Office Hours: Natasha Marie Llorens: Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm

1. Why did you decide to go into teaching?

When I started teaching art theory at the Cooper Union in New York, I was trying to manage the cognitive dissonance of being a graduate student at Columbia University and an independent curator. I needed a space to unlearn what I was learning as quickly as possible, and Cooper students were very good at forcing me to question my assumptions about knowledge. A year later, I took a position teaching curatorial practice at the New School for similar reasons: the classroom offered a place to think about what exhibitions could or should be that was more experimental and dynamic than the art world I had access to in New York at the time. These were not my first teaching experiences—they constitute the moment when teaching theory to artists and curators crystalized for me as a political practice.

2. What drew you to your school and what is your teaching philosophy?

The Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm is at the crossroads of competing definitions of art education. On one hand, it is still structured according to the old European model, which is centered on workshops and students from different levels of education working together under the direction of one professor. This model privileges the freedom to shape one’s education in a very broad sense. On the other hand, Royal Institute of Art is transitioning to a model of art education oriented more toward research and away from medium-specific training. I was drawn to the possibility of working with students who possess the confidence and the tolerance for ambiguity to choose the kind of openness offered by the older model yet are open to the idea of abandoning the autonomy of the art object and the solipsism that so often comes with that idea.

The question posed by this transition for someone responsible for art theory is: How can educating artists in theory contribute to a curriculum centered on aesthetic freedom and not simply enforce professionalizing academic standards for the use of language and history in the arts? The fact that this was still an open question at the Royal Institute of Art was irresistible to me, frankly.

3. What theory and art history do you consider most essential for your students? What artist or artwork do you refer to most often?

It is essential that my students read. It is essential that they feel safe enough to read complex things carefully and with vulnerability. And it is even more important that they develop the confidence to disagree with the authors of complex, genuinely argued texts. That is the sword I will fall on. Further, we who teach in art schools have a profound responsibility to equip all our students with an embodied understanding of critical race theory and intersectional feminism. They will not survive ethically or intellectually as artists if we fail in this respect.

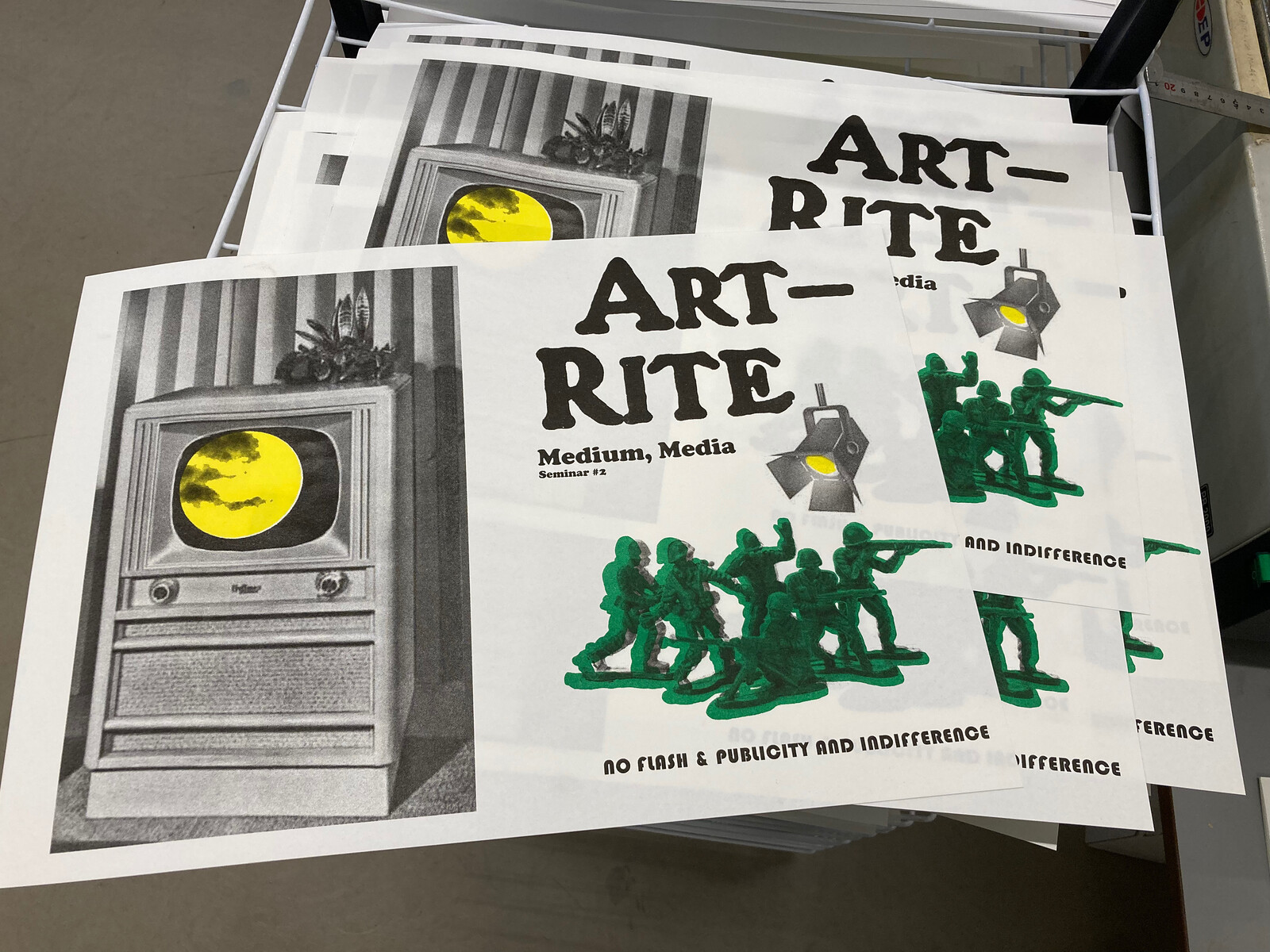

I teach what I’m reading or what is relevant to the students I have this year. A partial version of that list right now: Lorraine O’Grady’s Writing in Space; Melody Jue’s Wild Blue Media; Eyal Weizman’s slim volume, The Roundabout Revolutions; Kara Walker destroying Andy Warhol in an edited volume of artists’ writing published by Dia Art Foundation; Nina Valerie Kolowratnik’s gorgeous argument about indigenous models of knowledge in The Language of Secret Proof; Thomas Keenan’s 2002 article on “the media” and the siege of Sarajevo, “Publicity and Indifference”; and Arkady Martine’s pair of queer science-fiction novels about empire, language, and fungi, A Memory Called Empire and A Desolation Called Peace.

Read more of Natasha Marie Llorens’s Office Hours on School Watch.

Office Hours is a new questionnaire series that gathers insights on teaching from artists. In response to ten prompts, educators reflect on the discourses and approaches that animate their teaching, share their visions for the future of art education, and offer advice for students navigating the field of contemporary art.

School Watch presents critical perspectives on art and academia. Featured profiles, surveys, and dialogues consider education in fine art, curating, and critical theory, as well as the ideas and conditions that influence practice.