Live White Slime

February 28–August 23, 2020

Mannerheiminaukio 2

FI-00100 Helsinki

Finland

Centering around the video installation Safe Conduct (2016), Live White Slime at the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, is a kind of purgatory, maybe. A resigned kind of expiation inside of a Sisyphean loop rendered in real and imagined security protocol animations, gratuitously soundtracked by the familiar mechanical wank of Ravel’s Bolero. This is Atkins’ first solo exhibition in Finland.

Making “white slime” involves puréeing or grinding whatever carcass down to glean every last oddment not generally considered “meat.” Once the manual removal of flesh from bone is done, the remainder is forced through a kind of big sieve under significant mechanical pressure. The resulting purée contains bone, bone marrow, skin, nerves, blood vessels, misc. White slime is in those hot dogs, that baloney, the animal feed, etc.

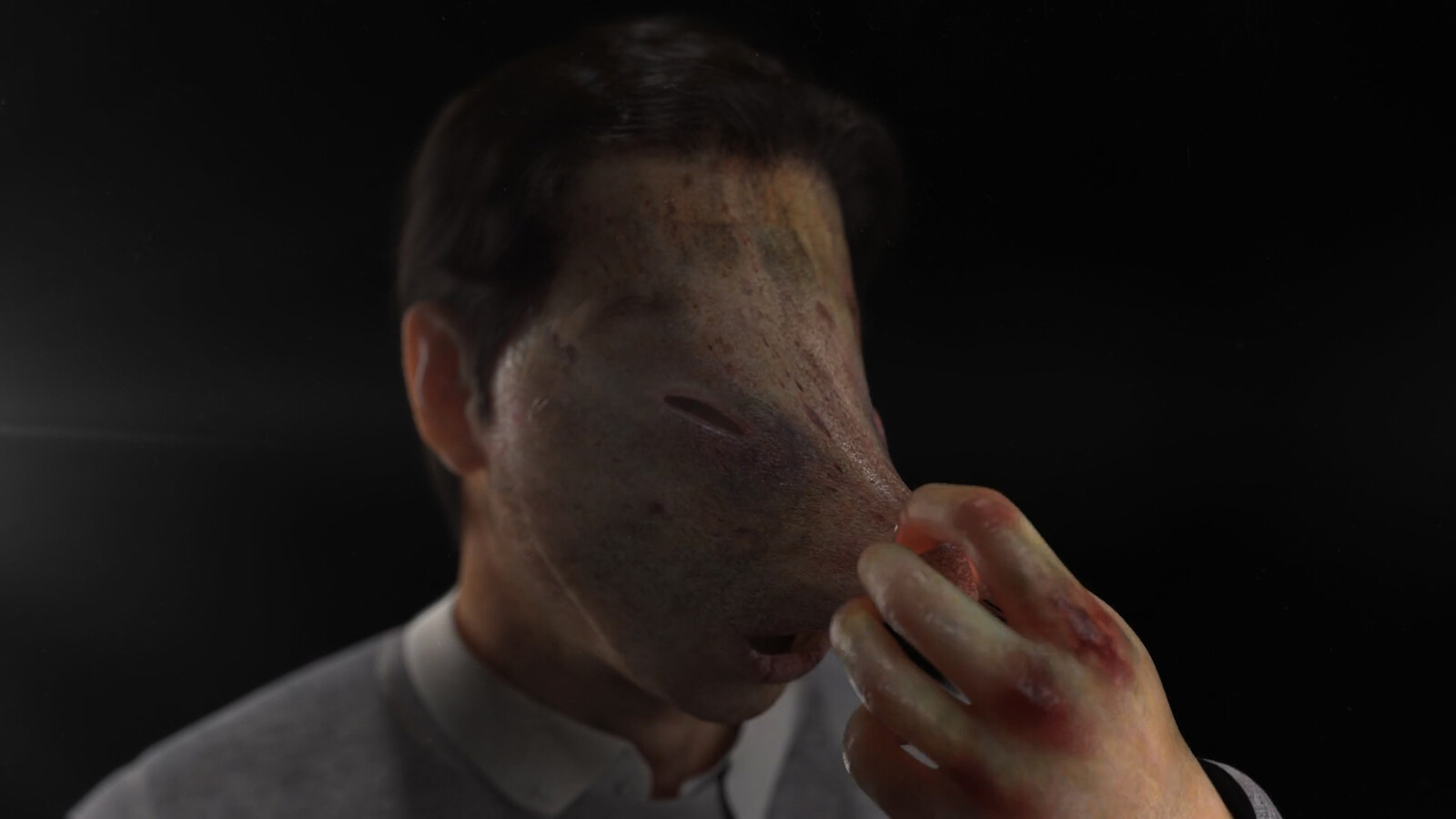

Ed Atkins is known for his uncomfortably intimate, elliptical computer generated animations, drawings, and writing that often feature male figures in the throes of unaccountable psychical crises. These CGI figures seem autofictional surrogates for the artist, possessed and animated by his voice and by his poorly motion-captured body. They are, as one text would have it, “emotional crash-test dummies,” thrust into whatever torturous scenario of digital sentimentality in order to stress-test certain attempts at honesty. Snatches of musical cues, vivid foley and visual effects are employed with abandon, in pursuit of a sufficiency of representation—however awful an idea that sounds. Live White Slime is similarly fraught, if far less interested in sentiment. Instead, like other recent works, Atkins’ spirit is impoverished, hobbled by an encroaching literality. Where there was wizardry, there is now italicized regulation.

Safe Conduct is one of Atkins’ most blunt videos, an earlier presentiment of his current mode. A hellish burlesque of airport security protocol animation spans three large video walls hung from a gantry crane, like an abandoned jumbotron. A computer generated male figure acquiesces to the mores of airport security—placing, for example, his pineapple, his kidneys and his severed head in the tray—along with a laptop, a pistol and countless boxcutter knives. Edits serve as choreography in this appalling dance, set to the eternally debased, stock music of Maurice Ravel’s Bolero.

Perseveration, an Alzheimer’s symptom, is the obsession with repeating words or actions. It’s compulsive respite, both to Maurice Ravel’s deteriorating mental health when he wrote the Bolero—and more generally to various psychical traumas visited upon the subject under late-capitalist, neoliberal hegemony. It’s a kind of dehumanizing incorporation, albeit one that comforts by impersonation: Ravel spoke of the Bolero as a “machine for orchestra,” and his efforts to annul the expressivity of the orchestra with the Bolero’s incessancy are at least analogous to the automation of movement, of the heavens, the martyring of dignity, the presumption and arrogance of privilege.

Perseveration means a repetition that disguises deterioration by inattention’s drift, maybe. Even as entropy remains inevitable. Opiating, per Marx, is primarily ideological grift. Safe Conduct is silly. Airport security animations are white lies, neotenic in their pacification. The figure wears a London 2012 Olympics sweatshirt like soiled vestments. The work’s intellectual acquiescence precedes the figures physical one.

Ninth Freedom (2020 onwards) works backwards from Safe Conduct: Atkins has taken real-world, in-flight safety animations of the type Safe Conduct pastiches, and added a graphic, foley soundtrack. Sound, uniquely, describes bodies: vibrating—animating—matter into a commotion to mirror that of the source of the sound. Earlier works of Atkins’ understood foley sound to be the thing that lends heft to weightless his computer generated imagery. Here, the new soundtracks summon matter and return a kind of palpable reality to the in-flight videos—albeit exaggeratedly: a necessity to compensate for the imagery’s original design as palliative, lite representation of preparation for a catastrophic event. Where silence afforded a kind of unreality, sound grounds and mocks with bathos in the videos. Adding sound is necromantic. A body feigns inanimacy (plays dead) in order to maybe just about endure forcible animation.

The acoustic panels that flank the video works muffle the space, dissembling it phenomenologically. The hangar-like space is attempted shrunk to something more intimate, cinema-like. Or otherwise spaceless: a no-place the obverse of the white cube and its sanctifying of art; the acoustic panels meant to situate the videos inside themselves, apart from reality. This practical purpose is partly unravelled by the texts and diagrams embroidered on them. Rather than receding into invisible grift, the panels become points of attention, information, the reflexive content serving both to reveal the acoustic treatment, and metaphorise their purpose and convolute the subject of the videos: A list of Isaac Newton’s adolescent sins, a scale comparison of dinosaurs and airliners, a list of “squalid” things, an alphabet of demons, among others. The language of administration and information abuts mysticism and poetry.

*Airports and the heavens they gate are rendered and rendered down, dully familiar, an inconvenience, a nightmare of figured horrors. Security protocol is a choreographed indignity to maintain safety. Necessary, we understand. Borders are bores for the privileged, and guillotines or cliffs to everyone else.

Live White Slime loops, then—a perseverant limbo.