Luca Frei

Hermann Scherchen: alles hörbar machen II

December 1, 2015–January 30, 2016

Opening: Saturday November 28, 4–8pm

Barbara Wien

gallery & art bookshop

Schöneberger Ufer 65 (3rd floor)

10785 Berlin

Hours: Tuesday–Friday 1–6pm,

Saturday noon–6pm

T +49 30 28 38 53 52

F +49 30 28 38 53 50

bw [at] barbarawien.de

Scherchen was one of the few people that naturally lived in the new—a necessary novelty for the expansion of his vitality at the expense of his overflow of energy. He never denied his reputation; I can describe him as a cautious proselyte, a solemn instigator, a spirit that was as adventurous as patriarchal. Can we apply, like Gide did for Claudel, this somewhat cruel yet powerful image of a “solidified cyclone”? (1)

In the portraits, assembled by Maurice Fleuret for Le Nouvel Observateur immediately following Hermann Scherchen’s death, Pierre Boulez borrows a relevant oxymoron to decipher and render the complex and unstable character of the German musician and conductor. In the term “cyclone,” we find the idea of a formidable chaos circling a calm center. Indeed, Scherchen’s biography (1891–1966) suggests an intense and troubled period, inhabited by a farandole of significant figures, searching to comprehend the history of music in a very broad spectrum (for instance, music under specific political ideologies, modern and experimental music, music and the technologies of recording and sound transmission, etc.).

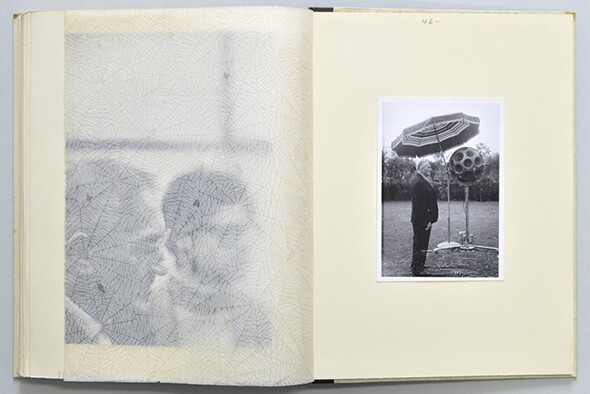

With the exhibition Hermann Scherchen: alles hörbar machen II at Galerie Barbara Wien, the Swiss artist Luca Frei (based in Malmö) dedicates his second solo show to Hermann Scherchen and his late musical research in Gravesano, Switzerland. We find Frei juggling several hats in this project: visual artist, researcher, archivist, and grandson of Hermann Scherchen. In a sculptural installation, he reacts to the architectural interventions of Hermann Scherchen and his acoustic experiments, whilst a photo edition titled Gravesano Album provides an insight into the social and musical events that took place in the building and garden of Gravesano.

The first chapter of Frei’s interest in Scherchen was an exhibition in Studio Dabbeni in Lugano (2), located 8km from Gravesano, the village where Scherchen spent the end of his life. Berlin, as the setting of the second chapter, is also a highly symbolic location. Indeed, the conductor was born in the German capital, where he began his career as a violinist; he played in several orchestras, including the Berlin Philharmonic, until 1933, when he left in protest against the Nazi regime.

At a young age, he recognized that he would never be a virtuoso musician and decided to become a conductor. His overwhelmingly intense creative life would begin in 1914. Here is an attempted overview: Frei conducted, amongst others, orchestras in Riga, Frankfurt am Main, Leipzig and Winterthur; he founded the journal Melos in 1920, publishing a seminal essay on conducting, “Lehrbuch des Dirigierens” (1929), and later created his own publishing house, Ars Viva, in 1950. In 1919, he constituted the Neue Musikgesellschaft; he put on the orchestra Musica Viva in 1936 in Vienna, organized workshops and conferences on modern music throughout Europe from 1933 onwards, and led the Studio Orchestra at the Swiss radio until 1950.

1950 was a crucial, if somewhat disastrous year for Scherchen in understanding the ultimate and most significant of his projects: the Gravesano Electro-Acoustic Studio. Scherchen conducted at the Prague Spring Festival of this year. Following this performance, he was accused of supporting the Communist ideology and regime. Throughout his career, music was for Scherchen a tool to educate and open minds, one that moved beyond political attitudes and alliances. Despite his declarations, however, a veritable scandal surrounded him. He was fired from his role at the Swiss radio and lost his position as a conductor in Winterthur and Zurich. Also in 1950, his wife, Xiao Shuxian left him and went back to China with their children. The same year, Scherchen’s mother died.

In 1954, Scherchen and his new wife Pia Andronescu found themselves a 12-room property in Gravesano, a village of only 200 inhabitants. Almost four years after such dramatic events, the house appeared to be an ideal refuge. Here, the concept of “neutrality” reigned on multiple levels: politically (supported by UNESCO, the site was beyond any nationality), artistically (outside of any ancient/modern, electronic/concrete music quarrels), and even acoustically. Indeed, the conductor used his home to reach an architectural ideal for sound play, recording and transmission. He wrote, “I would like to have a space that I can deactivate” (3). Thus, Scherchen surrounded himself with architect Hoeschle to conceive three studios with as many different architectures and functions. For Scherchen, the studio constituted an ideal: a highly malleable space, compared to the rigid orchestral stage. It is a technological tool, which frees music from its accessories: “through the microphone, music is for the first time presented as itself” (4). In this capsule, emptied of disturbances, everything can be heard and made audible.

Gravesano studio was also a residency for musicians, sound engineers and many different kinds of practitioners. International and interdisciplinary symposiums were organized there, making it a rite of passage for sound experimenters. Xenakis portrayed it as a “fertile garden where it felt good to blossom” (5). The journal Gravesaner Blätter reported on this effervescence until 1966, including cross-disciplinary writings by authors such as Theodor W. Adorno, Pierre Schaeffer, and even Le Corbusier.

The studios were dismantled soon after their founder’s death in 1966. How, then, to present or make present a space and its context that no longer exists? Frei, opting out of dioramas, rather tackles the exhibition space by mixing his own work with accurate archival documentation. In a separate room, Frei offers an installation that reproduces the main studio floor plan in form of a sculptural platform. The different units are movable in numerous combinations, mimicking the malleability of the studio. For the second exhibit of this project, the dialogue between Frei’s own work and the archive is more vivid. Here, the artist takes up a delicate position as “artist-archivist,” at once a true archive producer, and developing aesthetic forms using his own vocabulary fed by this research. This association allows Frei to escape from storytelling strategies, which would have, in a way, fed the mythical character. Indeed, Frei speaks through the collections he produced and assembled himself, constituting his own work through the archive of another. These different voices can freely coexist in the artist’s production. Displacing research on Gravesano in a visual art exhibition is perhaps the optimum way to express the vigorous eclecticism that existed in this micro-cosmos of a late polymath.

Text by Gauthier Lesturgie

(1) Pierre Boulez, Maurice Fleuret, ”Scherchen : un cyclone figé”, Le Nouvel Observateur, June 22, 1966.

(2) ”Hermann Scherchen : alles hörbar machen I”, Studio Dabbeni, Lugano, 19.9–7.11.2015.

(3) Hermann Scherchen: Aus meinem Leben Rußland in jenen Jahren. Erinnerungen, Berlin 1984, S.62.

(4) ”Durch das Mikrophon ist die Musik zum Erstenmal auf sich selbst gestellt.” Hermann Scherchen, ”Bekenntnis zum Radio”, unpublished manuscript, Bern August 9, 1944 (HSCHA 17/74/692). Cited in Dennis C. Hutchison, ”Performance, Technology, and Politics : Hermann Scherchen’s Aesthetics of Modern Music,” Dissertation, The Florida State University School of Music, 2003.

(5) Iannis Xenakis, Maurice Fleuret, op. cit.

Luca Frei (b. 1976, Lugano, Switzerland) lives and works in Malmö, Sweden.