with Nikolay Smirnov, iLiana Fokianaki, Sam Richardson, Serubiri Moses, Oleksiy Radynski, Mostafa Heddaya and Rijin Sahakian, Luis Camnitzer, and McKenzie Wark

As the novel coronavirus pandemic spreads, we—the people of planet earth—are faced with a dizzying variety of responses: quarantine, containment, vigilant self-quarantine, paranoid self-isolation, and in some cases escape from the above. Suddenly, it is as if circulation itself has turned against us, making healthy freedom of movement in the world a dealer of death. So your flight is cancelled. Your trip is over. We are staying in place for the foreseeable future. Exhibitions, symposia, gatherings of all kinds are postponed. But not sporting events. Those will go on, but without any supporters in the stands. The players will play for empty stadiums and we will watch from home. It’s a good time to catch up on reading.

The movement and circulation of images and words is quite literally what we all do. In the current viral climate, now that mobility is rapidly curtailed and as preparations to be contagious and contained indoors shift between potentiality and reality, certain infrastructures are laid bare in their fragility. At the same time, specific mobilities may revert to how they looked at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The loss of free and near-miraculous movement between needed international gatherings of artists isn’t quite something to be celebrated either. What would it look like to gather and share ideas, works, publications traveling only by data or by foot?

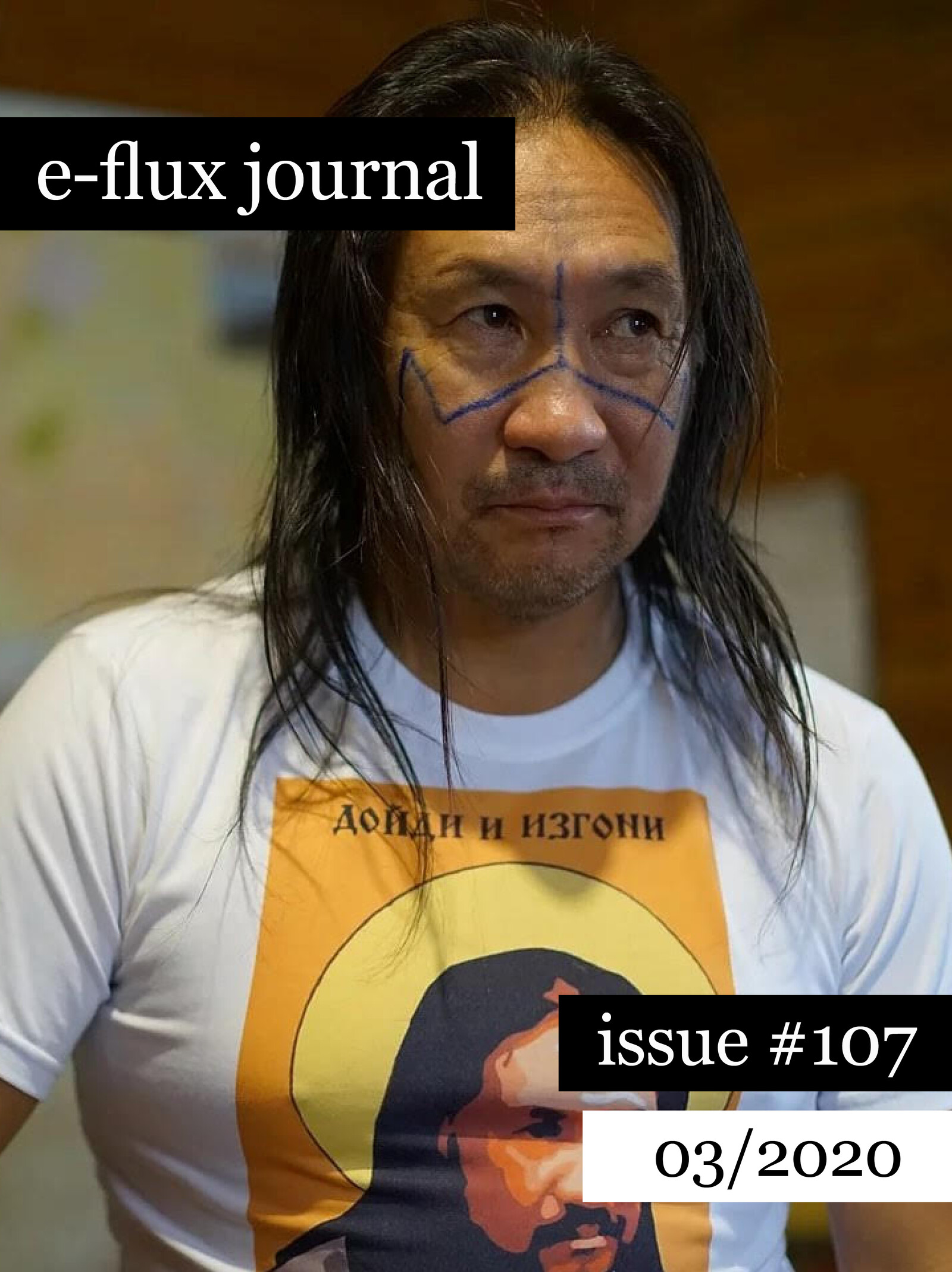

Nikolay Smirnov makes visible a century of religious-based networks across Russia—old believers, shamans, libertarian groups, and spiritual outliers who have operated against or in spite of centralized state power. Smirnov also relays attempts to repress these believers, beginning with populist movements before the October Revolution and continuing to this day, with shaman Aleksandr Gabyshev’s ongoing and much-disrupted march by foot to the Kremlin this year from Yakutia, Siberia, “with a mission to exorcise the ‘powerful demon’ in the Kremlin.” Through examples spanning great distances and time, Smirnov points out that at one point in the mid-nineteenth century at least, such groups could be considered to operate as an “oppositional religious confederate republic” within Russia. Oleksiy Radynski traces the long gas line of twentieth and twenty-first century fossil fuel connections, particularly between the carbon empires of Russia and Germany, in relation to Alexander Bogdanov’s proto-cybernetics to ask: How has information travelled directly through the medium of oil—and now gas—networks?

Sam Richardson enters an ongoing investigation into images and lived experiences of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) through the figure of Saint Wilgefortis, a Catholic female saint known for her beard. Often appearing on the cross as if she were Jesus Christ, throughout history Wilgefortis’s likeness has been removed, considered heretical, and officially purged (1969). But, since her legend arose in the fourteenth century, she has also been venerated as a patron saint by those who are bound as prisoners or held captive by abusive husbands or domestic situations, by survivors of sexual assault, rape, and incest, and as Richardson shows, by people of many genders and identities, including people with PCOS.

Continuing an ongoing essay on narcissistic authoritarian statism, iLiana Fokianaki gives form to the interplay between soft power and hard power by adding additional axes for plotting emergent forms of unaccountable coercion, reminding us of the pressures exerted on cultural workers and institutions when patrons and board members perpetuate the same violence that artists protest against, or when cultural workers respond by retreating into private familism. Serubiri Moses meditates on the cinematic dimension of postcolonial thought, invoking the work of Franz Fanon to ask how violence operates through fantasies and dreams. If colonialism marries legality and structural violence, then Fanon’s practice as a psychoanalyst becomes all the more crucial for uncovering the desires and unconscious fantasies that we might also understand as images and projections.

In “Recolonize This Place,” Mostafa Heddaya and Rijin Sahakian critically untangle the exhibition “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011” at MoMA PS1, and identify how its “belated humanization” through empathetic artists and relativistic curatorial framing extends the “hearts and minds” rhetoric of US occupation. With the billionaire owner of the infamous private military contractor Blackwater chairing PS1 affiliate MoMA’s board, and many canonical European and American artists contemplating the mediatic abstraction of war as spectacle, the experiences of Iraqi artists in the exhibition appear increasingly significant for revealing surprising overlaps between the operating logic of the art institution and that of the US occupation of Iraq.

In “Reality Cabaret: On Juliana Huxtable,” McKenzie Wark writes through and alongside the artist’s music, visual, and written artwork in the form of a remix that’s “also a theory of its own aesthetic methods.” Among other revelations she arrives to: “Maybe it’s about standing in the flow, not where it’s a stagnant pool or a cascading blast, but where it eddies and still trickles. Maybe that stillness is actually propulsion if we think again about what moves relative to what. Maybe there are still times and places that, while not free, at least enable certain bodies and signs a little breathing room. Maybe certain bodies need that more than others, and hence find their way.”

In 1960, at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes in Montevideo, Luis Camnitzer wrote: “I don’t believe that there is any other aesthetic premise than freedom, as much personal as collective.” Continuing into 2020, Camnitzer’s pedagogical and artistic work has developed these premises, including a deep investigation into the interrelation of language and image. At the time, Camnitzer wrote to his fellow travellers, art students and graduates: “Undoubtedly, the most common means of expression is the word. It’s misused and abused. It determines thought rather than being a consequence of it. Metaphors have become formal sentences that have lost their original image, and that is how we think.”

—Editors

Nikolay Smirnov—“Shaman, Schismatic, Necromancer: Religious Libertarians in Russia”

According to the traditionalist mindset, modern repressions have filled the world with troubled spirits. This is why the world has come to resemble a horror movie. Case in point: the vivid emergence of the Yakut horror film in the post-perestroika era, coinciding with a broad return to shamanic beliefs—both expressions of an ethnic renaissance. As the film Setteeh Sir suggests: this land has been stripped of its tradition, as the NKVD has confiscated the shaman’s tambourine. The couple at the center of the film return to their ancestral Yakut village, largely emptied in the years of Sovietization. They face a succession of difficulties, because the place is filled with ancestral spirits enraged at their progeny. Redemption will not come easy: malignant spirits, wrought by human evil and human error, will not simply go away. In a larger sense, horror is people and ideas driven out of society. The ghoulish corpses and dolls are those whom society has destroyed in its civilizing efforts.

iLiana Fokianaki—“Narcissistic Authoritarian Statism, Part 2: Slow/Fast Violence”

In 2004, artist Abdel Karim Khalil organized an exhibition in a small Baghdad neighborhood. It was a group exhibition of artists from the area who felt the need to position themselves against what was occurring in the city. Khalil’s sculptural installation A Man from Abu Ghraib (2004) is a set of realistic marble figures depicting torture: a visual documentation of a historical moment that disrupted and destroyed a society and a people and initiated a new wave of exiles and refugees. It is one of the rare examples of artistic practice that manages to directly confront eso- and exo-violence, in both its slow and fast forms. The work unearths the violence imposed by the Iraqis and the Americans equally in instantaneous bursts of fast violence during the Gulf Wars, but also throughout the interim periods, during the rise of ISIS and through today.

Sam Richardson—“A Saintly Curse: On Gender, Sainthood, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome”

In the latter half of the twentieth century, most of the shrines and likenesses of St. Wilgefortis were destroyed or left to deteriorate after the suppression of her sainthood during the Catholic liturgical purge of 1969. Art historian Ilse E. Friesen, who has done extensive research on the visual representations of Wilgefortis, states that the presence and worship of this saint became identified with anti-Christian, anti-Catholic, and deviant behavior. Her gender presentation was seen as grotesque and a denigration of Christ. Her suppression led to the loss of a saint that offered visibility to survivors of abuse and assault. We must also recognize this loss as a part of the continual erasure of violence against women, trans, and nonbinary people. In contemporary times she has also been interpreted by some as the patron saint of intersex people, asexual people, transgender people, and a powerful lesbian virgin.

Serubiri Moses—“Violent Dreaming”

Unlike Isaac Julien’s 1995 documentary feature film Frantz Fanon: Black Skin, White Mask, which depicted Fanon as a psychiatrist, Olsson’s film remains didactic in its approach to Fanon’s text. However, the film reflects another pragmatic philosophy. When we see women fighters in Mozambique at a typing and copying station they have set up for printing and publishing at a forest camp, it becomes evident that for Olsson, knowledge production is key. One of the characters in this scene conveys to the camera something that had previously been unspoken—that a strategy of colonialism was to disempower the native by denying them education. But, if the right to education is a right to freedom, this line of thinking would diverge from Fanon’s thesis on the freedom and liberation of oppressed Algerians: “What is the true nature of violence? We have seen that it is the true intuition of the colonized masses that their liberation must, and can only, be achieved by force.”

Oleksiy Radynski—“Is Data The New Gas?”

This animation or resuscitation of the gas network wasn’t an outlandish fantasy on the part of the filmmakers. In fact, the plot of Acceleration (1984) was loosely based on the life story of Viktor Glushkov, a pioneering computer scientist tasked with building oil pipeline networks, among other things, after his bold idea of an information network for the USSR was shelved, and his groundbreaking research on socialist artificial intelligence was put on the back burner by authorities. Glushkov was a leading figure in Soviet cybernetic science, a science that he claimed had to be applied to each and every sphere of socialist society. In 1970, top party officials downsized Glushkov’s idea for an overwhelming information-management-and-control network to a series of smaller-scale, disparate network projects. For the better part of the 1970s, he was busy computerizing the Druzhba (Friendship) oil pipeline network that carried Siberian oil into Eastern Europe.

Mostafa Heddaya and Rijin Sahakian—“Recolonize This Place”

Artists in Iraq, particularly young artists who came of age during the invasion, have never lacked the desire or ability to create art. But globally visible contemporary art, as anyone in the field knows, often assumes a ladder of prestigious art-school attendance, production support, mentorship, residencies, international travel, and social skill, usually in English. At Iraq’s two main art schools in Baghdad, which are free of cost, middle- and working-class students hardly have access to resources reserved for elites. Instead of journalists speculating what Iraqi art could have looked like—or curators failing to engage with artists outside their comfort class—it would be more useful to consider how actually-existing forms of production could be supported and understood. Young Iraqi artists never stopped working, and are informed—formally and informally—by the extensive visual and political histories that stretch from the Sumerian era to Baghdad’s current sprawling metropolis. Which “Iraq” is ultimately being recuperated in “Theater of Operations: The Gulf Wars 1991–2011”?

Luis Camnitzer—“Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes”

I don’t believe that there is any other aesthetic premise than freedom, as much personal as collective. As this is also an ethical premise, I don’t believe that one can detach aesthetic premises from pedagogical methodologies. In reference to art, leaving aside any precise definition, I understand that it should be a universal form of expression, since every action should be aesthetic and everything should be creative. The opposite is neutral and stagnant. I understand that there is no “anti-art” but, if anything, there is an “other-art” with the same rights and validity.

McKenzie Wark—“Reality Cabaret: On Juliana Huxtable”

The trans-image is a hard thing to free from this infertile matrix. We trans-es shape ourselves by selecting from presets made in different—and conflicting—discourses, to make the real of the phantasm over into a body-image for the phantasm of the real. This real of nocturnal transmissions is a hard one to live out in the fantastic day that imagines it is all that exists, in which we’re wandering spirits with no country, and always trailing into daylight the attention the cis gaze would rather lavish while itself out of sight.