Ten Drawings for Projection

June 3–September 1, 2019

In 2015, the South African artist William Kentridge gifted 10 Drawings for Projection (1989–2011) to Eye Filmmuseum. These ten short animated films—made over a period of more than 20 years—are intimate, personal meditations by Kentridge that resonate with the recent turbulent history of South Africa. The films marked Kentridge’s breakthrough in the international art world as an engaged artist with a sense of commitment and concern for the developments in his native country. “I have never tried to make illustrations of apartheid, but the drawings and films are certainly spawned by and feed off the brutalized society left in its wake,” he once stated. “I am interested in a political art, that is to say, an art of ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures, and uncertain endings.”

The ten works go on show as a complete series this summer for the first time in a museum. Also included in the presentation are eight tapestries as well as the installation O Sentimental Machine (2015), for which Kentridge selected material from the rich collection of Eye Filmmuseum.

An important and recurrent theme in Kentridge’s work is the fraught history of his native South Africa. Perhaps not surprisingly for the son of two leading anti-apartheid lawyers, Kentridge succeeds in capturing this conflict, this past, in all its complexity. His art is not an activist pamphlet about evils and crimes, but a personal story in which evils and crimes are linked to the complexity of existence, to uncertainty, and to broader reflections on the human condition.

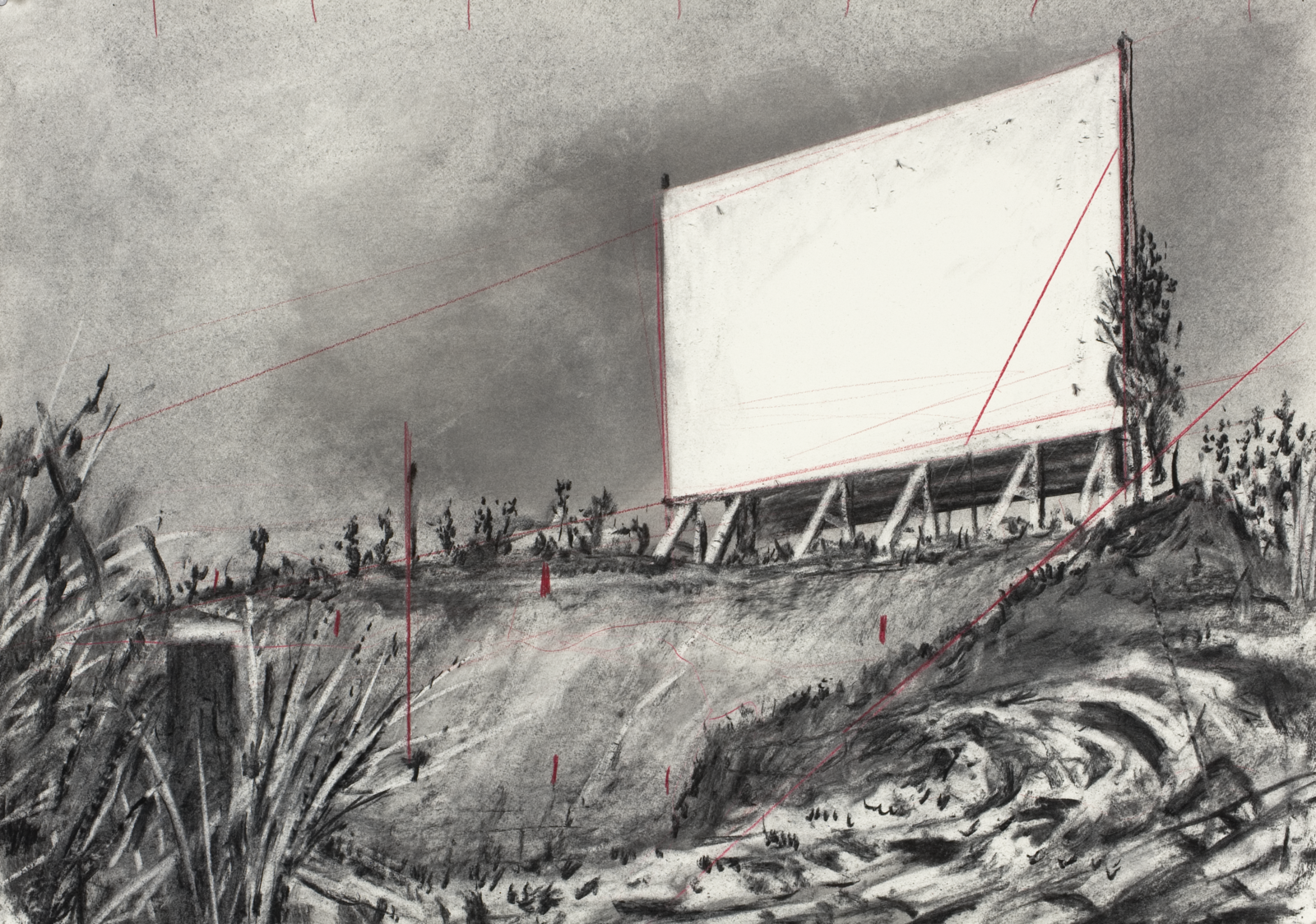

The distinctive animation technique used by Kentridge, in which he draws, erases and redraws parts of his charcoal sketches over and over, allows traces of the past to remain visible in the present. This technique also reveals the importance of remembering—and forgetting—in the work of Kentridge.

In Ten Drawings for Projection—including films such as Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City After Paris (1989), Felix in Exile (1994), History of the Main Complaint (1996) and Other Faces (2011)—Kentridge introduces two characters. Soho Eckstein, a rich industrialist, and property developer in Johannesburg, and Felix Teitlebaum, his opposite, a quiet dreamer of a man who reflects on life, and questions what is happening in the world. Both characters seem to be derived from one and the same individual. In Kentridge’s films, they are not fixed identities but change constantly. Over the course of the series, the two characters increasingly come to resemble each other, and the artist “uses” them to explore his own humane view of the human condition, one that centers not on any single truth but on doubt, uncertainty, and openness to change.

O Sentimental Machine (2015), made by Kentridge at the invitation of the 14th Istanbul Biennial, contains a number of remarkable pieces of archival film that Kentridge discovered in the collection at Eye. The work, which is based on the period that the Russian revolutionist Leon Trotsky spent in exile on a small island off the coast of Istanbul, shows the fictitious office of Trotsky. Using five projections, Kentridge shows not only images of Trotsky and his revolution, but also his own vision of failed utopias. An important element is the recording of a speech that Trotsky wanted to deliver in Paris. That plan came unstuck when the Turkish authorities refused to allow him to travel, so he decided to record his speech on film instead and present it in Paris is this way. But the film never reached Paris and was mislaid. The installation also includes footage of Bolshevik marches, the corpse of Lenin and the quays of the Bosporus. Drawing on the visual language of early cinema, of Dada and of the Marx Brothers, Kentridge brings this history to life and invites reflection.

Kentridge made the eight huge tapestries with the help of a local tapestry studio in Johannesburg. They are populated by dark silhouettes, directly recognizable from Kentridge’s work, against a backdrop of maps. We see iconic images of porters, refugees, pilgrims, and demonstrators, as well as characters from his opera adaptation of The Nose by Dimitri Shostakovich. Kentridge: “I like the fact that tapestry is like a frozen projection, a portable mural that you can roll up and carry to your next palace.”

Curated by Jaap Guldemond, in collaboration with Marente Bloemheuvel