Good Road to Follow

March 1, 2020–January 17, 2021

608 New York Ave

Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081

United States

Hours: Tuesday–Friday 10am–5pm,

Thursday 10am–8pm,

Saturday–Sunday 10am–4pm

T +1 920 458 6144

F +1 920 458 4473

contact@jmkac.org

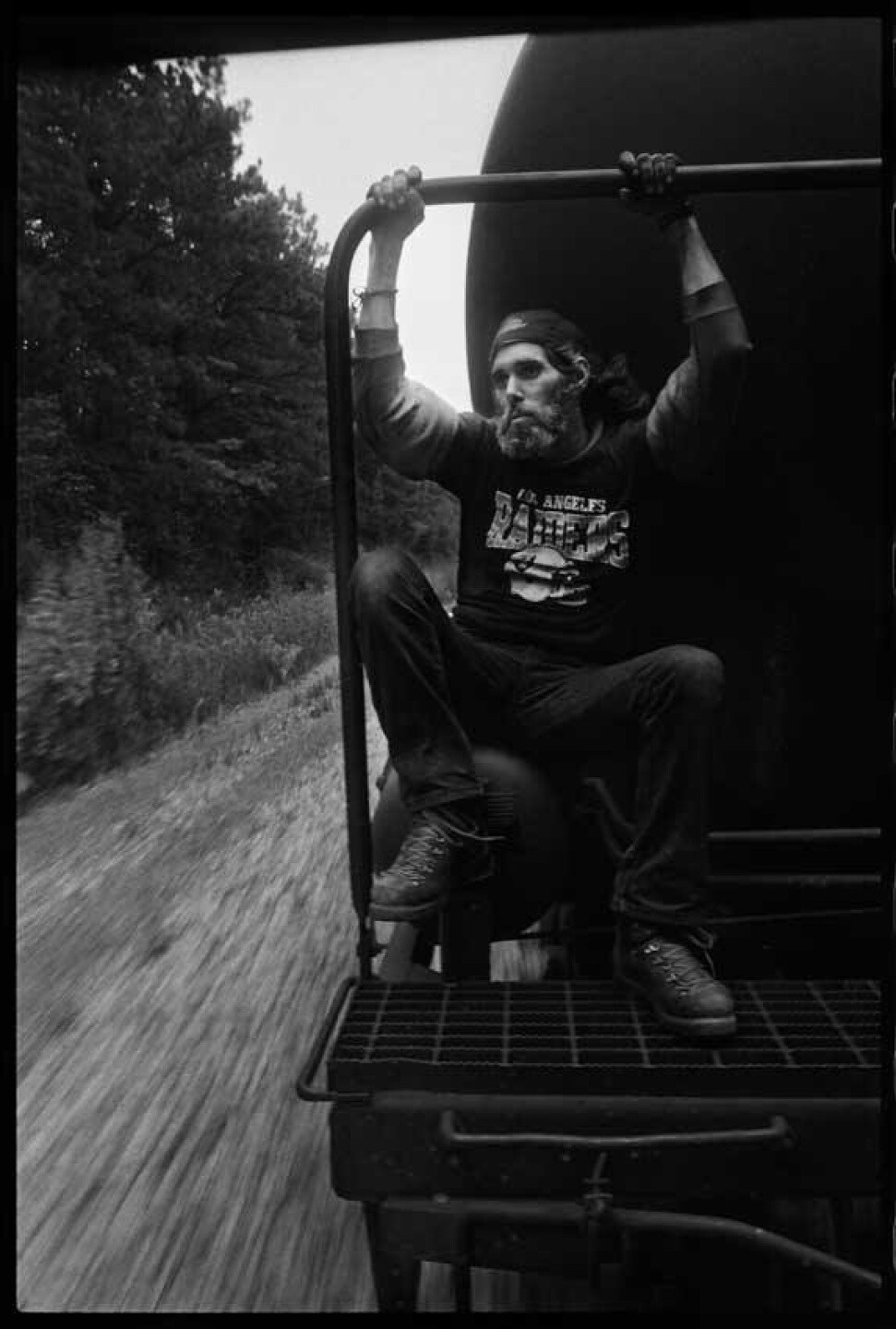

Good Road to Follow examines the work of two artists, separated by decades and experiences, whose work contributes to the lore surrounding American hobos and their lives on the road. Highlighting the important role that artists can play in the documentation and recognition of marginalized groups of people, this exhibition speaks to the power of humankind’s quest for community.

The exhibition, presenting the photographic work of David Eberhardt and the carvings and collection of Adolph Vandertie, is on view at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center through January 17, 2021. While the John Michael Kohler Arts Center is closed, a video tour of the exhibition can be accessed online.

The roaming life of hobos and tramps holds a mythic place in the American imagination. Whether searching for work in the Great Depression, dropping out in the Vietnam War era, or eschewing the traditional idea of home for a transient community, those who travel the country by freight train or hitchhiking have been both romanticized and demonized. Perhaps in that contradiction is the root of the lasting appeal of this way of life.

Adolph Vandertie (1911–2007) was fascinated by the travelers who camped near the railroad tracks in Green Bay, Wisconsin. He mastered the ball-in-a-cage, a basic hobo wood-carving technique that can be modified to produce hundreds of variations. While struggling to make ends meet, Vandertie carved and collected thousands of wood objects that illustrated the hobo and tramp art style. He admired hobos and tramps for their perseverance and what he termed their “deep sense of survival.” His carving habit kept his hands busy and his mind wandering, imagining a life on the rails unfettered by bills and work and guided by a code of ethics shared among honorable people.

To share his collection and knowledge, Vandertie established a museum in his small home. The gallery installation of his collection evokes the spaces that comprised his original house museum.

For nearly two decades, Minnesota-based photographer David Eberhardt lived among a tramp community—jumping trains, dumpster diving, and panhandling. In photographs, he captured his fellow travelers’ demons, wanderlust, search for home on the road, and that “deep sense of survival” so admired by Vandertie.

24 black-and-white images from Eberhardt’s travels are featured in the exhibition. Poignant and intimate, his photographs only hint at what’s beyond the camera’s purview—a life plagued by danger, both from within and without.

Neither of these documentarians provide a complete, or objective, understanding of the hobo culture. But, in their very different efforts and approaches to research, their commitment to witnessing a population of people on the margins remains. In reality, their work may tell us more about them as individuals, and us as viewers, than the hobos and tramps they sought to document.