June 23–August 27, 2017

Centre d’art contemporain

Avenue Conti

58320 Pougues-les-Eaux

France

Hours: Wednesday–Sunday 2–6pm

T +33 3 86 90 96 60

clement.guignard@parcsaintleger.fr

Alice Aycock, Julian charrière, Toril Johannessen, Zdenek Košek, Katie Paterson, Marie Velardi, Remy Zaugg

Events:

Writting workshop: workshop led by Pierre Bastide; free expression about artworks of the exhibition

Conversations: June 25, 4pm, with Jennifer Fréville, artist

Conversations: July 2, 3pm, at Parc Saint Léger

Family workshop: July 23, 3pm, visit the exhibition and workshop

Forum Biosphere: July 24–28, workshop leaded by Perrine Forest, Elise Legal, Mona Chancogne, Valentin Rolovic, Guillaume Seyller

Conversations: August 6, 4pm, at Parc Saint Léger

Conversations: August 27, 4pm, with Wilfrid Séjeau, bookseller and environmentalist

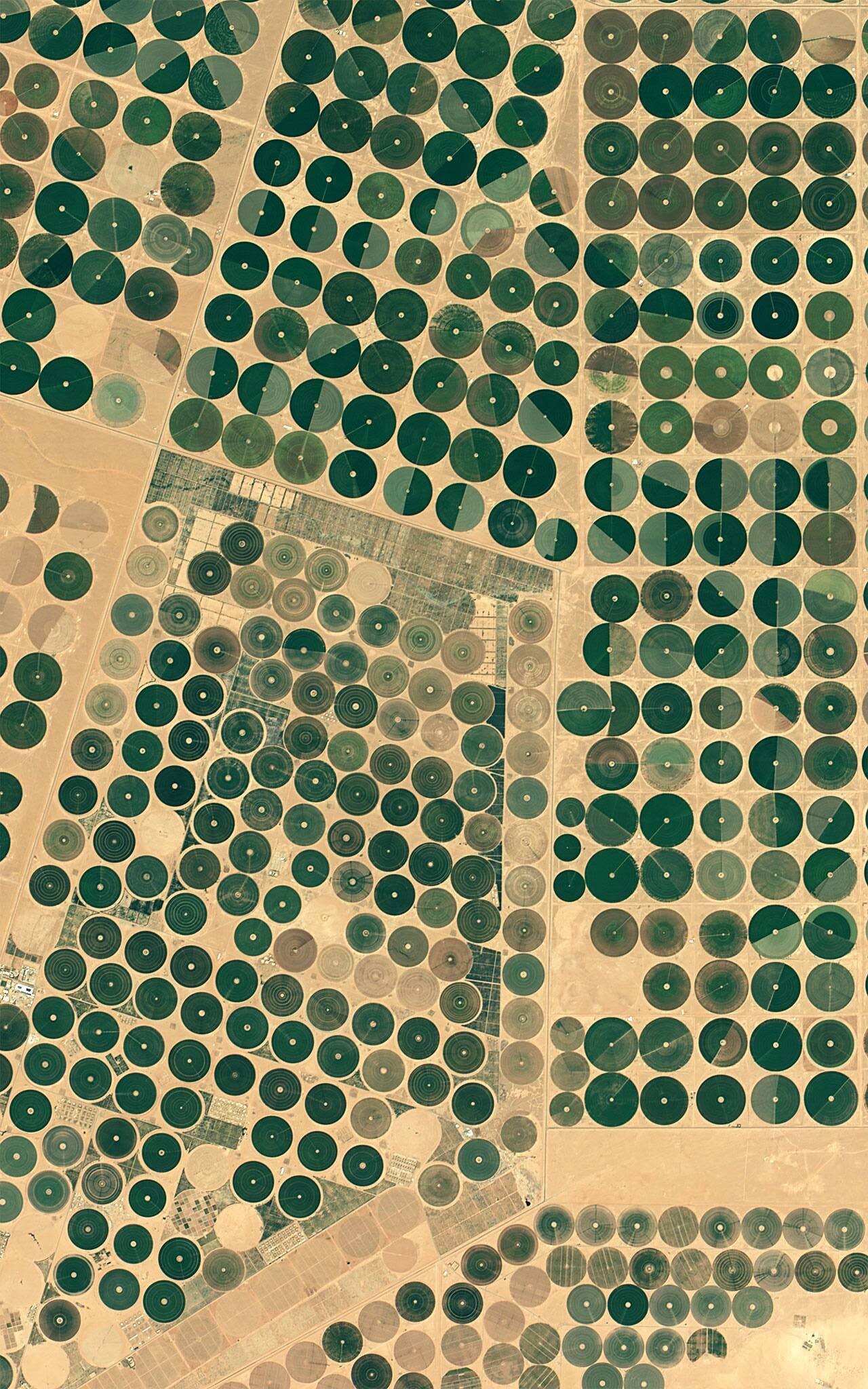

The artworks brought together for the exhibition Paysage Anthropique (Anthropic Landscape) makes plain the attention artists have been paying to contemporary environmental questions, although perhaps the featured pieces are more immediately concerned with taking stock of the impact human activity has had on the transformation of our surroundings. The title both quotes and consciously distorts another, earlier exhibition title, that of the Robert Smithson show called A Retrospective: the Entropic Landscape, 1960-1973. The artistic practice of this key figure of contemporary art offers a direct echo more or less of most of the works shown in Paysage Anthropique. Smithson’s influence is especially important for his contribution to opening up the field of sculpture in the 1970s to nature and the site-specific work of art, but especially for making entropy an artistic process. By introducing this concept borrowed from thermodynamics, a function that enables one to quantitatively measure the deterioration of a closed system in terms of its disorder, Smithson underscored above all the effects time has on human constructions. For the artist, time manages to eventually have the upper hand with respect to any structure, reducing it to a state of ruin. Thus it highlights some kind of natural violence, which indeed contributes to destroy human’s works and humanity itself, leaving behind mere rubble. And yet nature, too, can be the victim of disorder and become a ruin in turn.

All of the works on display deal with landscapes, nature, and a connection with time, either as an objectivized, institutionalized, or aestheticized fact, or as a support for a range of futuristic speculations. While the art practices enjoy a strong connection with our natural surroundings, they emphasize less nature’s supposed power than the impact human activity has on environmental transformations. They seem to be taking note then of a new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, in which human influence is having the same impact on the natural world that rivers, floods and erosion do. Its originality lies in the fact that this geological epoch conveys a future, unlike the other ages that geologists have defined long after their end. The Anthropocene is our present, is determining our future, and the future is becoming intrinsic to the definition of our geological past, with an endless crisscrossing of chronological lines. The featured works play with that contrast between the short time of human action and the long time of geology, making projection in time a means to link past, present, and future. In this situation, humanity is but one element of an ecosystem that is constantly evolving, and the state of the Earth is a memory of the future.