Learning What Can’t Be Taught: Reflections on Art Education through the Story of Six Artists from China

by Anthony Yung and Özge Ersoy

When Lu Yang was a second-year graduate student in the New Media Art Department at China Academy of Art in 2008, she made a series of elaborate diagrams of devices that merged machines with animal and human bodies. One of these works, BCMI Reverse Monitoring – The Ultimate Learning Terminal, shows a device designed to enhance human learning efficiency. Imagine this: you are strapped to a gray office chair with belts, your body movement reduced to a minimum. You wear a cap that collects signals from your brain, which are transmitted to a computer for analysis. The computer monitors your attention level to ensure you are in an optimal state of efficient comprehension. When your attention level decreases, the computer punishes you with high-frequency noise and electricity, and after some time, your brain adjusts itself to avoid punishment.

Lu did not specify the kind of information transmitted by this device, and theoretically, it could be used for any subject. Recalling the iconic scene from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange in which Alex, the juvenile delinquent, undergoes an extreme form of aversion therapy, Lu, like Kubrick, explores the irony of using inhumane means to make the organic mechanical, to create “good citizens” or, in her case, “good students.” In our interview, Lu recalled that her experience in the New Media Art Department (NMAD) was quite different from what her work illustrates. She joined NMAD as an undergraduate when the program was launched in 2003, and later received a full scholarship to pursue a graduate degree in the same program. Lu said that she was a “bad student” in undergrad, in the sense that she skipped classes and did not do well in exams, and when she gets invited for short-term teaching engagements nowadays she is a “bad teacher,” as her knowledge of theory and art history remains “very poor.” She admitted that her strongest attribute as an educator is to find the “worst students” in the class and support them to realize their best work. Lu herself studied with artist-teachers who encouraged her to experiment with her uncommon interests in horror imagery, body modification, and alternative cultures. Lu and her teachers at NMAD, especially the artists Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi, shared an interest in questioning the boundaries of the human body, as well as power, subversion, alienation, and social control. Zhang and Geng began making works around these topics in the early 1990s, many of which are now considered canonical in contemporary art history in China for their forceful criticism of the ideological control and patriotic education promoted by the state.

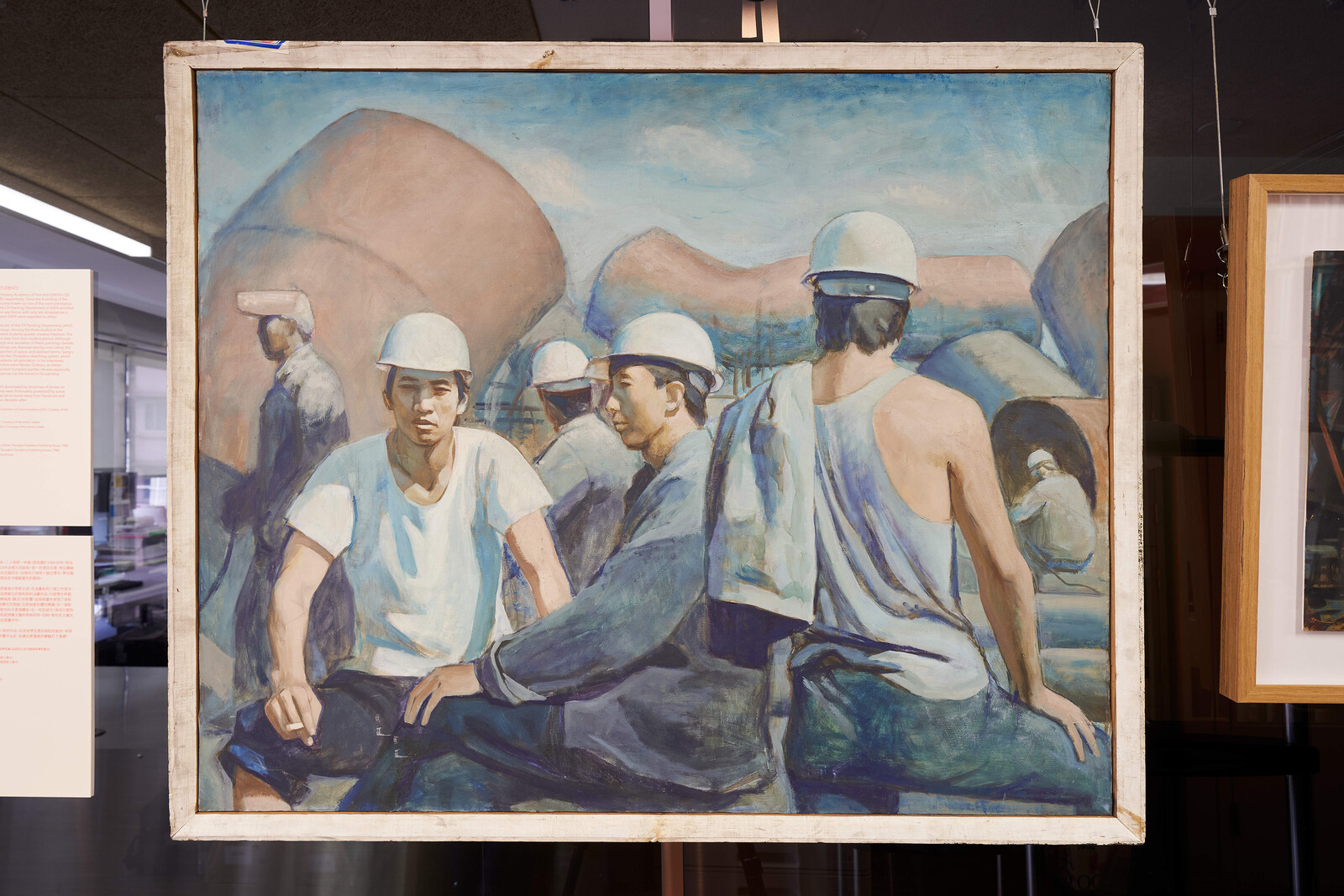

With the exhibition Learning What Can’t Be Taught at Asia Art Archive Library, we set out to discuss the major changes in art education in China from the 1950s to the 2000s through a selection of artworks, archival materials, and interviews. Learning What Can’t Be Taught tells a story about six artists from three generations, who were each other’s teachers and students at China Academy of Art (CAA), the first art academy in the country, established in 1928. Looking at how these artists have learned art in and outside of classrooms, we ask: What makes a “good student” or a “good teacher?” Can artistic attitude be taught or passed down from one generation to another?

Read the full text on School Watch.

School Watch presents critical perspectives on art education. Featured profiles and conversations survey programs in fine art, curating, critical theory, and other related disciplines, as well as the ideas and conditions that influence their practice.