could be understood as a subtle jab at European epistemologies and Western philosophy’s historical tendency toward ocularcentrism. (5) The evocation of memory through scent was something I felt immediately: as a child comforted by a perfume of patchouli and secondhand smoke at my grandmother’s (whose cigarettes were purchased from a gas station called “Mohawk”); as a late teenager sharing a cigarette and swearing I am in love. Hill’s work compels me, a settler, to interrogate these associations and how my tobacco memories figure within the processes of colonization and resistance. Paraphrasing slightly, Hill’s work poetically materializes something my friend Stef said recently that really struck me: “Colonialism is not an issue of then or now but rather always—but most importantly not forever.”

(1) Micaela Dixon, “Tobacco, Energetic Fields, and Indigenous economies: in conversation with Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill,” Public Parking, December 3, 2020. See →.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Rachel Hertz, “Do scents affect people’s moods or work performance?,” Scientific American, November 11, 2002. See →.

(5) Katarina Rukavina, “‘Ocularcentrism’ or the Privilege of Sight in Western Culture. The Analysis of the Concept in Ancient, Modern, and Postmodern Thought,” Filozofska Istrazivanja 32, no. 3 (2013): 539-556.

Leo Cocar is a cultural worker and student from the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, and Squamish nations. Currently, he is pursuing an MA in curatorial studies at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College. In his spare time he enjoys cooking and watching UFC. His writing has appeared in e-flux, C Magazine, and Journal.FYI, among others.