September 15–November 13, 2016

Vanderborght

Rue de l’Ecuyer 50

1000 Brussels

Belgium

Cinéma Galeries

Galerie de la Reine

26 Koninginnegalerij

1000 Brussels

Belgium

Curated by Barbara Rose

Under the High Patronage of Her Majesty the Queen of the Belgians

Roberto Polo Gallery, in collaboration with the City of Brussels and Cinéma Galeries presents Painting After Postmodernism I Belgium – USA, curated by Barbara Rose. The exhibition, comprising 256 paintings in 16 solo shows of eight American and eight Belgian prominent artists, as well as its accompanying catalogue published by Lannoo, is devoted to defining new modes of painting that reconstitute, rather than deconstruct the elements of painting in fresh new syntheses free of dogma and theoretical reduction.

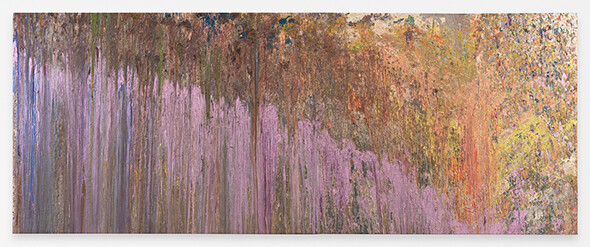

Painting After Postmodernism I Belgium – USA takes place in the historic Vanderborght building and Cinéma Galeries’ exhibition space, The Underground. The USA is represented by Walter Darby Bannard, Karen Gunderson, Martin Kline, Melissa Kretschmer, Lois Lane, Paul Manes, Ed Moses and Larry Poons; Belgium by Mil Ceulemans, Joris Ghekiere, Bernard Gilbert, Marc Maet, Werner Mannaers, Xavier Noiret-Thomé, Bart Vandevijvere and Jan Vanriet.

In conjunction with the exhibition, Cinéma Galeries presents a series of films on painting (several by Barbara Rose) chosen by Dominique Païni, film historian and former Director of the Cinémathèque française, the Centre national d’art et de culture Georges-Pompidou and the Fondation Maeght.

Painting after Postmodernism I Belgium – USA investigates why when Marcel Duchamp declared that painting was dead in 1918, many believed him. However, he was wrong. As it turned out in the decades before and after World War II, Picasso, Matisse, Miró and the New York School continued to make monumental mural scale paintings on the level of the greatest art of the past. In the politically radical 1960s and 1970s, it once again became fashionable to toll the death knell for painting, perceived as a product of bourgeois culture. In its place, galleries and museums defined the avant-garde as conceptual art, video, mixed media and installations, all of which denied painting its position of preeminence. Instead, painting was to be reduced to just another form of postmodernist endeavour.

Such demotion was perhaps the inevitable result of depriving painting of the fullness of experience that it once offered and reducing it to a pure “optical” experience devoid of content, metaphor or surface. The dominant art critic of the post-World War II era, Clement Greenberg, insisted that painting in order to remain “pure” had to be addressed to eyesight alone, because he argued that the essence of visual experience was “opticality.” All traces of the hand were to be expunged in favour of an instantaneous retinal impact.

Greenberg’s essays “Modernist Painting” and “Post-Painterly Abstraction” became canonical in their definition of high art as reduced to its exclusively optical essence. The material properties, not of pigment as physical matter, but of the canvas as cloth, were to be stressed at the expense of any tactile effects; moreover, painting had to be exclusively abstract, freed of any figurative or even metaphorical content.

Beginning in the 1980s, Greenberg’s dogma was challenged by European critics, such as Achille Bonito Oliva, who used the term postmodernism to describe painting that mixed historical styles in pastiche formulations that were mainly figurative. In 1984, Peter Burger defined postmodernism as “the end of the historical avant-garde movements.” Frederick Jameson characterised postmodernism as a breakdown of the distinction between “high” and “low” culture, subsuming the kitsch imagery of mass culture in quotations and reproductions recycled in painting.

Postmodernism deprived painting of originality and first-hand experience at the same time that Greenberg’s disembodied abstraction, addressed to eyesight alone, collided with the desire on the part of some artists to retain the wholeness of the aesthetic experience made available by the old masters in their fusion of the haptic quality of sensuous painterly surfaces with the optical melding of colour and light. The artists represented in this exhibition wish to restore tactility to painting, to redefine drawing as part of the pictorial and to go beyond postmodernism to retrieve the fullness of painting as major art, including its tactility, explicitly material surface and capacity for metaphor as well its purpose to fulfil what Henri Bergson defined as its principle function: to be “life enhancing” in its vitality.