The Opening Up of the World

September 30–December 3, 2017

Lunds konsthall is proud to present Simryn Gill’s first institutional solo presentation in a northern European country. Its title is also the title of a textbook in political economy from 1936 by J. F. Horrabin, a Marxist geographer well known in his time. Gill keeps multiple copies of it in her library at Port Dickson, Malaysia.

Gill is a Malaysian national of Indian ancestry, who represented Australia at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013 and participated in two consecutive Documentas, in 2007 and 2012. Much like her social self, her work takes pain to stay gentle and decorous as long as possible, because the calm this approach helps establish is a necessary condition for making informed and instructive observations about the world—prying it open, as it were.

Yet such straightforwardness is always conditional on how much understanding viewers show, how far they are willing to open up to the work and to the world that it creates and reveals. So the exhibition at Lunds konsthall—containing photographs, prints, other works on paper and three-dimensional objects from the last decade—is both visually inviting and conceptually demanding.

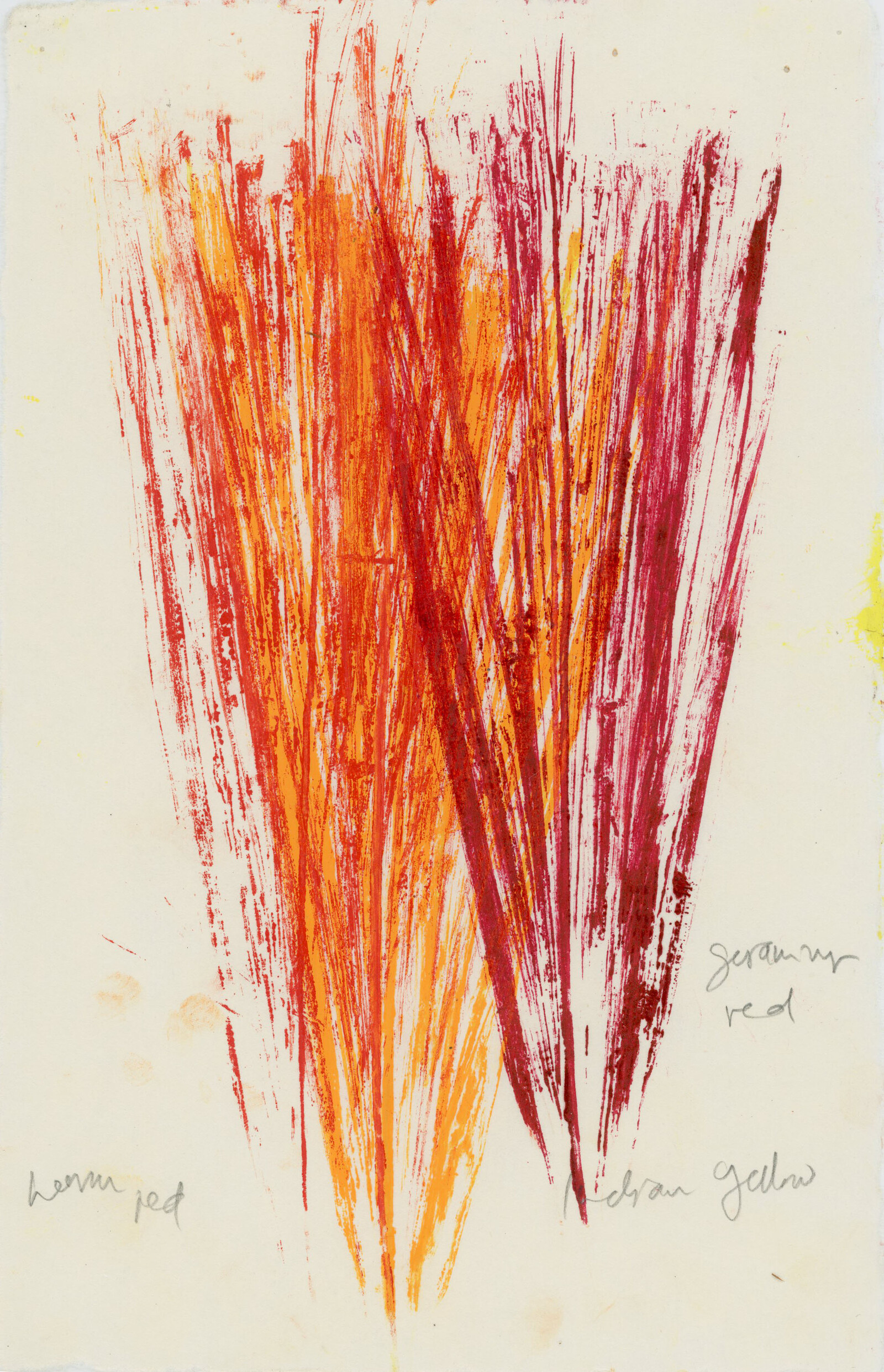

If we were looking for an overall metaphor to describe The Opening Up of the World we might say, somewhat reductively, that it articulates the experience of mapping and the mapping of experience. One concern that unites the works on display is that of record-taking, understood both figuratively, as the imprint that the world makes on the artist and that she conveys to us through her work, and literally, as when she makes prints directly from sprouting coconuts or run-over snakes in the two new series “Travelling Light” and “Naga Doodles” (both 2017) that are now premiering at Lunds konsthall.

Much like these exercises in direct printmaking, the large black-and-white photograph Scale, or Tasha and the Tree (2005/14) combines record-taking and measure-taking by letting Tasha, a young girl from Port Dickson, pose under a giant tree at the city’s old cemetery. The untitled sheets of paper, partially eaten by insects, can also be seen as records: of how bugs bore through books and of how, as Gill says, “there cannot be sentimentality toward paper in the Tropics.”

This exhibition is—and again both figuratively and literally—bathed in light: not least the physical light streaming through the three series of photographs taken in an unsold compound of mock-Tudor weekend homes in Port Dickson: “My Own Private Angkor” (2007–09), “Wormholes” (2009) and “Windows” (2011/17). Gill repeatedly snuck into the abandoned spaces, inexorably decaying after local “entrepreneurs” removed all metal armatures they could sell for scrap, including the aluminum window-frames.

The exhibition is also about color. There are the flaming red and yellow sprouts of “Travelling Light” and the occasional stains of dried snake blood in “Naga Doodles.” There are the hundreds of potato prints, made with luxury fountain-pen ink in many different nuances, of “Let Them Eat Potatoes” (2014). There are the reddish and grayish objects of “Domino Theory” (2015): bricks whittled down to egg- or bread-like shapes by the ocean, cubes shaped by Gill from soil she dug up close to termite mounds. And there are colour photographs, not only in “Windows” but also in the series “Social Insects” (2012/16) and “Sun Pictures” (2013).

Lunds konsthall warmly thanks Simryn Gill for her extraordinarily precise and appealing exhibition, and also the guest curator Anders Kreuger. For their collaboration on this project, Lunds konsthall thanks M HKA, the Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp, and the galleries representing Gill: Tracy Williams Ltd in New York, Utopia Art in Sydney and Jhaveri Contemporary in Mumbai.